While climate change rapidly alters the world around us, one of North America’s most influential landforms stands as a beacon of both natural and human history. The Great Continental Divide creates two drainage basins but unites the continent in one shared geography.

◊

So often it is the case that human beings focus on what separates us. If we took a moment to appreciate the earth we walk upon, it would seem that what divides us is also what keeps us together. A striking natural example of this is the Continental Divide that separates the western regions of North America from those to the east.

Continental divides are natural markers delineating how precipitation flows onto land. They create pockets on which snow might build, establishing the flow of rivers and streams. Every continent has a divide except for Antarctica, which does not receive enough precipitation to flow toward a drainage basin.

The North American continent has six divides that direct water down mountain ranges into the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic oceans. The largest and most influential divide is known as the Great Continental Divide (although most of us refer to it simply as the Continental Divide). This drainage barrier plays a significant role in determining meteorological patterns and defining ecosystems across the continent. It has played an integral role in the continent's topography and the cultures of the people who have lived on it. And it's a magnet for visitors, as parts of it are located within Glacier, Yellowstone, and Rocky Mountain national parks.

(Source: Pfly, via Wikimedia Commons)

Against the Background of Human and Natural History

The question of nature versus nurture usually focuses on the balance between biological and social influences on a person’s development, but one could also apply it in thinking about the relation between mankind and “Mother Earth.” The geological state of nature has informed human behaviors for millennia. As our technologies and energy consumption habits have evolved, now the question is being asked, “How does human behavior affect the geological makeup of the planet?” Perhaps we can extend the nature/nurture dichotomy when considering how nature itself has evolved over time – both of its own accord and at the hands of human beings.

For millions of years, nature reigned supreme over humans, our migratory patterns and life expectancies responding directly to the ebb and flow of nature’s cycles. While natural and social scientists have long explored how human actions have responded to the resources at their disposal, new terminology reflects a shift in how the nature/nurture dynamic is playing out between people and the planet.

The term ‘anthropocene’ has recently entered into some geologists’ vocabulary, defining the current moment in Earth’s geology as marked by the influence of human activity. While natural evolution gave rise to humanity as we know it today, some scientists are starting to explore the possibility that our behavior is now altering the makeup of nature itself.

For more on the dazzling and important features of North America's national parks, check out the MagellanTV series America From Above - The West.

The Backbone of North America

To understand how we interact with nature today, scientists look back to the origins of geological formations to track migration and evolution. According to the plate tectonic theory, the Earth’s crust consists of seven major continental plates that rub against each other. The movements of these plates cause earthquakes, spur volcanic activity, and create mountain ranges when two plates collide. The Great Continental Divide traversing North America from Canada south through Mexico into South America is the result of a small tectonic plate that was subducted under the North American plate approximately 70 million years ago.

The tallest peak on the Continental Divide is Grays Peak at an elevation of 14,270 ft. While it towers over the rest of the divide, Grays Peak is only the ninth tallest peak in Colorado.

Running from Alaska all the way down to the Andes Mountains, the Great Continental Divide supplies water to the Colorado and Columbia rivers to its west, and to the Rio Grande, Missouri, and Mississippi rivers to the east. Seismic activity that occurred tens of millions of years before humans even existed created the topographic framework that would define how we would go on to populate the continent using its resources.

Native Populations to the East and West

The first people to inhabit the sublime landscape around the Great Continental Divide were Indigenous peoples thousands of years ago. A trail established by the Zuni and Acoma tribes dotted a southern part of the ridge with stone bridges and directional cairns, both of which are still used today. As descendents of Europeans moved west across the prairies, the Blackfeet Nation was one of the first tribes to resettle in the more mountainous regions of Montana and southern Canada. The picturesque environment seeped its way into Blackfeet lore and became an integral part of the native peoples’ creation story. The Indigenous people in the region were trailblazers both in a literal sense and in a more spiritual way, as they appreciated the divide as a symbol of nature’s power.

Mount Oberlin in Glacier National Park. (Source: Public domain, via Glacier National Park.)

