Owls have fascinated people for thousands of years. Their rapt stare and haunting night calls have made this mysterious bird appear to people worldwide as both keepers of great wisdom, and agents of dark, supernatural forces.

◊

I attended a small college in central Ohio – an assortment of Gothic stone buildings dotting a leafy rural hilltop. Early one evening my senior year, I made my way to a lookout point with a view of a small river’s valley, a panorama of dairy pastures interlaced with stands of trees.

Having the view all to myself, I settled into an absorbed contemplation of the nearly timeless view before me when there came from behind the weirdest sound I’d ever heard before – or since. It was a kind of short, hideous barking, definitely demonic, and very loud.

Startled, to say the least, I spun around and soon saw the source of the weird cry. In the top branches of an ash tree, about 40 feet above me, was a dark and hulking creature. It was an enormous great horned owl, clearly scanning that picturesque river valley for dinner.

I’ve been kind of gaga about owls ever since.

Because they are mainly creatures of the night, owls inhabit vast tracts of the human imagination. While other birds have abiding places in the realms of symbolism and myth (Odin’s raven, Noah’s dove, and the baby-bringing stork, to name but three), no bird has come to signify more things to more people than the owl.

So, in honor of that awesome bird that allowed me a glimpse of the truly wild, let’s take flight into the realms of myth and storytelling with humanity’s most attentive avian companion.

Learn about the needs and skills of snowy owls in the beautiful MagellanTV documentary A Winter’s Tale.

What’s in a Name? Hoo Knows!

Right from the start, the most distinctive feature of owls, unique among avian species, are two forward-facing eyes set in a round, relatively flat face. While the look isn’t exactly human, neither is it classically birdlike.

In the animal kingdom, binocular vision is a feature common to all land-based predators: cats, canines, and everyone in the ape family, while prey species get by with two, mostly independent orbs, one on each side of their faces, and scan as much ground as possible for any forward-facing menace.

It was perhaps in recognition of this quasi-human feature that Indo-European cultures named the owl in terms of how it spoke to them.

In English, for example, owl is descended from the Old Norse ugla, and earlier Old Teutonic words that are, as noted by the Oxford English Dictionary, “derived from the voice of the bird.” The Old English name ule dates from 725 CE and is also connected to (my favorite) the Latin noctus ulula, which we can translate as “night howl” (and yes, “howl” and “owl” are very much related).

But why stop there? In German, the bird is called eule; Franch, hibou (pronounced hee-boo); Spanish, buho (boo-ho); Italian, (another fave) gufo (goo-fo); and in Hindi ulloo. Simply put, we’ve been listening to owls for as long as we’ve been humans. It is logical then that people have wondered what exactly it is that they have to say to us.

The Archetype of Owls in Western Culture

Perhaps the penetrating nature of their wide eyes, or how they can sit so calmly, just watching things, gave owls the mythic characteristic of wisdom in the West. Their remarkable ability to rotate their heads 270° (thereby encompassing almost all aspects of a situation) would have also added to the legend.

An owl on a silver drachma coin from Athens, minted ca. 135 BCE. (Credit: ArchaiOptics/Wikicommons)

In recognition of this apparent sagacity, the Athenian Greeks made a small owl the favorite of Athena, their Goddess of Wisdom. Representations of her commonly show the familiar animal perched on her shoulder. In recognition of its presumed qualities of great knowledge and vigilance, the Athenians put the owl on its coins, a guarantor of honest and prudent trade. (That the bird Americans chose to place on their currency, the Bald Eagle, has a similar symbolic appeal for commerce – vigilance, honesty, and courage – is rarely commented on.)

Adding to its appeal for the Athenians was the colony of small owls that roosted in the nooks of the Acropolis, the highest point in that city then and now, where they likely did yeoman’s work clearing the surrounding area of rodent pests.

“A dead owl nailed to an ancient Roman doorway was meant to ward off evil.”

Outside Greece, their haunting night cries, and, thanks to the design of their unique feathers, their silent flight made owls more sinister agents. Though the Roman god of sleep, Hypnos, commonly took the form of an owl, Romans generally considered them more ominous and less sacred than the Greeks. A dead owl nailed to an ancient Roman doorway was meant to ward off evil. It’s notable that the Romans, who otherwise mimicked Greek culture whenever possible, gave owls more malign qualities, raising the eagle as their imperial totem animal instead.

