During the Cold War, there were more nuclear accidents and other shocking incidents involving nuclear weapons than many know. Amazingly, none of these events ended with the detonation of these terrifying weapons, perhaps leading to a sense of complacency among people around the world. How close have we come to nuclear war? How was the world spared, and who saved us? Our occasionally fearless commentator is on the story.

◊

While shaving the other day, my thoughts drifted to the Cold War and nuclear weapons. Such ruminations are sort of a hobby of mine, and they’re usually harmless. But that morning I might have taken it a tad too far when I had a eureka! moment and scrawled a simple formula on the bathroom mirror with my Gillette Foamy: CW + NW = NA (+M3), which translates to “Cold War + Nuclear Weapons = Nuclear Accidents (+ Miscommunication, Miscalculation, Mischief).”

This Grumplesteinian Epiphany (if I may be so bold as to coin a term) was prompted by watching a two-part documentary called Broken Arrows: The Lost Bombs of the Cold War, which concerns several accidents during the 1950s and ’60s in which U.S. Air Force bombers crashed and lost control of their nuclear weapons. Pretty hair-raising stuff when you consider what would have happened had any of the bombs’ nuclear cores detonated. Bye-bye, Goldsboro, North Carolina. Hasta la vista, Palomares, Spain.

The good news is that for various reasons (different in each of the incidents) the nuclear bombs didn’t go off, hundreds of thousands of people weren’t vaporized or worse, and we were free to whistle in the wind and watch all 249 episodes of The Andy Griffith Show without worrying too much about Aunt Bee and the other fine people of Mayberry meeting an atomic demise.

The bad news is that the Grumplesteinian Epiphany™ still applies, even after the Cold War supposedly ended. Humans being humans, our mistakes are as inevitable as pratfalls in slapstick comedy. But nuclear accidents and the three M’s have rather greater consequences than, say, a Chevy Chase sketch in an old episode of Saturday Night Live.

A Hair’s Breadth: Cold War Capers and Nuclear Accidents

Broken Arrow incidents were more common during the Cold War than you might think, but they comprise only one type of nuclear accident that has scared the bejeezus out of people since the first atomic bomb was exploded in Alamogordo, New Mexico, in 1945. For example, we all watched with horror reports of the shocking disasters at Chernobyl, Ukraine and Fukushima, Japan in which nuclear reactors melted down, massive amounts of radiation were released, lives were lost, and hundreds of thousands of residents were displaced.

“Broken Arrow” is the U.S. military term for an incident involving nuclear weapons that doesn’t involve the likelihood of nuclear war. Examples would include nuclear weapons or components that are lost, misplaced, or accidentally exploded. Oddly, in Native American culture the broken arrow is a symbol of peace.

Other types of nuclear scares – both during and after the Cold War – come under “Miscalculation, Miscommunication, Mischief” in my semi-brilliant equation. The danger of miscalculation was evident in the Cuban Missile Crisis and lurks wherever nuclear-armed adversaries stare each other down, from the western border of Russia, to the Middle East and South Asia, to the Korean Peninsula. Miscommunication has been a worry since the U.S. and the Soviet came within a donkey hair’s breadth of igniting a nuclear Armageddon during the Missile Crisis.

