Everybody loves nature – or at least the idea of it. But what, exactly, are we talking about when we talk about nature? Is it the great outdoors or even your local park? Perhaps nature is a concept, a way to think about what exists.

◊

Ah, nature. The great outdoors. Woodland, desert, mountain, and aquatic creatures going about their lives. Take a deep breath of fresh, fragrant air, so crisp and clean, so…wholesome…natural. All over the world, arid deserts, snowy mountains, and ocean parks are devoted to the preservation of nature for our enjoyment and that of generations to come.

But hang on. Do these public spaces tell us where nature begins and ends? Is nature restricted to the cartographer’s tools? Can you find nature in your backyard or apartment terrace? Just what is nature, anyway?

Maybe it’s not a location, but a concept. More specifically, perhaps it’s a concept that is understood by contrast with what’s artificial. Tools, buildings, plastic bags, and art are artificial, while trees, rocks, fish, and birds are natural – the former are made by humans, the latter are not.

OK, so “nature” means everything that’s not made by humans. So far so good, but what is “everything”? Another way to ask the question is this: What exists and how did it get that way?

For more on Mother Nature's effects on the human mind and body, check out The Nature Effect on MagellanTV.

Let’s start with change or motion. When we think about nature, we think about seasons, ecosystems, and other cycles, such as ocean tides. We think about individual things coming to be, like a frog comes to be from a tadpole, or an oak tree comes to be from an acorn. How, historically, have we accounted for such observations? How have we explained them?

Nature is the Balance of Opposites, Cycles, and Change

In cultural traditions around the world – from the ancient Egyptians to the Norse, from the Maya to the Hopi, or from the Maori to the Fon – divine powers created and shaped what there is and how various civilizations thought about the world. Gradually – and also globally – people began turning to observation for explanations of things like earthquakes and weather, rather than supernatural forces.

So, for example, whereas in the Homeric era explained ocean storms in terms of Poseidon’s power, subsequent ancient Greek thinkers such as Thales, who was active from the end of the seventh century BCE and into the middle of the sixth, thought of water as the original material from which all things come, and into which all things resolve. Water is, after all, essential for life, and there is good evidence that life began in water.

Twentieth century psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers coined the term Axial Age, which refers to that period – roughly 900–300 BCE – during which people around the globe developed the religious and intellectual systems that form the origins of much of today’s beliefs about the universe and our place in it.

In the sixth century BCE, in what is now Turkey, Heraclitus of Ephesus is said to have produced a single work on cosmology, theology, and ethics – all of which, for Heraclitus, are intimately connected. In the surviving fragments and testimonials, nature emerges as a unity of opposites and change. Consider, for example, that fish breathe underwater but humans can’t, and so “Sea is the purest and most polluted water”; night and day alternate; hot is the opposite of cold and wet the opposite of dry. Opposites, Heraclitus thought, generate balance, and motion creates stability. “Changing, it rests,” he tells us. Fire, for example, depends on change for its existence, yet we think of it as a single thing. Or consider the way that motion holds together otherwise disparate elements as a unified whole, which occurs when multiple voices sing different notes yet create a harmony.

.jpg)

(Credit: Robert Anders, via Wikimedia Commons)

Guiding the change, according to Heraclitus, is a rational principle, which he calls logos. Among the Greek term’s myriad meanings is “word,” “reason,” and “account.” So, while nature is in continual flux, it is not chaotic but lawlike. “Listening not to me but to the logos, it is wise to agree that all things are one.”

Heraclitus is sometimes called The Riddler for oracular pronouncements like this one: “The road up and the road down are one and the same.”

During roughly the same time that Heraclitus was thinking about the logos, Lao-Tzu developed the notion of the Tao (Dao) in what is now China. In the surviving fragments of Tao Te Ching, Tao is both the harmony underlying opposites and that cosmic principle constituting reality, “pervading all things without limit." The universe is, accordingly, dynamic but orderly.

Nature Says Everything Seeks Its End

In his Physics (derived from phusis, the Greek for “nature”), Aristotle conceived of nature as a principle of change and rest. An individual thing is a compound of form and matter. Be it a rock, tree, fish, dog, or human, an individual thing – what Aristotle called a “this” or primary substance – come to be and persist through changes before ceasing to be. Coming to be and passing away involve substantial change. In other words, Aristotle accounts for the generation and destruction of an individual thing or substance, as when an acorn grows into an oak tree, and then that tree is felled to make a table. The tree persists through accidental changes, such as leaves and branches falling or breaking off. You are also a substance, enduring through various changes until death, but your pinkie finger, for example, is not. Like a leaf or a branch, the pinky is part of a substance. Think about it this way: Suppose your pinkie finger is disconnected from the rest of you. When detached from the body, it loses its defining function; it has no purpose independently of the body. Let’s look at the relation between substance and function a bit more closely.

|

|

A frog’s telos is in the tadpole. (Credits: HOS70, via Pixabay)

Central to Aristotle’s thinking about nature is that the principle of change and rest is not simply an external force pushing things around, as when a stick pushes a stone, but is internal to an individual thing – it’s what makes a rock stay on (or roll to) the ground, the kitten grows into a cat, and the sapling develops into a tree. Each thing has a core function, final purpose, goal, or telos.

