[Editor’s note: This article, by acclaimed documentary filmmaker and MagellanTV co-founder Tom Lucas, was originally published in October 2018. We’re bringing it back as part of our series commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission to the Moon.]

A humble collection of rocks and dust brought back by Apollo astronauts revolutionized our understanding of Earth’s history and our own origins – and may have revealed a catastrophic collision between Earth and a previously unknown early planet.

◊

When Neil Armstrong became the First Man to step on the Moon on July 20, 1969, he famously invoked a giant leap for mankind. His words echoed those of President John F. Kennedy, who set the Apollo program in motion in 1963 by appealing to the boundless hopes of a post-war generation.

However, it has taken time for Apollo’s legacy to settle in. At the time, the American public was decidedly ambivalent. With the exception of a brief period following Apollo 11, less than half the public actually supported the program. That widespread skepticism, in a time of war and social unrest, may have ultimately led to its cancellation.

Even scientists had their doubts. In a poll by Science magazine, an overwhelming majority of non-NASA scientists expressed concern that manned exploration of the Moon was premature.

However, in the decades since, a solid majority of Americans has come to support the missions. Scientists have come around as well. And in recent years, the scientific rationale of the Apollo Program has begun paying off.

Moon Formation Theories through Time

As a major, but largely unheralded, part of their mission, astronauts were sent to gather clues to the origin of the Moon. Finding out would provide insight into the formation of the solar system at large, and even to the birth of our own planet. There were three leading theories:

1. The Fission Theory

The so-called fission theory was championed by George Howard Darwin, son of Charles Darwin, and by others even up to the time of the Apollo missions. It held that the Moon was once part of the Earth, cast off by the rapid spin of its young parent.

The proponents of this theory saw the Pacific Ocean as a giant scar on the Earth’s surface that was linked to the Moon’s formation. Today, scientists know that the crust beneath the Pacific is relatively young, some 200 million years old, while the Moon is much older.

2. The Capture Theory

The capture theory was popular until just a few decades ago. It held that the Moon was a wayward object floating through the Milky Way galaxy. At some point, it wandered into the young Solar System and was pulled into orbit by Earth’s gravity.

Astronomers have spotted many examples of objects that were similarly captured by planets, but few of them are as large as our moon. The main difficulty with this theory is that most captures result in highly elliptical orbits or even collisions. Earth would have needed a very large atmosphere with enough friction to pull the Moon into its current orbit.

3. The Condensation Theory

A third idea came from the American astronomer Thomas Jefferson Jackson See, known for his attacks on Einstein’s theories. He suggested that the Moon is actually a small planet that coalesced from the same material that formed the Earth.

The Moon then gradually fell under Earth’s gravitational spell, forming a double planet system. This explanation – also known as the co-accretion theory – suggests that Moon rocks should resemble those of Earth, but does not account for the very different sizes in the iron core of the two bodies.

What Happened in 1969

Neil Armstrong and the 11 moon-walking astronauts that followed stepped onto a strange world of optical illusions and odd juxtapositions. The lunar landscape appeared monochromatic, a bright gray. With no atmosphere, the light was harsh, and shadows were cast in deep black.

But close up, the Moon offers a variety of rich and colorful details owing to its tumultuous past. Its rocks and minerals reveal a record of violent impacts, vast outpourings of lava, and variations in solar radiation.

The astronauts explored the lunar surface to observe, take readings, and collect rocks. Armstrong and his partner, Buzz Aldrin, packed a container with 47.7 pounds of lunar material from a region called the Sea of Tranquility.

In total, the six Apollo missions brought back 842 pounds of rocks, dust, sand, and pebbles… 2200 samples from six widely varied sites.

Birth of the Giant Impact Theory

One of the rocks picked up by the Apollo 12 astronauts is known as KREEP, for potassium (K), rare earth elements (REE), and phosphorus (P). It’s thought to be a piece of bedrock that formed over 4 billion years ago on a surface that was entirely molten. This and other evidence lent support to a radical new idea introduced by scientists in the 1970s. The giant impact theory has since become the accepted understanding of the Moon’s origins.

The giant impact theory holds that, at the dawn of the Solar System, Earth shared an orbit with a Mars-sized body researchers now call “Theia.” According to the theory, when Theia’s orbit became unstable, it headed in Earth’s direction and struck at an oblique angle. This caused Earth to spin faster and debris from both bodies to fly into orbit.

When the dust from the “giant impact” settled, the debris coalesced in Earth’s orbit, forming the Moon. From this violent beginning, the Moon gradually cooled, and the magma that wrapped its surface hardened into a crust.

For the giant impact theory to hold up, it would have to explain crucial attributes of both the Moon and Earth, including their relative sizes, spin rates, and distance from each other. Explaining these attributes, it turns out, is central to one of the most important questions in all of science: How did Earth’s climate evolve, billions of years ago, and become stable enough to nurture life?

Origin of the Moon

Scientists believe that in the time before the Moon, the inner solar system would have had around 20 small planets that combined to form the four we know today, plus Theia. Like Earth, Theia would have had an iron core and a silicate mantle, with a size comparable to Mars.