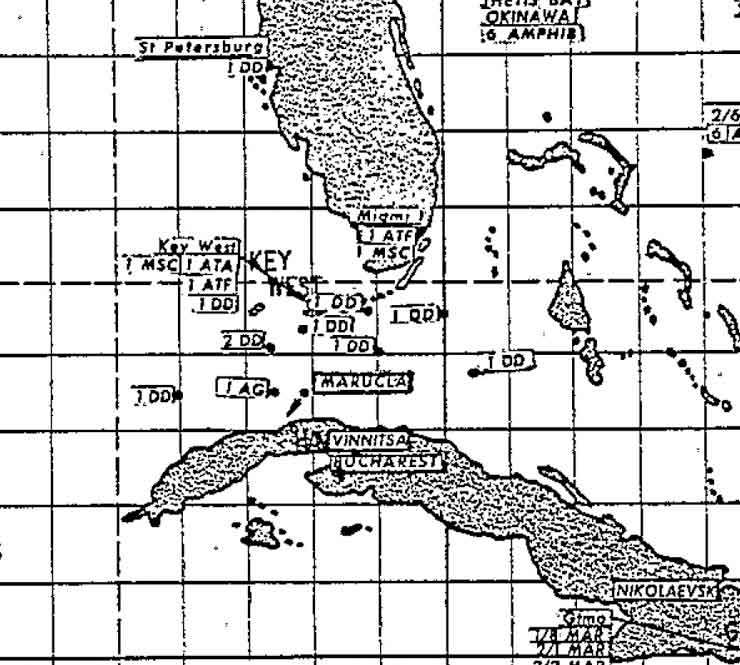

Declassified 1962 map used by the U.S. Atlantic Fleet showing the position of American and Soviet ships at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis (Source: United States Navy, via Wikimedia Commons)

And mischief? That’s one that doesn’t get talked about enough in public, but I’ll bet it keeps nuclear security experts up at night. Consider the implications of the growing cyber warfare capabilities of any number of nations (and even non-state actors) and the possibility of some brilliant idiot gaining access to command-and-control systems of a nuclear power. Let those scary thoughts sink in, and then call your doctor for a sleeping pill prescription.

Let’s face it: There are more routes leading to a potential nuclear catastrophe than there are freeways in Los Angeles. To most of us, though, the one we’re most familiar with from the Cold War era is the Cuban Missile Crisis. So, allow me to share a personal perspective.

