This year has seemed like a never-ending procession of 50th anniversaries, and we still have months to go. What was so special about 1969, and what were some of the low and high points of that incredible year? We asked our intrepid – but often incorrigible – staff writer, Padraic Grumplestein, to give us his take on the Manson murders, the infamous Altamont Music Festival, and the Moon landing. We should have known we’d get more than we bargained for!

◊

I’ve always had a thing for pop culture anniversaries, and 1969 provided enough of them to keep wordsmiths pecking at their keyboards all through this long, blood pressure–raising year.

The same was true of 1968, of course, and I did pitch the idea for an article about that year’s crop of 50th anniversaries to my editor last summer. At the time, he stopped toking on his vape pen, blew out a cloud of scented mist, and said “Grumplestein, if you make a joke about the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy or Dr. King, you’re dead to me – and to every decent editor in the English-speaking world!”

I thought, who did he think I was, Tucker Carlson? I had no intention of dissing Kennedy or King, both of whom were revered by my family. But, not wanting to be declared dead to my editor (or any that I might need in the future), I put the idea on a shelf. And eventually, like an Anthony Bourdain dining misadventure, it came back on me.

So, I warily visited my editor and pitched a similar article about anniversaries from 1969. To my surprise, he said, “What the hell? What’s the worst thing you could write about Altamont – or Charles Manson?”

Charlie Manson’s Celebrity – and Other Long-Lasting Curios of 1969

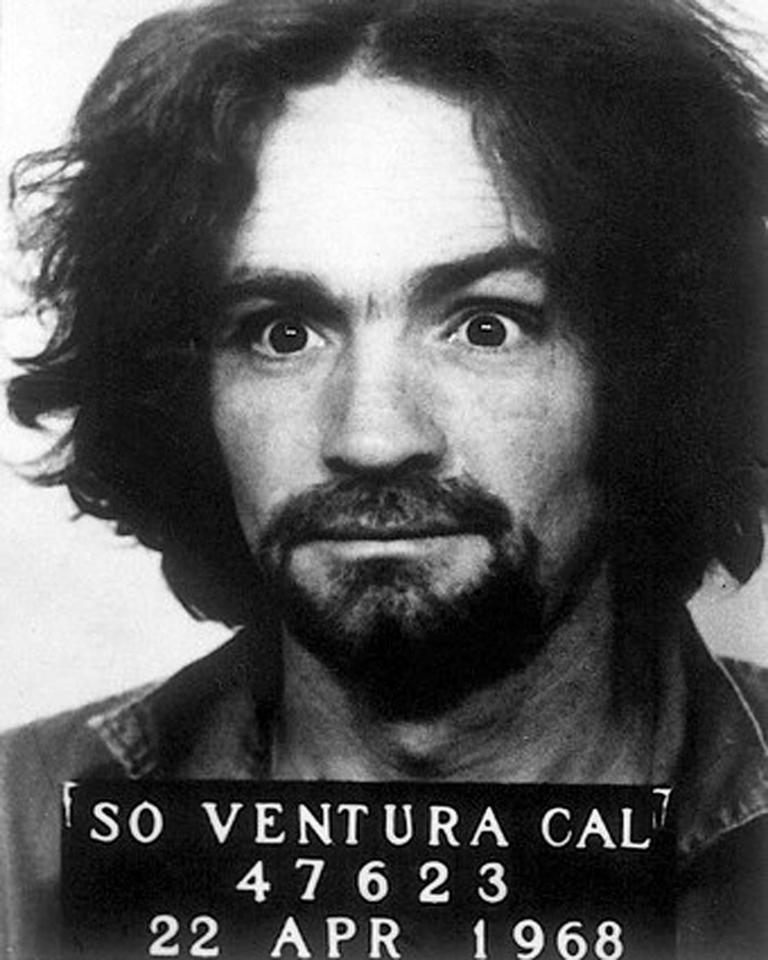

Speaking of Manson: Fifty years ago this summer, the demonic little wannabe rock star declared helter skelter on Los Angeles with murder and mayhem in the Hollywood Hills. What a schmuck! He died in 2017 in prison, and you’d think that we’d have buried his memory along with his scrawny tattooed body . . . but, no, guys like Charlie never seem to die for good. They’re like celebrity zombies forever wandering our cultural landscape.

