The Dust Bowl of the 1930s was a Depression-era environmental disaster that decimated the livelihoods of American farmers. It also had a profound impact on culture and the arts. Could climate change cause its return?

◊

On Sunday, April 14, 1935, skies were blissfully clear over the Great Plains region of the United States. Dust storms had lasted for weeks, ravaging wheat crops, filling the air with particulates, and darkening the horizon. The pleasant weather that day was short-lived: By afternoon, a now-familiar tsunami of dust curled over the dry rural fields from Kansas to Texas. It would be one of the most devastating dust storms the area had experienced to date, and the day would forever be immortalized, earning the grim moniker of Black Sunday.

The impact of that storm and the ones preceding it would be far-reaching, destroying families’ livelihoods, impacting respiratory health, and leaving an indelible impression on the public consciousness, American culture, and history at large.

For some more examples of modern destructive dust storms, check out Dust Storm on MagellanTV.

A Perfect Storm: What Caused the Dust Bowl?

The term “Dust Bowl” was coined by Robert Geiger, a reporter for the Associated Press, who wrote: “Three little words, achingly familiar on a Western farmer’s tongue, rule life in the dust bowl of the continent – if it rains.”

The Dust Bowl was the result of complex environmental, socio-political, and economic factors. The zeitgeist of Manifest Destiny (a cultural perception that American settlers were ordained by God to expand to the Western reaches of North America), paired with federal land policies enacted following the Civil War, drew increasing numbers of prospective farmers to the Great Plains. The Homestead Act of 1862 offered American citizens 160 acres of surveyed government land to cultivate.

Heavy black clouds of dust rising over the Texas Panhandle, Texas, 1936. (Source: U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black & White Photographs, photographer Arthur Rothstein, via Wikimedia Commons)

A later amendment, the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909, further enticed farmers, both experienced and novice, to the region. At the time, it was common practice to remove beneficial endemic plants and grasses to plant wheat and corn, both of which were in increasing demand. These native plants were, in fact, crucial to sustaining a delicate ecological balance. The grasses grew readily with little rainfall, and their deep root systems served to hold the soil in place.

The removal of these native species, paired with record-breaking heat waves and drought beginning in 1930, resulted in the whittling away of the crops, thus exposing dry topsoil that was swept up by powerful winds, burying homes and businesses in mountains of dust. The Dust Bowl and its resulting economic devastation contributed significantly to a country already suffering from the impacts of the Great Depression.

By 1934, it was estimated that 35 million acres of once-fertile land were no longer viable for farming, and an additional 125 million acres had lost significant topsoil.

In his memoir, Farming the Dust Bowl, Kansas wheat farmer Lawrence Svobida movingly documented his life during the years of drought and choking dust. “When I knew that my crop was irrevocably gone I experienced a deathly feeling which, I hope, can affect a man only once in a lifetime. My dreams and ambitions had been flouted by nature, and my shattered ideals seemed gone forever,” he wrote.

World War II Recruitment Poster (detail), 1942. (Source: United States Office of War Information/United States National Archives, via Wikimedia Commons)

Breaking the Drought of the Great Depression

Rising to the occasion, the federal government worked to promote broader awareness of sustainable agricultural practices by establishing the Soil Conservation Service and Prairie States Forestry Project in 1935. Hammond Bennett, the first chief of the SCS (known as “the father of soil conservation”), heralded efforts to employ new farming techniques including crop rotation, strip farming, terracing, and more. Many farmers were resistant to change but were incentivized by the U.S. government with a payment of one dollar per acre if they utilized one of the recommended practices.

Despite pronounced efforts to assist farmers in recovery, the benefits of the reforms would be slow to dawn for many families. Caroline A. Henderson, who remained with her husband on their Oklahoma farm throughout the Dust Bowl years, wrote with eloquence and candor about the experience in letters to a friend in Maryland. The letters, published in a 1936 issue of The Atlantic, describe the toils of daily life and the pain of witnessing a cherished home become cloaked in dust.

