During the Cold War, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. competed in many geopolitical areas, one of which was the Space Race. Which superpower would be first to the Moon, and who would lead the charge? America’s indispensable man was Wernher von Braun, the brilliant rocket scientist. But von Braun had been indispensable, too, to Nazi Germany’s rocket program during the Second World War, and he could not entirely escape his past.

◊

The Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union was serious business. In fact, as an integral part of the Cold War that set in between the erstwhile allies of World War II, it was a no-holds-barred contest between the world’s two superpowers to determine who would get bragging rights to being “First in Space” – and first to land men on the Moon. And with that swagger would come the claim to technological and ideological superiority. The propaganda stakes were huge.

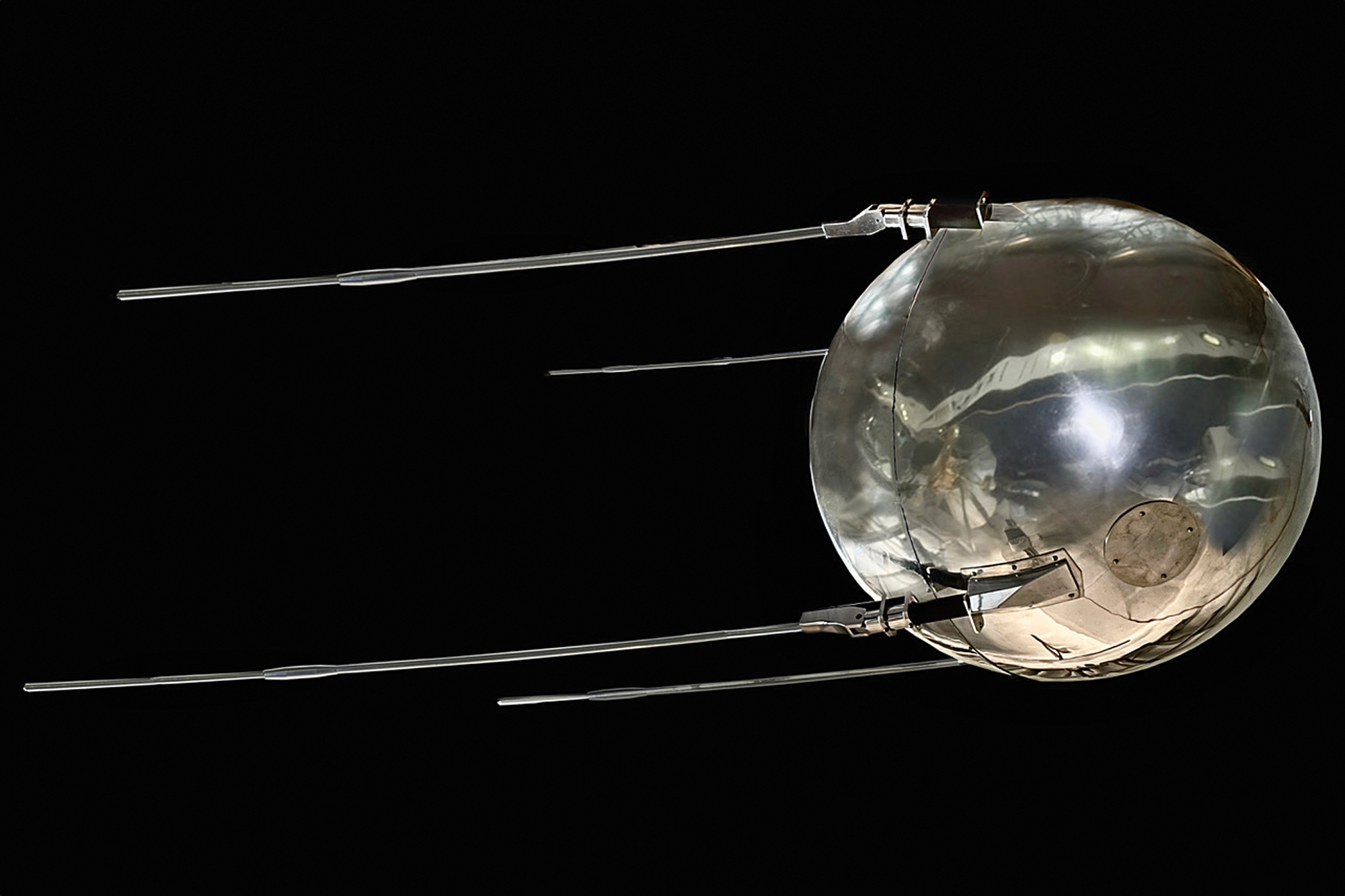

Sputnik mockup

(Image courtesy of Steve Jurvetson, via Wikimedia)

In this geopolitical boxing match, the first round went to the U.S.S.R. In October 1957, the Soviets placed the Sputnik 1 satellite into orbit around Earth. It was small, only about three times the diameter of a soccer ball, but large enough to be seen moving across America’s night sky by anyone with sharp eyes or a pair of binoculars. And it didn’t stay up there for long, less than three months, but its every orbit was like a raised middle finger to the U.S. space program.

