For at least the first 200 million years of its existence, the planet Venus thrived. Not unlike its nearest neighbor, Earth, Venus had oceans, a thick atmosphere, and a variety of elements that might have served as the building blocks for the beginnings of life. But then Venus’s destiny took a turn in a different direction. A combination of intense solar heat and a runaway greenhouse effect destroyed Venus’s chances to harbor life and turned Earth’s twin into an 800-degree hellscape.

◊

Venus, the second planet from the Sun, presents a singular figure in our sky. Brighter to us than any other object in the heavens, save for the Sun itself, it’s also our closest planetary neighbor, closer than Mars. And for hundreds of millions of years, Venus and Earth were virtually twins: They are approximately the same size, and, about 4.5 billion years ago, had many similar features.

Back then, the pull of gravity was similar on both planets. They had thick atmospheres made up of hydrogen, methane, nitrogen, ammonia, and, most importantly, plenty of water vapor. The surfeit of water vapor allowed the planets to heat up and retain energy from the Sun’s rays. Their landscapes held expansive oceans of liquid water and hundreds if not thousands of massive volcanoes all around the “twin” globes. And both featured mountain ranges, great basins, carbon dioxide in their atmospheres, and an interior core composed of liquid iron surrounded by a rocky mantle.

Learn more about "Earth's Twin" on MagellanTV's original documentary series, Exploring Venus.

So, then, why is so much current planetary exploration focused on Mars and not Venus? To answer that question, we have to reach back as far as 4.3 billion years into our past. Because while the Earth slowly developed an oxygen-rich environment that harbored early signs of life, things evolved in a much different direction for Venus. In essence, Venus burned itself to a crisp due to, among other factors, runaway greenhouse gas production. In fact, it’s now the hottest planet in our Solar System, hotter on its surface than even the Sun-hugging Mercury.

Hostile to Life: How Venus Turned

Despite the many similarities between early Venus and Earth – atmospheric, topographical, as well as compositional – it’s clear that the planets’ fates diverged a long time ago. This was due to some dramatic differences between the two worlds. Although our planets’ sizes are quite alike (Venus is 95 percent the size of Earth), our relative distances from the Sun mean that much more solar radiation makes it to the surface of Venus than to Earth. Venus’s distance to the Sun – 67.25 million miles – is 72 percent of the distance between the Sun and Earth, but Venus is bathed in 200 percent the amount of sunlight we have here on our home planet.