Charles Manson mugshot, 1968 (Source: California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

Why is this? Why is it so easy to remember Manson’s cursed name and so hard to remember the names of his victims (except for actress Sharon Tate, of course)? Well, look no further than America’s twisted celebrity culture. Charlie has been on the celebrity pop chart for half a century, longer than Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. He and his meretricious minions have had enough books written about them to warrant a special shelf at Barnes and Noble. They’ve been featured in TV mini-series and movies (most recently Quentin Tarantino’s Hollywood-centric opus, set in 1969) and been the subject of documentaries up the wazoo. (Even my benevolent employer, MagellanTV, has a doc or two available).

You see, dear readers, it doesn’t matter how you get there, but once you’re on the Hit Parade of Fame, people’s fascination with everything you do is locked in – sometimes for generations. Political careers get built on such flimsy scaffolding. I’ll bet if Charlie Manson had run for president in 2016, he would have gotten more votes than Putin’s footsie-partner and Green Party candidate Jill Stein and not-ready-for-prime-time Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson combined.

Look, I’m all for compassionate treatment of prison inmates with mental health issues – and Manson was obviously as bonkers as Rasputin. Whether he was a sociopath, a psychopath, or the spawn of Satan, I don’t know. But I’m pretty sure of this: Charles Manson was, like his fellow serial killers, the personification of evil in the real world, and no dose of psychotropic medication is powerful enough to cure evil. As my sainted Irish mum would say, Go mbrise an diabhal do chnámha (That the Devil will break your bones).

‘Men of Wealth and Taste’ - The Rolling Stones Go to Altamont

Now that I’ve introduced the Devil into the story, may I inquire whether you have any sympathy for him? Mum didn’t, but my dad sure did. Abe Grumplestein was part of a small but fervent group of middle-aged Rolling Stones fans back in the 1960s. While his business partners were convinced Muzak was the zenith of American musical culture, Dad was enjoying an early mid-life crisis that manifested itself when a slew of blues-influenced bands from Britain invaded American radio airwaves – and the Stones were, for him, the apotheosis of that music. When my high school friends came by to hang out, he’d crank up Beggar’s Banquet and Let It Bleed to full volume on the old cabinet-style hi-fi in our living room. Frankly, having a “cool dad” can be kind of embarrassing.

Dad’s reverence for the Rolling Stones nearly went off the rails, in December 1969, when Mick Jagger and his mates played the infamous Altamont Speedway Free Festival in California. If the Woodstock mega-festival a few months earlier was the Eden of ‘60s hippie culture, Altamont was its descent into Hell.

“I’ve never taken the concept of black masses seriously. . . . But if there is such a thing as a black mass, Altamont would be my reference point.” —Joel Selvin

Other than the financial bath that the Woodstock promoters took when the festival was declared free of charge, the only things that went wrong were the rain and the “brown acid” that assembled masses were advised not to ingest. At Altamont, though, the counterculture lost its innocence. Or, as Dad said, “A band called the Grateful Dead recommends a vicious biker gang called the Hell’s Angels to perform stage security – what could possibly go wrong?”

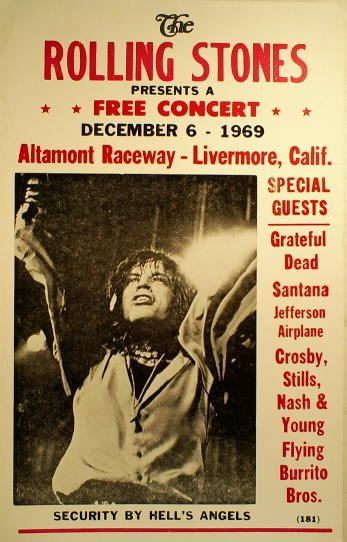

In fact, as Rolling Stone, the magazine, reported, “everything went perfectly wrong.” An all-star lineup of rock bands had been cobbled together for the event, but the venue was repeatedly changed before the promoters, in desperation, accepted an invitation to stage the concert at the auto racing speedway called Altamont. By that time, they had all of two days to get their act together, and they never quite did.

Altamont free concert poster, 1969 (Source: Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

The result of the poor planning was even worse execution. The stage was too low, and the crowd was too close. Amenities, such as portable toilets, were in short supply. Cars were stolen. The vibe was surly and unsettling, and fights erupted. The Grateful Dead, those fabled friends of the Devil, refused to take the stage on account of the unruly crowd and the violence all around them. As the Rolling Stones performed their anthemic “Sympathy for the Devil,” a scuffle broke out in front of the stage between white Hells Angels “security” and a black concert-goer named Meredith Hunter who, apparently in terror, pulled a gun. Hunter was stabbed and stomped to death.