Before we could sing a verse of “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” the Russians won another round when, later in 1957, they sent a dog named Laika into orbit in Sputnik 2. (Laika, alas, did not survive the trip.) The U.S. took round three with Explorer 1, its first orbiting satellite, on January 31, 1958.

After trading rounds over the next few years, the boxing match had become a race – the Space Race. And when President John F. Kennedy made his historic and inspiring speech at Rice University announcing the U.S. goal of landing men on the Moon, the race was on. Big time.

“We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.” – President John F. Kennedy, September 12, 1962

But to beat the pesky Russians in this high-stakes race, the Americans needed someone to design a rocket powerful enough to launch a crew of astronauts and all their equipment toward the Moon. And they had one. In fact, he’d been living in the U.S. and working for the military on rockets since the end of World War II. He was a visionary, a professor of physics, an engineer, a man with a noble German lineage and some distressingly inconvenient truths in his past. That man was Wernher von Braun.

Boyhood of a Space Race Dark Star: Von Braun’s Noble Roots

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun made his appearance on our little planet in 1912 in the town of Wyrzysk, in the Posen province of the German Empire (now Poland). He was the son of a conservative civil servant and his wife whose ancestry included many European royals. Wernher received the title “Freiherr,” which means Baron, although it didn’t really count for much after legal privileges of the German nobility were revoked following the First World War, in 1919. Did this combination of noble lineage and abrupt change in status affect Wernher’s outlook on his life and the lives of others? Perhaps..

Wernher wasn’t exactly a wunderkind, but he was smart and talented. At an early age, he set his sights on becoming a rocket scientist – and going to the Moon, literally. When he was 18, he met Auguste Piccard, the Swiss physicist, and, so the story goes, stated, “I plan on traveling to the Moon at some time.”

Wernher von Braun

(Image courtesy of NASA/MSFC, via Wikimedia)

But, in 1933, Adolph Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, and the Nazis took control of the government. For von Braun, the Moon would just have to wait. The Fatherland had other, less noble plans for him.

Von Braun: Forced Labor, and Rockets for the Reich

In modern photos, the village of Peenemünde looks like a lovely place. It sits by the River Peene on the German island of Usedom on the Baltic Sea. Great spot for a relaxing vacation. Who knows, maybe you could toss a line into the water and catch a fish of some kind. Or you could watch the ships go by on their way to Copenhagen or St. Petersburg – maybe even a warship or two. What, you might ask, could such a place have to do with the U.S.-Soviet Space Race? In a word: rockets.

When Wernher von Braun saw Peenemünde for the first time, in 1935, he apparently didn’t indulge himself in peaceful appreciation of the landscape and the shore. Rather, he realized that it could be the “perfect, secret place to develop and test rockets” for the Third Reich. By then, he had received his doctorate in physics and was working for the German Wehrmacht, although he had not yet enlisted in the military. It wasn’t long before he and his team were testing missiles of various shapes and sizes there. His crowning achievement was the revolutionary V-2 rocket, first tested successfully in the fall of 1942. Along with the world’s first cruise missile (the V-1 “buzz bomb”), the V-2 was one of Hitler’s dreaded “Vengeance” weapons, which the Führer counted on to snatch victory from defeat for Nazi Germany.

And where did these weapons come from? They were carried up to Peenemünde from an underground factory called the Mittelwerk where they were assembled by prisoners from Mittelbau-Dora, a subcamp of the infamous Buchenwald concentration camp. As many as 12,000 prisoners may have died building von Braun’s rockets, but they sure got the job done. A little messy, but how very convenient for von Braun and his team. How expedient.

Von Braun Makes His Deal with the Devil

Perhaps von Braun wasn’t particularly political in his outlook, or maybe his head was just too far up . . . well, too far up in the stars to care about such worldly matters, and besides, he didn’t join the Nationalist Socialist Party until 1937, by which time he made quite the impression on Nazi leaders. Of his decision to join the party, he wrote in an affidavit for the U.S. Army after the war, (quoted in Michael Neufeld’s book Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War):

In 1939, I was officially demanded to join the National Socialist Party. . . . The technical work carried out [at Peenemünde] had . . . attracted more and more attention in higher levels. Thus, my refusal to join the party would have meant that I would have to abandon the work of my life.

Actually, he applied for and was granted membership in the party in 1937, according to Neufeld, but let’s not quibble over the falsehood in a legal document. And let’s not split hairs about whether he voluntarily joined the Nazis or “was officially demanded to join.” Instead, let’s focus on the reason he offers for joining: to continue “the work of my life.” Again, how expedient.

But, you might think, at least he wasn’t a member of the SS, right? Well . . .

Three years later, it became expedient for von Braun to join the Allgemeine SS. After the war, in 1947, he explained to the U.S. War Department that he was advised by his superior and mentor, Walter Dornberger, “that if I wanted to continue our mutual work, I had no alternative but to join.” So, he became Unterstürmfuhrer [Lieutenant] Dr. Wernher von Braun.

