Many people around the world are concerned about the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, which causes the disease named COVID-19. This is neither the first appearance of a coronavirus affecting humans, nor the most lethal. Coronaviruses in humans run the gamut from the annoying (the common cold) to the deadly (SARS and MERS, among others). The most dangerous of these coronaviruses are those that have spread – like SARS-CoV-2 – from animals to humans; this type of transmission is called zoonotic.

◊

The appearance of a previously unknown coronavirus in Wuhan, the capital of China’s Hubei province, in late 2019, has been an ongoing source of concern since the first infected people started exhibiting symptoms. The coronavirus, called SARS-CoV-2 for its genetic similarity to SARS, has proven to be very contagious. It has spread from central China throughout that vast country and across borders to at least two dozen other nations. Crowded cities and convenient air travel have contributed significantly to its rapid transmission. The disease caused by this new coronavirus is called COVID-19.

Although its specific biological origin is not currently known with certainty, it has been determined to be a “zoonotic” pathogen, meaning that it originated in at least one species of animal, passing to humans either directly from that animal, or through a so-called “vector” (or host), usually an insect or other airborne pest that carries the virus without suffering any symptoms.

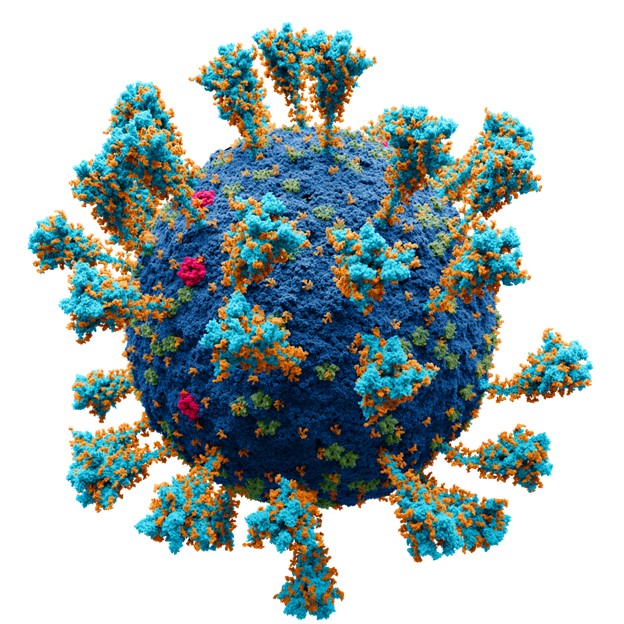

SARS-CoV-2 virus repesentation (Credit: Alexey Solodovnikov/Valeria Arkhipova, via Wikimedia Commons)

But it’s not the first coronavirus to affect humans. It’s not even the first coronavirus to be spread zoonotically. That distinction goes to SARS, or “severe acute respiratory syndrome,” which originated (also in China) in 2002, and ran its course over the next two years. There are many lessons that we have learned from the SARS epidemic around the world that will help in addressing the fear, even panic, that many people have experienced.

SARS: Our First Experience with a Zoonotic Coronavirus

In early 2003, a medical professional working in China with persons experiencing flu-like symptoms traveled to Hong Kong to attend a relative’s wedding. Though he didn’t know it at the time, he was infected with a previously unknown illness that he helped spread throughout the world.

As recounted in the MagellanTV documentary The Virus Empire (available for U.S. viewers), the doctor began exhibiting symptoms that he spread to multiple people through close contact – in hallways, elevators, and other public areas. He then infected members of his extended family also attending the wedding.

This locus of contagion originating in Hong Kong to points from western Europe to Southeast Asia was the first sign of the ailment that became known as SARS. This highly contagious viral infection spread through casual, even glancing, contact, making it a silent and surreptitious agent. The method of contagion is called “droplet transmission” because, simply, the virus is spread via airborne droplets of fluid produced by infected individuals through coughing, sneezing, and the like.

Spread Aided by Official Silence in China

Although officials in China knew of the existence of the troubling new respiratory disease, this was not shared within the country – and especially not internationally. Instead, the Chinese government clamped down on information gleaned from early cases and hampered reporting of the news. This information gap allowed the infection to spread from rural China into Beijing, its largest mainland city, and grow to epidemic proportions within the country.

