Jack London was the most famous and successful American writer of the early 20th century, earning a vast fortune writing books that are still read today. What’s far less known is that he was also a prolific and accomplished photographer who helped influence a reality-based aesthetic that soon defined American fine art photography.

◊

Toward the end of his South Pacific travel book, The Cruise of the Snark, the American writer Jack London relates a strange episode in which he, a very amateur dentist, pulls a bad molar from the jaw of an elderly resident of the Southern Pacific island of Nuku-Hiva.

A man of action first and foremost, London not only took pride in successfully extracting the tooth, he also made sure he was photographed doing so.

“On the veranda,” he relates in his book, “the light was not good – for snapshots, I mean.” Accompanied by his wife, Charmaine, and assistant Martin Johnson he sat the patient in a chair outdoors in strong daylight. “He complained about the sun,” London reported. “That was necessary for the photograph, and he had to stand it.”

Using forceps, London pulled the tooth easily enough, though too quickly for Johnson to get the shot. London was pleased to reenact the event. “I put the tooth back and pulled over. Martin snapped the camera. The deed was done.”

The photograph shows a standing London, in white shirt and pants, reaching into the open mouth of his seated patient surrounded by what appears to be jungle. It is just one of 106 photographs of people, boats, and landscapes that appeared in the pages of The Cruise of the Snark when it was published in 1911.

Because, as shown in the absorbing Magellan TV documentary Jack London: An American Adventure, by the time he set sail on the Snark voyage, the world-famous author had become an accomplished photographer. What’s more, his camera work made him an influential member of a group of San Francisco photographers who would, in the years following London’s early death in 1916, come to articulate a distinctly American brand of fine art photography, one based on the clear and unadorned expression of what was before the lens.

To learn more about the life and art of Jack London, watch MagellanTV's Jack London: An American Adventure.

A successful short story writer, London became wealthy and world-famous following the 1903 publication of his classic “dog book,” The Call of the Wild. He had overcome a quasi-criminal adolescence along the Oakland, California waterfront, and a dismal foray prospecting for gold in the Yukon, thanks to a largely self-directed education.

By age 20, London’s voluminous reading at Oakland's public library convinced him he could write short stories and novels, grounded in his hardscrabble life experiences, which were at least as good as what was appearing in high-end magazines. He was right.

London Was an Innovator of Early 20th Century New Media

By the turn of the 20th century, low-cost, full-color printing made possible a tidal wave of publications: newspapers, magazines, and books available to an avid reading public. This was a decade before movies, and 20 years before the advent of radio drew audiences to other forms of storytelling. It was the Internet of that era, and no writer benefited from the flashy new medium more than Jack London. Short stories, essays, and novels poured from his pen at a rate of 1,000 words a day.

In 1902, the 26-year-old author was in London, England, reporting on the squalid condition of the city’s poor dwelling in Whitechapel, the district made infamous by Jack the Ripper. Two years later, he was sent to Manchuria to report on the Russo-Japanese war. He carried a camera to document his experiences in both places, and his stark images of Whitechapel were published in his account of life there, The People of the Abyss (1903).

Destitute men line up for a free breakfast at a Whitechapel Salvation Army shelter, 1902.

(Credit: The Huntington Library)

London saw camera work as a way of getting larger fees from his magazine assignments. His hard-nosed attitude, however, does not account for the deft skill and sympathetic perspective he used to take pictures.

Presumably, he had learned the basics of photography from his first wife, Bess, who kept a darkroom. By then, the Eastman Kodak Company had turned what had been an arduous chemical and optical process involving plate glass negatives and bulky equipment into an efficient system of small, affordable, high-quality cameras and dependable, mass-produced roll film.

By 1903, he was a member of a small group of Bay Area photographers, led by the German émigré Arnold Genthe, who made images that emphasized the camera’s fundamental quality as a direct recording device. The San Franciscans’ art photography was grounded in expressing the thing itself. It was a reaction against the aesthetic prevailing back East and in Europe. There the vogue was for using special equipment and chemical processes to print an image to rival modes of Impressionist painting.

