Despite upheavals such as volcanoes, earthquakes, and tsunamis, the geological history of Earth has been relatively quiet over the past eon. We haven’t had, for example, a large asteroid impact or a supervolcano wipe nearly all life off Earth in many millions of years. (Knock wood, it could happen tomorrow. But so far, and certainly since the beginning of sentient life, things have been going pretty well for us here on our little planet.)

◊

Many believe that the development of life on Earth was virtually inevitable. However, seen through a lens of cataclysmic destruction and worldwide disaster, the odds that life would take root and thrive on this “third rock from the Sun” were mind-bendingly tiny.

Source: NASA, via Wikimedia

From small beginnings come great things, they say. Usually this maxim is applied to mundane activities such as building a business from a modest start-up into a profitable company with many employees. But let’s think of the old saying in the context of the cosmos: From an unimaginably miniscule and dense dot of something sprang the Big Bang and the universe we live in. Billions of years passed before our Solar System began to form, starting with gas and dust that coalesced into small clumps that, in turn, collected more more material to create larger objects.

Eventually, over 4.5 billion years ago, hard objects were drawn into a slow orbit around our developing Sun. Though myriad things could have gone wrong (and did), countless things went right. Small particles drifting in this rocky solar neighborhood knocked into each other frequently, causing larger particles to form. Large particles begat larger ones, and eventually, after 30 million years or so, masses of material held together by gravity and good fortune began to form rocky proto-planets.

The eon we’re in today is called the Phanerozoic, and it started about 541 mya, or “million years ago.” The era we’re in is the Cenozoic, which started about 66 mya. The period we inhabit is called the Quaternary, and that started off a mere 2.58 mya; and our epoch, which kicked off only 11,700 years ago, is called the Holocene.

Fiery Masses and Hot Lava Planets

Life was not even a whisper in that violent and unpredictable early period. The interaction of innumerable rocks and asteroids hitting the surface of proto-Earth caused the temperature of our small planetary body to shoot upward. Meteors shattered and melted on impact, eventually raising the temperature of Earth so high that its surface liquefied into lava at 2,000º degrees F. It sure wasn’t a likely place to find peaceful trees, meadows, and flowers for a little picnic, was it?

The good news was that we had a 2,000º planet floating around without an atmosphere in the deep freeze of outer space, which runs at negative 450º. Before too long (and by that I mean about a million years long), the surface of our planetary hellscape had frozen over, creating the Earth’s outer crust.

The first eon, which ran concurrent with the initial stirrings of our planet’s existence, is called the Hadean Eon, after Hades, the Greek god who reigned over the hellish underworld. It is an apt description of the fiery state of the early volcanic Earth’s sea of flames.

It Could Have Been Worse: Jupiter and Saturn to the Rescue

The pounding our Earth took over its first billion years didn’t suddenly stop altogether. It continued in the free-for-all that existed in solar space, with objects ranging from meteors to huge, sun-blocking asteroids raining down onto our planet.

