The Wright brothers were “first in flight,” but they were also ruthless in defense of their airplane designs. Did their business practices slow the progress of the American aircraft industry?

◊

When the Wright brothers had their amazing airborne day in late 1903, it may not have been apparent near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, that world history would soon be changed by this advance in flying stability.

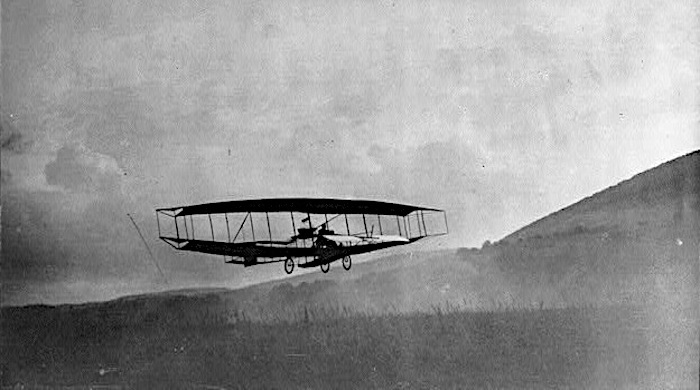

The Wright Brothers test-fly their aircraft on Fort Myer’s parade field. (Source: National Archives)

How did the brothers manage to steer their plane in a controlled, albeit brief, flight? They took into account the three main forces of air navigation and developed, or utilized, a solution for each element of uncontrolled rotation: roll, pitch, and yaw. For roll, in particular, they utilized a design called “wing-warping.” This was the only true Wright brothers innovation, but it was a significant one. The solutions to pitch and yaw were more or less off-the-shelf.

Who was the first of the brothers to fly successfully? It came down to a coin toss – and a bit of skill. Wilbur won, but his December 14 attempt was a bust. On October 17, Orville made the flight that has gone down as “first” in history books, though the brothers piloted two flights apiece that day.

Many inventors and would-be “aeronauts,” particularly in Europe and the States, had been working on “roll” and related problems for several decades. But as word spread among aviation enthusiasts, the secretive Wrights’ little-witnessed “first flight” was eventually accepted as the first successful demonstration of sustained heavier-than-air flight. It inspired a lot of adulation; it also inspired a lot of competitors.

The Wright Brothers and the Beginnings of the “Patent Wars”

Wilbur and Orville Wright, to their detriment, abhorred competition. Not only did they hate it, but they made a point of disparaging their competitors and would-be rivals as copyists and cheats. In 1906, the brothers took their design of the Wright Flyer, including its novel wing-stabilization feature, to the U.S. Patent Office. Their initial visit to the office was unsuccessful; the brothers had written the patent application themselves, and it was rejected.

However, their second attempt, made after they hired a patent law specialist, was accepted. The Wrights’ invention, wing-stabilization and all, had been officially declared new and unique – and, most importantly, protected against others using their invention without a license and compensation to the inventors.

Orville Wright soaring in his 1911 glider at Big Kill Devil Hill, October 24, 1911. (Source: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior)

But the brothers, who trusted themselves and very few others, interpreted their patent with a breadth that was stunning in its reach. Simply put, Orville and Wilbur believed that they had patented flight itself – rather than one element that made flight sustainable. They then took this belief and used it as a cudgel to beat down anyone who flew an airplane, designed or manufactured one, or even had the gall to participate in an air show. They held this belief in their hearts until their last days as businessmen.

Early U.S. aviation experimenter Gustave Whitehead is claimed by some to have beaten the Wrights into the air with a flight in 1901. Some are inclined to believe this claim, while others, including the Smithsonian Institution, where the Wright Flyer is displayed, consider the story to be without evidence. For more, view First Flight at MagellanTV.

Air Shows Provoke Retaliation from the Wright Brothers

In the early days of flight, air shows became all the rage in many parts of the world, from the U.S. to Brazil, and from Nova Scotia to Nuremberg. Thousands, even tens of thousands, of spectators would gather for these daring events, where aviators would fly their latest models in thrilling displays that gave them the name “daredevils.”

The Wright Brothers were aware of this, and they held to their position that every heavier-than-air plane in the sky violated their government-protected patent protection. So they began hustling aviators and aviation companies (mostly in the United States; European courts were more skeptical) to pay them royalties for every flight.

Remarkably, U.S. courts tended to agree with the Wrights, who had started to employ lawyers full-time to protect their patents. So, after a while, most companies paid off the brothers as a means of staying in business. Others simply slowed down production, or even closed up shop. The Wrights’ bullying tactics, similar to what we would call today “patent trolling,” often didn’t need, in fact, to go to court. Their efforts had a chilling effect on aviation, especially in the U.S. Not only did they keep some people out of the air entirely, but they also slowed down innovation and new designs.

The Driving Spirit of Glenn Curtiss, Inventor of the Curtiss Engine

Among early aviators, one stood out both in terms of attention and international stature, and this really piqued the Wright brothers’ ire. That flyer was Glenn Curtiss, whose innovative aeronautic designs got him noticed on both sides of the Atlantic.

Naturally, the attention Curtiss was receiving reached the ever-attentive ears and furrowed brows of the vigilant Wright Brothers. Curtiss flew with an alternative stabilization device that performed the same function as, but worked somewhat differently than, the Wrights’ “wing-warping” method of flaps and pulleys. The Curtiss innovation was called an aileron, which used alternating flaps along the trailing edges of wings to keep his plane stable laterally.

