Though tea is usually thought of as the most ritualistic of beverages, coffee is actually inextricably tied to religion. While many legends suggest that the first cup of joe was brewed by a variety of priests and wandering shepherds in Ethiopia or Yemen, the first known coffee drinkers were actually Yemeni Sufi mystics who used coffee to stay awake during their long prayers. Due to its propensity for bringing people together, and because of the meditative nature of the brewing process, coffee also holds a prominent place in Christianity and even paganism.

◊

On many Sunday mornings in college, I would make my way down to a little cafe across the street from the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. Once there, I would order pastry and an iced coffee. After watching the milk swirl through the ice cubes, turning the dark liquid to a pale almond shade, I would write poetry and watch the day descend over the garden outside.

The cafe became something like a church to me during those times. It provided a necessary respite, a space to reflect on the past week and to consider the small things in life. Coffee was the center of the ritual, and in truth, ever since I started drinking it in high school, it has held a special place in my heart, symbolizing my decision to get up and be present each day.

Because of all this, I began to explore the connection between coffee and religion in history. As I discovered, the two have a long and storied relationship.

_-_23404782504.jpg)

(Credit: Pasi Mammela, via Wikimedia)

Sufi Mystics: The First Coffee Worshipers

Coffee plants existed around Africa and the Middle East for centuries, but for some reason, they survived the rise and fall of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages without anyone discovering how magical and delicious they could be when boiled. When at last coffee beans were recognized for their magical ability to generate an intoxicating drink, it happened in Yemen.

Though no one knows exactly who made the first coffee drink, it is known that around the 16th century, farmers of the region named the beverage qahwa, a term that means, essentially, “lessening someone’s desire for something,” and was the basis for the English words coffee and cafe.

Some of the earliest coffee drinkers on record were Sufi mystics in Yemen, who drank coffee in order to remain awake during their ceremonies, as well as to aid in their spiritual connection to God during sacred chants. The mystics loved coffee because it helped them stay awake for their evening “dhikr,” which was the process of chanting the name of God in rhythm for hours at night; in essence, it lessened their desire for sleep.

According to 16th century historian Abd Al-Qadir al-Jaziri, these mystics drank coffee “every Monday and Friday eve, putting it in a large vessel made of red clay. Their leader ladled it out with a small dipper and gave it to them to drink, passing it to the right, while they recited one of their usual formulas, ‘There is no God, but God, the Master, the Clear Reality.’”

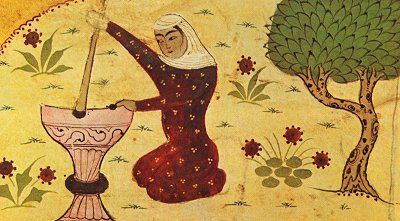

Depiction of Muslim saint and sufi mystic Rabi'a from a Persian dictionary (Source: Wikipedia)

Coffee was more than just a way to stay awake for the mystics. They also believed that when coffee was consumed with the correct sacred intent, it could catalyze the experience of “qahwat al-Sufiyya,” which can be loosely translated to mean “the enjoyment which the people of God feel in beholding the hidden mysteries and attaining the wonderful disclosures and the great revelations.”

According to Stephen Topik, during these rituals, “men and women together shared a common bowl that was passed around,” and “the initial objective of coffee-drinking was to transcend the material world and find peace.”

That sure sounds like how I felt at the Hungarian Pastry Shop on Sunday mornings. Something about the mixture of coffee and the grateful, reverential, and reflective mood I always found myself in at the time led to a new form of worship.

Coffee: Devil’s Liquid or Angel’s Cure?

Though coffee as a beverage emerged first in Islamic regions, soon enough it found itself on Islam’s list of banned substances. In the early 16th century, coffee’s prominence led to the appearance of coffee houses across the Middle East, from Cairo to Aleppo and Istanbul. These cafes’ proximity to religious centers – plus the kind of conversations and rowdy activities that were occurring within some of them – led some orthodox Muslims to ban the drink, on the basis that its effects were too similar to those of alcohol, which is forbidden in the Quran.

(Credit: Aaron Burden/Unsplash, via United Church of God)

Of course, coffee was also a problem in the eyes of the powerful, who were concerned that the cafes were often hotbeds of radicalizing and revolutionary discourse that took place over endless cups of the brew at all hours of the night.

By the 16th century, coffee was everywhere on the Arabian Peninsula, spreading to Egypt via the Yemeni port of Mocha. In the writings of that period, more and more legends began to crop up surrounding its origins, even several involving the angel Gabriel. One proposed that Gabriel suggested coffee as a cure for a Yemeni village’s plague; and another said that the angel brought coffee to earth to revive Mohammed the Prophet’s narcolepsy and flagging energies.

Coffee and Christianity: A Match Made in Heaven

Perhaps unsurprisingly, coffee has not always been approved by Christian authorities. In the 1500s, Christians – wary of the drink’s Islamic roots – began calling coffee “the devil’s drink,” preferring to stick to wine for their own rituals. Fortunately, after trying coffee for himself, Pope Clement VIII reportedly put an end to this practice with the comment, “Why, this Satan’s drink is so delicious that it would be a pity to let the infidels have exclusive use of it. We shall fool Satan by baptizing it and making it a truly Christian beverage.”

