Though migration is incredibly dangerous and energetically costly, birds still make these voyages each year. Why, then, do birds continue their annual migrations?

◊

Imagine that you are forced out of your home twice a year, when the weather changes. You have no choice but to leave; there aren’t enough resources for you anymore. As you make your way toward a place that is more hospitable, you encounter myriad threats and challenges. Predators, fatigue, and even physical obstacles stand between you and survival. Despite all this, you continue on your journey until you reach your destination, however far away it may be. And when the weather changes once again, you turn around and do it all over.

It’s called migration, and it’s a reality that many bird species face twice each year. Though it may seem absurd that any animal would subject itself to this kind of hardship, it’s a necessary journey that some creatures must take.

For more on avian migration, check out the MagellanTV documentary “Secret Routes For Migratory Birds.”

Why Do Birds Migrate?

In North America, many of us are familiar with the quintessential honking, chittering, and squawking of migrating birds once the autumn leaves begin their descent to the ground. It can be sad to watch our winged friends leave us, but their departure is necessary for their survival. In fact, their migration is largely triggered by diminishing food availability when fall arrives and common sources of nourishment such as insects, seeds, and fruit become less abundant.

To adapt to this shortage, birds migrate to regions where food is more available. They fly south to their winter homes and take advantage of accessible food. Then, when temperatures begin to rise once again, migrating birds instinctively head back to their summer territories to increase their chances of securing a good spot for nesting in the spring, in addition to taking advantage of replenished food sources. This is the annual cycle of a migratory bird.

Canada geese in flight (Credit: Jeffrey Hamilton, via Unsplash)

Different Types of Migration

The migration patterns of birds are incredibly varied in terms of direction, distance traveled, and even altitude. For instance, most migrating birds in North America fly south for the winter and back north for the summer. However, the usual migratory direction for Southern Hemisphere birds is reversed, with a bird like the orange-bellied parrot flying north from its summer home in Tasmania to its winter grounds in northern Australia.

Or take the amazing migration of the bar-tailed godwit. These birds migrate all the way from Alaska to New Zealand each year, a staggering 8,000 miles one way, often without stopping. Compare this to the mere 300-meter migration of a blue grouse, and it’s easy to see the variability among different species.

This variety can also be found in the direction of migration. While we often think of migration as latitudinal, or from north to south, birds also migrate longitudinally, or from east to west. The California gull provides a great example of this. These birds inhabit the western half of the United States, migrating further west to the coast for the winter.

Another common migration pattern is altitudinal, at which the violet sabrewing, a hummingbird species native to Mexico and South America, is a master. These birds can be found at elevations from about 2,000 feet all the way up to 8,000 feet! However, once the breeding season has concluded, they fly back down to about 1,500 feet.

To learn more about hummingbirds, check out the MagellanTV documentary Hummingbirds, narrated by David Attenborough.

You might ask, what about birds that don’t migrate? Good question. In fact, over half of all bird species don’t migrate at all. The main reason is that those species have access to sufficient food all year round. When colder temperatures reduce resources such as insects and fruit, birds that rely on them are forced to relocate to areas where they are readily available.

However, birds that eat seeds and other foods that are plentiful year-round usually do not relocate, even if staying put means they have to brave bitter temperatures. The tufted titmouse is a great example of a non-migratory species. These small but mighty birds live throughout the eastern United States, withstanding harsh winters by caching seeds to eat during the colder months.

Osprey hovering in search of prey (Credit: David Clode, via Unsplash)

How Do Birds Know When and Where to Migrate?

For many of us, the start of the fall is broadcast most clearly by honking gaggles of geese, their iconic V-shaped flights dominating the cool evenings. To know the right time to begin their great migrations, birds pay attention to the length of days. When they notice the sunsets are earlier and the temperature is falling, an instinctive alarm goes off – it’s time to get moving someplace warmer!

Most birds actually prefer to migrate during the nighttime. A major reason for this is that the air is cooler after the Sun dips below the horizon, making it easier for the birds to embark on long flights with less threat of overheating. Other reasons include that the cooler night sky makes for less turbulence, and fewer predators makes for a safer journey.