“Wearing our shade hats with handkerchiefs tied over our faces and Vaseline in our nostrils, we have been trying to rescue our home from the accumulations of wind-blown dust which penetrates wherever air can go,” Henderson wrote. One letter voiced skepticism over claims that conditions were improving: “Printed articles or statements by journalists, railroad officials, and secretaries of small-town Chambers of Commerce have heralded too enthusiastically the return of prosperity to the drought region. And in our part of the country that is the one durable basis for any prosperity whatever. There is nothing else to build upon.”

Ultimately, it would require a number of forces to jumpstart the flailing economy, reverse the effects of decades of ecological mismanagement, and rekindle the hopes of farmers like Henderson. Efforts to combat widespread poverty and despair included President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s enactment of governmental reforms and work projects under the New Deal.

While the return of normal rainfall patterns and a gradual shift in agricultural practices were vitally important to ending the Dust Bowl phenomenon, it would take a historic event to fully revitalize the crippled economy: the onset of the Second World War. After the United States entered the war in 1941, new jobs in defense and the armed forces became available to men and, notably, to women as well. For those who fought (and safely returned) from the ravages of war, economic stabilization was one silver lining to the deadliest military conflict in history.

The Dust Bowl and the Arts

Among the most haunting visual depictions of the Dust Bowl are photographs taken by Dorothea Lange for the Farm Security Administration, a government agency that was created to assist farmers. In her most famed photograph, “Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California,” a matriarch flanked by her children looks past the camera, as if staring into the unceasing grayness of the arid plains. Lange described the circumstances behind the photograph: “I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. . . . She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding field and birds that the children killed.”

.jpg)

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, by Dorothea Lange, 1936. (Source: George Eastman House Collection, via Wikimedia)

While Lange’s images drew attention to the deep suffering of communities across the Great Plains, folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote about the Dust Bowl and the siren call of California for migrants. Guthrie recorded the album Dust Bowl Ballads in 1940. The song “Great Dust Storm Disaster” references Black Sunday: “On the 14th day of April of 1935 / There struck the worst of dust storms that ever filled the sky.”

In his 1943 autobiography, Guthrie wrote that “most of the people in the Dust Bowl talked about California. The reason they talked about California was that they’d seen all the pretty pictures about California and they’d heard all the pretty songs about California, and they had read all the handbills about coming to California and picking fruit. And these people naturally said, ‘Well, if this dust keeps on blowing the way it is, we’re gonna have to go somewhere.’”

.jpg)

First-edition dust jacket cover of The Grapes of Wrath (1939) by John Steinbeck. (Source: Jacket design by Elmer Hader, via Wikimedia Commons)

In John Steinbeck’s classic novel, The Grapes of Wrath, the author offers an account of the Joad family, Depression-era tenant farmers who make a journey from Oklahoma to California to escape the region’s devastation. The family anticipates a new beginning in California, along with abundant opportunities for employment. However, as many migrants discover, the promise of a new life often falls short of expectations. The influx of farmers to the California region results in job scarcity, giving self-serving landowners incentive to lower wages. The novel, anchored in the many realities faced by resettlers of the era, also examined the greed and inhumanity exposed as a result of such depletion of available resources.

Dearfield, Colorado: A Black Community Abandoned

While photographs and famed fictional narratives provide powerful testimonies to the human toll of the Depression and Dust Bowl, relatively little focus has been given to minority farmers and families impacted by the events. Beginning in 1910, the town of Dearfield, which was located east of Greeley, Colorado, became a bastion of opportunity for Black homesteaders seeking to escape oppression and the enforcement of Jim Crow laws.

