Why do some species spring back from extinction? The answers are surprising.

◊

Despite the strenuous efforts of great 19th-century scientists like Thomas Huxley, Herbert Spencer, and Charles Darwin, which forced the separation of evolutionary and biological sciences from the domain of the clergy, religious or biblical references continue to pop up from time to time in the scientific discourse. One such term is “Lazarus Taxa.”

The term was originally employed by paleontologist Adolf Seilacher in 1970. It refers to organisms that disappear from the fossil record for a significant period of time (sometimes millions of years) only to reappear later, like Lazarus in the New Testament, seemingly resurrected from extinction.

The term then transitioned into the realm of biologists and environmentalists. “Lazarus Taxa” has also been extensively used in the media, citing species that have suddenly been observed long after their supposed extinction.

Let’s take a look at the processes of extinction, and then focus on some specific species that appear to have, well, reappeared.

Human rescuers are working diligently to save critically endangered species. Check out MagellanTV's Saved from Extinction to learn about these vital efforts.

Why Do Species Become Extinct?

Scientists have identified a number of factors. First and foremost is the relentless march of evolution, through which species emerge and die out over eons of time due to predation or supersession by other species, availability of nutritional resources, or environmental changes to which they cannot readily adapt.

Evolution is generally a rather slow-moving process, but from time to time mass extinction events radically rejigger biology on our planet. There have been five such major events on Earth in the past half-billion years:

- Ordovician-Silurian Extinction – 440 million years ago

- Devonian Extinction – 365 million years ago

- Permian-Triassic Extinction – 252 million years ago

- Triassic-Jurassic Extinction – 210 million years ago

- Cretaceous-Tertiary Extinction – 65 million years ago

That fifth one, of course, involved the demise of the dinosaurs, which were essentially snuffed out when a huge asteroid smashed into Earth near what is now the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. But, as happens, the dinos’ rather sudden disappearance opened an evolutionary window for surviving species of snakes, crocodiles, turtles, amphibians, and mammals – the last group fortuitously (and over many millions of years) leading to us humans.

Fast forward to the Holocene epoch of the Quaternary period – that is, the past 11,500 years – and we can see that all this evolution and extinction of species over hundreds of millions of years has left us today with an estimated 5 million to 50 million species, only about one-thousandth of the estimated 5 billion to 50 billion species that have ever lived on Earth. And many of today’s species are disappearing at an alarming rate.

The Unnatural Acceleration of Species Extinctions

Scientists and environmentalists have identified a natural background extinction rate. Like the background radiation that suffuses the universe, it is hazardous and always present, but it is also rather minimal. A research paper published in Science uses a specific formula to understand background extinction events: 2 E/MSY (that is, two mammal extinctions per 10,000 species per 100 years.) This rate, which is a measure of the process of natural selection, is higher than previous estimates but also considered to be conservative.

Disturbingly, however, the actual extinction rates of various groups of animals is much higher than would be expected.

Applying the rate-of-extinction formula above to vertebrates generally, the number of species expected to have disappeared between the years 1900 and the present is nine. However, the actual figures collated so far by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (and used in the Science research paper), turns out to be not nine but 477. That’s 53 times more species extinctions than there should be.

To date, since 1900, we have lost 69 species of mammals, 80 birds, 24 reptiles, 146 amphibians, and 158 fish. This figure includes extinct species (EX), extinct in the wild (EW), and possibly extinct (PE). If there had been no human influence, those species should have taken up to 10,000 years to shuffle off this mortal coil.