Coffee holds a special place at the core of modern day Christianity, as worshipers often gather in church basements to have coffee together. According to Jim Burklo, who discussed the relationship between coffee and church on the Huffington Post site, coffee is so ingrained in church culture that “the coffee hour [is] a permanent fixture of Christian orthodoxy.” These hours are special, Burklo writes, not only because they serve as hubs for church leaders to make plans and reflect on past events, but also because they’re separate from doctrine, instead intended to be places of community.

“Coffee hour does not force any political point of view on anyone; thus, in a time of radicalization of the pulpit, the social hall has become the true sanctuary of the church.” – Jim Burklo

And coffee hours are not limited to Christian churches: everyone from Gnostics to Unitarian Universalists regularly hold them. In essence, though it might not have a precise place in each of these faiths, coffee does serve as a way for people to come together, to form bonds, and to share stories – essentially encouraging a practice of community and love that is, arguably, the core point and purpose of many of these religions.

Witch’s Brew: Divination, Dream Symbolism, and More

Paganism predated Christianity and continues to inspire many of its modern traditions, and many writers have noted pagan elements that define the process of making coffee. According to beliefnet.com, the process of making coffee can easily be compared to a pagan ritual – there’s grinding the beans (crush wing of bat), steaming the milk (boil cauldron), add sugar (toss in eye of newt) and finally, the incantation: “How do you take it: milk, cream, sugar?”

Some modern pagans use coffee itself as an ingredient in their rituals. According to the pagan writer Lisa Wagoner, a coffee spell can be as simple as asking yourself while brewing, “What parts of you need stimulating and enlivening? What energy do you need to awaken? What aspects of the darkness will you most enjoy in this time? Pour yourself a cup of coffee and fix it to your taste.” For a more exacting ritual, she advises, “Stir your coffee clockwise before drinking and envision something nice happening before the end of the day. Stir widdershins (counter-clockwise) if you would like to ward off something negative.”

Some pagans also propose that coffee can be used for divination and for analyzing dream symbols. The process of predicting the future via the shape and arrangement of milk in coffee is called tasseomancy, and it proposes that different shapes can have different meanings; for example, seeing an airplane might indicate an upcoming trip, or seeing clouds could represent wishes coming true. Dreaming of coffee can also indicate a desire for change, or a break.

While these conclusions might be more related to the observer’s state of mind than actual revelation, the practices may still be interesting ways to examine your thoughts through an alternative medium.

The Quintessence of a Cappuccino: Coffee as Modern Alchemy

Though coffee has a strong presence in religious communities, for many of the 54% of Americans who drink it daily, it’s nothing more than a habit – an accidental ritual. If hyper-productivity is the religion of late capitalism, then coffee is its devotional rite.

But I prefer to think that drinking coffee is actually a way of slowing down amid the rush of modernity. The process of watching water drip down onto freshly crushed beans, balancing out the cream, and waiting for the brew to cool has always had a meditative effect on me – which may be why the specialty coffee worker and writer Liam Singer compares the barista’s task to alchemical rituals meant to prolong life through the ingestion of an elixir.

(Credit: Taner Soyler, via Pexels)

According to Singer, the ancient process of alchemy was actually a process of “death and rebirth...in the service of purification and eternal life, or union with the divine.” Aristotle, one of the earliest alchemists, proposed that alchemy was a process of cycling matter through the five elements: fire, water, air, earth, and another, called “quintessence,” or the “aether,” which composed heavenly bodies. Coffee – grown in the earth, dried and fermented in the air, distilled through heat, and poured into water for consumption – undergoes a physical change as it is consumed that can easily be compared to some alchemical practices.

And that final element, quintessence, has often been compared to the concepts of chi or gnosis, which describe a kind of life force or fundamental energy and essential aliveness, calling to mind that rush that most of us write off as jitters. But what if that rush is a kind of quintessence, an “injection of life-force itself,” as Singer writes? “If consciousness is believed to be a sacred gift, coffee’s effects are thus a direct communion with the divine,” he adds. Though all this might seem incompatible with our modern culture of rapidly gulping endless cups of poorly made coffee, if you start to delve into the specialty coffee industry – where practitioners have to undergo stunningly rigorous training in order to practice their craft – these connections begin to seem a bit more plausible.

Ultimately, though coffee may not prolong life and specialty coffee may be sinfully overpriced, deepening your appreciation for your morning coffee ritual – and the energy, community, or peace that accompanies it – might make the moments and days that comprise your life just that much richer.

Ω

Editor's Note: Due to a research error, a quotation mistakenly attributed to Jesus's Sermon on the Mount, along with the context around it, have been deleted from this article.

Title Image: A cup of coffee surrounded by coffee beans, photo by Zacharias Korsalka, via Wikimedia Commons.