Nature, according to Aristotle, is teleological. The telos of the acorn is an oak tree, and the telos of the kitten is a cat. Even inanimate things exist for the sake of some end, like the humble rock, which seeks, so to speak, the center of the Earth. For Aristotle, the human telos – or at least the ultimate purpose of a free adult male – is happiness, flourishing, or living well, which includes, crucially, virtues like courage and truthfulness.

We can see just from these examples that ancient thinkers conceived nature as governed by rules – or maybe that nature is itself a rule that directs the regular patterns of change. We can also see that thinking about nature as a complicated and dynamic system implicitly anticipates the dangers of meddling, as when humans began paving over wetlands or ignoring the consequences of pollution.

Nature is One Great Machine

Aristotle’s teleological view of nature held sway until thinkers in the 17th century inaugurated a mechanistic picture that has profoundly influenced the sciences as we know them today. Rather than thinking of nature as purposive, “natural philosophers” such as Sir Isaac Newton considered nature to be like a vast machine whose workings are determined by fixed and predictable antecedent conditions. Whether it’s how blood courses through veins, the planets move, or light travels, nature is a machine in motion – a machine whose workings are expressed mathematically.

The mechanistic view’s real origins date at least to the fifth century BCE. The Greek Atomists, Leucippus and Democritus, held that the universe consists of atoms (“uncuttables”) and the void. Everything is subject to the necessary laws of change – a picture closer to contemporary physicists’ thinking about change than to Aristotle’s.

So, is this what nature comes down to, substance in motion? It feels rather … sterile, doesn’t it? Think about it this way: If nature is one giant machine whose parts are fitted together by causal connections – from the stars down to a single-celled organism – then beliefs we have about things like God and free will are mere illusions.

(Credit: Alexas_Fotos, via Pixabay)

In Europe, a good number of thinkers were both enthralled and alarmed by this new worldview. Descartes, for example, worked hard to carve out a supernatural domain free from natural determinism. While our bodies, like any other material thing, are subject to the inexorable flow of causal forces, our minds – which include our will – are not. That’s because the mind is a different kind of substance from the body; it is an immaterial entity that, unlike extended material things, is not determined by things like force, velocity, or inertia.

Descartes’ dualism – the view that mind and body are two distinct kinds of substance – apparently solves one problem but creates another. If mind and body are two entirely different kinds of substance, how do they interact?

In the 1600s, Baruch Spinoza not only proposed a solution to the problem, but used a mathematical method to do so. There is one substance, Spinoza argued, which “we call God, or nature.” In other words, the universe (God or nature) is all there is. What follows necessarily from the nature of the universe, is an expression of that nature. So, you and I, stars and planets, trees and bears – we’re all modes of one substance, nature.

M51 is a spiral galaxy, about 30 million light years away, that is in the process of merging with a smaller galaxy seen to its upper left. (Credit: NASA.gov)

While Spinoza’s account is thoroughly deterministic, and while such a radical account of God flies in the face of the Jewish and Christian anthropomorphic views of the divine, it nevertheless provides a compelling way to think about what there is and how it got that way. Nature just is everything following its necessary course – Spinoza’s God is definitely not your Heavenly Father.

The Amsterdam Portuguese-Jewish congregation pronounced Spinoza in herem, a form of excommunication, when he was only 23, roughly two decades before he wrote Ethics. The herem remains in effect to this day.

Nature, According to Romanticism and Evolution

Thinking about what there is and how it works went through still more changes. The late 18th century saw the rise of both Romanticism and evolutionary theory – on the face of it, two very different views of nature that would seem to make strange bedfellows. They were, however, remarkably compatible. Romanticism, primarily an aesthetic movement in response to the sterile mechanical view of nature, emphasized dynamism, power, and vibrancy. For many, nature was equivalent to life and a source of moral instruction, artistic inspiration, and spiritual renewal.

(Credit: ROverhate, via Pixabay)

(Credit: ROverhate, via Pixabay)

By contrast, Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory, which accounts for changes in heritable characteristics over generations of living things, is deeply mechanistic – and arguably irrelevant to anything in the moral, artistic, or spiritual domains. Nevertheless, and even if nature’s end is simply itself – if nature’s goal is simply to persist – we might see an interesting connection.