_-_(Moonlight_-_The_Pond)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Edward Steichen’s 1906 photograph "Moonlight – the Pond" is an exquisite example of the impressionist photography that London and his San Francisco colleagues rebelled against. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Getty Museum)

Genthe learned photography after coming to San Francisco in 1895 from his native Berlin to tutor the son of a relocated German nobleman. His portraits became popular with the city’s elite, soon making him a central member of the Bay Area art scene, where he befriended Jack London. Genthe’s documentary images of San Francisco’s Chinatown, the negatives of which he kept in a bank vault, were the only examples of his early work to survive the 1906 San Francisco earthquake that destroyed his studio.

Undaunted, Genthe set out to record the city’s devastation. His photographs remain gripping views of the ruined city. London, living in Oakland, reported on the disaster and also shot compelling photographs of the calamity’s aftermath.

London shot photos of the ongoing cleanup in San Francisco two weeks after the 1906 earthquake. (Credit: The Huntington Library)

Documenting with Pen and Camera the Voyage of the Snark

By 1907, when the 31-year-old London embarked on his proposed around-the-world cruise on the Snark, he owned two Kodak folding “pocket” roll film cameras, a large-format sheet film camera, one with a double lens to make 3-D stereo images, and another for panoramic shots. Accompanying him on the expedition was his second wife Charmaine, who carried a Kodak of her own, and his young assistant Martin Johnson, whose work filming incidents of the voyage (as well as capturing London’s turn at dentistry) was the first step in his becoming a pioneering documentary filmmaker.

London’s photographs lavishly illustrated his Whitechapel and Pacific Islands books as well as his reporting from Manchuria. But the length, breadth, and sophistication of his camera work was overlooked for nearly a century. As prodigious in shooting pictures as he was with his writing, approximately 12,000 of London’s negatives are archived at California’s Huntington Library. They sat mainly unappreciated there until a selection was published in a 2010 book.

The 19th-century worldwide colonial project was very much ongoing when London undertook his Pacific Ocean adventure. He was a believer in Social Darwinism and eugenics – two related, and ridiculous, notions popular at the time – that promoted racial hierarchies (with white Europeans at the top of a social development scale) along with the supposed necessity of clearing the human gene pool of “inferior” individuals.

Along with his racial prejudices, London was an avowed Socialist, a stance very much at odds with the vast wealth he earned, and spent, from his writing.

