Once the pinnacle of human development, the hot air balloon carried wingless creatures to new heights – literally and scientifically.

◊

Since human beings have told stories, we’ve told stories about flying. Flight implies freedom and being untethered to the geography of the planet – it’s the perfect foundation for larger-than-life tales of triumphs and tribulations. While real-life adventurers have actualized some of the most fantastical stories we have passed around about diving deep into the ocean or climbing above the clouds, it might feel like there is nothing left to discover on planet Earth.

Today we are all somewhat numb to the novelty of soaring at hundreds of miles per hour in commercial airliners above mountains and oceans. But flight did not come easily to mankind. To get to the present moment of double-decker airplanes and commercial space voyages, generations of engineers and adventurers risked their reputations and lives on outlandish inventions.

Hot air balloons may have been the first way to get people up into the air, but aviation has come a long way. Check out MagellanTV's History of Aviation.

The Early Stages of Human Flight

Long before people reclined in aisle rows watching movies at 30,000 feet, the sky belonged exclusively to insects. Four hundred million years ago, insects developed wings and 175 million years later, the first vertebrates followed suit. Humans, however, lack the specialized structures that make flight possible.

Without Frankenstein-style experiments and breeding programs, forcing our biological evolution towards flight would have been a long waiting game – and ethically questionable at best. While not exactly biological evolution, the fact that human beings went from being gravity-bound to space travel in less than 200 years is an adaptation unlike any other. It turns out the secret to human flight was less about having wings and more about the physics of the natural world.

Inspiration for Flight

Epic tales of flight inspired physicists and mathematicians to work backwards from stories of science fiction. The legend about Persia’s King Kai Kavus attaching eagles to the corners of a golden throne would require a lot of animal taming. The Greek myth about the inventor Daedalus and his son Icarus, who flew too close to the Sun, touched on the exhilaration of human flight but offered a sobering reminder about humanity’s limitations and the risk of our inventions.

“Kai Kavus Attempts to Fly to Heaven,” 15th century folio from a Shahnama (Persian Book of Kings). (Source: The Grinnell Collection, Bequest of William Milne Grinnell, 1920, The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Reminiscent of the structure of the hot air balloons that would enable humanity to take flight, the legend of Alexander the Great’s flying machine involved a basket chained to Griffins, mythological creatures with the bodies of lions and the heads of eagles. The creatures made flight feel fantastical but the idea of using something with an autonomous ability to fly to carry human beings felt achievable. With the fantastical ideas tabled, some of humanity’s greatest minds got to work trying to turn the stuff of legend into reality.

From Pie in the Sky to Glimmers of the Practical

Key pioneers of hot air balloon flight were the Chinese, who used sky lanterns as military signals around 200 BCE. The simple mechanics of a paper-covered bamboo structure meant that the heat from a small candle could lift the balloon into the air. About 300 years later, Hero of Alexandria (also known as Heron), a Greek mathematician and inventor, outlined instructions for the Aeolipile, a steam turbine composed of a hollow sphere mounted above a boiling cauldron. Tubes within the sphere supplied hot air, making it spin rapidly. These designs would inform the design of the bulbous, fabric-covered part of hot air balloons, which would be known to the industry as the envelope of the hot air balloon.

