More than three decades ago, the United States and the U.S.S.R. nearly came to blows over a disabled Soviet space station called Salyut-7. Or did they? A new Russian movie mixes fact and fiction to tell the story, using historical assertions that may be indicative of a new Cold War.

◊

Remember the Cold War, that era of highly tense and guarded relations between the world’s two great superpowers? Now, raise your hand if you recall the Cold War–era saga of Salyut-7. It was a Soviet space station that went out of control, in 1985, as it orbited the Earth. Some believe that Salyut-7’s predicament might have pushed the two Cold War superpowers to the brink of war. Or at least that’s the thesis of a riveting and controversial Russian film based on events surrounding the near-disaster.

Produced by a consortium of Russian and international companies, the movie, eponymously titled Salyut-7, is the story of the Soviet space agency’s remarkable efforts to save the crippled space station before it could fall uncontrollably to Earth. It features a first-rate cast of Russian actors and state-of-the-art special effects that rival any seen in Hollywood movies.

When “Facts” Shade into Fiction

To a Western audience, the film is in striking ways reminiscent of Apollo 13, director Ron Howard's fact-based account of NASA’s ill-fated lunar mission that was forced to make a perilous return to Earth without successfully landing the third pair of American astronauts on the Moon. At the center of the Salyut-7 story are the heroic actions of the two cosmonauts assigned to the extraordinarily dangerous rescue mission. But the movie adds a spectacular Cold War twist to its tale: Not only does the mission race against the clock to prevent the out-of-control station from threatening populated areas below, but the cosmonauts must reoccupy and stabilize Salyut-7 before the U.S. space shuttle Challenger gets there to steal it.

Such a plot device may seem far-fetched, but is it really? And, even if so, would it be out of place, say, in an American film?

Of course not. The ratio of fact to fiction varies in films based on historical events and characters, but no “fact-based” movie is produced without making some stuff up. Viewers of Salyut-7 may find themselves flashing on Ice Station Zebra, a 1968 thriller starring Rock Hudson about the race between a U.S. submarine crew and Russian airborne troops to retrieve a top-secret American satellite capsule that had landed near the North Pole. A little digging reveals that the American movie is at least partially based on a real-life incident, but – and this is crucial – no one pretends that it is a historical drama.

“Star Wars” Alarms the “Evil Empire”

In the early 1980s, the Cold War was in full swing and the U.S.S.R. was going through a prolonged crisis of leadership. General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, who had ruled for longer than any Soviet leader except Stalin, was in ill health and died in 1982. He was replaced by Yuri Andropov, who lasted only two years before he, too, died. Andropov’s successor, Konstantin Chernenko, suffered from severe cardio-pulmonary ailments, and, in 1985, no one knew how long he would last.

From 1985 to 1990, Vladimir Putin was a KGB officer assigned to Dresden, East Germany.

Meanwhile, Ronald Reagan had been elected President of the United States. Reagan made no bones about his disdain for the Soviet system, labeling it “the Evil Empire” and setting upon a strategy to challenge the U.S.S.R. at every turn. Among his signature projects was the Strategic Defense Initiative, nicknamed “Star Wars,” which threatened to extend the military competition into outer space.

The Soviets were in trouble, and they knew it.

This was the context when disaster struck Salyut-7 in early 1985. The space station, which was unoccupied at the time, suddenly ceased communicating with its mission control team. Alarmingly, observations from land indicated that it was tumbling out of control. Although no lives were at stake, all the Soviets’ latest technology was incorporated into the orbiting station, and it was in danger of falling to Earth with no means to guide it to a harmless crash site.

Concern about the fate of Salyut-7 was not limited to the U.S.S.R. Other countries, including the United States, feared that a crash into a populated area could be catastrophic, especially if, as some speculated, the station was carrying nuclear devices. While the nuclear concerns, in retrospect, seem positively Strangelovian, don’t forget that the Cold War mindset was endlessly fertile when it came to suspicion of adversaries’ motives and capabilities – both in reality and in fantasy.

The Fear of U.S. Mischief – And a Legacy of Paranoia

One indisputable reality, of course, was that solving Salyut-7's predicament was primarily a Soviet responsibility. The movie’s version of events is plausible: Government officials debated whether to allow the station simply to crash, to shoot it down, or to attempt to save it. The mission sending two cosmonauts to dock with Salyut-7 did, in fact, happen and is at the heart of the film. As was the case with the astronauts of Apollo 13, the cosmonauts' ingenuity and courage were the very personification of the “right stuff.”

It would be easy to dismiss the film’s “space race within the Space Race” subplot concerning a Challenger space shuttle mission to steal the crippled station as reeking of Cold War paranoia. However, that doesn’t mean that the Soviet authorities of 1985 had no reason to be suspicious. After all, in 1974, the U.S. had, in reality, secretly raised a portion of the sunken Soviet submarine K-129 using a specially built ship called the Hughes Glomar Explorer.