Owls were said to have prophesied the killing of Julius Caesar, a tale illuminated by William Shakespeare in his classic eponymous tragedy, writing: “Yesterday, the bird of night did sit even at noonday upon the marketplace, hooting and shrieking.” (Act I, scene iii)

That owls do not build nests, but instead roost in hidden nooks of trees and buildings, also likely set them apart from other birds in the estimation of our ancestors.

"Owls seen living in sacred oak trees were thought to have mystical powers beyond mere wisdom."

In northern Europe, owls seen living in sacred oak trees were thought to have mystical powers beyond mere wisdom. For the Norsemen, these hunters who could see in the dark were considered spirit guides, leading souls after death to their destinations in the afterworld.

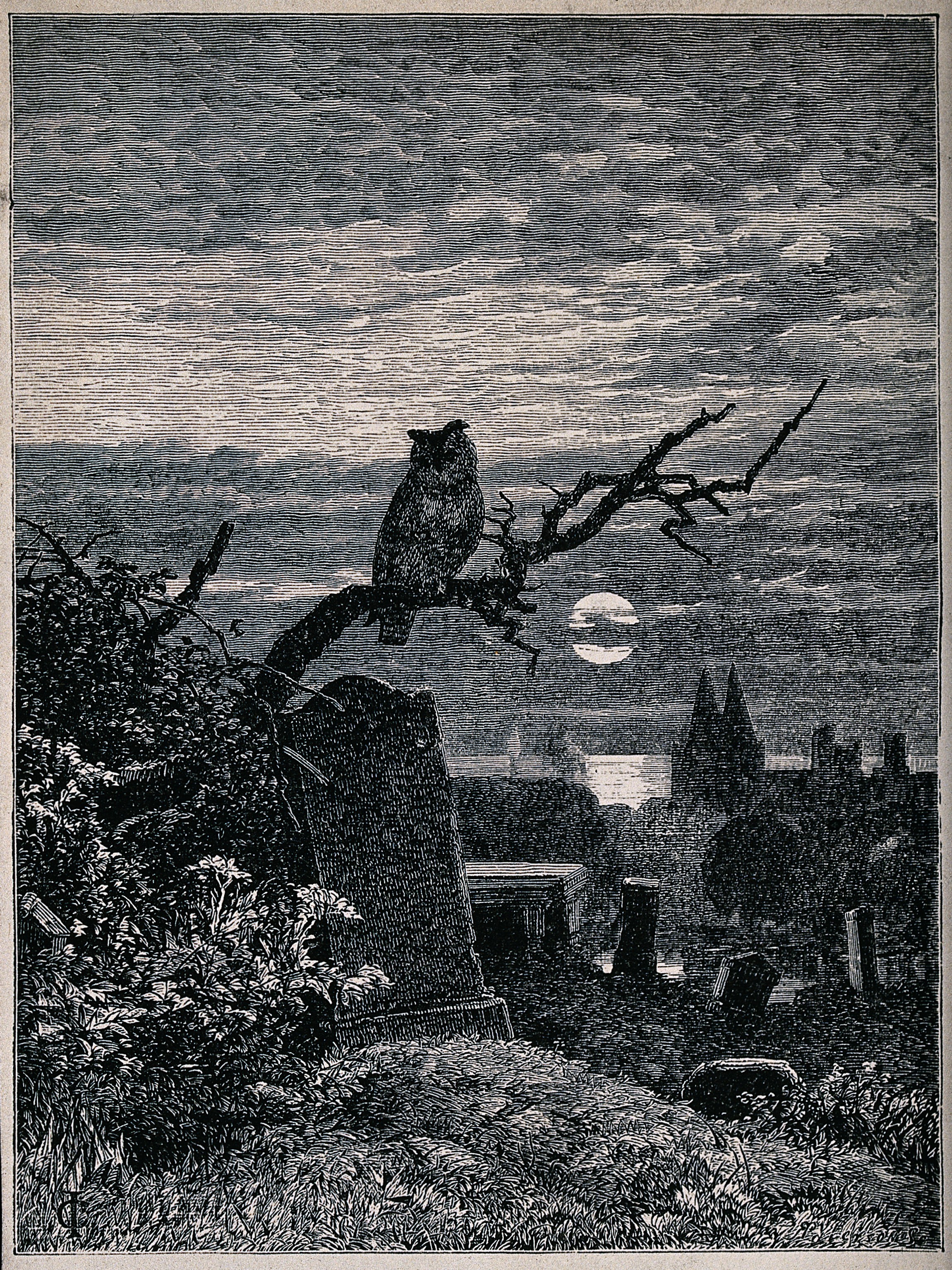

A 19th century engraving by Robert Paterson of a lonely English graveyard, which would not be complete without an owl. (Credit: Wikicommons/Wellcome Library)

It should come as no surprise then that as Catholicism gradually encompassed Europe, the more sinister Roman characteristics of owls held sway. As pagan customs and holidays gave way to the Christian calendar, owls became the companions of witches. Instead of guiding souls to the afterlife, the birds were considered to be sure signs of ghosts and earthly decay.

It is altogether notable that the reservoirs of ancient respect given owls allowed them to hold on to their status as agents of wisdom and guidance even as they were demonized. Today you will see cardboard cartoon owls decorating walls at Halloween parties and school graduation celebrations alike. For some reason, no one finds this particularly odd.

A Guide and Protector to Native Americans

It should come as no surprise that owls figure prominently in the lore of the native people of North America. Interestingly, these cultures, so far removed from the streams of Indo-European migration, also broadly consider owls messengers of impending death as well as guides for the souls of the departed to the next world. The Ojibwa people, for example, call the span connecting this world to the next one the Owl Bridge.

For native people, owl feathers and other remains have totemic powers to stave off sleep and help watch for enemies at night. In one variety of indigenous creation myths, day was divided from night by a contest between Rabbit and Owl. Rabbit, wanting more light to see things by, won their game but allowed Owl to keep some darkness for himself.