But how do birds know exactly where to go? Amazingly, both nighttime and daytime migrators take their cues from the heavens. Night-fliers use the Moon and stars to navigate, and those that fly by day get their navigational fix from the Sun’s position in the sky and Earth’s magnetic fields!

Gull soaring above the sea (Credit: Cristina Glebova, via Unsplash)

Where Do Birds Migrate?

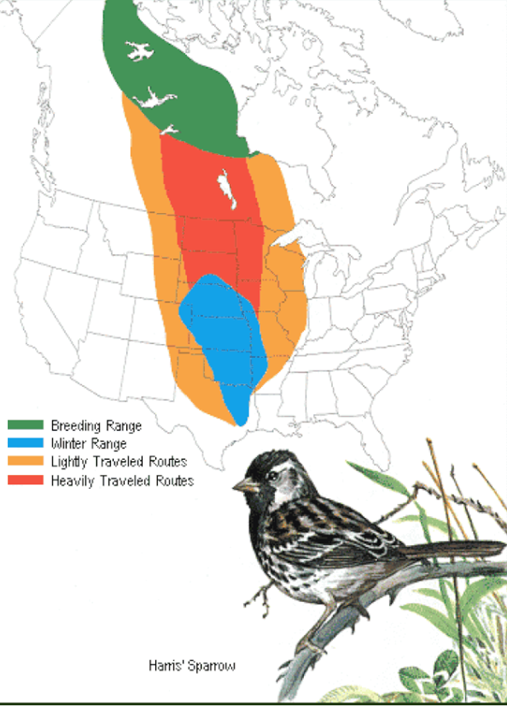

Migrating birds often take the same route each year. This leads to “super-flyways,” which, in North America, can be divided into four different sections: the Pacific, Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic Flyways. These distinct routes are used by many birds as they migrate.

Interestingly, Canada goose migration paths take them along all four of these major flyways as they migrate from Canada south to the United States for the winter, and back north for the summer. However, for a variety of reasons, some of these birds don’t always need to migrate.

Range of Harris's sparrow (Credit: U.S. Geological Survey, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Hardships of Migration

Although migration is necessary for many species of birds, it can be incredibly dangerous. Regardless of whether they migrate during night or day, smaller birds are especially vulnerable to predators. Owls, hawks, eagles, and falcons – who need to eat too – are merciless in their attacks upon migrating prey.

For birds that opt to travel at night, light pollution can pose a serious hazard. The artificial glow rising from cities and highways can interfere with the light from the Moon and stars birds rely on for navigation. As a result, they may become disoriented and be knocked off their migratory routes.

Another significant danger is the built environment. Hundreds of millions of birds each year are killed from crashing into buildings. Nighttime migrators may be attracted to the light that is emitted by the buildings, causing these deadly collisions. Daytime migrators are also impacted, often because they mistake the reflections of windows with the open sky.

Migrating birds against the Moon (cropped) (Credit: Ramiro Pianarosa, via Unsplash)

We humans are responsible for yet another serious threat to migrating birds: climate change. The effects of shifting temperatures make it difficult for birds to sense appropriate departure times for migration. Consequently, many birds returning in spring miss out on prime nesting conditions, leaving them to scramble for spots and limiting their ability to reproduce sustainably.

Droughts caused by climate change also pose mortal challenges to migratory birds, who face the risk of dehydration and death as a result. There is even evidence that body size and shape of birds are beginning to change as temperatures rise. It is believed that some birds are getting smaller as an adaptation to higher temperatures, and their wings are growing longer so that they can fly longer distances while expending less energy.

Want to Learn More About Migrating Birds?

No doubt, we still have much to learn about the fascinating elements and challenges of birds’ migrations patterns. For a deeper dive, check out MagellanTV’s documentary “Migrating Birds: Scouts of Distant Worlds.”

Ω

Maggie Williard is a contributing writer for MagellanTV. She recently graduated from Kenyon College, where she studied biology. She works in public relations and lives in New Jersey.

Title image: Sandhill cranes against a cloudy sky (Credit: Chris Briggs, via Unsplash.)