New technologies are later understood to have an enormous impact on human events. Two related inventions, the vacuum tube and the electric microphone, utterly transformed modern life, drawing people together in some ways, and in others forcing them apart.

◊

In reviewing the two decades between World War I and World War II, the subject of the fascinating MagellanTV series Impossible Peace: The Time Between World Wars, the pernicious effect of the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the first conflict, has been widely recognized as making the second one almost inevitable.

In the series, the recorded voices of notable individuals don’t appear until late in the second episode. This is, of course, because movies with sound weren’t developed until the late 1920s. And though it highlights other influential events of that time – the crippling illness of President Woodrow Wilson, the U.S. Congress’s refusal to join the League of Nations, the rise of Soviet strongman Josef Stalin, and the fateful ascents of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler – the series pays no attention to the era’s monumental technological advances (such as sound films), innovations which set the stage for events that seemed to spin the world out of control.

For more on the societal and technological developments of this turbulent era, check out Impossible Peace: The Time Between World Wars on MagellanTV.

We can now see that there were less-visible factors behind events in those turbulent decades. It wasn’t until our modern technological era was well underway that historians started to recognize the profound, often very disorienting, effects of new media. And it was not only technology’s role in remaking the social landscape – the railroads, automobiles, and electric grid – but the ways in which the rapid development of new products and processes transformed the inner lives of people around the globe.

The Future Arrives in a Vacuum Tube

It is not an exaggeration to say that new human inventions have the unexpected outcome of inventing new humans. The ideas, ambitions, and interests of people, the conditions making up their inner lives, were given broad new avenues of action – for both good and ill – by the emerging technologies.

And while it is of central importance to understand the 20th century rise of America as a world power, along with the parallel ascent of European fascism and Soviet authoritarianism, as the outcome of powerful people and institutions, these events could not have unfolded as they did without the enormous advances in the technologies of the era.

I am thinking specifically of two intimately related inventions – the first one readers under 30 may never have heard of, the second now so common as to have become invisible in our modern world.

The first is the electric vacuum tube, grandparent of the semiconductor; the second is the electric microphone. Together they utterly transformed the world between the two great wars, not just on the stages of public events but the realm of our private lives as well.

I’m prepared to make the case that no single invention has changed more media in more profound and lasting ways, and with a greater effect on history, than the electric mic. First, though, we need to get to know that amazing tech dinosaur, the vacuum tube.

Radio Waves and the Drive for More Power

When Guglielmo Marconi established the principle and practice of the remote transmission of radio waves in 1895, competing researchers were in a race to find ways to amplify broadcast signals. Even as improvements were made in boosting signal power, for two decades wireless communication was conducted via the dots and dashes of Morse code. Put simply, early radio didn’t yet have the bandwidth to transmit voice communication.

Long-distance voice transmission had existed for decades via telephone, which used a network of copper wires powered by close relays of DC-current substations. Voices were picked up by relatively cheap and simple microphones that were basically thin metal boxes filled with carbon powder that converted the vibrations of speech into an electric signal. This was then relayed to an earpiece diaphragm that translated the current back to recognizable sounds.

The word microphone, or “tiny sound,” was coined in 1827 by Sir Charles Wheatstone, inventor of the telegraph, who also studied ways to send sound over long distances.

But even state-of-the-art telephone communication was thin, scratchy, prone to line noise, and reliant on much more electric current than that available to radio technology.