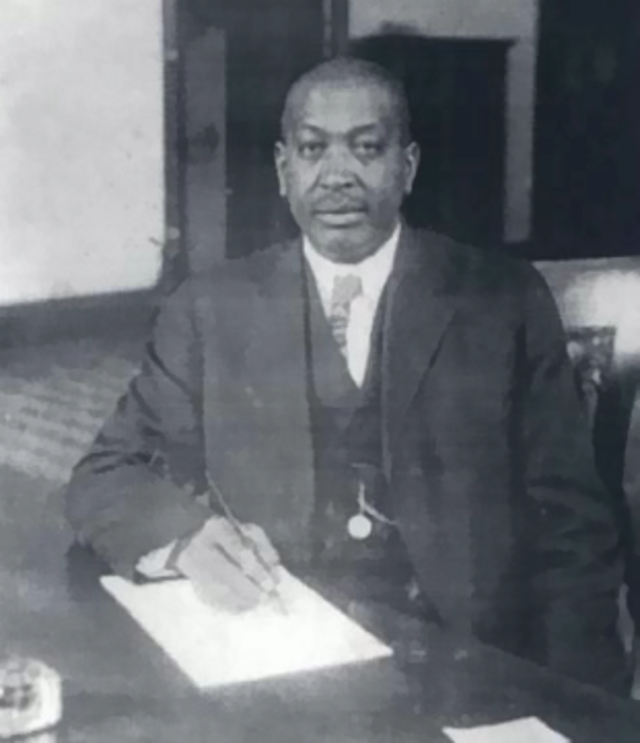

Oliver Toussaint Jackson, a businessman/entrepreneur from Ohio, was the founder of the Dearfield settlement. After applying for land through the Homestead Act, he was instrumental in both establishing the community and drawing prospective farming families to the region.

Oliver Toussaint Jackson, circa 1915 (Source: http://www.weldcounty150.org/HistoryofWeldCountyTowns/Dearfield.html, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the 1920s, prior to the Great Depression and Dust Bowl, Dearfield was home to some 700 residents, the majority of them Black. The town, which included a school, churches, shops, and a dance hall, subsisted on agriculture.

In an interview with NPR, George Junne, professor of Africana Studies at the University of Northern Colorado, called Dearfield “the most successful, best-known, African American farming community in the United States at the time.”

As the once-fertile land became diminished by drought, residents of Dearfield and other Black settlements relocated. Rather than trek further west to California, however, Black farmers and their families generally traveled north, with many Dearfield residents moving to Denver. By 1930, the once-vibrant and agriculturally rich community was home to a mere 25 residents.

The remains of Dearfield, Colo. (Source: Hustvedt, via Creative Commons)

Like many of the ghost towns of the high plains, little remains of Dearfield beyond a scattering of ramshackle buildings. But even these remnants serve as a reminder that casualties of the Dust Bowl included Black Americans eager for their own long-withheld access to prosperity and dignity.

Could Another Dust Bowl Happen?

Climate change, the thinning of the ozone layer, and the depletion of groundwater are all threats that may contribute significantly to future Dust Bowl–like conditions. According to climate.gov, “the Earth’s temperature has risen by an average of 0.14° Fahrenheit (0.08° Celsius) per decade since 1880, or about 2° F in total.” Additionally, the rate of warming since 1981 is occurring twice as fast as in previous decades.

Dust Storm, 4-14-35, Turtle Studio, Liberal, Kansas. (Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum, Public Domain)

The United States Department of Agriculture has identified a new “Dust Bowl Zone,” which includes areas in Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, and Kansas – regions that are especially susceptible to wind erosion. Additionally, since the year 2000, a drought has impacted the Western United States.

Variability is to be expected within weather patterns. Luckily, even amid record-breaking temperatures, wildfires, and overall drying trends in the American West, there have also been significant interludes of heavy precipitation, thus preventing the kind of sustained drought that occurred in the 1930s.

There’s no single solution that will prevent another Dust Bowl, but the lessons of the tragic events have led to valuable innovations. There have been significant advancements in land-use practices, including seeding and weeding and the use of irrigation, which allows farmers to draw water from underground aquifers, resulting in a general cooling effect.

The use of robotics in agriculture, including harvest automation, drones, and autonomous tractors, have made practices more efficient. But one approach to soil conservation is a simple, tried and true one. Considerable efforts are being made to restore native plants across the “Dust Bowl Zone” – resilient grasses with thirsty roots sure to grow verdantly – if, that is, it rains.

Ω

Matia Query is a freelance writer and the editor of BookLife, the indie author wing of Publishers Weekly. She lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.

Title Image: Dust storm approaching Stratford, Texas, 1935. (Source: NOAA George E. Marsh Album, via Wikimedia)

.jpg)