In fact, when the so-called “festival” came to its bitter end, four people were dead: Hunter, two people hit by a car, and some poor guy who dropped some bad acid (probably stored without refrigeration since Woodstock). Maybe the Stones, who seemed to have so much fun cultivating their satanic image, learned that the Devil doesn’t make such a splendid playmate. Or, as my disheartened father said, cribbing another Rolling Stones album title, “The children of the counterculture have become December’s Children.”

Rocket Man Neil Armstrong Says His Peace . . . on the Moon

My exasperated editor has been monitoring the progress of this article on Google Docs, and now he’s heading over to my desk like an irritated Ed Asner on the Mary Tyler Moore show. “Grumplestein!” he roars, “What’s all this gloom and doom stuff? Manson? Altamont? Didn’t anything good happen in 1969?”

“Well, sir, James Taylor made his first appearance at the Newport Folk Festival. He sang ‘Fire and Rain’ – there wasn’t a dry eye in the audience.”

“Grumplestein!”

As I am writing, what I know – but my editor doesn’t, just yet – is that Taylor sang his soon-to-be beloved tune in Newport, Rhode Island, on the historic date of June 20, 1969. And right after he finished performing it, the concert organizers halted the show to share the broadcast of the Apollo 11 Moon landing with the folkie audience. Now that, patient readers, was a moment when world history slammed into popular culture to fuse into an unforgettable alloy of time and place. Where were you? Everybody knows.

Astronaut Neil Armstrong, photo taken by Buzz Aldrin during Apollo 11 flight, 1969 (Source: NASA / Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

Everyone then also knew it could have been “flying machines in pieces on the ground,” but Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong had been rehearsing some different words for the singular occasion: “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind” – maybe not as eloquent and touching as Taylor’s song, but etched into humanity’s collective consciousness like few other words in all of history.

That night, my parents, my little sister Siobhan, and I were gathered around our almost-new Admiral color television. But don’t expect me to recall every detail. (If you’re looking for a play-by-play account of that night, watch a good documentary.) What I remember comes in flashes: the radio traffic between Mission Control and the astronauts, the lunar landscape getting sharper as the “Eagle” lander descended toward the surface, the grainy black-and-white visual of Armstrong stepping so carefully down the ladder to leave the first footprint on the Moon – and to utter his slightly garbled, immortal words. (Believe me, if Stanley Kubrick had shot the scene on a Hollywood soundstage, the video and audio quality would have been a whole lot better.)

I’d like to wax on about how we joined a half billion TV viewers around the world in awe of the moment, how it made us want to buy the world a Coke and sing in perfect harmony, and how our family embraced in a long group hug. But that’s not how the Grumplestein family rolled. In fact, there had been a simmering dispute between Mum and Dad all day that had percolated to near-boiling – something about whether Mick Jagger’s vocals could properly be considered “singing” – and the whole thing blew up when electric power to the house went out. So much for perfect harmony.

The ‘60s End with a Bang (Not a Whimper)

Milestone anniversaries burrow into our consciousness like musical “earworms.” Sometimes pleasant, sometimes not so much – but always hard to quiet once they settle in.

Every time I hear the Beatles’ “Helter Skelter” (or U2’s later cover of it), the horror Charlie Manson unleashed hovers in my mind. When I hear Merry Clayton’s soaring voice singing “Rape! Murder! It’s just a shot away,” in the chilling crescendo of the Stones’ “Gimme Shelter,” the debacle of a December day at Altamont weighs heavy. And when I think of the Moon landing, it’s hard not to hear Richard Strauss’s tone poem “Also sprach Zarathustra,” which was brought into pop culture by Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

My father loved ‘60s music – and he loved taking me to movies. Easy Rider, a classic of American New Wave cinema, combined the two. Having missed it when the film was released in the summer of 1969, we had to wait until it came around for its second run. (Remember, there were no VCRs, DVDs, DVRs, or streaming video back then.)

Our chance to see the movie came in December at the local drive-in, which was unusual for being open year-round. So Dad and I bundled up, hopped into the old Chevy Impala, and headed for the show. The film was only half-finished when snow began to fall, but my father refused ever to leave a movie until the credits had finished rolling.