The CIA spent more than $350 million building the Glomar Explorer, the ship that was used on the secret mission to raise the K-129. Ultimately the agency succeeded in recovering only about 40 feet of the submarine’s hull.

Whether a shuttle mission to abscond with Salyut-7 would even have been a practical possibility, though, is another matter altogether. As Bart Hendrickx persuasively argues in The Space Review, Challenger would not have been up to the task; and, in any case, his study of shuttle schedules, payloads, and technical limitations shows that a serious attempt to take possession of Salyut-7 was not in the cards. Among many problems with the scenario is that, although Challenger could have fit the space station into its cargo bay, Salyut-7 was much too heavy for the shuttle to have landed safely with it aboard.

Beneath the Veneer of a Cold War Thriller: Historical Facts and Fictions

So, why adulterate the gripping story of the rescue of Salyut-7 with a pile of easily debunked Cold War piffle? Well, to give the film Salyut-7 its due, the “race within a race” plot line adds a level of dramatic tension that engages viewers even more deeply in the story. This is, after all, a thriller, and what could be more exciting than a potential confrontation between the two great superpowers of the post-World War II era? Ask the producers of popular, nuclear freak-out movies such as The Bedford Incident, Fail Safe, and the classic Dr. Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

But another (and, in the real world, rather serious) factor may be at play here.

As Hendrickx points out, the immediate source for the Challenger mission plot line of Salyut-7 is a little known (in the West) so-called documentary produced for Russian TV called The Battle for Salyut: A Space Detective. Made by the usually well-respected studio of the Russian space agency in 2011, the TV show is essentially a propaganda film laying out the case for the supposed Challenger attempt to steal Salyut-7. And, according to Hendrickx, it collapses under scrutiny like an overbaked soufflé.

