Recent sailboat attacks by Atlantic killer whales recall 19th century Pacific Ocean encounters in which furious sperm whales rammed and sank two American whaling vessels. They were believed at the time to be acts of vengeance, the hunted becoming the hunter. This raises a question: In our closely studied natural world, can we still have sea monsters? Here we look at several candidates, some famous, others still mysterious, competing for the title.

◊

Lately I’ve noticed news reports of killer whales attacking recreational sailboats in unprovoked assaults on the high seas. What brought them to this is, like so much of the ocean, a mystery.

One explanation I like is that after a peaceful summer in which weekend sailors were quarantined on shore, the orcas were not at all happy with the revived activity and noise.

Another proposed reason is that the killer whales are fighting back following injury from commercial fishermen. Are these very large, fairly intelligent, sea-dwelling mammals growing more aware of the threat humans present to marine life?

Even as coral reefs are dying in warming seas, overfishing, plastic pollution, oil, fertilizer, and radioactive runoff are turning vast stretches of the ocean into dead zones. Though it’s wrong-headed to assign human motivation to any animal, it’s hard not to think that the bigger and smarter sea creatures, whose mammalian eyes, after all, resemble our own, are mad as hell and not going to take it any longer.

The killer whale assaults reminded me of earlier accounts from the 1850s, of sperm whales attacking whaling ships in the Pacific, sinking two of them with great loss of life.

Watch Moby Dick: Heart of a Whale now on MagellanTV

People naturally thought that these unexpected assaults by the enormous, enraged creatures were motivated by revenge. (That alpha-male sperm whales may have been aggravated by sounds coming from the ships was suggested by a naturalist decades later.) Inspired by the events, Herman Melville wrote Moby Dick, his sprawling masterpiece that combines natural history and a look at life on a whaling vessel into an operatic tale of insanity and vengeance.

Beware of Ketos: Poseidon’s Attack Animal

It is commonly observed that we know more about the surface of Mars than the bottom of the ocean. And it’s ironic that even as, starting in the 15th century, global navigation increased our knowledge of both the Earth and our Solar System, the seas remained a realm of mystery.

A 1603 star chart mapping the constellation Cetus (Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

For the ancient seafaring Greeks, the ocean was awash with gods and creatures who mainly did not mean well to mortals. The fiercest was Ketos (Cetus in Latin), an attack-monster Poseidon sent against humans unlucky enough to anger him. Ketos/Cetus mainly interfered with humans living, as most Greeks did, near the ocean. Early on it was portrayed as a great serpent; later depictions show it resembling a whale (with, however, the head of a dog).

Early astronomers made Cetus a constellation, with star guides placing it near the fishy constellation of Pisces. And its name was given to the study of whales, cetology.

Another summer news story, funnier than orcas attacking yachts, came from a small Massachusetts shore town. A big, blob-like creature with a tall dorsal fin, wallowing around its cove, concerned enough people to flood the local 911 emergency line.

Turns out, the beast was a sunfish, a stupendously ugly jellyfish feeder enjoying a maritime all-you-can-eat buffet. News reports added that the Massachusetts coast has seen an increase in great white shark activity as the offshore waters have warmed over the years. So, naturally, people were on edge.

Maybe we still don’t know what to make of the ocean deep. Maybe sea monsters are as much a part of the natural order of things as birds, lions, and turtles. But, even though many of the ocean’s stranger creatures have been retired – mermaids, sorry to say, are gone for good – we have no shortage of truly bizarre creatures, rarely-seen inhabitants of the ocean’s deepest zones that are still cause for wonder, and maybe some well-deserved fear.

A Best-in-Show Sea Monster?

Which got me wondering – in our well-studied, highly-catalogued natural world, can we have a modern sea monster? I’ll reluctantly concede that we’ll probably never see a furious dinosaur rise from the depths to flatten a city, like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms or Godzilla, but I submit that there are four solid standards to judge a modern sea monster, with several outstanding candidates for the title.

1. It Must Be A Menace to Humans

Right off the bat, a sea monster must threaten humans. It doesn’t matter if they’re familiar creatures. Just because orcas performed four shows daily at Sea World doesn’t mean you shouldn’t worry when a pod of them are after your boat. Likewise, the much-filmed great white shark qualifies as a figure of extreme dread.

Octopi and squid have legendarily dragged mariners to their doom, but those candidates for the prize must compete in the next category.