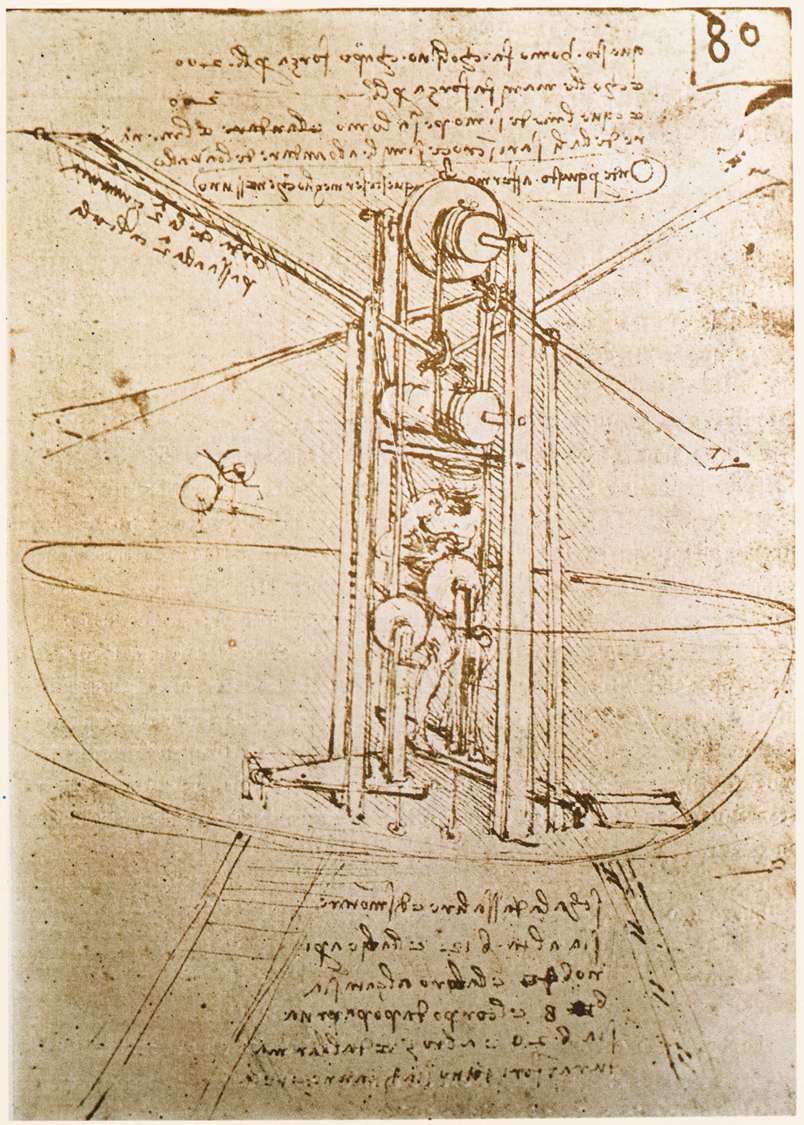

“Design for a Flying Machine” by Leonardo da Vinci (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Fast forward 1,100 years, and famed Renaissance man Leonardo da Vinci sketches many prototypes of the Ornithopter, a machine designed to emulate the flapping wings of a bird. While many of Leonardo’s inventions, including the parachute and the helical air screw, went on to be the basis of other forms of flight, the Ornithopter was too complicated. In fact, all it took was two brothers playing with paper bags in their fireplace to strike the right combination of chemistry and physics for human flight.

Hot Air Balloons Take Off

French brothers Joseph-Michel Montgolfier and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier often stared at clouds and talked about how curious it was that water vapor could be suspended mid-air. The two conducted at-home experiments fastening paper bags and seeing what could make them float. After unsuccessful attempts using steam and hydrogen gas to support silk paper bags, the brothers tried to make a taffeta envelope rise just using hot air. It was a success – and the start of something big. For a few years the two scaled up their experiments and performed public demonstrations with tethered balloons rising up a few feet before coming safely down.

Ascent of the Monsieur Bouclé’s Montgolfier Balloon in the Gardens of Aranjuez. Painting by Antonio Carnicero, c. 1784. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In September 1783, the brothers were invited to the grounds of Versailles to demonstrate their invention to King Louis XVI. To make the demonstration fit for a king, the Montgolfier brothers launched the first hot air balloon with living passengers onboard for an untethered flight into the sky. The envelope of the balloon was made of cotton canvas making the vehicle weigh a total of 400 kilograms. For fear of a mid-air accident, animals, rather than people, were loaded into the basket on the inaugural flight. Above a crowd of onlookers, the hot air balloon rose 600 meters into the air before a tear in the balloon brought the vehicle back to earth.

The sheep, duck, and cockerel that were passengers in the first hot air balloon flight were rewarded for their unwitting bravery in the skies with a place in the Menagerie at Versailles after their safe touchdown.

A Human Gets a Bird’s Eye-View

Just a few months later, in November of 1783, Jean-Francois Pilâtre de Rozier and Francois Laurent, Marquis of Arlanders, embarked on the first free-flight carrying human beings in a hot air balloon. Before traveling 5.5 miles in about 30 minutes, the balloon deflated a few times and popped at the seams. Despite the initial hiccups, the flight was a success and set the stage for air travel.

Physicists began experimenting with other types of gas, including hydrogen, to make balloons rise. Using a combination of sulfuric acid and iron filings, hydrogen gas eliminated the reliance on fires to get the balloon aloft, making longer flights possible. At one point, scientists experimented with balloons equipped with compartments for both hot air and hydrogen – which turned out to be an incredibly flammable and deadly design.

In 1785, French balloonist Jean-Pierre Blanchard and an American colleague, John Jeffries, successfully crossed the English Channel in a gas balloon. About half a century later, in 1836, balloonists made the long-distance journey from London to Germany – a notably long journey that would spark competitions to travel farther and farther in hot air and gas balloon travel.

More than a Leisure Mobile

One year after the first manned flight, the French Aerostatic Corps embraced the awesome power of hot air balloons to literally rise above the enemy and capture reconnaissance during the Battle of Fleurus. The ingenuity of the vehicle was unparalleled for capturing intel over a huge area, but as with all tools of warfare, a new device soon came to be designed specifically to shoot down hot air balloons.