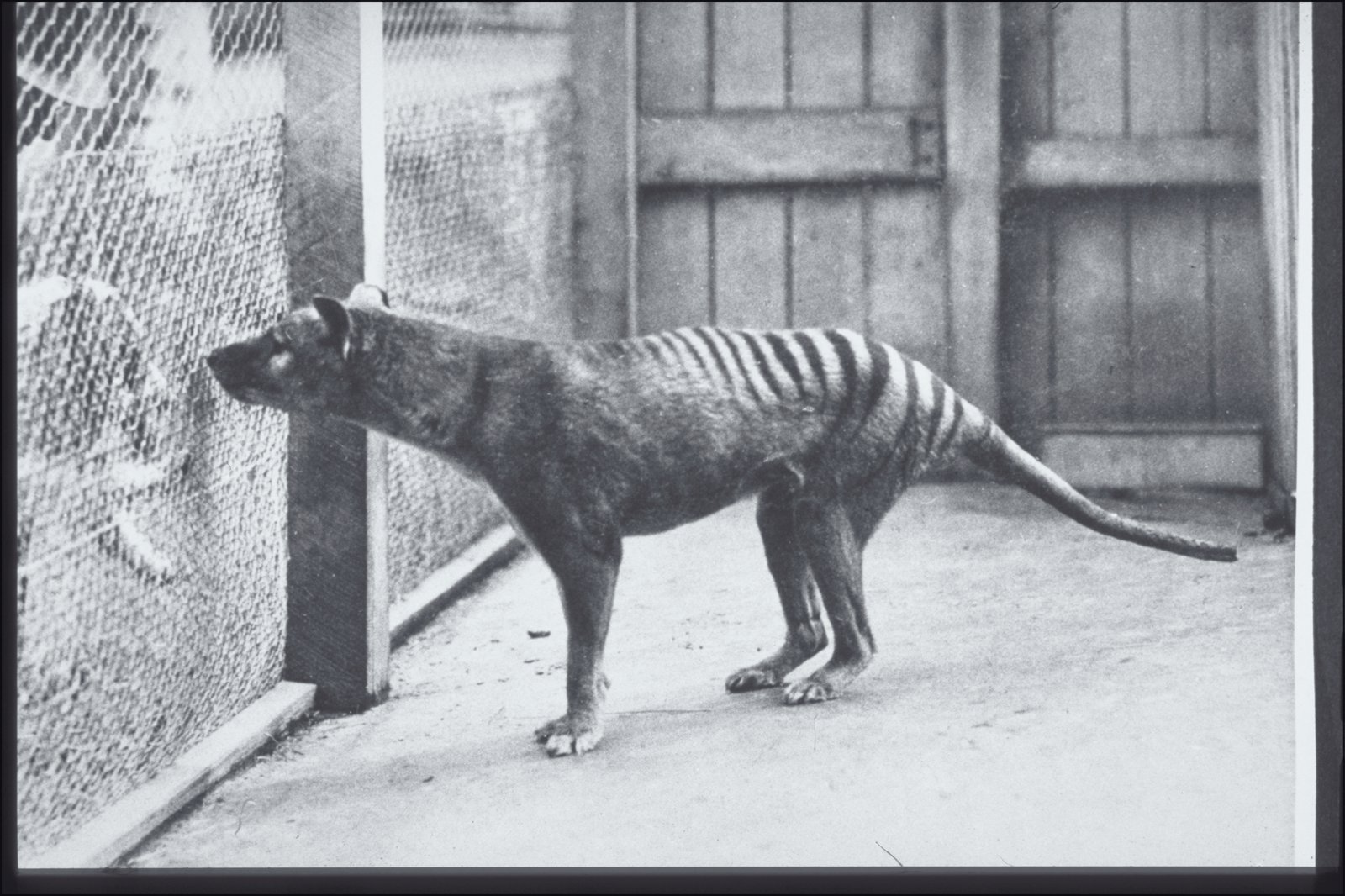

The sad fact is that, over time, we humans have hunted or eaten into oblivion multiple species. Notable examples include the dodo, Steller’s sea cow, the passenger pigeon, the Eurasian aurochs (cattle), the great auk (a species of penguin), the woolly mammoth, the moa (a giant flightless bird of New Zealand), several species of apex predator cats, and the Tasmanian tiger.

The last known Tasmanian tiger died in 1936. (Credit: Harry Burrell, via Wikimedia Commons)

Worse, there are the effects of climate change, which, of course, has been drastically accelerated by human activity. These effects have had far greater repercussions for species than previous climate events, due mainly to the speed of change. Many species simply do not have enough time to adapt to the rapid pace of anthropogenic climate change.

According to the IUCN, the changing climate results in ecological, behavioral, physiological, and genetic changes to species. Our warming planet also alters food chains, exacerbates the problem of invasive species, and affects the ability of plants to sequester carbon. The IUCN says that climate change affects 10,967 species on its Red List of Threatened Species.