If that body hit Earth at an off-center angle, it would have been enough to set Earth spinning at a rate of about once every five hours. As it turns out, that’s the speed needed for the Moon’s gravitational pull to settle Earth gradually into its current 24-hour day.

RECOMMENDED: Want to learn more about the birth of the solar system?

Watch How The Earth Was Made. This award-winning series goes back in time to peel back layers of rock, diving into river canyons, parting the oceans, and leveling mountains and volcanoes to investigate the origins of some of the most well-known locations and geological phenomena in the world.

Read How the spacecraft Juno has revealed the secrets of Jupiter. This mightly gas giant played a key role in the formation of Earth, and some argue the gravitational protection it offered was key to the formation of Life on Earth.

It was only in the last decade that scientists could begin to test these ideas. With the advent of supercomputer models, they were able to recreate the event virtually, in all its violent glory. Using these models, they set about testing a wide variety of parameters to pinpoint the masses of the planets, their composition, and the angle and speed of the impact.

The leader of this decades-long effort, Dr. Robin Canup of the Southwest Research Institute, describes the sheer spectacle of the impact: “From the perspective of someone on the Earth at the time, what you would've seen is an enormous object approaching the Earth, many, many times larger than the full Moon in the sky.”

The impact would have sheared about a third of Earth away. Dr. Canup’s simulation shows that on a timescale of just a few hours, a shockwave would have engulfed the planet, creating a thick atmosphere of vaporized rock heated to over 5,000 degrees.

With Earth now spinning rapidly, much of the debris set loose by the impact formed a disk around it. Some of the debris fell back, subjecting Earth to a rain of secondary impacts. The rest stayed in orbit. According to Dr. Canup, “We think that on a much longer timescale, of about 100 years, that disk will cool, the vapor will condense, and out of that disk, through collisions within it, the Moon would have formed.”

What We Know Today

The exact details of the impact are still being debated and tested through simulations and ongoing analysis of the Apollo rocks. The event that formed the Moon has been folded into broader theories about the evolution of the Solar System as a whole, and compared to revelations about star systems being discovered across the Milky Way galaxy.

NASA and other space agencies have continued to fill in details of lunar history through a succession of robotic missions. Scientists have taken the analysis of extraterrestrial bodies to whole new levels with sample-return missions to comets and asteroids, and mobile labs that roam the surface of Mars.

To push science forward rapidly, the Apollo missions showed that there is still nothing better than human hands, and discerning human minds, to see, explore, and learn.

Ω

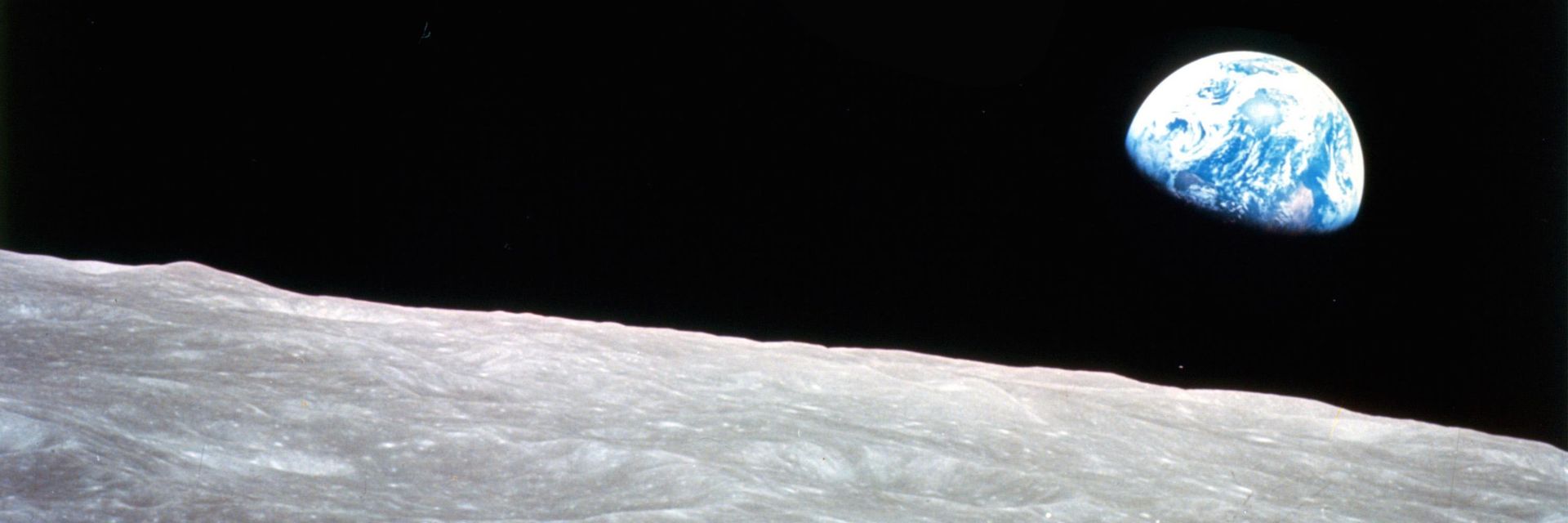

Title image: A view of the Earthrise from the Moon by NASA (Source: Wikimedia Commons)