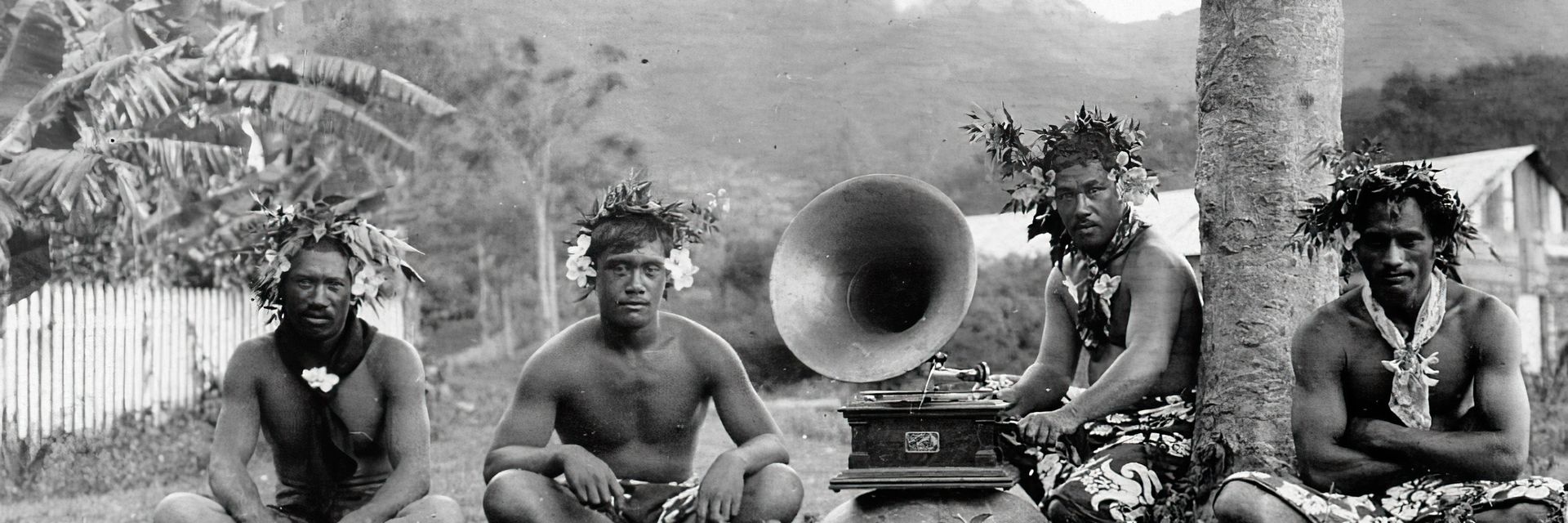

Ironically, London’s photographs reveal the finer side of his character. There is a presiding humane perspective in the pictures, a close-up interest in the destitute Londoners and South Sea Islanders (his callous treatment of his dental patient notwithstanding). This point-of-view is mostly missing from the camera surveys done by contemporary social reformers and world travelers who tended to emphasize a distinct and remote “otherness” to the people they photographed.

Natives of Nuku-Hiva posing with the gramophone London carried with him on the Snark. (Credit: The Huntington Library)

Avoiding any romanticization of his subjects, London’s photos have the same sense of unfussy storytelling that characterizes his books. He was obviously interested in “the thing itself,” with a fine feeling for lighting and subtle moments of action. His best photographs have a narrative heft that makes them fascinating documents and perceptive works of art.

Unfortunately, London’s world cruise ended in the Solomon Islands after 27 months. Beset by tropical fevers, London eventually contracted a case of the yaws, a horrific, potentially fatal skin infection that sent him to a hospital in Sydney for several weeks.

Back in California in July 1909, London’s physical decline came in tandem with personal tragedy. A newborn daughter died in 1910, and the lavish dream home on his California ranch was destroyed in a fire that same year. Acute alcoholism brought on kidney failure to accompany a host of other ailments including pleurisy and rheumatism. London was 40 when he died of uremic poisoning in November 1916.

Jack London’s Literary and Photographic Legacy

As the most successful American author of his era, London’s work remained astonishingly influential for the next three generations of writers: John Reed, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Jack Kerouac are in debt to his fiction and non-fiction writing, as well as to the example set by his rambling, daring, and alcoholic life. His major works are still in print.

We can speculate that had London lived longer, his photographs might have risen in prominence to equal the stature of his literary output. As it is, I submit that his art/documentary style proved as influential as his writing, but for a smaller and more obscure cadre of artists.

Though London’s friend Arnold Genthe moved to New York City in 1911, there remained a network of Bay Area art photographers who came to codify distinct rules for a photographic aesthetic based on crisply-focused, well-composed portraits, landscapes, and studies of material things.

By 1931, the cadre had a name, Group f/64, taken from the smallest lens aperture setting on a large-format view camera, that emphasized photographing aspects of the world without any special artistic embellishments or abstract meanings. This group, including Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham, was founded by the young San Franciscan Ansel Adams.

It is inconceivable that Adams, born in 1902 and growing up in a prominent San Francisco household, did not know of Jack London and his books. He may well have gotten his hands on a copy of The Cruise of the Snark, with its unadorned photographs of remote people and places, around the time he received his first camera, given to document a 1914 trip he made to Yosemite Park. If, in fact, London inspired the boy who would become one of the world’s most renowned photographers, just as he inspired some of the greatest American authors of the 20th century, he should be considered today as one of the most influential artists in history.

Ω

Contributing writer Joe Gioia is the author of The Guitar and the New World, a social history of American roots music. He lives in Livingston, Montana.

Title image: Natives of Nuku-Hiva posing with Jack London's Gramophone. (Credit: The Huntington Library)