Viruses are the most abundant and diverse pathogens known. They are classified based on their appearance and physical traits. For example, coronaviruses are generally spherical. The prefix corona specifically refers to the crown-like appearance of the protuberances that spike out from the roundish surface of the virus.

Even then, the Chinese sought to minimize the growth of information about the disease, underplaying its severity by calling it “atypical pneumonia” and, later, by underreporting its spread into Beijing by a factor of seven. This delay in sharing vital data on the infectiousness of the virus enhanced the severity of the outbreaks both within and outside China, and certainly contributed to the number of deaths worldwide attributed to SARS.

Subway riders wearing masks during COVID pandemic (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The mortality rate over the course of the SARS epidemic, which lasted from 2002 to 2004, was 9.6 percent. That correlates to a worldwide infection number of approximately 8,100 cases and 774 deaths. While the number of infections from SARS-CoV-2 is higher than SARS, the recovery rate from COVID-19 is also higher. And though the mortality rate is, to date, about 3 percent, the high recovery rate means that, for many, the effect on those infected is no worse than a severe cold or the flu.

It is sobering to realize that, even after the lessons learned from the course of SARS, the Chinese government would still be suppressing information about infections. But that appears to be exactly what has happened. Disturbing reports came to light in early 2020 when it was learned that the first doctor to report on the new coronavirus had been silenced by Chinese authorities when he attempted to spread warnings about the virus. Sadly, that doctor himself ended up a fatality of the crisis after he was infected by patients he was treating.

During the early spread of the SARS virus, the Chinese were less than fully cooperative with the World Health Organization (WHO). At that time, representatives from WHO were not allowed to investigate diseases in a country without a specific invitation from the host country to do so. In the absence of this invitation, WHO medical researchers and pathologists could not publish any information on the origin or behavior of SARS – so, no public mention was allowed until the Chinese relented. (Later, the rules under which WHO operates were changed for the public’s benefit, though specific countries can still restrict access to medical information within their borders.)

How Did SARS Appear? Lessons to Learn

Before SARS, the existence of coronaviruses was well-known. Some, like the type associated with about 20% of common colds, are well-established in humans and are the cause of much seasonal suffering, but are rarely fatal – except in very young or old patients, or those with compromised immune systems.

However, SARS presented something new when it was first reported and studied. It was found to have jumped from an animal species to humans, which had not been seen before among coronaviruses. Eventually the culprit species was identified to be the civet cat, a forest-dwelling wild animal that had become a culinary delicacy among certain regional populations of southern China.

Civet cat in Kape Melo Farms, Philippines (Credit: Rbalmonia, via Wikimedia Commons)

Since the outbreak of SARS and its link to civets, the Chinese government has cracked down on the hunting, raising, slaughtering, and eating of the cats. While it can’t be ascertained for certain how the SARS coronavirus migrated from that wild species to its human hosts, any exposure to civet meat has been determined to present risk.

The animal origin of the new coronavirus is currently under investigation. A mutated variant of SARS, the precise transmission route to humans is not yet known with certainty. The origin is potentially in a wild or domesticated animal, and one current suspect is the pangolin, a long-snouted, ant-eating mammal whose scales are often used in traditional Chinese medicine.

Trade in pangolins and their parts is illegal in China, though a strong black market exists for these undomesticated mammals. The hidden nature of this illegal trade makes it all the more difficult for researchers to track down reliable information on human-pangolin contact.

The World Health Organization estimates that 61 percent of all human diseases are zoonotic, in that they originated among animals and jumped over to humans. Moreover, 75 percent of new diseases discovered over the past decade are zoonotic as well.

MERS, a Coronavirus Associated with Camels (and Bats)

A separate coronavirus that slipped from animal to human and caused illness and fatality is MERS, or “Middle East respiratory syndrome.” All instances of infection with this pathogen have been tied to the Arabian Peninsula, with the country of Jordan being the epicenter of infection. MERS became an epidemic around 2012, and, while it’s not known why the outbreak began then, new cases have declined dramatically. Its cause has been attributed to close physical contact with camels.

Recent research into the ultimate source of this coronavirus indicates that camels serve as a “reservoir” of the virus, but that it most likely originated in bats and was transmitted through bites to camels. Bats are vectors of the virus in that they are able to transmit it without suffering from symptoms of illness. The specific means of transmission to humans are not clear, but eating camel meat does not seem to be a cause. Rather, it’s possible that the virus may have been inhaled environmentally, with camel droppings and other secretions being likely avenues of infection.