AEA June Bug (or Aerodrome #3) designed by Glenn Curtiss and built by the Aerial Experiment Association in 1908. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In the Wrights’ view, Curtiss’s design was insufficiently different from their own, so they promptly took Curtiss to court to demand a hefty licensing fee, plus damages. And they won!

But Curtiss he had been in this game for a long time, and wasn’t going anywhere. He had strategic skills of his own, as well as some deep-pocketed friends to help him. And, he was a bit of a hothead, a “flyboy” before such a term even existed – even as a child, he had a need for speed and the drive to keep going faster.

As a young teen, Curtiss had a bicycle that he constantly worked on, modifying it to be more aerodynamic and speedy. Eventually, he built his own bicycle, then moved on to motorbikes, and became an engine builder and motorcycle racer.

Glenn Curtiss and his Flying Machine

Curtiss clearly had a restless soul, but it was complemented by a clear focus and drive. And that got him noticed around his home state of New York, where, as a racer, he was declared the fastest rider in all of the state. He designed a racing motorcycle with an engine he built himself that became a reliable winner in the rough and tumble early days of the sport; he even set a new land speed record of 136 mph in a motorcycle race in 1903.

All these achievements drew the attention of Alexander Graham Bell, who was intrigued by the possibility of flight. In 1907, Bell initiated the Aerial Experiment Association to bring together the best minds in aviation and solve the issues preventing sustained, successful flights. Bell invited Curtiss to join the team, which was working in Nova Scotia on various experimental aircraft designs.

Though he’d had no direct experience in aviation, his engine-making expertise made Curtiss a natural for Bell’s team, and he excelled from the start. He quickly became expert in design and proved himself, despite his young age, to be a natural and charismatic leader who knew what he was talking about.

Glenn Curtiss in His Bi-Plane, July 4, 1908, gelatin silver print (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

It was a sign of Curtiss’s skill, expertise, and influence when Bell chose to move operations from Nova Scotia to Curtiss’s home in tiny Hammondsport, New York, to be closer to the younger man’s engine-building operations. From that time on, all the team’s tests utilized aircraft outfitted with one of the Curtis Motor Company’s engines.

Bell eventually lost interest in the less-than-successful results of his team’s experiments, but Curtiss barreled on. Eventually he designed an airplane called the June Bug, outfitted with ailerons, and flew it in a 1908 competition sponsored by Scientific American that he won. This brought him enough acclaim to come to the attention of the Wrights.

The Wright Brothers were specifically invited to participate in the Scientific American’s competition, but they refused, most likely due to an ongoing feud between the magazine and the brothers. Even so, they were incensed that the award and prize money went to Curtiss.

It was in the latter part of 1908 that the Wrights sprang into action, threatening Curtiss with legal action if he attempted either to fly or to sell his aileron-laden aircraft. They weren’t bluffing.

The Wright brothers proceeded to sue, and sue, and sue, claiming patent protection and demanding damages. And, time and again, they won. However, Curtiss did not have the personality to give in easily, and he challenged the lawsuits and, though he consistently received judgments against him, he was crafty enough to resist actually paying off what the court had ordered him to surrender.

And Curtiss was not alone in his problems with the Wrights. The situation became so dire that, by 1916, the brothers’ company was demanding that aircraft manufacturers had to pay them a royalty of 20 percent on every plane built in the U.S.

In the Run-up to WWI, the Feds – and FDR – Get Involved

Around the same time that the Wright brothers were suing everyone in sight, fears of the United States entering the war against Germany were growing, and the U.S. government was making early preparations for combat. Alarmingly, when the military started to investigate which airplane design would be most beneficial for their purposes, no American plane – and especially not the Wright Brothers’ now-outmoded designs – made the cut.

As a result, the U.S. military bought and flew only planes built in France at the beginning of America’s involvement in the Great War. And the nearly moribund American aircraft industry was further demoralized by being left out in the cold, even after Wilbur died in 1912 and Orville retired in 1915.

Franklin D. Roosevelt (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The national embarrassment could not stand, and so a task force under the control of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Delano Roosevelt took on the Wrights’ company and the industry that the brothers had both inspired and deflated. FDR was able to cajole the Wright company to agree to collaborate more freely with other manufacturers and, crucially, to share research and development, which they’d so jealously guarded until then.

Roosevelt guided the aircraft manufacturers into the formation of a patent pool that each company “bought into.” This allowed them to cross-license patents at the much-reduced rate of one percent! And the Wrights’ company agreed not only to do away with demanding licensing fees, but also to cease withholding licensing rights.

The End of the Patent War and the Beginning of a Golden Age

Arriving at this much-delayed resolution to more than a decade of acrimony substantially increased the velocity of innovation during this new time of collaboration. And the American aircraft industry, newly charged up in this progressive moment, moved forward quickly. U.S. companies eventually created aircraft that became the envy of the world, and they made up the ground that had been ceded to European manufacturers.

The change in approach resulted in so many new, successful designs that, beginning with the Roaring ’20s, it earned the sobriquet of the “Golden Age of Aviation,” with American industry leading the way. But what of the legacy of the Wright brothers?

It can’t be denied that Wilbur and Orville Wright justly deserved acclaim and admiration for their advances and innovations at the beginning of powered flight. But a cloud still shrouds the approbation due to the lasting damage of the Patent Wars – and the national embarrassment of American companies having been excluded from the list of military suppliers.

And what happened to proto-daredevil Curtiss? Well, his restless imagination, which drove him into airplanes, drove him out of the field – but not before actually merging his own company with his former tormentors’ to become the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, which exists to this day.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: Amalgamation of PD Images, Wilbur and Orville Wright, (Source: Wikimedia Commons)