2. For Sea Monsters, Size Matters

To strike fear from the deep, it’s best to be big. Reaching 32 feet long and up to six tons, orcas certainly qualify. The somewhat smaller great white shark, topping out at 25 feet and 2.5 tons, in this instance punches above its weight in the sheer terror department.

_with_open_mouth_in_La_Paz,_Mexico.jpg)

A feeding Whale Shark (Image Credit: Matthew T. Rader/Wikimedia Commons)

The size champion, the largest fish on earth, at up to 62 feet, is the whale shark. It, however, is utterly docile and spends its days vacuuming up plankton, tiny shrimp, and fish eggs. Awesome, yes. Frightening? Not really.

The all-time sea monster size champion is the now-retired megalodon, which gave up the title for lack of prey 2.5 million years ago. It was a gigantic carnivore that probably resembled the great white, at twice the size. Some believe megalodons still stalk the ocean, but given their estimated need for warm, shallow water, a constant supply of enormous animals to devour, and with zero credible sightings, alive or dead, megalodons’ existence appears as unlikely as mermaids.

Before 20th century commercial and sport fishing over-stressed marine populations, it was not uncommon for individual fish and crustaceans to grow to sizes far larger than found today. The sudden appearance of enormous lobsters, manta rays, octopi, tuna, and sailfish could have easily frightened unwary mariners. But, alas, any freakishly big, though otherwise normal, candidates for the title of sea monster were hunted-out long ago.

Giant squid, measuring about 33 feet, and most of that in tentacles, tip the scale around a modest 400 pounds, which puts them them more in category

3. Is It Genuinely Frightening to Behold?

With a long, gelatinous body, eyes the size of dinner plates and a mass of constantly writhing, sucker-covered tentacles, the giant squid takes top prize in the nightmare competition.

Probably because of its otherworldly appearance, and rare sightings, the giant squid was model for the dreaded Kraken of Norse legend. It was able, according to myth, to wrap its tentacles around unlucky ships and pull them to the bottom of the sea. There may well be some really big Giant Squid lurking down there, but none have pulled mariners to their doom in a very, very long time.

.jpg)

1887 drawing of an anglerfish (Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Terror Honorable Mention must go to the deep-dwelling anglerfish. It’s enormous jaws are open constantly, showing rows of dagger-like teeth. A fleshy cord grows from its nose, with a tiny phosphorescent lantern at its tip to lure prey in its pitch-dark world. If pulled up in a net, it might give an unsuspecting fisherman a heart attack, but that’s about the extent of the danger it offers humans. Unfortunately (or maybe not), the largest variety of anglerfish maxes-out at three feet long. It also stays in its comfort zone, 4,000 to 5,000 feet deep.

Which brings us to the last, maybe hardest qualification for a modern sea monster,