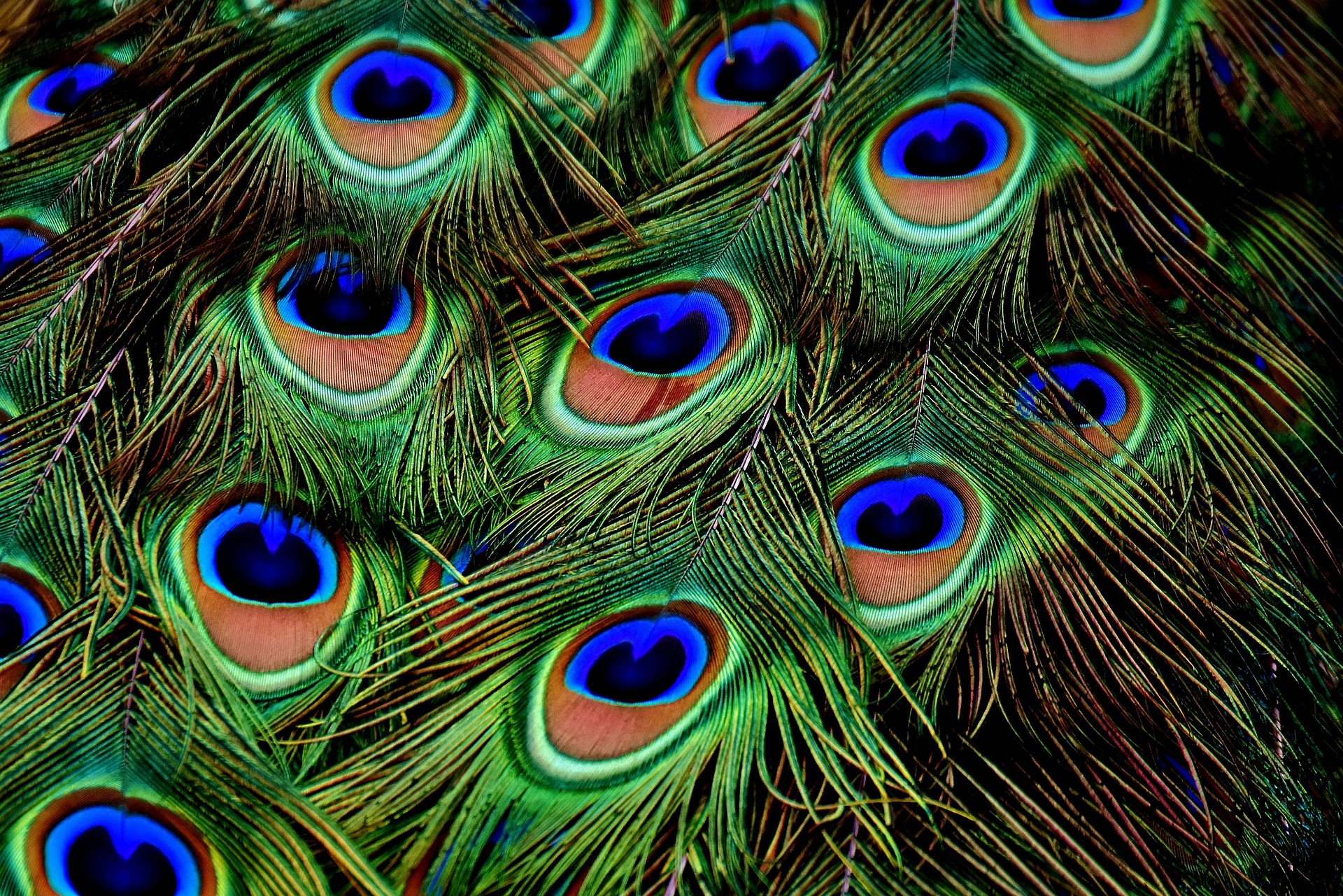

For the Romantics, nature is beautiful and creative, its impulse is to find ways to persist; Darwin might not have used such terms, but he was no less interested in explaining, for example, the exquisite delicacy of a butterfly’s wing. And though he did not see beauty as an element in the process of adaptation – he theorized that sexual selection accounted for nature’s beauty – he was not immune to its vibrancy and seeming exuberance.

Theorizing about nature, along with the development and progression of experimental methods and mathematics, eventually formalized into the various studies we today know as “science.” Today’s scientific thinkers work in narrow specializations ranging from anthropology and botany to zoology and physics to study nature.

So do philosophers. Subject areas like the philosophy of biology, philosophy of psychology, and the philosophy of physics, for example, focus attention on various aspects of what we think about when we think about nature. When the ancients looked up at the starry sky – the same one we see today – they were both awestruck and full of wonder. We know much more today about nature, but we are no less impressed by the fact that there is something rather than nothing.

Ω

Mia Wood is a philosophy professor at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California, and an adjunct instructor at the University of Rhode Island, Community College of Rhode Island, and Providence College. She is also a MagellanTV staff writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. She lives in Little Compton, Rhode Island.

Title image credit: Bessi, via Pixabay