Our contemporary awareness of Ebola dates back only six or so years, to 2014, when one case in western Africa blossomed into a full-scale epidemic affecting not only that region but other parts of the world as well. However, decades prior to that outbreak – back in the 1970s – Ebola first started killing humans. Now, we can learn from the lessons that epidemic provided on how best to prepare for and treat a new viral outbreak. But have those lessons really been taken to heart?

◊

In December 2013, a young boy who lived in a remote village in Guinea, a country in western Africa, died of a mysterious cluster of symptoms. Within weeks, nearly everyone who came into close contact with the sick boy – or his corpse – had contracted the same symptoms and died as well.

At first, local and regional doctors who learned of these cases theorized that cholera was the cause of the fatal illnesses. However, not all the symptoms observed were germane to that preliminary diagnosis. So blood samples were sent to medical authorities in Guinea, who passed the samples to medical colleagues in Europe for further investigation.

It took some time – critical time lost in the case of a highly infectious pathogen – but soon the startling cause was revealed. A particularly virulent form of the Ebola virus, one formerly only seen in Zaire, had spontaneously arisen from this one case in Guinea and was now threatening to spread regionally, to neighboring countries Liberia and Sierra Leone, and potentially beyond.

Sister Marietta, a nurse, at the graves of ebola victims in Zaire, 1976 (Credit: Centers for Disease Control PHIL, via Wikimedia Commons)

A rapid response was more than needed; it was demanded. Doctors without Borders, known as Médecins sans Frontiéres in the primarily French-speaking country of Guinea, had been involved in the identification of this viral pathogen. They assembled a front-line team that was operating on the ground within a week. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S.’s Centers for Disease Control (CDC) also quickly deployed teams to examine patients and do contact tracing for the infected, hoping to get the upper hand on this rapidly spreading infection.

This marked the beginning of the largest outbreak of Ebola known to date. With a coordinated response delayed precious weeks due to the late diagnosis, the epidemic, which extended into 2016, eventually spread across continents, affected American citizens, and caused more than 11,000 deaths. The mortality rate for the widespread epidemic ranged from 25 to 90 percent, affecting areas within Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone differently.

Where – and How – Did Ebola Originate?

The 2013–2016 outbreak by no means marked the start of Ebola infecting humans. Recorded cases of the virus date back to 1972, when a Western doctor working in Zaire, now called the Democratic Republic of Congo, contracted a nonlethal case while performing an autopsy on an African student who had died mysteriously of a hemorrhagic fever.

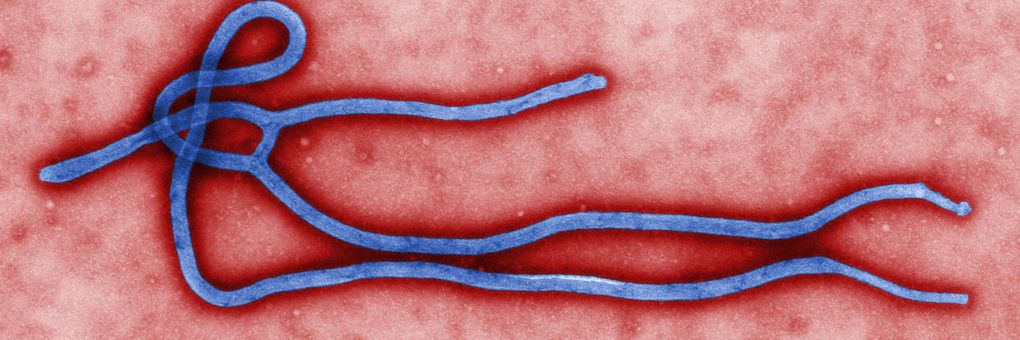

It was five years later when – after the virus was identified in 1977 – this doctor’s blood was retroactively tested and found to possess antibodies to Ebola. The year 1977 marked the end of the first significant outbreak of what was then a novel virus, which started in a small town in Zaire called Yambuku and caused 280 deaths. The Ebola virus is classified as a filovirus, referring to its filament-like shape and relating it to a cousin in the virus world called Marburg (named for the location of the lab in Germany where it was first identified in 1967).

Ebola is named for the location of its first discovery in Zaire, though its discoverers chose not to call it Yambuku, fearing that the small town would face fear and shaming as a result. Instead, the discoverers chose a nearby river as the virus’s namesake: the Ebola, whose name is the French corruption of its indigenous name Legbala.

The Ebola virus exists in bats, particularly fruit bats, who are immune to its ill effects; humans (and, we have learned, other primates) have no natural immunity. And that is merely the first of many reasons the virus is so deadly.

Why Was the 2014 Ebola Outbreak So Lethal?

Without immunity, we have no means to mitigate the severity of symptoms caused by an Ebola infection. And the symptoms, caused by the destructive path the virus takes through the body, can be very deadly in themselves. The primary route of transmission is from bats to humans, or from bats to animals that are encountered by humans, including chimpanzees and gorillas. (In parts of Africa, fruit bats are eaten, as is meat from other wild animals, collectively called “bush meat.”)

Bats are not affected by the virus they carry, but the effect on humans is quite different. And proximity to an infected bat means proximity to the virus, since the bats shed virus particles that can stay infectious even on the ground. Remember the infected Guinean toddler, now known as “child zero”? The path his disease took began with him playing around a tree in his village where fruit bats were known to nest. It’s presumed that he was infected by closeness to the bats rather than direct contact; he most likely inhaled dust from the earth around the tree that contained viral particles.