4. It Must Be Shrouded in Mystery

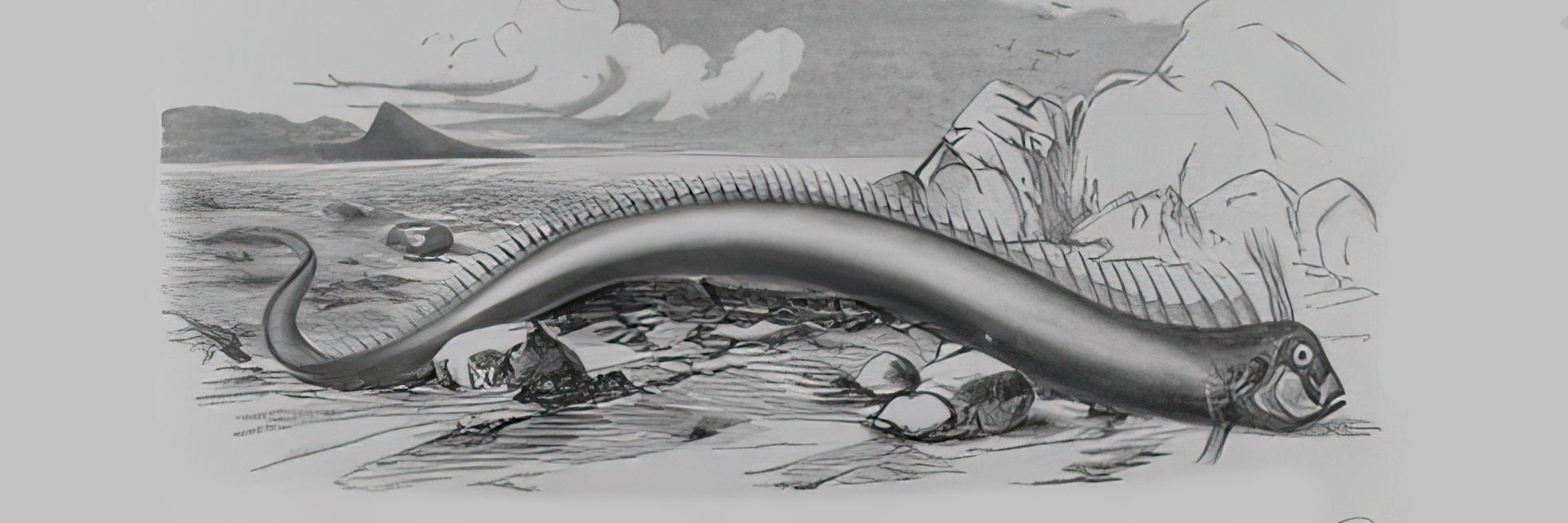

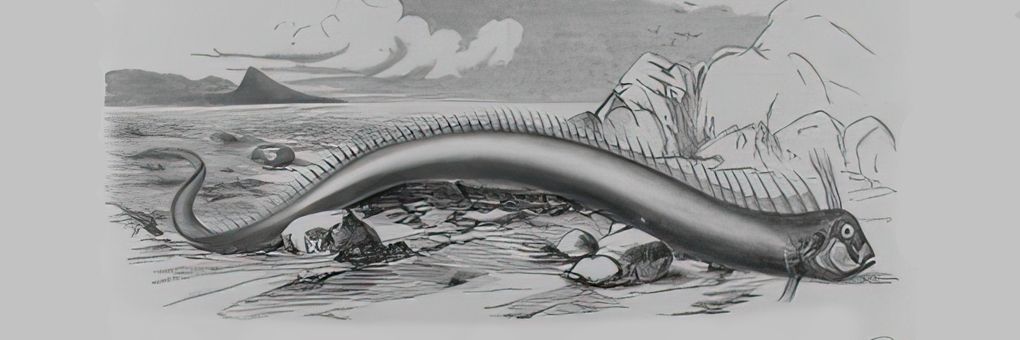

Top competitor here is the oarfish, an eel-like swimmer from 2,000 feet, with large eyes and nearly 400 spiky dorsal fins running the length of its body. The official longest measured specimen was 26 feet, though sightings report others at over 40. Live sightings are extremely rare, and oarfish studies are based on corpses washed to shore. (You’ll find a drawing of one, found on a beach in Bermuda in 1860, at the top of this article.) The oarfish certainly qualifies as, and probably was, the sea serpent of legend.

The equally elusive megamouth shark, a plankton feeder like the much larger whale shark, is both mysterious and pretty scary looking – as its name implies, its head is one big oral cavity. Discovered only in 1976, the megamouth is also tantalizing evidence that more large unknown sea creatures may still be down there.

Are There Sea Monsters Waiting to Be Discovered?

In 1998, the ecological mathematician, Charles Paxton, published a statistical study estimating the number of large (over two meters long) aquatic animals yet to be catalogued. A Cumulative Species Distribution Curve for Large Open Water Marine Animals graphed the number of sizable marine species discovered between the years 1758 and 1995. From that, Paxton’s statistical analysis predicts that as many as 47 large species remain uncatalogued, with an average discovery rate of one every 5.3 years. Paxton told The Economist magazine that he expects the yet-to-be-seen marine animals are mainly Cetaceans: whales, dolphins, and porpoises. But “a couple of new, totally weird sharks” are possible, too.

So, until a new contestant arrives, who takes the Best Modern Sea Monster Prize? As the only judge I hereby award it to the 32-foot long, 6-ton, angry, yacht-bashing orca. Even great whites don’t mess with killer whales. And now modern sailors have been put on notice that an old beast has some new rules for the briney deep. Still, it’s too bad that the orca isn’t more oarfish-like. A multi-ton, eel-fish, maybe 60 feet long, with a mouth full of razor-sharp teeth? With attitude? Now, that’s what I call a sea monster.

Ω