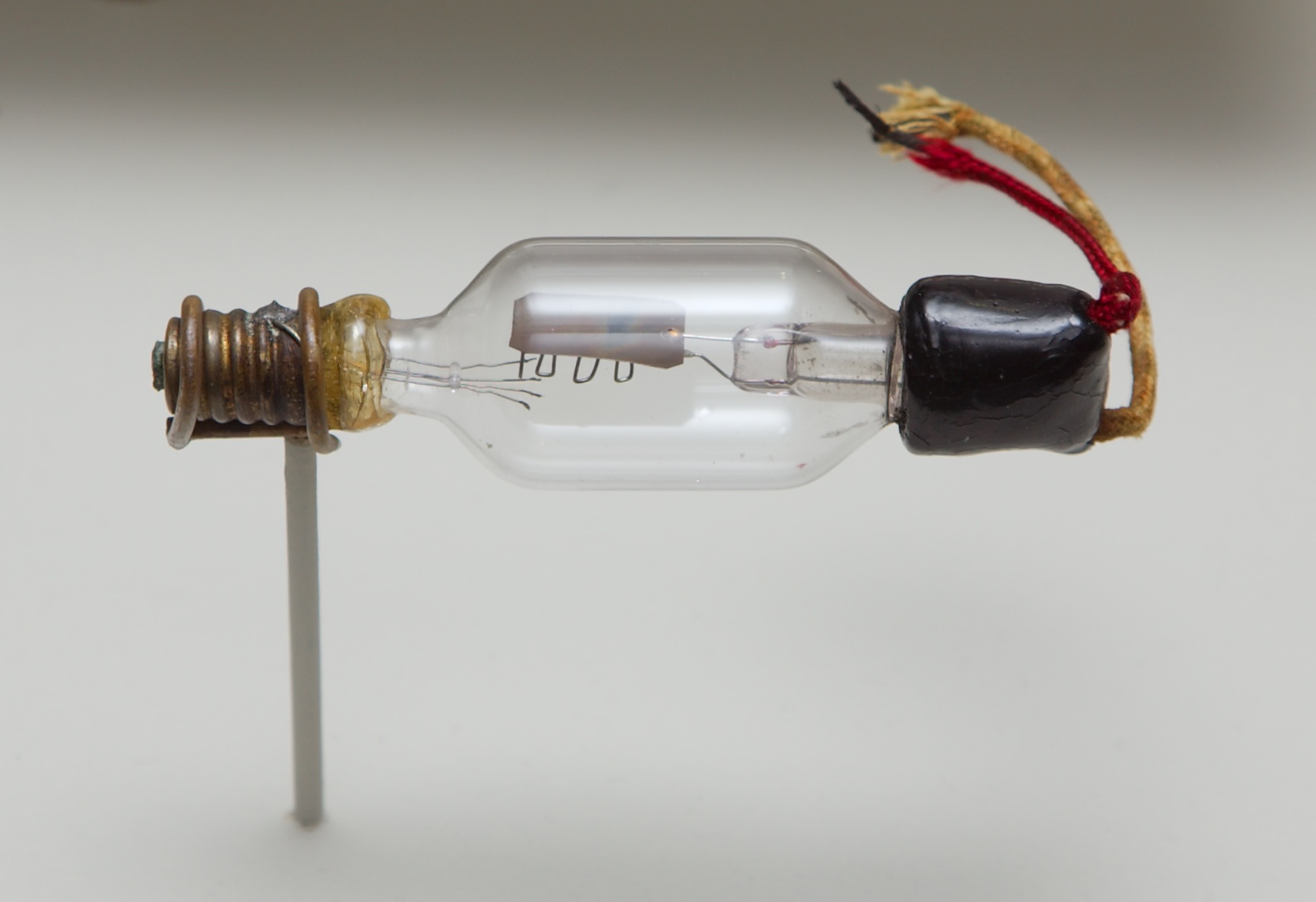

But in 1906, an independent American inventor, Lee de Forest, utilized technology based on the high-current capability of light bulbs. He realized that a thin filament in a vacuum glass tube was sensitive enough to pick up radio waves. His first invention – which he called a diode tube – was powered by an electrically charged plate. Moderately effective, it suffered from too much signal loss.

Lee de Forest’s first triode tube. (Credit: History of San Jose, Perham Collection of Early Electronics via Wikimedia)

De Forest’s further innovation was to add a shielding filament that focused and further amplified the signal. This triode tube not only boosted the radio signal, but de Forest realized that, since electric current could travel in only one direction, a connected relay of three of these tubes greatly amplified the transmission, and reception, of radio signals.

Though obviously successful in the lab setting, de Forest’s triode system needed further improvements for reliability and efficiency. Given a contract to supply the Navy with tube radio receivers during World War I, the de Forest system worked, but not especially well.

Though they were competitors, de Forest and the Marconi company, which had been conducting its own innovations to the technology, reached an agreement to manufacture and market the improved vacuum tubes. Once the Great War ended, development resumed and the units were soon directed into myriad consumer market applications.

Vacuum Tubes Bring on AM Radio

An immediate innovation was the birth of AM (amplitude modulation) radio (it should not surprise us that de Forest started one of the first stations in 1920). The first radios tuned into these stations using filaments encased in crystals and required headphones to hear the signal. These were soon enough replaced by bulky receivers resembling pieces of furniture that encased a tube relay in a heavy, electrically charged base that sent signals to a speaker.

A 1922 crystal radio set from Sweden. (Credit: Ellgaard Holger via Wikicommons)

The advent of broadcast radio then created a need for higher-fidelity audio that the vacuum tube was also able to produce. The solution – an electric microphone – would help form our modern world.

In 1916, an engineer at the Western Electric company had developed the condenser microphone. It had basically a two-plate system resembling the telephone unit, but now without the carbon powder interface. Relying on the high-power input provided by vacuum tubes, the condenser’s two diaphragms connected to a magnetic coil to produce a charged signal.