A ‘Discovery’ of the Divide

The Great Continental Divide has become part of the United States’ creation story, dating back to 1803 when President Thomas Jefferson purchased the land as a part of the Louisiana Territory. Spanning a huge region from the Mississippi River through Montana, this acquisition, which had been previously unexplored by American settlers, stood between the early United States and what some viewed as its “manifest destiny” of westward expansion.

Explorers Lewis and Clark embarked on an expedition to survey the region while looking for a water route to the Pacific Ocean. On August 12, 1805, the expedition breached the Lemhi Pass of the Continental Divide. While the journey failed to discover the hoped for water route to the West, the Lewis and Clark expedition was successful in providing a detailed look into the rich nature, geography, and cultures of the areas encircling the Continental Divide, which was now considered U.S. soil.

Preservation within National Parks

The Chinese Wall, Forest Service Northern Region from Missoula, Montana.

(Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the years following the Lewis and Clark expedition, many explorers, tradesmen, immigrant families, and Indigenous peoples found themselves crossing the treacherous terrain along the Continental Divide. Until the end of the 19th century, the region around the Continental Divide was treasured primarily for its profitability, especially when the Great Northern Railway expedited travel and shipping in Montana.

As the U.S. continued to expand, so did its efforts to preserve and protect the nation’s abundant beauty. In 1910, Glacier National Park became the tenth national park, protecting one million acres of forests, more than 700 lakes, and 25 active glaciers. Next to Glacier National Park lies the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, which protects a section of the divide. This pristine wilderness features limestone cliffs including the Chinese Wall, a jarring cliff face showcasing the geological history of the continent’s movements.

Two Halves of the Same Continent

Beyond dividing the flow of water toward either the Atlantic or Pacific oceans, the Continental Divide has become synonymous with the delineation between the East and the West in the American consciousness. European colonization originated along the East Coast in the 17th and 18th centuries, but many Americans in the 19th century risked their luck (and their lives) in the great unknown West.

Many new inhabitants west of the Divide discovered that the landscape differed drastically from that of the East Coast and the Midwest. Although technology and travel connect east and west today, their respective environments and cultures differ significantly. As extreme weather conditions alter life on both sides of the geographical aisle, the Continental Divide serves as a physical reminder of how changes to our environment affect daily life.

Changing Conditions on the Divide itself

A road crew clearing the Triple Arches avalanche on June 6, 2022. (Source: Glacier National Park)

Over the past few decades, visitors to Glacier National Park and the Continental Divide Trail have noticed rapidly changing weather patterns. In 2022, historic levels of flooding ripped through Yellowstone National Park, causing damage to trails, infrastructure, and homes. Glacier National Park also experienced an unprecedented batch of spring snow, and the threat of avalanches caused by summer temperatures slowed down plowing efforts. The latest opening ever for vehicles to cross Logan Pass on Going-to-the-Sun Road occurred in the 2022 season.

Living in the Shadow of Change

Beyond the formation itself, the ripple of climate change has affected water levels and weather patterns across the western part of North America. With a smaller snowpack than in years past, the flow of water down the Rockies toward the Pacific has caused a drought across many areas in the West. Unable to supply water for consumption, agriculture, or aesthetic purposes, lifestyles across half of the continental United States have had to adapt to rapid changes. Fluctuating weather conditions leave visitors and local residents in a quandary about future access to the Continental Divide, but that doesn’t deter thousands of people who flock to the area to experience its grandeur today. A bill that would fund the completion of the Continental Divide Trail by 2028 has been proposed in the hope that people will be able to enjoy the hike for years to come.

Why Does the Continental Divide Matter?