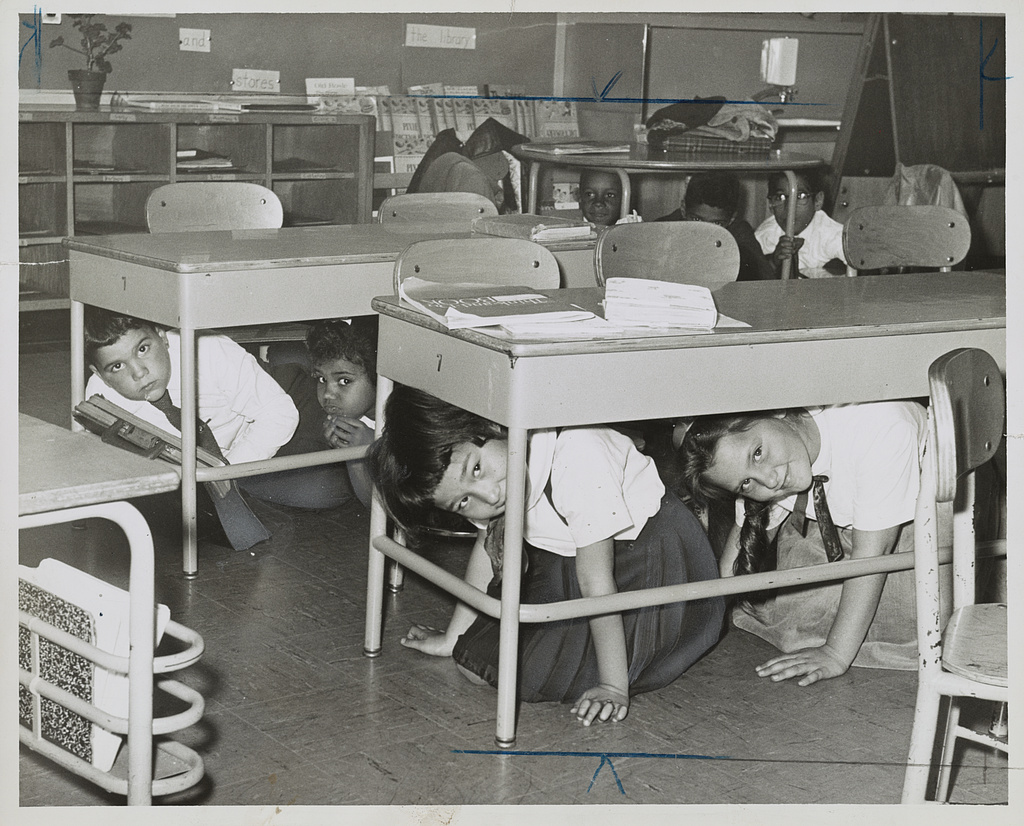

“Duck and Cover”: How to Survive a Nuclear Attack

When I was a lad growing up in the 1950s and ’60s, I was trained to “duck and cover.” That’s probably a meaningless phrase to millions of schoolkids today, so here’s a rough translation for those of you from a younger generation less conditioned to fear a nuclear holocaust: When the air raid siren sounded, we were told to drop to our knees and cover our heads, preferably under a desk or some other piece of sturdy furniture. If we did this – and if our prayers were well-received by the Almighty who was naturally assumed to love America and its NATO allies more than the godless commies – we might have lived a little longer, assuming The Bomb didn’t detonate too nearby.

"Take cover" drill practice, 1962 (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

As for our mums and dads, and our big brothers outside at football practice, well, their chances wouldn’t have been so good. But not to worry, there would be some grownups left to help us along. Just like the grownups who let the whole thing get out of hand in the first place. Just like the grownups who managed the bloody Cold War!

Yes, we might have survived but, to paraphrase military planner Herman Kahn, would the living have envied the dead?

Nukes in Cuba, America at Defcon 2

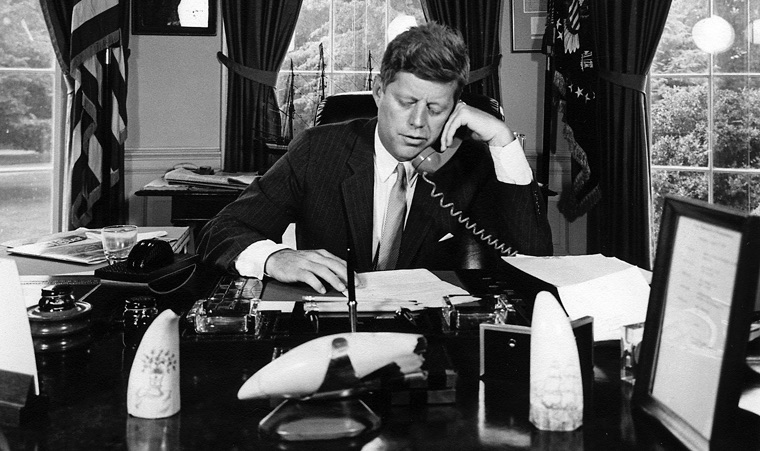

I almost got to put the “duck and cover” routine into practice during the Cuban Missile Crisis (CMC). In the fall of 1962, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and his Kremlin Kronies (which was not a Russian rock and roll band) decided it would be a right-fine idea to station a bunch of nuclear-tipped missiles in Cuba. U.S. President John F. Kennedy, whom Khrushchev misjudged as a callow, skirt-chasing bon vivant, wouldn’t tolerate the blatant violation of the Monroe Doctrine or the commercial sanctity of Florida’s upcoming tourist season.

Never mind that the U.S. had backed the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba by hapless anti-Castro counterrevolutionaries only a year-and-a-half earlier, or that the U.S. had deployed nuclear-armed Jupiter medium-range ballistic missiles in Turkey and Italy. Let’s just say that Kennedy and his advisors didn’t think that installing such missiles in Cuba, only 90 miles or so from Key West, was one of the more brilliant plans that the Russkies ever launched (so to speak). Pretty soon, the Strategic Air Command was at Defcon 2, the second-highest level of alert for nuclear war.

President John F. Kennedy in Oval Office, White House, 1962 (detail) (Source: Abbie Rowe, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston, via Wikimedia Commons)

The U.S. uses the Defense Readiness Condition (Defcon) scale for the status of military forces. The levels are:

Defcon 1: “Cocked Pistol” - Nuclear war is imminent

Defcon 2: “Fast Pace” - One step from nuclear war

Defcon 3: “Round House” - Force readiness higher than normal

Defcon 4: “Double Take” - Increase in intelligence and security measures

Defcon 5: “Fade Out” - Routine state of readiness

So, for 13 tension-filled days that fall, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. teetered on the brink of a nuclear World War III. It would probably have started with a salvo of missiles fired from Cuba to the Southeast U.S., and as far north as Washington, D.C. At the time, my family lived in the Danger Zone.