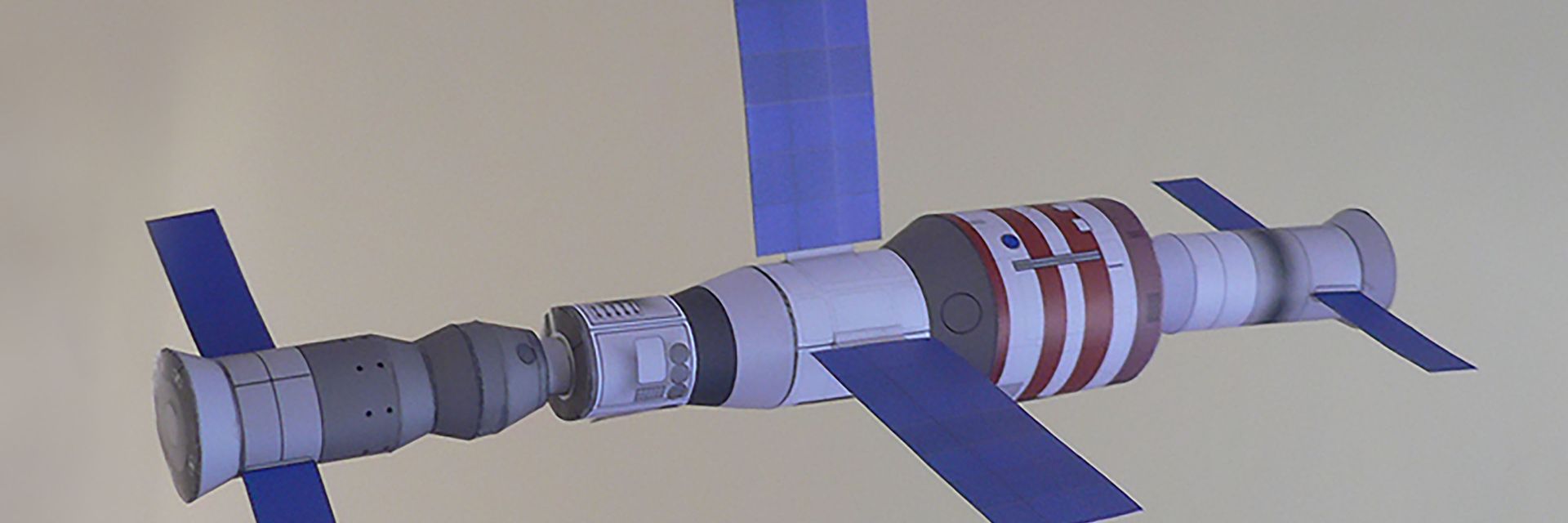

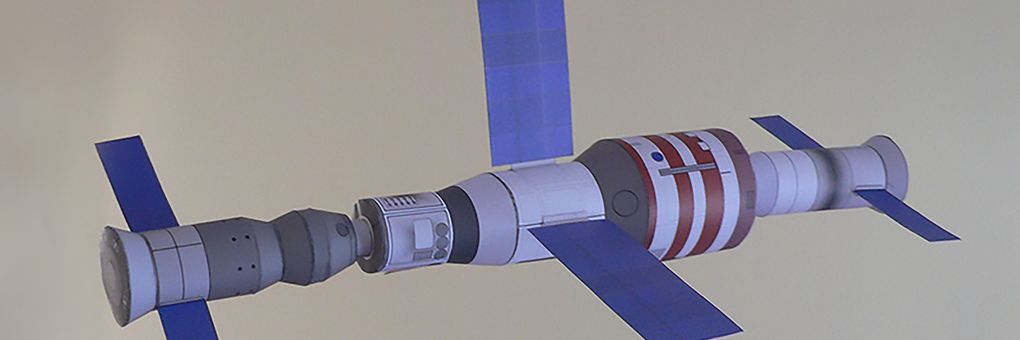

A model of the Salyut 7 space station, with a Soyuz spacecraft docked at the front port and a Progress spacecraft at the rear port. (Image courtesy of Don S. Montgomery, USN (Ret.), via Wikimedia)

A model of the Salyut 7 space station, with a Soyuz spacecraft docked at the front port and a Progress spacecraft at the rear port. (Image courtesy of Don S. Montgomery, USN (Ret.), via Wikimedia)

“Clearly, the main purpose of [The Battle for Salyut: A Space Detective] was to mislead an ignorant television audience into believing that the United States was willing to accept the risk of igniting a nuclear war by kidnapping a Soviet space station.” —Bart Hendrickx

Could it be that the Cold War mindset of the defunct Soviet Union – an ideologically driven, seemingly paranoiac suspicion of the motives and intentions of the Western European and American alliance – has persisted into the 21st century? And might the conflation of fact and fiction we see in Salyut-7 be symptomatic of that old mindset?

The New Cold War (Same as the Old Cold War?)

In the West, the story of the end of the Cold War can be summarized in several articles of faith: The Berlin Wall came tumbling down. The U.S.S.R. shattered into dozens of harmless pieces. Capitalism socked Communism in the kisser. We won, they lost. Hooray! It was the classic Hollywood happy ending – for us.

But for many Russians (including a young, up-and-coming KGB officer named Vladimir Putin), the break-up of the Soviet Union was an unmitigated tragedy. Gone was the treasured superpower status and the geopolitical swagger that came with it. Gone the “independent” Soviet republics and the Warsaw Pact buffer against NATO. Gone the proletariat paradise in which, as the saying went, ‘the workers pretended to work, and the state pretended to pay them.’

Perhaps both views were too simplistic. Maybe the period between the collapse of the Soviet Union, in 1991, and the recent reassertion of Russian power was actually analogous to the period of peace between the First and Second World Wars. What if the Cold War never truly ended?

After all, though the Russia that emerged after 1991 was smaller in area and population, severely weakened militarily and economically, and virtually without any serious diplomatic clout, it retained a massive stockpile of deliverable nuclear weapons, a fiercely patriotic populace, and a permanent seat (with veto power) on the U.N. Security Council. Did anyone with even a cursory knowledge of Russian history believe the country would become a bastion of liberal democracy? All that was necessary was the rise of a charismatic, determined (not to mention authoritarian and ruthless) leader – hello, Mr. Putin! Perhaps the bear was only hibernating – and now is reemerging into the warm spring air.

Palatable Propaganda or Harmless Movie Fun?

Seen in this light, Salyut-7 is not only an entertaining adventure film, but also a nifty piece of propaganda for an alternative Russian version of Cold War history: Not so fast, Mr. and Ms. NATO. We know what you were up to with your “Star Wars” and your “new world order.” You think we’re done? Not even close. How about a nice game of chess?

In the 21st century, Russia has traded its rusty old communist ideology for a shiny new authoritarian oligarchy (or kleptocracy, as many critics say). As capo di tutti capi, Putin deploys chess pieces with goofy monikers like Guccifer 2.0 and Cozy Bear to make mischief in social media and the nether regions of cyberspace to undermine Western democracies. And if caught, say, settling old scores with radioactive polonium or an exclusively Russian nerve agent on the streets of London, then he takes a page from Lenny Bruce, who advised spouses caught cheating in flagrante delicto to deny, deny, deny.

But, as Putin himself likes to say with a shrug, so what? If Salyut-7 incorporates some old Cold War propaganda to advance a new Cold War agenda, well, so it goes. The movie is still, in many respects, just a good old-fashioned space thriller. It’s fast-paced, engaging, a little scary, and fun. And, as in myriad movies before, stuff happens on screen that can’t be done in real life. So, trust the drama but verify the facts. And enjoy the movie for the thrilling and (mostly) true story of the cosmonauts it portrays.

Ω

Arthur M. Marx is Articles Editor at MagellanTV. He was previously a senior writer/editor at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government. He lives in Sarasota, Florida.

Title image: Paper model of Salyut 7 soviet space station with manned Soyuz craft and cargo Progress craft docked. (Credit: Godai, via Wikimedia Commons)

Editor's Note: Salyut-7 is no longer available on MagellanTV.