Pandemics have plagued human societies since the dawn of history. Let’s explore four notorious pandemics of the past that changed the course of history.

◊

Diseases have been a part of everyday life from the beginning of time and, as we are learning from hard experience, that’s not going to change any time soon. While we have both written accounts and physical evidence of their dire effects on human societies, the causes of some illnesses remain a mystery to this day. For example, in the year 250 C.E. the Plague of Cyprian killed an estimated 5,000 people per day in Rome alone. The cause? Unknown. Fortunately, though, not every case is a mystery, and the pandemics of the past can teach us a lot about the diseases of the future. Let’s take a look at four of them.

1. The Plague of Athens (435-430 B.C.E.)

During the Peloponnesian War, an infectious disease of uncertain origin reached Athens, then spread across parts of Greece and the eastern Mediterranean. The Plague of Athens, which is actually believed to have begun in sub-Saharan Africa, killed nearly 100,000 people – approximately one-third of the city-state’s population at time – and was likely the most lethal epidemic in the history of Classical Greece.

The Greek historian Thucydides wrote, “people in good health were all of a sudden attacked by violent heats in the head, and redness and inflammation in the eyes, the inward parts, such as the throat or tongue, becoming bloody and emitting an unnatural and fetid breath.” Fortunately, Thucydides recorded the outbreak in his History of the Peloponnesian War, and meticulously identified the symptoms and experiences of those afflicted (including himself).

.jpg)

Plague in an Ancient City by Michiel Sweerts, c. 1650 (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

While the disease that caused the plague is still unknown, contextual clues like the ones Thucydides passed down to us suggest that this epidemic may have been caused by typhoid fever or an Ebola-like disease. What isn’t disputed, though, is the extent to which it shaped history. During the outbreak, the Athenian general and statesman, Pericles, was killed by the disease, and with him, the Athenian democracy. The weakness the plague created led to the eventual defeat of Athens, affecting both the war and life in ancient Greece and, in turn, altering world history.

2. Yersinia Pestis – “The Plague”

Chances are, we’ve all heard of this dread disease, or at least have heard the satirical “Bring out your dead” chant from the 1975 cult classic, Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Think of any medieval scene, and you’ll probably picture “the Plague”: that pesky disease carried by rats and fleas caused by the Yersinia pestis bacteria. But the aptly-named pandemic didn’t just strike once, and may have existed in more forms than you may have thought.

There are three types of plague: bubonic, septicemic, and pneumonic. Both the bubonic and septicemic forms result from contact with infected fleas or animals. The deadliest of the three, the pneumonic strain, is the only form that can be spread among people directly.

The first known appearance of plague occurred from 541 to 542 C.E., when the Plague of Justinian left an estimated 30–50 million people dead. So devastating was the pandemic that scholars believe it contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire. It began in the ancient Egyptian city of Pelusium, and flea-infested rats carried the disease across the Mediterranean Sea on boats sailing to Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire and seat of Emperor Justinian. From there it spread across Europe, Asia, Arabia, and North Africa, killing what may well have been half the world’s population of the time.

Hundreds of years later, the Yersinia pestis bacteria resurfaced to cause the Black Death, or Bubonic Plague, in the years 1347 to 1351. Estimates vary, but this outbreak of the plague wiped out 30–50 percent of Europe’s population. The pandemic was so devastating that it took more than 200 years for the population to return to its previous level.

Victims of the Black Death (Design by Edward Corbould, lithograph by F. Howard, c. mid-1800s)

You see, the plague had never truly disappeared after the Plague of Justinian, and it didn’t disappear after this wave either. The plague-causing bacteria persisted, and a series of “Great Plagues” cycled through Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, leaving over four million people dead. Included in these outbreaks were the Great Plague of London, the last major appearance of the Black Death, which was brought under control by new isolation laws and social distancing.

Luckily, “the Plague” isn’t something we’ve had to deal with in the everyday life of the modern world. But don’t let your guard down – it still exists.The CDC still receives a report of the one to 17 cases of the plague per year. It even resurfaced in the news after a child in Idaho contracted the disease a few years ago.

3. The Smallpox Pandemic and Other American Plagues of the 16th Century

During the age of Age of Exploration, lands were discovered, wonders were compared, and diseases spread like wildfire.