Wernher von Braun and President Kennedy (Image courtesy of NASA, via Wikimedia)

Poor Wernher, he might have had to put aside his grandiose goals for a few years rather than becoming an SS officer, rather than benefiting from the forced labor of doomed prisoners from Mittelbau-Dora, rather than continuing to work on terror weapons for use against the civilians of London and other cities. After all, as he said (according to Neufeld), "I have very deep and sincere regrets for the victims of the V-2 rockets, but there were victims on both sides ... A war is a war, and when my country is at war, my duty is to help win that war."

And do you know what von Braun had to say years later about totalitarianism, when he was safe and sound and living the American dream in Alabama during the Jim Crow era? It’s short and easy to remember: He wrote in a 1952 magazine article that he “fared rather well under totalitarianism.”

Lucky Wernher.

V-2s Fall in a Torrent

The first V-2 exploded in the Chiswick district of London on September 8, 1945, killing three people. Said von Braun of his brain child’s success, the “rocket worked perfectly, except for landing on the wrong planet.” (Years later, Mort Sahl – the Jon Stewart of his day – mocked von Braun with a twisted version of the quote: “I aim at the stars, but sometimes I hit London.”)

A V-2 traveled faster than sound and hit its target without warning. It was the equivalent of a terrorist bomb exploding in a marketplace.

Of the 1,402 rockets aimed at England, 1,348 landed on London. In total, more than 3,000 V-2s were successfully launched against defenseless targets in the U.K., the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, killing many thousands of civilians and military personnel. The last one blew up the home of Mrs. Ivy Millichamp in Kent, on March 27, 1945.

The destruction of the V-2 explosion.

(Image courtesy of Wikimedia)

If he had been informed of Mrs. Millichamp’s untimely death, perhaps the ever-conscientious Dr. von Braun would have been inclined to send the Millichamp family a condolence note. But he was kind of preoccupied at that time with saving his own skin (along with about 500 of his colleagues from Peenemünde and the Mittelwerk). By the spring of 1945, von Braun realized the war was lost, and he was quietly maneuvering for the best chance to surrender to the British or Americans. The designer of his Führer’s Vengeance weapon clearly feared the vengeance that might await him should he be captured by the godless Red Army.

“We knew that we had created a new means of warfare, and the question as to . . . what victorious nation we were willing to entrust this brainchild of ours was a moral decision more than anything else. . . . and we felt that only by surrendering such a weapon to people who are guided by the Bible could such an assurance to the world be best secured.” – Wernher von Braun (on the CBS Biography television series)

His opportunity for salvation came a little later that spring, in Austria. According to Walter A. McDougall in his book The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Race, on May 2, von Braun, his brother Magnus, and a large contingent of his team came upon an American soldier to whom they surrendered. They were turned over to higher authorities for interrogation.

Wernher von Braun, the master of expedience, was coming to America. In time, he would resume his superhero role as the Indispensable Man, always aiming for the stars.

Von Braun: America’s Space Evangelist

Some years after settling in the U.S., von Braun decided to use the American press to promote space travel. From 1952 to 1954, he contributed a series of articles called “Man Will Conquer Space Soon!” to Collier’s, a popular weekly magazine of the time. Through the series (and other publications and interviews), he positioned himself as a sort of visionary space evangelist – and, not coincidentally, provided a self-serving portrait of himself as a patriotic German immigrant doing his duty for his adopted country. Eventually, some would call him the “Father of Space Travel.”

And it wasn’t all public relations. Telling the broad story of the Space Race would be impossible without featuring prominently Wernher von Braun’s undeniable contributions to the rocketry upon which the U.S. space program depended. As he had in Hitler’s Germany, he made himself indispensable. He was responsible for the design of the first largely successful U.S. rocket, the Redstone, which carried America’s first astronaut, Alan Shepherd, into space on May 5, 1961. It was also the first rocket to deliver a nuclear warhead in a live test.

And, when President Kennedy gave the go-ahead, von Braun had a big hand in designing the enormous rocket that would eventually launch Americans on their maiden voyage to the Moon.

Lift Off!

July 16, 1969: It was an ordinary Wednesday like so many others on Florida’s “Space Coast.” The sun was hot and bright, the winds light. A few puffy cumulus clouds drifted across the sky. But there was one difference: Men were about to head for the Moon, and a million or so people lined the coast to witness the historic event.

At 9:32 a.m., a giant Saturn V rocket (there’s that “V” again) lifted off from NASA’s soon-to-be-legendary Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A. Atop the rocket was Apollo 11, a small, two-part spacecraft carrying American astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Michael Collins. Their destination was the Sea of Tranquility on the Moon. Their reasons were not expedient.

Of the launch, American poet Louis Simpson wrote:

I saw the first men leave for the moon:

how the rocket clawed at the ground

at first, reluctant to lift;

how it rose, and climbed, and curved,

punching a round, black hole in a cloud.

Standing at a console in Mission Control that historic morning was a man in a white shirt and dark necktie, a man who had witnessed many rocket launches, a man with a thick German accent. He can be seen in video footage from the launch day, his face beaming with pride, for he knew that the United States, four days later, would declare victory in the Space Race. And he also knew, as many have testified, that it couldn’t have been done without him. He was the Indispensable Man. He was Wernher von Braun.