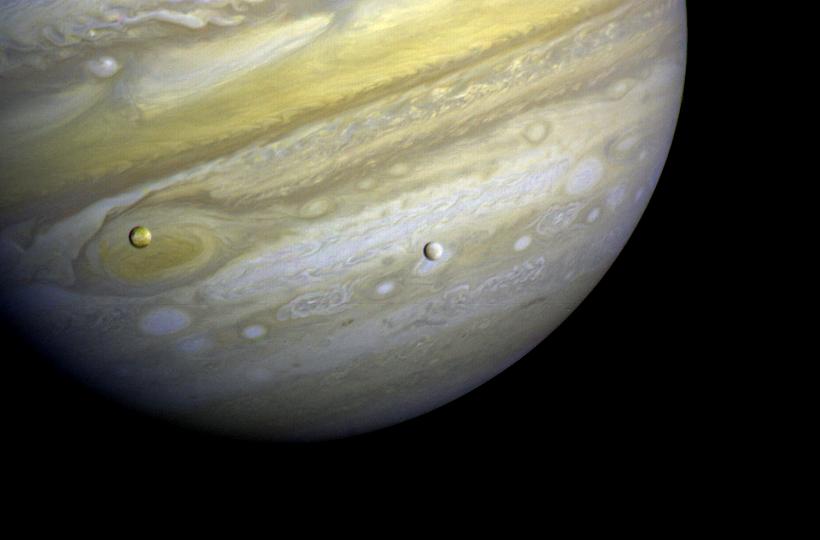

But it could have been worse. Much worse. Our future home could have been vaporized by the rocky debris floating around up there. Jupiter and Saturn helped stabilize the early Solar System by attracting, and thereby diverting, enormous frozen rocks that could have demolished Earth and its nearby rocky planets Venus and Mars. The enormous gas planets roamed through the early heavens, accreting (i.e., adding) many flying objects to their orbits, eventually causing Jupiter’s many moons to develop. Other potentially hazardous objects were tossed into the Sun.

Jupiter and its moons Io and Europa as imaged by Voyager 1 (Source: NASA, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

So let’s thank our “big brothers” in the Solar System, especially huge gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, for keeping us afloat and semi-protected as our planet’s natural processes started their development.

Earth’s atmosphere about 3.5 billion years ago was composed mainly of sulfur. While sulfur can support certain forms of life, it can’t support oxygen-breathing life. As cyanobacteria, which emitted oxygen, spread around the planet, the organisms that breathed sulfur died off and the Earth’s atmosphere became oxygen-rich.

About 100 million years after the planets started to form – or maybe “only” 10 million (we’re talking about enormous ranges of time here) – big, massively destructive impacts became less frequent, and the inner planets could calm down, find their orbital lanes, and tend to their own needs. For the most part.

A Mysterious Planet Nearly Destroys Earth, and Creates Our Moon

When we (we older folks, that is) were growing up, the standard story was that the Moon was the same age as Earth. Over time, with the assistance of our friend gravity, Earth pulled the Moon into orbit. The Moon, for its part, stayed at a respectful distance, regulated the tides, and let us know when a month had passed.

But stories change. Much of what we thought we knew about the origin of the Moon has turned out to be mistaken. It turns out that the Moon was almost entirely a part of the Earth that, like Adam’s rib, was extracted (or knocked off) to create the hovering mass above that lulls us to sleep.

A clip from The Jupiter Enigma

The new winning theory of the Moon’s origin is that an object the size of a small planet – the Mystery Orb, let’s call it – hit the surface of Earth at a glancing angle and, due to the size of the explosion, scorched everything on the planet. The impact was so violent that it sheared off a big slice and knocked it out into nearby space. After ruining Earth for another 10 million years or so, the debris steadied into orbit and eventually formed the satellite of lunar love we call the Moon.

It Came from Inside the Earth: Another Brush with Extinction

Let’s rush forward in time from billions to the merely millions of years ago on Planet Earth. The Moon has stabilized into a steady orbit, and the planet is rarely visited by disruptive asteroid collisions. Earth has been reconfigured by the lunar concussion, and a core of dense, heavy iron and nickel sits at the center of our spinning planet.

Life began on our planet about 3.5 billion years ago once the surface of the planet started to cool and harden. Photosynthesis in plants began somewhere in the vicinity of 2.8 billion years ago, adding oxygen to the atmosphere and making the environment more capable of fostering life. This allowed simple animal life to appear somewhere between 580 million and 890 million years ago.

So far, so good, but there’s also the little problem of a massive supervolcano that’s developing in the region we now call Siberia. For 50 million years (from approximately 300 million to 250 million years ago), the magma accumulating under the cap of the volcano heats up and churns ever more fiercely. When the pressure finally reaches a crescendo, the volcano erupts and blows hot ash and lava over a stunningly large area. Then the miasma of ash and debris is picked up by air currents and smothers the planet.