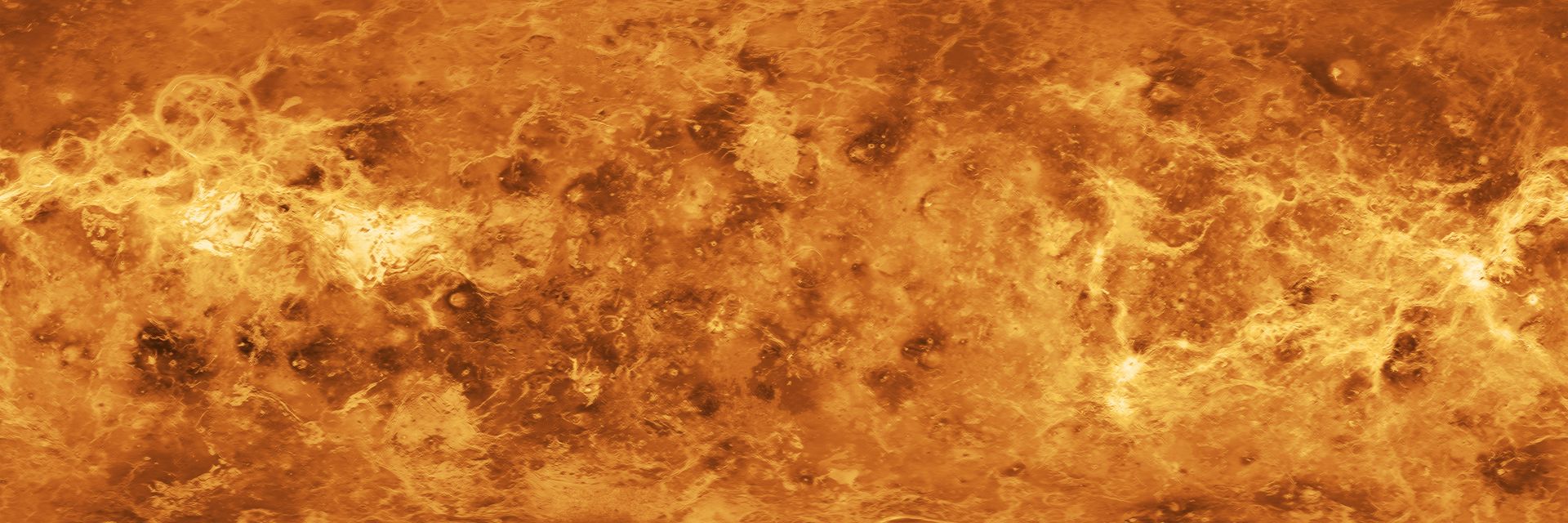

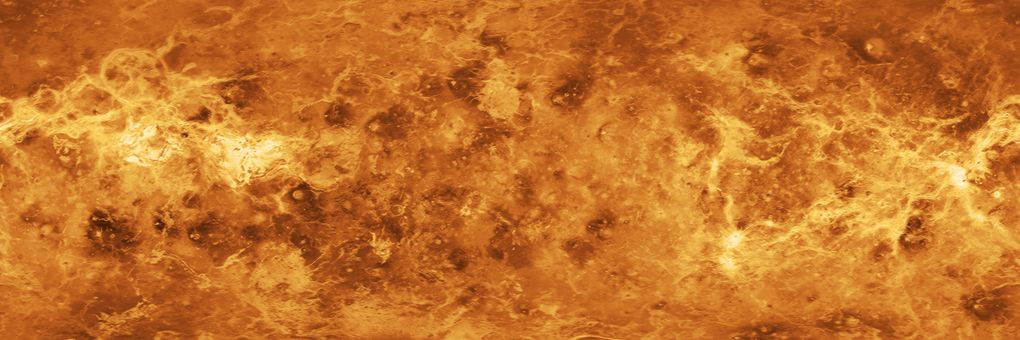

Artist’s rendering of the Venusian landscape, where temperatures regularly top 800 degrees Fahrenheit (Source: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center)

With all that energy reaching and being retained on the surface of Venus due to its thick atmosphere, the planet gradually heated up over hundreds of millions of years. As explored in the visually stunning MagellanTV’s original documentary Venus: Death of a Planet, the intense, relentless heat filtered through the atmosphere down to the oceans that covered much of the planet. Over time, the oceans began churning and eventually boiling, to the point that the oceans’ H2O evaporated, leaving behind water vapor and carbon dioxide.

Of the eight planets in the Solar System, only Venus and Uranus rotate counterclockwise. If you could stand on Venus, you’d see the Sun rise in the west and set in the east.

There is no evidence that Venus ever supported life. But, speculatively, had there been a period during which life emerged on Venus, any organisms would have been seared off the planet as its liquid water disappeared. The formerly water-rich planet evolved into the one we know now: a hellish world encircled by heavy, 30-mile-thick clouds of sulfuric acid that reflect light out to space as well as trap blast furnace–like levels of heat on the surface. How hot is it? At temperatures that reach well above 800 degrees Fahrenheit, even lead doesn’t stand a chance of remaining solid; it liquefies at slightly over 600 degrees.

Venus: A Truly Forbidding Planet

Although Venus and Earth may once have been “twins,” there are remarkable differences. For example, the Earth rotates on its axis once every 24 hours, determining our day; Venus takes 243 of our days to make one full rotation. And the planet’s day is even longer than its year; it revolves around the Sun once approximately every 225 Earth days. This means that, if you were on the sunny side of the planet at dawn, it would be a long wait until dusk – as long as seven-and-a-half Earth months!

Venus’s planetary tilt is a mere three percent, making it appear nearly upright as it travels around the Sun. By comparison, Earth’s tilt is a much more pronounced 23 percent, which allows for seasons and promotes and supports the existence of life. The lack of a significant axial tilt on Venus means there are no seasons, and there’s negligible variation in atmospheric conditions and temperature from pole to equator. If you like summer heat – well, if you like lead-boiling heat – maybe you’d find a week on the surface of Venus to your liking.

There could be a better way to visit. Check out MagellanTV's original companion documentary, Cloud Cities of Venus, for a discussion about how we might, some day, live in the clouds of Venus.

These factors are why so much more interplanetary investigation is being directed toward Mars than Venus. Though the surface of Mars is definitely forbidding, its high temperature is about 70 degrees Fahrenheit, making it much more human-friendly than the scorching surface of Venus.

Venus’s Volcanoes: A Reason for the Planet’s Vaporization?

Venus has the heaviest atmosphere of any rocky planet, and one of the driest. The Sun’s ultraviolet rays created an oven-like heat that left the atmosphere filled with ozone. And literally tens of thousands of volcanoes have added sulfur dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, and carbon dioxide, gases that are inimical to life and promote a runaway greenhouse effect.