Through lightly falling snow and intermittently sweeping windshield wipers, we watched Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper motoring down a two-lane, rural Louisiana road to their fate at the hands of a redneck truck driver with a shotgun. And so it was that we saw the restless idealism and free spirit of the ‘60s meet its end.

It might have been the most memorable couple of hours I ever spent with my dad.

Ω

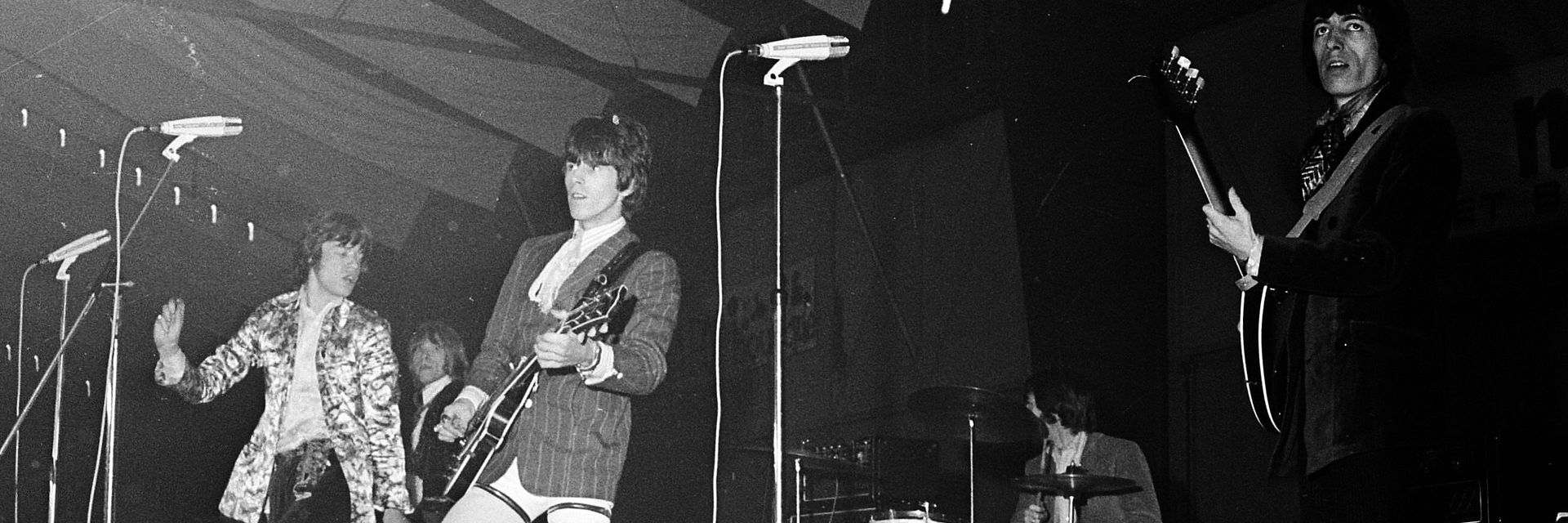

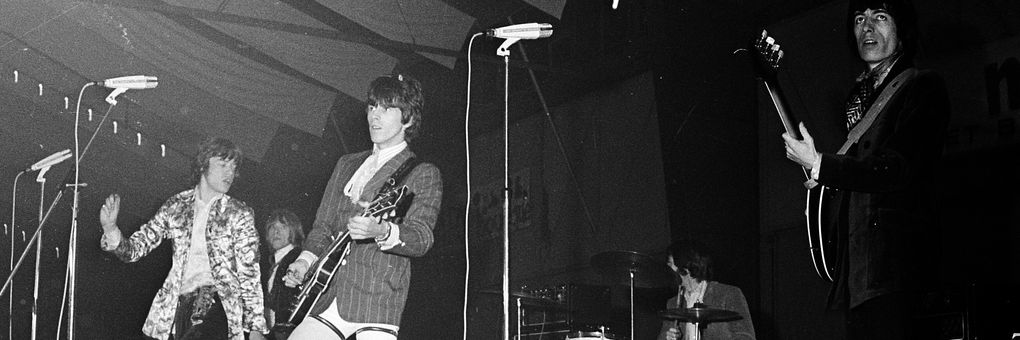

Title image: Rolling Stones in concert, Houtrusthallen The Hague (NL), April 15, 1967 by Ben Merk (ANEFO) via Wikimedia Commons.