I remember distinctly my dear departed parents watching President Kennedy’s televised speech to the nation on October 22. My dad Abe turned to my mum Rose (yes, she was Abie’s Irish Rose) and said, “This could be it.” As a precocious nine-year-old with the language skills of Oscar Wilde, I didn’t mince words and asked, “Say what?”

Nuclear Torpedoes in the Caribbean

If you’re one of those smarty-pants contrarians who don’t believe we really came all that close to nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis, then an incident that occurred at the height of the crisis on October 27 (known by CMC historians as “Black Saturday”) should feel like a bucket of ice water poured on your head.

President Kennedy, wisely rebuffing the reckless recommendations of his military advisors, had ordered a blockade of Cuba rather than a full-scale military attack on the island. That fateful Saturday, as part of the blockade mission, a group of U.S. Navy destroyers were harassing a submerged Soviet Foxtrot-class submarine, the B-59, like hounds at a hunt. The American ships were dropping “signaling” depth charges, which are used to force a submerged vessel to come to the surface.

Soviet submarine B-59, forced to the surface by U.S. Naval forces in the Caribbean near Cuba, October 1962. (Source: U.S. Navy photographer, in the collection of George Washington University National Security Archive, via Wikimedia Commons)

Unbeknownst to the Navy commanders prosecuting the chase, the B-59 had an ace up its sleeve: a nuclear torpedo outfitted with a 10-kiloton warhead.

Vasili Arkhipov Saves the World

Who would be crazy enough to use such a weapon? Well, Valentin Grigorievich Savitzky, the beleaguered sub’s captain, that’s who. He was prepared to fire that torpedo to destroy as many of his pursuers as possible (even though he knew it would be a suicidal gambit). And the B-59’s political officer, an ideological fanatic (a job requirement for political officers embedded in military units) named Ivan Semonovich Maslennikov, agreed.

Ivan Semonovich Maslennikov in 1945 (Source: Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, via Wikimedia Creative Commons)

To be fair, the B-59 was deep underwater, and Savitzky and Maslennikov were unable to communicate with their Soviet superiors. For all they knew, World War III might already have begun. Under those conditions, Soviet Navy protocol permitted the sub’s captain and political officer to make the decision about use of a nuclear weapon. But in this case the command situation was a bit more complicated.

Also aboard the B-59 was Captain Vasili Arkhipov, who was serving as Captain Savitzky’s second-in-command – but was simultaneously commander of the entire flotilla of Soviet submarines operating in the area. This blessedly peculiar arrangement meant that the decision to fire the nuclear torpedo required the agreement of all three officers. And Arkhipov put the kibosh on his comrades’ impulse.

Vasili Arkhipov posthumously received the inaugural Future of Life Award, in 2017. Accepting the award on her father’s behalf, his daughter Elena said, “He did his part for the future so that everyone can live on our planet.”

Had the B-59 fired the torpedo, the pressure on Kennedy to respond in kind would have been irresistible, and the tit-for-tat escalation would have been nearly impossible to stop. Nuclear war between the United States and the U.S.S.R. would have been all but certain. Farewell, New York. Da svidaniya, Moscow.

And here’s the kicker: The fact that the B-59 had been armed with nuclear weapons was not revealed by Russia until 2002. So, if you stopped reading about the Missile Crisis in, say, 1999, you missed the news.

Spasiba, Captain Arkhipov.

Another Russian Saves the World

With all the sturm und drang these days about Russia’s attempts to disrupt Western democracies, it is good to keep in mind the heroic example of Vasily Arkhipov. And, amazingly enough, he’s not the only Russian whose steadiness in the face of potential nuclear catastrophe has allowed us to continue down the primrose path of civilizing the world to death.