Camels serve as a "reservoir" of the MERS virus (Credit: Salehdk999, via Wikimedia Commons)

Nearly 2,500 cases of MERS have been reported overall, and it is very contagious. Perhaps most alarmingly, its mortality rate is approximately 35 percent. There is no MERS vaccine available to prevent the disease in humans, and post-exposure treatment is focused on symptom relief as well as treatment to support organ function. Although the most recent outbreak outside Arabian nations was reported in South Korea, in 2015, that infection was associated with an individual who had recently visited the Middle East.

The Search for Effective Treatment

When an endemic infection like SARS or MERS comes to light, speed and size of response are key to getting the infection under control and attenuating the risks to humans. An organization like WHO or the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) will conduct a multipronged attack to search and test for both the origins and causative factors in transmission. As quickly as possible, other research commences: animal study, the search for effective treatment, and the quest for a vaccine are all equally important, and research into all three areas is concurrent, as much as possible.

Viruses, including the coronaviruses discussed here, can’t be treated by antibiotics. Antiviral therapy can be effective, when that treatment is available, but the best resource for public health is the identification of a vaccine and its wide deployment, which can take time. A SARS vaccine was developed but never used since the disease came under control before the vaccine was ready.

Among the factors that promote interspecies viral transmission are, as noted above, crowding and overcrowding in public spaces in developing areas, including such environments as markets and public transportation. In addition, the rapid rise of international air travel from formerly isolated regions to other population centers also tends to cause the spread of pathogens.

The Role of Rapid Urbanization and Climate Change

It’s necessary to add several other conditions of our current age to the list of factors that contribute to the spread of disease. Global travel, tourism, and trade play large roles in connecting formerly separated populations. Spreading urbanization of former undeveloped areas – such as clearing forests for agriculture – also causes upheavals and an increase of contact between wild animals and human populations. Newly established homesteads in former wilderness areas often result in urban centers without proper waste management, which boosts health risks.

And global warming is an undeniable factor as well. Climate change:

- Makes transmission seasons (i.e., warm weather) longer and more intense;

- Spreads the geographic locations of outbreaks; and

- Affects agricultural practices due to shifts in average temperature or rainfall.

Habitat destruction, such as is happening in the Amazon and in Africa, is a particular threat. It eliminates the native home grounds for countless species, especially rodents, which carry hantavirus and can easily infect humans in the newly populated areas where these animals live. In fact, ongoing changes across the planet are exposing humans to an onslaught of new viruses and infections, more than we ever encountered in the past. And we’re hardly acclimated to our new threats.

Must We Panic? A Measured Response Can Save Lives

Based on the information presented here, it may seem like panic is an understandable reaction to the threat of virulent infections such as SARS and MERS. But getting swept into a panic over the threat of infection is never warranted.

There are universal and widely accepted means of avoiding infection. And they’re easy to implement. If you’re concerned that you may come into contact with a source of infection, consider taking as many of these 10 preventive actions as you can:

- Keep your hands clean, and wash them with soap for a minimum of 20 seconds after every potential exposure.

- Cover your mouth when you sneeze or cough, preferably into the crook of your arm, and never reuse a tissue.

- Keep dirty hands (yours, or other’s) away from your eyes, nose, mouth, and other mucous membranes.

- Keep doorknobs and other frequently touched surfaces clean and disinfected.

- Avoid or limit your exposure to people exhibiting symptoms of illness.

- Stay safe around pets and other domesticated animals, especially reptiles (turtles), amphibians (frogs), and livestock (e.g., live chickens).

- Prevent mosquito, tick, and flea bites with repellant and nets, if necessary.

- Handle raw food safely.

- Research local diseases prior to traveling, and protect yourself as appropriate when in new environments.

- Avoid petting zoos and open-air livestock markets where freshly-butchered meat is sold.

Viruses and other pathogens have been with us from the earliest days of human beings’ existence on Earth, and we’ve been infected with and by them ever since. In our extraordinarily fast-moving world, our exposure to them will only continue to increase. The best we can do is to be vigilant and use counter-measures to limit their spread. Any rational response is better than panic.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image credit: U.S. Centers for Disease Conrol and Prevention, via KUAR/NPR/Public Radio from UA Little Rock)