The Largest Volcano Ever

The volcanic cataclysm in Siberia was bigger than Krakatoa, which chilled the Earth for a year in the 19th century. In fact, it was most likely the largest volcanic eruption ever on Earth, lasting for close to a million years and leaving a band of ash in geological formations around the globe.

The devastation wrought by this event destroyed much of the life – simple reptiles and the like – that had evolved on Earth. The release of all that toxic gas provoked a climate disaster of almost unimaginable proportions, and the remains of the explosion, in an area now called the Siberian Traps rock plains, formed 720,000 cubic miles of basalt.

Source: Taro Taylor, via Wikimedia Commons

Methane and other gases in the air killed off oxygen, warmed the seas till they could not support life, and raised average temperatures on Earth by 10 to 20 degrees. Nearly every living thing on Earth became extinct. Fortunately for us, some life survived the Siberian eruption. Our distant ancestors – the earliest complex, multi-cell organisms – managed to eke out an existence successfully over time.

Chicxulub

There were numerous additional global cataclysms along the way. One of the most recent ones, relatively speaking (and probably the best known) was the one caused by a comet or asteroid that apparently created the Gulf of Mexico around 66 mya. As part of its long-term effect, it caused the end of the Cretaceous Period and took with it the massive species that populated the Earth at that time: dinosaurs and their ilk.

But your ancestors and mine survived that impact, called Chicxulub, and that’s sufficient reason for some celebration. This mass extinction event took out large animals and the ecology needed to support them. But enough life remained for the Cretaceous Period to be followed by a flowering of different life forms, including many mammals. The newly altered environment was repopulated by more adaptive, smaller species, particularly mammals. And among these new mammals were our direct ancestors, the first primates.

When the Chicxulub impactor hit, lava began erupting out of fissures on the other side of the planet, along the Indian peninsula. Though this compounded the collision’s effects for several thousand years, many surviving flora and fauna quickly adapted and spread.

In essence, we’re the PowerBall winners of the Chicxulub extinction. In a perverse way, we should probably be grateful the dinosaurs died. They opened up the real estate that we eventually came to dominate.

Lucky Us (for Now)

In the general scheme of things, it wasn’t likely that our planet would gather everything it needed to create life – water, amino acids, a relatively thin atmosphere with a nitrogen-oxygen mix instead of carbon dioxide – but it did. The haphazard development of Earth, lurching from disaster to calamity, punctuated by long passages of time when not much happened, is why we’re here today.

Source: Photo by Francesco Ungaro, via Pexels

If you can spare a moment, take stock of the basics of your life on this planet and acknowledge how circuitous and contingent the path to our existence has been. There are still many disasters that could befall us – some the size of an asteroid – but the fact that we exist means a lot of things went spectacularly right.

That’s not to say we couldn’t do some massive damage to this small, rocky planet upon which we depend for our very existence. We could, collectively, find ourselves drawn into nuclear conflicts that could quite plausibly spell disaster for the long-term health of Earth – in the form of nuclear winter – and for the survival of our species. Or humankind’s undeniable impact on global processes could send us over the climate cliff into widespread desertification, worldwide warming, and a disastrous rise in sea ocean levels.

But, for the moment, let’s put that discussion to the side and focus on the exceedingly small probability that we would even have evolved into Homo sapiens. As we’ve seen, eons of time passed before the first stirrings of life appeared here. And it was only through chance and sheer luck that life came to thrive on Earth.

We may not be able to keep it this way forever, so for now let’s recall the words of the great American comedian George Carlin. Pondering alarmist ideas about humans “hurting our planet,” he said, “The planet will be here for a long, long, long time after we’re gone. [It] will heal itself . . . ’cause that’s what it does.”

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Editor's note, July 2021: A callout in this article has been updated to reflect new findings concerning the dates for the appearance of animal life on Earth.

Title image: Earth at Night, North America by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio / Earth Observatory via Wikimedia Commons.