Howzabout a round of applause for Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov who, in September 1983, was on duty keeping track of potential missile threats on the Soviet early warning system. Imagine the chill that must have gone down his spine when the system indicated several American missiles were on their way to targets in the Soviet homeland. Yikes!

,_in_1973.jpg)

Radar screen (Source: U.S. Navy, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Petrov, to his lasting credit, sensed there was something wrong with the picture he was seeing. He decided not to report the warning immediately for fear that his superiors would overreact and launch a full-scale nuclear counterstrike. In the end, the supposed U.S. “attack” turned out to be harmless sunlight reflecting off completely unthreatening clouds.

Once again, spasiba, Lieutenant Colonel Petrov.

OMG! Another Russian Saves the World!

Let’s share an Occupy Wall Street–style group fingersnap for noted dipsomaniac Boris Yeltsin, who was President of Russia in January 1995 when an anonymous military officer handed him the briefcase containing the country’s nuclear launch codes and said something to the effect of “It’s go-time, Comrade President!”

It seems that a team of Russian radar technicians had been watching their glowing screens and, to their horror, saw the unmistakable signature of a missile launch from a not-so-distant spot in the Arctic Circle. They dutifully reported the sighting to their superiors, who then dutifully passed the dreaded news up the chain of command. The speed with which this passing of the buck was accomplished is truly breathtaking, for the dutiful officers had only minutes to get the alarming news to the Russian leader.

Yeltsin, who had been planning an evening at the Bolshoi Ballet, was pissed (in two senses of the word). His immediate response has been lost to history, as none present could quite make out the words that came slurring from his lips. However, it might simply be that he said something like, “Why in the name of Ivan the Terrible would the Americans launch a single missile as a first strike? Get me that bumpkin peasant Bill Clinton on the red phone!”

It was later learned that American and Norwegian researchers had launched a rocket from an island in the Arctic Circle to study the aurora borealis. They had routinely forewarned Russia and all other potentially concerned countries of their plans, but apparently the message didn’t get to the poor Russian radar jockeys who nearly lost it when the harmless missile’s blip appeared on their screens. Miscommunication can be a bitch.

And a big spasiba to you, President Yeltsin. Have a vodka on me in the afterlife.

Could a New Cold War Lead to a Nuclear Winter?

Remember those halcyon days after the Berlin Wall fell, the Soviet Union fell to pieces, and nuclear weapons were being sacrificed like pawns in a game of chess? Those were the days, my friends, long summer days of contentment and security in the Land of Hopes and Dreams. The Cold War was over. We won, they lost.

But was it really that simple? Is anything? I’m guessing Mr. Putin in Moscow doesn’t take that view. And probably not Mr. Xi in Beijing, either. In fact, according to what I read in the press that the U.S. Intelligence Community has concluded that Russia and China have been coordinating efforts more than at any time since the 1950s in the midst of . . . the Cold War. And I’ll bet you every greenback in my wallet that it’s not “fake news.”

.jpg)

Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, July 26, 2018 (Source: President of the Russian Federation, www.kremlin.ru, via Wikimedia Creative Commons)

I also read the other day that the U.S. and Russia have nixed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which banned the development and deployment of a whole class of nuclear-armed missiles. The Russians have allegedly been violating the treaty for years, and war hasn’t broken out. So what’s the big deal?

Now listen to me carefully: One of the critical purposes of the INF Treaty was to eliminate weapons that shaved precious minutes off the decision-making time a leader would have before ordering a retaliatory attack. Think about it: The next time some sleepy Russian technician mistakes sunlight reflecting off clouds for an incoming nuclear missile attack and passes the alert up the chain of command, the Boss might not have time to think it through and choose to save the world. Is that a big enough deal? Remember the Grumplesteinian Epiphany™: CW + NW = NA (+M3).

I don’t know about you, fellow citizens of the world, but I feel a chill in the air. It seems like there’s a cold wind blowing against the empires – and winter is coming. Let’s just hope it’s not a nuclear winter.

Ω

Title image: Aftermath of a nuclear test carried out in Licorne, French Polynesia, 1971. (Source: Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization [CTBTO], via United Nations)