A villager in Bakonga, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2018 (Credit: Lianne Gutcher/World Health Organization)

Once the Ebola virus enters the human body, it starts creating havoc. It penetrates blood cells, including those in the respiratory tract, eyes, and more, then quickly starts replicating exponentially. Though symptoms may not be evident for several days or even weeks, once they appear the situation gets rough very quickly.

Like the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (which causes the COVID-19 disease), early signs of infection with Ebola include flu-like symptoms. From there, however, symptoms vary widely, though either disease can result in mortality for the infected person.

Early symptoms of Ebola include fever, muscle pain and weakness, and sore throat. Soon following these, as the virus infects more and more cells, come much more serious, and life-threatening, symptoms, including internal and external bleeding. The infected human body – alive or dead – is also highly contagious, making contact extraordinarily risky.

How Did the World React to the 2014–2016 Epidemic?

Fortunately, rural West Africa is not a center of multinational trade and travel. If it were, we may have had an epidemic of much larger regional and international reach. Instead, the virus’s growth rate – even given its high infectiousness – was nothing like the “novel coronavirus” that spread from the highly populous, and well-traveled, province of Wuhan, China, beginning in 2019.

Rather, the Ebola virus was diagnosed, with intervention following from Médecins sans Frontiéres, WHO, the CDC, and other international agencies on the ground in various western Africa locations. Of course, that did not stop the spread into the towns and cities of Guinea, and then into regional neighbors Liberia and Sierra Leone. What did stop this highly infectious virus before it became a pandemic was coordinated international action.

Unfortunately, viral outbreaks don’t only carry disease with them. As Professor Guido van der Groen, co-discoverer of the Ebola virus, explains in the engrossing MagellanTV documentary Ebola Exposed, “The spread of Ebola is not only the spread of the virus, it is also the spread of fear.” And fear can lead to some desperate, even deadly, outcomes. The key to addressing the fear of infection is not malicious targeting of at-risk groups; rather it is communication, delivered effectively, truthfully, and without delay.

Colorized scanning electron microscope image of the ebola virus (Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases)

This is what WHO did by quickly disseminating information in the affected regions of western Africa, and around the world. By declaring this an international health emergency, WHO could work in concert with other organizations, especially the CDC, in arresting the spread of Ebola.

The U.S. president at the time of the 2014 start of the Ebola epidemic, Barack Obama, named an “Ebola czar,” Ron Klain, to coordinate the government’s response to the crisis. His performance was praised for providing leadership “from the system for evacuating infected Americans from West Africa to the disposal of Ebola-related hospital waste.”

Assessing the Response to the Epidemic: What Went Well

In summer 2016, in a special supplement to its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the CDC published an exhaustive review of the actions it undertook to address and, finally, halt the rising infection rate of the Ebola virus. Among the many findings is a list of key actions instrumental in eventually containing the outbreak.

In brief, these encompass:

- Rapid deployment of on-the-ground support where the virus was spreading.

- Case detection and contact tracing.

- Encouraging cultural changes to prevent transmission.

- Working to develop a vaccine.

- Establishing risk assessment procedures for persons traveling from West Africa to the U.S. and other parts of the world.

- Training American hospitals to prepare properly for the arrival of infected persons.

- Quickly developing and distributing screening tests.

In the end, all these tactics worked to lower the incidence of Ebola outside western Africa. Only 11 people in the U.S. were diagnosed with the virus, a large portion being health workers, and two of this small population died.

Critiquing the Response to the Epidemic: Too Late, Too Slow

Despite the best efforts to provide care and support in an integrated way, however, there were complications. Many of these factors encountered by the CDC, WHO, and other international aid groups were enumerated in various critiques made of the response efforts by, among other organizations, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the CDC itself.

The CDC’s self-assessment included many factors that worked against an early and more rapid and effective response:

- Wide geographic spread of the infections.

- Population mixing and mobility.

- Disease transmission in dense urban areas.

- Early unfamiliarity with the disease.

- Lack of effective public health infrastructure.

- General distrust of government and of health care and aid workers.

- Delayed start and slow rollout for coordinated international response.

A report printed in the British Lancet medical journal mentioned these factors as well, and added others: Early response was hampered by the lack of infrastructure in Guinea and the other affected nations that would have allowed for rapid, early detection, reporting, and response to the outbreak. The report also highlighted the assessment that the international response was slow, poorly coordinated, inflexible and inadequate.

The NIH, in addition to agreeing with many of the issues above, also noted that investment in prevention and preparation should be made in advance of – rather than parallel with – another outbreak.

One main question remains, however: Have we really learned these lessons so that we don’t repeat them? I believe the answer to this, sadly, is no.

What Have We Learned?

It is hard to comprehend how the coordinated, ultimately successful fight against Ebola did not translate into an effective rapid response to the novel coronavirus just six years later. The difference between the 2014 response to the Ebola outbreak and the current struggle against COVID-19 is astonishing and distressing.

Early communication, which would have helped prepare at-risk persons for the potential of infection, was limited, incomplete, and understated. Both in China and the U.S., there was a lack of transparency that hindered preparedness. And now, with the establishment of the U.S. as a major center of the coronavirus pandemic, we have severe shortages of testing kits, protective equipment, and medical devices such as ventilators to help treat patients.

What we do not have a lack of is fear. And that is tragic. We could benefit from the lessons learned from our experience with Ebola and other infectious disease epidemics – if only we would.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title image: Ebola virus virion by Cynthia Goldsmith, CDC via Wikimedia Commons.