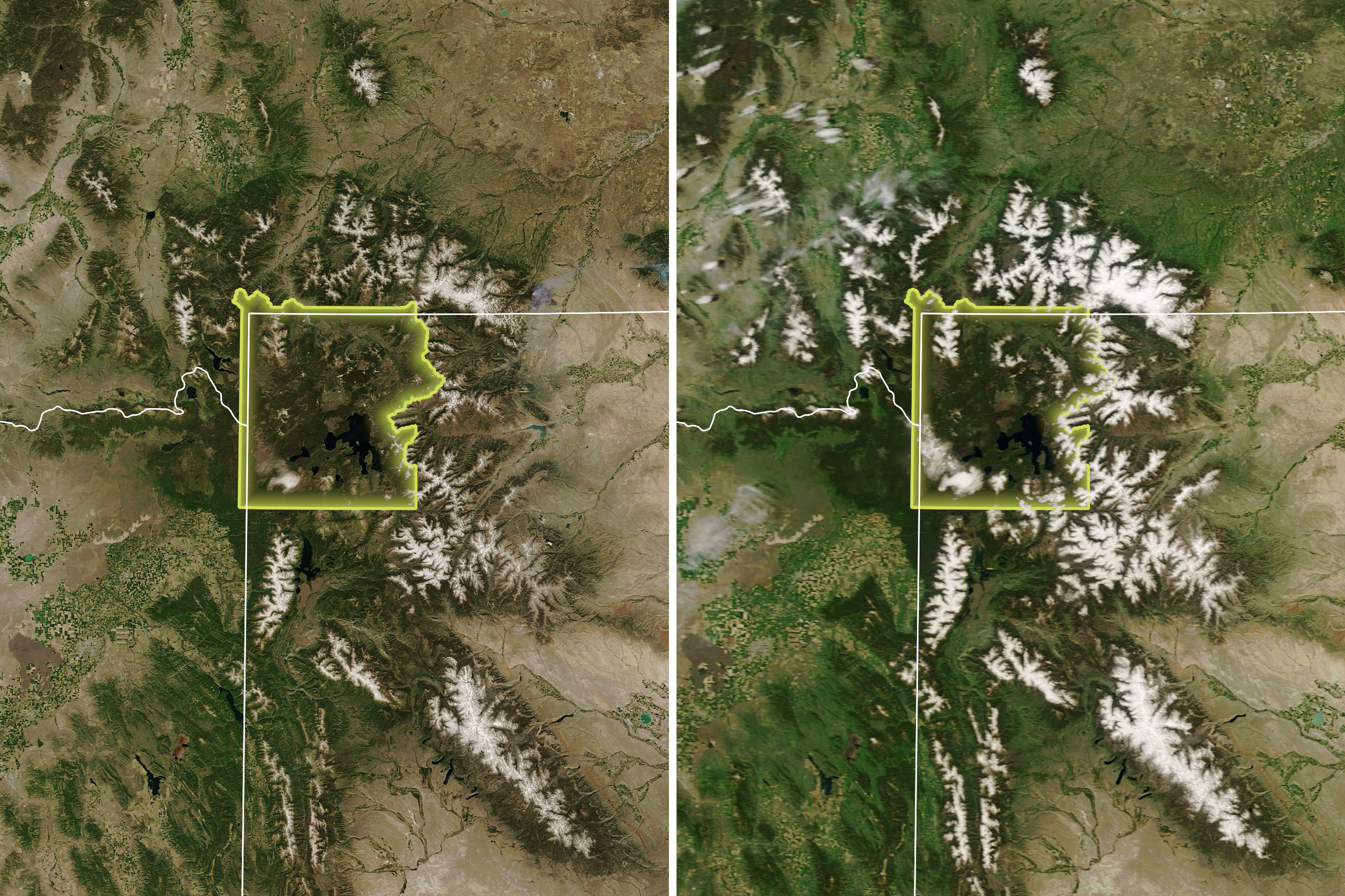

Satellite image of Yellowstone National Park June 16, 2021, compared with June 16, 2022.

(Source: NASA’s Earth Observatory)

The Great Continental Divide is a reminder of the massive, incomprehensible power that went into the formation of our planet. This geological feature defines North American nature, lifestyles, and culture. It draws our attention to the fragile relationship between our lives and the environments that support them. And it reminds us of the importance of National Parks in protecting the spaces that define us. As beneficiaries of a geography, history, and evolution that has until this point worked in our favor, perhaps it is time to consider how our own actions toward the planet carve out the future like water cascading down a continental divide.

Ω

Daisy Dow is a contributing writer for MagellanTV. She also writes for Local Life magazine. She recently graduated from Kenyon College with a bachelor's degree in Philosophy and Studio Art.

Title Image: Scenic view of the Lemhi Valley, Intermountain Forest Service, USDA Region 4 Photography.

(Source: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)