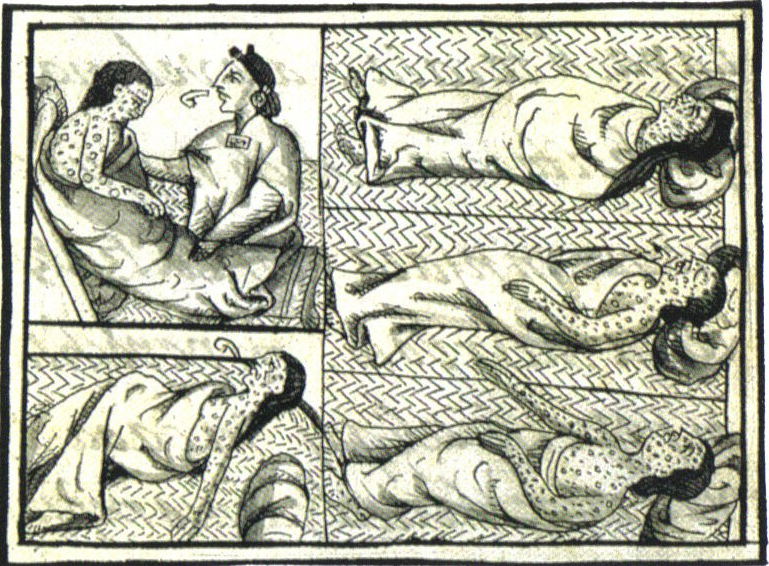

The conquest of the Americas remains a source of historical controversy, but one fact is indisputable: The ships that brought European explorers to the Americas also brought something else. Unbeknownst to the passengers, silent killers lurked beneath the ships’ decks, ready to debark at the docks. The stowaways? A handful of infectious diseases that would flare into pandemics. Deadly gifts to the people of the New World.

Smallpox and a cluster of Eurasian diseases brought to the Americas by European explorers wreaked havoc on the newly discovered Americas. The Smallpox Pandemic of 1520 alone killed an estimated 95% of Native Americans, and is said to have decreased Mexico’s population from 11 million to one million, and is considered the second deadliest pandemic to date.

Smallpox victims (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Smallpox was a feared disease long before – and after – it came to the Americas. The disease fluctuated between endemic and epidemic after its origin, but no one knows for sure where it started. Caused by the Variola major virus, it is believed to have first appeared during the early days of animal domestication, and evidence of it has been found in ancient Egyptian mummies. It remained endemic to Europe, Asia, and Arabia for centuries before arriving in the New World, bringing devastating consequences to a population of defenseless humans who had no prior contact with the disease.

Although the disease had grave effects – it killed an estimated 400,000 people in Europe, per year, during the 1800s – those who survived the disease obtained permanent immunity. But those weren’t the only ones to gain immunity; the first ever vaccine was created to ward off smallpox by Edward Jenner in 1796. With thanks to the vaccine, the World Health Organization declared smallpox to be eradicated in 1980.

Smallpox wasn’t the only disease that the unsuspecting North and South American natives were exposed to. Named using the Aztec word for “pest,” the Cocoliztli Epidemic (1545–1548) was believed to have killed as many as 15 million people in Mexico and Central America.

4. The H1N1 Virus and the “Spanish Flu”

The H1N1 virus was similar to the Plague in that it has gone by many names and surfaced many times, causing various degrees of sickness and even global pandemics. The so-called Spanish Flu (1918–1919) was probably the most infamous of its appearances in history.

We’ve all been hearing about this one lately, what with comparisons being drawn between it and the current COVID-19 pandemic. Like the crisis we're currently going through, the Spanish Flu was a global phenomenon, but it was far more catastrophic than COVID-19 has been in 2020. It infected an estimated 500 million people (about one-third of the world’s population at the time) and left as many as 50 million dead.

Another similarity between the H1N1 and SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) is that both are zoonotic, as both crossed to humans from other species – H1N1 from pigs, and SARS-CoV-2 from bats (possibly through another species).