The classic Shure 55s condenser microphone; introduced in 1955 and, with many improvements, still made today. (Source: Wikicommons)

Less than a decade later, the new ribbon microphone appeared, which replaced the condenser’s diaphragm/coil design with one using a thin strip of metal set between two magnets. Both types are still in use. Condensers are heavy, durable, and are what you see musicians using for live performances. Ribbon mics are more fragile and produce a wider tonal range, and so are mainly found in radio and recording studios.

By 1924, AM stations were up and running from coast to coast. A major outcome of this increased aural bandwith was the addition of live music programs. Local entertainers, many in rural areas, now had wide audiences for short daily musical interludes, usually advertising nearby businesses.

By the 1930s, AM radio stations in Mexico, designed to broadcast across the United States, were so powerful that their signals could be picked up by and faintly heard over barbed wire fences a few miles away in Texas.

These early broadcasts not only gave birth to our modern world of commercials, it would soon enough revolutionize the music business.

Electricity Makes the Record Business an Industry

Since its commercial debut in 1890, the phonograph had been a rich person’s status symbol. Recordings were fully analog. To make records, performers played and sang as loudly as they could into the wide mouth of a huge funnel at the other end of which was an oscillating needle that engraved sonic vibrations onto a spinning wax matrix. This was then copied for manufacture.

An orchestra at the Victor record company playing into an acoustic horn, ca. 1921 (Credit: Science Museum Group Journal)

For 30 years, commercial records catered to the tastes of the affluent – sentimental ballads, marching band music, and classical pieces prevailed. But once radio stations began live music programming, record sales crashed.

The great opera tenor Enrico Caruso never sang into an electric microphone. At his 1921 death, Caruso’s many recordings accounted for an astounding 24 percent of all records sold.

In reaction, company executives wisely decided to make records of music people actually wanted to hear and so set up regional sessions to find and promote local talent. Until the Great Depression temporarily shut down the record business a decade later, an amazing array of musicians produced truly democratic and popular American music – blues, country, and jazz – with players Black and White contributing to each genre.

Electric amplification also brought a sea change to music performance. Singers were freed from having to shout to be heard over a band. Now, softer, more dynamic and intimate vocals were possible during live shows. Crooning became the new singing style. Bing Crosby, Billie Holiday, and Frank Sinatra are three of the most recognized performers who created new realms of vocal expression in popular music.

Performance and Politics in Amplified Sound

Of course, the most visible application of the new sound technology was at the movies. All that pop music had to go somewhere, and the silver screen was one obvious destination.

And though sound added great new expression to films – fantastic musical numbers and snappy dialogue are hallmarks of American movies in the 1930s – it also had the unfortunate effect of ending the production of silent films. A truly international artform, the easy exchange of movies across the barriers of language ended with the advent of sound. By the 1930s, an international movie market that had evolved since 1900 fragmented into several national ones. While this was probably inevitable, as the ’30s progressed, and fascist regimes grew in Europe, nationality-based sound films became very effective propaganda vehicles.

Possibly the most dire effect brought by the electric mic was to give the power to a single person to address a mass audience, either during a political rally or on the radio, which was now able to broadcast political rallies.

President Franklin Roosevelt prepares to deliver his first radio “Fireside Chat,” March 12, 1933. (Credit: Library of Congress)

In America, President Franklin Roosevelt famously used radio for “fireside chats” meant to reassure the nation during the worst of the Great Depression. At the same time, American fascists and anti-Semites, like the “Radio Priest,” Father Charles Coughlin, spewed hate across the same medium.

Fatefully, in Germany huge rallies were orchestrated to bring the voice of Adolf Hitler to tens of thousands in attendance. When one at Nuremberg was filmed in 1934 for the Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will, the worst aspects of the century’s latest media became all too real.

Adolf Hitler addresses the German nation via radio on being made chancellor in January 1933. (Credit: German Federal Archive via Wikimedia Commons)

Later, after the second world war ended, vacuum tubes powered three generations of TV sets as well as the first IBM computers. By the start of the 1970s, solid state transistors had replaced vacuum tubes in radios and TV sets. Today they are mainly found in high-end audio equipment and guitar amplifiers, valued in both for the warmth and roundness of their tone signal.

Of course, it only took about 20 years for transistors to give way to semiconductors, launching the disorienting technological wave engulfing us now, one that’s possibly as deep, but not nearly as wide as the one launched by de Forest’s vacuum tube.

Ω

Contributing writer Joe Gioia is the author of The Guitar and the New World, a social history of American roots music. He lives in Livingston, Montana.

Title image: An array of vacuum tubes (Credit: Stefan Riepl via Wikicommons)