As might be expected, the small burrowing owl, a species that takes up residence in vacant rodent dens, and whose territory stretches from Alberta, Canada to Argentine Patagonia, is sacred to the Hopi people not only as an ambassador from the underworld but one in charge of, among other things, the germination of plants in the spring. The Hidatsas of the northern American plains considered the great horned owl as a kind of spirit game warden, guiding and protecting buffalo herds with help from his assistant, the burrowing owl.

A snowy owl photographed in Michigan. (Credit: Bill Bouton/Wikimedia Commons)

Modern Mythological Owls

As nearly all my readers are surely aware, any survey of mystic owls needs to include those assigned to every student at Hogwarts in the Harry Potter stories.

As seen in the films drawn from that series, the owls, which act as supernatural messengers, range from Harry’s snowy owl Hedwig to burrowing, screech, gray, and eagle owls. Certainly the films invoke the mystery and awe surrounding the birds very adroitly, and probably explain the crowds that gathered around a snowy owl that found its way to Los Angeles in early 2023.

My own academic owl, high in that tree overlooking the river in Ohio, was the last one I would see for a long time. Occasionally, when living in New York, I’d spot a distinctive silhouette perched on the ledge of a high building only to be disappointed to realize it was, in fact, an inflatable replica meant to discourage any local bevy of rock doves – that is, pigeons – from congregating nearby.

After decades of big city life, I came to live in a small town in Montana, and am pleased to report that every so often, late on cold nights, I will hear the hooting of what I presume is another great horned owl. At least that’s the bird I saw at the top of the microwave tower across the street from my home as dusk was turning into night a few years ago.

As for the birds back at my alma mater, I was astonished to learn long after graduating that the name of the river I was so used to admiring, Kokosing, is drawn from the Delaware Indian word meaning “a place of owls.”

When the time came in 2022 to change the very-gendered names of the college’s men’s and women’s sports teams, the choice of a new one was put to a vote. Students and alumni were given several possibilities. I’m pleased to report the hands-down winner: From here on out I will cheer happily, win or lose, for the Kenyon Owls.

Ω

Contributing writer Joe Gioia is the author of The Guitar and the New World, a social history of American roots music. He lives in Livingston, Montana.

Title image by Sabrina D’Agostino