And, like COVID-19, the Spanish Flu struck a human population that had little or no defense against its ravages. Worse, it showed up in the last year of World War I, and it spread like wildfire among troops on both sides of the conflict who just happened to be in the age range most susceptible to it – 20 to 40 years old. It’s probably fair to say that influenza was as crucial to the final outcome of the war as were machine guns, for the disease killed soldiers almost as effectively as the guns.

"Spanish Flu" victims in hospital ward (Credit: National Museum of Health and Medicine, Washington, DC)

The H1N1 virus was incorrectly believed to have originated in Spain. Why? Because the virus spread during World War I, and Spain, being a neutral nation, was allowed to publish freely early accounts of the illness. But just because they were the first to report it, doesn’t mean they were the first to get it. You can understand why some Spaniards are a little prickly about calling it the “Spanish” flu.

While the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 was the deadliest of the 20th century, it wasn’t the only time the H1N1 virus spread globally. In 2009, the H1N1 virus stuck again, claiming an estimated 200,000 lives – this time under the moniker “Swine Flu.” The outbreak was caused by a new strain of H1N1 that originated in Mexico and primarily affected children and young adults – 80 percent of the deaths were of people younger than 65.

It may seem like a crazy notion, but pandemics are something that we will likely be battling through the end of time. Yes, modern medicine and superior living standards leave us more protected than we were in ancient times, but if the recent outbreak of COVID-19 has taught us anything, it is that alone is not enough. History repeats itself – as do outbreaks. And there’s no denying that the pandemics of the past can teach us a thing or two about the one of our present day – and those of the future.

Ω

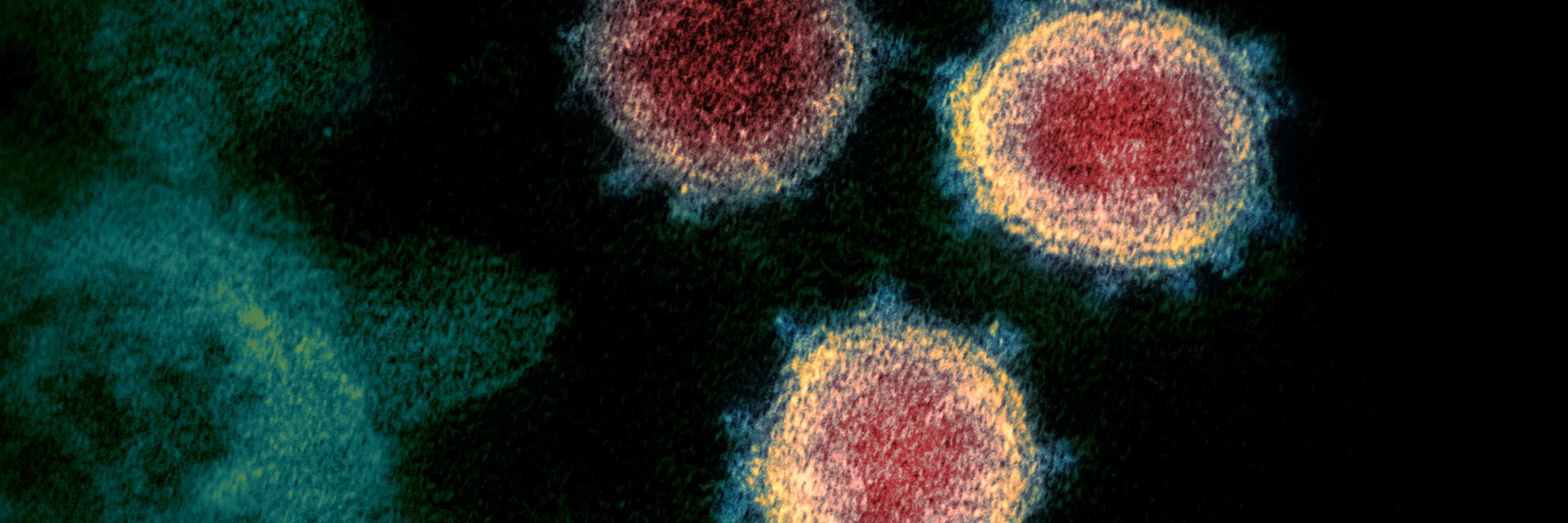

Title image: SARS-CoV-2 by NIAID-RML via Wikimedia Commons.