Returning from the Brink: 5 Species that Have Reappeared

They shouldn’t still be here, but somehow a growing number of species once thought to be extinct are being rediscovered. Here are some notable examples:

The Coelacanth

Among the more publicized examples of Lazarus taxa is a fish with a face only its mother could have loved – the coelacanth. Relying on the fossil record, scientists believed this large, scary-looking creature had become extinct near the end of the Cretaceous period, 66 million years ago. But astoundingly, off the coast of South Africa in 1938, a live specimen of the coelacanth turned up in the net of fishermen.

Second rediscovered coelacanth specimen, brought to shore in 1952 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

A second specimen was netted near the Comoros Islands in 1952. Since then, numerous others have been netted, and researchers have learned that local islanders have been catching them for some time. Apparently, their flesh is quite tasty when dried and salted, and their rough scales are ideal for use as an abrasive.

Horseshoe Crab

Among the species thought to have gone extinct during this event is the horseshoe crab. But wait, you think, that species of crab is still with us. And you’re right. They thrive along the Atlantic coast of North America and in parts of Asia. So what’s up with that?

Horseshoe crabs at Cape May National Wildlife Refuge, New Jersey (Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, via Wikimedia Commons)

Horseshoe crabs can be traced in the fossil record back some 445 million years. Some scientists believe they may have gone extinct, and “reappeared,” several times since then. The theory is that this type of crab might live in an evolutionary niche that cannot be left empty. When one such arthropod becomes extinct, another evolves to fill the niche. It’s a process called iterative or convergent evolution in which – wait for it – “Elvis taxa” possessing similar features emerge to replace the extinct species.

Wollemi Pine Tree

Sometimes called “the dinosaur tree,” this conifer thrived during the Cretaceous period, according to fossil records. Scientists believed that it had been extinct for around two million years when a small grove of Wollemis was discovered in the Blue Mountains of Australia in 1994.

Wollemi pine displaying both male and female cones at Kew Gardens in London (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The tree is now classified as critically endangered, with only 46 mature trees and 43 younger specimens in the wild. (Some additional examples have been cultivated in botanical gardens.) In 2020, firefighters saved the indigenous Wollemis from a wildfire that threatened the grove.

Attenborough's Long-Beaked Echidna

Named after British naturalist and filmmaker David Attenborough, the fossil record of this elusive, egg-laying mammal dates back around 200 million years. It is native to the Cyclops Mountains on the Indonesian side of the island of New Guinea, and it had not been seen since 1961. Scientists thought that it was extinct.

Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna specimen from 1960 (Source: Naturalis Biodiversity Center, via Wikimedia Commons)

Then, in July 2023, an expedition from the University of Oxford got lucky when one of the creatures happened to walk in front of one of dozens of video cameras that had been set up in hope of finding proof that the creature still existed.

Mountain Pygmy Possum

Also known as the burramys (from an aboriginal word meaning “stony place”), this is one of five species of pygmy possums indigenous to Australia. It is known to hibernate for more than half the year, protected by boulders.

This rare mountain pygmy possum appears to be hanging on for dear life. (Credit: Zoos Victoria, via flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/australianalps/6954940609)

First identified in Pleistocene epoch fossils in 1895, it was presumed extinct until a living specimen was found in 1966 at a ski chalet in Victoria. Subsequent research discovered small colonies of the tiny marsupial in other alpine regions. But, as of 2017, there were fewer than 500 individuals extant in the wild.

Will Rescue and Rediscovery Raise Risk?

Understanding the mechanisms behind the reappearance of Lazarus Taxa can provide valuable information for conservation efforts, highlighting the importance of protecting vulnerable ecosystems that may harbor these hidden treasures. As human communities expand and encroach upon species’ habitats, and as the global climate shift alters and stresses those habitats, more creatures and plants once thought extinct may be rediscovered. Ironically, their reemergence may at first inspire wonder, but in the longer run expose them to greater dangers of an extinction from which there is no return.

Ω

Andrew Thomson is a science and technology television documentary producer from Melbourne, Australia.

Arthur M. Marx is Lead Editor at MagellanTV. He was previously a senior writer/editor at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. He lives in Sarasota, Florida.

Title Image: The Javan tiger was declared extinct in 2008, but more recent sightings and DNA analysis indicate that it is probably still extant. (Photo credit: Javan tiger skull, Klaus Rassinger and Gerhard Cammerer, Museum Wiesbaden, via Wikimedia Commons)