During the Franco-Prussian War, particularly the Siege of Paris, 66 balloons were used to help civilians escape the carnage going on in and around the city. Over 100 passengers soared above the enemy to land in Germany. Additionally, hot air balloons were used to circumvent the dangers of travel by road to pass information between people. It is estimated that 11 tons of mail in the form of 2.5 million letters made a vertical escape from the enemy, all thanks to balloons. Hot air balloons would be used for a variety of purposes throughout the First and Second World Wars as well.

A Balloon Site, Coventry. Oil painting by Dame Laura Knight, 1943. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Extreme Side of Ballooning

Hot air balloons unleashed a worldwide fervor for flight. People were eager to set new records and be the first to do something incredible with the new power that balloon flight enabled. On the coattails of the hot air balloon came Orville and Wilbur Wright’s airplane – the first heavier-than-air machine to fly with passengers. Now, flight was split between two categories: airplanes and hot air balloons. In the early 20th century, people wanting to be pioneers of flight had to decide between refining the airplane or pushing the hot air balloon to its limits.

Fortunately, the Gordon Bennett Cup was established in 1906, formalizing ballooning as a sport. Named for an American newspaper publisher, the competition brought together the best minds and most adventurous spirits in ballooning. The goal of the contest was to see who could fly the furthest, safely, in a standardized design of a hot air balloon. In the first year, champion Frank Purdy Lahm flew for a record 22 hours and 15 minutes to a distance of 402 miles (647.1 kilometers). Today, flights take up to three days and see small teams of balloonists fly over 1,850 miles (approx. 3,000 kilometers).

The name “Gordon Bennett” is invoked as an expression of frustration or anger in parts of the United Kingdom. The idiom is a derivative of “gorblimey,” a shortening of “God blind me.”

Advent of Modern Ballooning

Time alone did not improve ballooning. To push the dial forward for a sport that seemed to be stagnating, some adventurers took great risks. Physicist Auguste Piccard and his assistant Paul Kipfer flew to an altitude of 51,793 feet (15.8 kilometers) in a metal cabin beneath a hydrogen-filled balloon to become the first human beings to reach the stratosphere in 1931. (Those two were lucky, especially as hydrogen had largely been abandoned for use in hot air balloons due to its flammability.) But if ballooning was going to catch on, something needed to change.

Ed Yost, known as the father of modern ballooning, fundamentally changed the design of hot air balloons in 1960 by using a propane burner to make hot air easier to harness. He used lightweight nylon for the balloon’s body and reworked the shape of the envelope. With a streamlined design and increased control of the balloon’s direction and height, the sky was the limit for the future of ballooning.

One of three balloonists from a failed Branson-led to circle the globe emerges from the crew’s capsule (Credit: U.S. Coast Guard, AMT2 Marc Alarcon, via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1987, Sir Richard Branson and adventurer Per Lindstad spent 31 hours and 41 minutes crossing 3,074 miles (4,947 kilometers) of the Atlantic Ocean from Maine to England in a hot air balloon. The envelope of the hot air balloon was the largest ever built at the time, holding approximately 2.29 million cubic feet (approx. 64.85 million cubic liters) of air. The feat revived an enthusiasm for ballooning, and people began to see it as an extreme, entertaining sport. By riding the Atlantic jet stream, Branson and Lindstad’s balloon reached speeds of 130 miles (209.2 kilometers) per hour.

A Race to the Top

A rapid fire of world records in the next few decades redefined the history of hot air balloons. The first circumnavigation of the globe (29,055 miles/46,764 kilometers in just under 20 days) took place in 1999; the first solo flight around the world (22,100 miles/35,566 kilometers in 13 days) happened in 2002; and the highest ever hot air balloon flight occurred in 2005 (69,852 feet/21.3 kilometers), which is still a record almost 20 years later.

(Credit: Ed Hathaway, via Pixabay)

The most recent records have been more about speed or novelty. The fastest solo balloon flight around the world took 11 days for Russian Fedor Konyukhov. The greatest mass hot air balloon ascent took place in 2019 at the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta when 524 balloons rose over the deserts of New Mexico. From supporting the highest slackline walk 6,236 feet (almost two kilometers) in the air to having daredevils stand on top of the envelope at 13,175 feet (just over four kilometers), hot air balloons offer a unique kind of tranquil stability that no airplane or drone could emulate.

While airplanes have beaten out hot air balloons as the go-to form of air travel, the lure of dangling from a basket suspended in mid-air still draws huge crowds. Hot air ballooning was born out of a curiosity to fly and made possible by countless dreamers, adventurers, and engineers who kept literally pushing the envelope to see how high and how fast hot air balloons could take people. Indeed, they rose to heights once imaginable only to the likes of Leonardo da Vinci, making the fantastical a part of everyday life.

Ω

Daisy Dow is a contributing writer for MagellanTV and freelancer. Originally from Georgia, she went to college to study philosophy and studio art. She now works in Chicago as a media relations coordinator.

Title Image credit: Pixabay