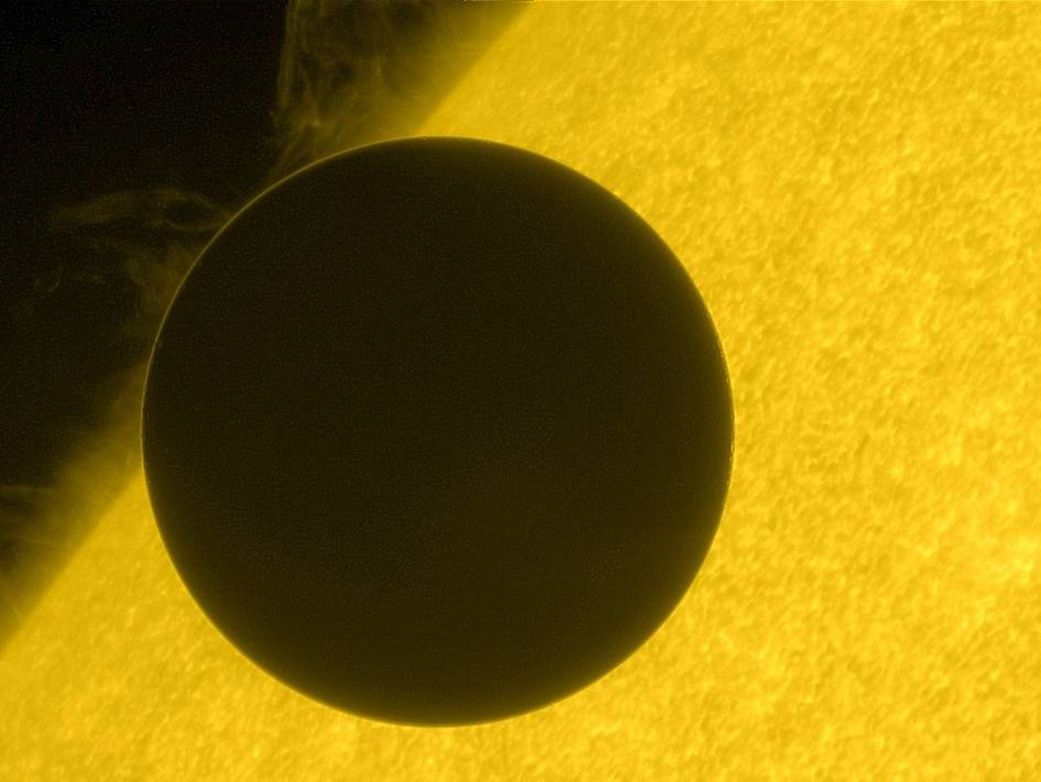

Venus makes a rare appearance transiting the Sun, visible from Earth. (Source: JAXA/NASA/Hinode)

The volcanoes dot the surface of the planet, from sizes too small for visiting spacecraft to count to gargantuan shield volcanoes just like those on Earth. Researchers have counted 1,600 distinct “mega-volcanoes,” and even more smaller ones. The larger, mountainous ones have been measured at sizes up to 150 miles wide, with lava flows that run up to 3,000 miles long. The plains created by the flows cover a full 80 percent of the planet’s surface.

What is a runaway greenhouse effect? Simply put, it’s when certain gases – primarily carbon dioxide – collect to the point that they prevent the release of heat from the atmosphere and prevent the planet from cooling. It killed Venus, and it might do the same to Earth if we don’t act in time.

Evidence suggests that volcanic activity began around 700 million years ago, restructuring the surface of the planet and transforming its atmosphere. The myriad eruptions over such a long period of time, and their damaging effects, produced the toxic mix of gases now found there. And the release of massive amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere kicked off the runaway greenhouse process and helped evaporate what was left of the planet’s store of oxygen. This process is apparently ongoing, as scientists have recently confirmed that at least some of the volcanoes are active.

Living on Hell? Colonizing Venus with “Cloud Cities” and Terraformed Oceans

Despite what you may imagine, there are people – serious-minded people, for the most part – who dream of somehow colonizing Venus. Some scientists have discussed the idea of establishing “floating cities” anchored atop Venus’s dense cloud cover, 30 miles above the planet’s surface.

NASA has discussed sending airships to Venus for a permanent settlement. The proposal even has a name: HAVOC, short for High Altitude Venus Operational Concept.

Although that might sound like pure science fiction fantasy, there are some reasons to think about it seriously. For example, at that level in the sky, the temperatures are actually pretty nice. Rather than the incinerating 800+ degrees Fahrenheit of the surface, above the clouds it’s calm and in the mid-70s, on average. Sounds nice, right? But here’s the downside: The clouds are composed of sulfuric acid and there’s no breathable atmosphere, so space scientists and other interested potential Venusian colonists would have a limit to the range of free movement for scientific tests or, especially, space tourism.

Artist’s conception of the colonization of Venus’s clouds by space stations and airships. (Source: MagellanTV)

Even more fanciful than these ideas, some space fabulists have proposed the concept of “terraforming” Venus by bombarding it with enough icy space rocks to return the planet to its pre-runaway greenhouse status, with deep reserves of water and cooling seas. One interested Internet user even came up with a visualization of what the planet would look like with deep oceans, continents, and islands.

Learning More About Venus's Past – and Future

Back here on planet Earth, perhaps we can better use our time and energy to appreciate the beauty of Venus, brightest planet in the sky, as it appears to us from more than 80 million miles away. Given its intractable hostility to supporting life – much less the fragility of humans traveling in a space vessel – Venus is, in all probability, uninhabitable. And it is visitable only at a respectful distance, and by unmanned craft.

One such explorer is the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter, whose mission to study the Sun is expansive enough to make at least five flybys of Venus along its way to the heart of our Solar System. The first flyby, slated for December 26, 2020, will add immeasurably to our knowledge of the cloud-shrouded planet.

The Solar Orbiter may not ever lead to human visits, but the knowledge we gain will help us understand better Venus’s origin story: what happened to Venus, and how it became the blazing infernal orb we see moving through the heavens.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title image: Surface of Venus (Source: Solar System Scope, via Wikimedia Creative Commons)