Chickens may be humans’ favorite (edible) domesticated animal. Nowadays, at least in the United States, chicken is the most popular source of protein, besting both beef and pork. And there are literally billions of chickens all around the world. Let’s dig into chickens for a delightful – and delectable – ride through the history of time with these flightless winged creatures.

◊

How best to tell the story of the ubiquitous, underappreciated chicken? Well, to answer this question, we have to journey back some 66 million years to a time when dinosaurs ruled the world.

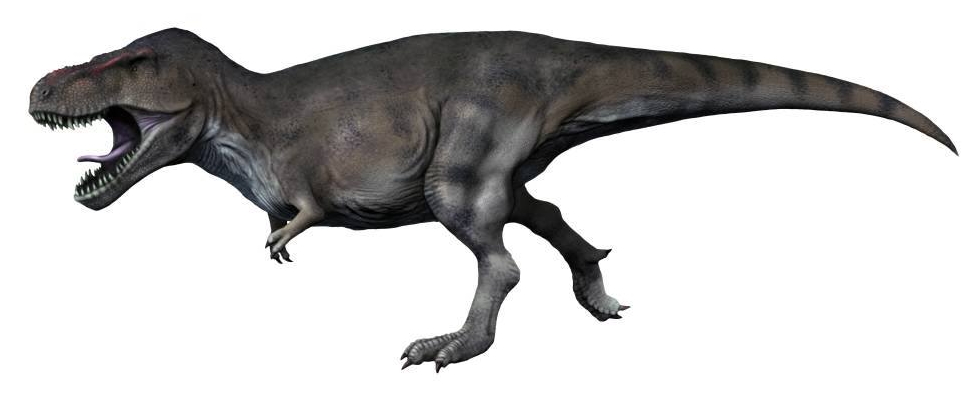

The fearsome mega-predator Tyrannosaurus rex, or T. rex, roamed the wild open spaces of western North America back in the Cretaceous period. T. rexes were massive creatures, and could reach as much as 20 feet tall and 40 feet in length, towering over their rivals such as Triceratops and smaller creatures. The species thrived for more than two million years, according to archaeological evidence, dominating its environment until the violent end of the period.

Then, scientists theorize, a large asteroid collided with the Earth, putting the kibosh on the era as well as on the lives and long histories of the big dinos (and most other species) in one fell swoop that shook the entire planet.

Notice the resemblance? T. rex's most direct descendant on the Earth today is the chicken. (Source: Nobu Tamura, via Wikimedia Creative Commons)

But did the histories of the monstrously large species come to a cold, hard terminus with the rapid collapse of the Cretaceous? Recent research tosses cold water on the belief that T. rex reached the end of its family line on that fateful day. Somehow, despite the massive worldwide wreckage, die-outs, and destruction, at least a couple of T. rexes lived on to mate again.

Know your chicken! An adult male is a rooster, and the female is a hen. Younger, they are called pullets for females and cockerels, or cocks, for males. The plump, tasty chicken we’re likely to enjoy for dinner is a capon, a castrated male chicken.

What happened to their descendants? DNA tests and other evolutionary biology investigations reveal that a direct descendant of the formidable theropod is alive and kicking today. Over the eons, Tyrannosaurus’s heirs got smaller and took wing, so to speak. (Current research suggests they may have already had feathers.) After more than 60 million years and at least one extinction event, the closest relation on our planet today to the mighty Tyrannosaurus just happens to be our ubiquitous domesticated chicken. Squawk!

Watch Chicken Planet on MagellanTV.

The Domesticated Chicken: Descended from Giants

Where does this unjustly under-celebrated bird come from? Examining its current global footprint – or claw print, if you prefer – won’t help much in discovering its origin. That’s because, today, chickens are found virtually everywhere around the planet that humans dwell, from far northern climes through equatorial environments and down to Cape Horn, the southern tip of South America.

Genetic discoveries point back to one broad geographic area where chickens seem to have emerged from the intermingling of two wild species, red and grey junglefowl. That region is Southeast Asia, where organized breeding of fowl likely began as far back as 10,000 years ago. Rivaling this history is the evidence for chickens coming into their own in the Indus Valley of India approximately 6500 B.C.E. Despite research indicating early domestication over time in both locations, chickens’ genetic makeup across the world is remarkable for its lack of variation. There are scores of domestic breeds, but their genetic diversity is relatively narrow.

Are there chickens in Antarctica? Well, some places are clearly not supportive of a chicken’s natural well-being, and, though individuals have dined on chicken there, flocks of chickens have never been raised domestically on the southernmost continent. There is, in fact, a ban on the importation of chickens to Antarctica to protect the safety and health of its natural avian potentate, the emperor penguin.

In the United States, there are about 20 billion chickens at any given time. Eight billion are consumed annually for protein, and 300 million layers are active, producing more than 250 million eggs daily.

Chickens, then, seem to come from everywhere and nowhere. We know that, in nature, chickens have a very small range. They are poor aerialists; it’s rare to see them anywhere above ground for any amount of time. So, most places that have hosted domesticated chickens (and that is literally “most places”), have had their chicken population spurred to life by human migration. Where we go, and where we’ve gone, we’ve pulled pullets along with us. We’re even discussing taking chickens into space as we hatch our own plans for life beyond this planet. Imagine, “One small step for a capon, one giant leap for all poultry!”

Evolution of Chickens: From Fighting Cocks to Divine Messengers

If the mere mention of “chicken” makes you want to sink your teeth into a golden-brown, sizzling drumstick right out of the skillet, you’d be disappointed to travel back to 6,500 to 8,000 B.C.E. for a tasty meal. In fact, studies have shown that millennia passed before chickens were raised for food. Despite their delicious eggs and meat, these key elements of chickens’ appeal were unknown until the time of the Greek and Roman empires.

.jpg)

Two fighting cocks depicted in this rescued mosaic discovered at Pompeii. (Source: Naples National Archaeological Museum, Carole Raddato, via Wikimedia Creative Commons)

Before then, about 3,000 years ago, chickens were certainly prized, though not for what you’d think. Instead, for thousands of years roosters were bred for their fierceness as fighters. It was sport, not nutrition, that originally made chickens appeal to the people who raised them. The origins of the blood sport of cockfighting for the amusement of humans are somewhat indistinct, though evidence abounds of its existence and popularity over many centuries.

Historical evidence of the so-called “world’s oldest sport” is found across many lands, from China to India and beyond. A tile mosaic found in Pompeii marked the location of a cockfighting “salon,” and, in the Greek town of Pergamum, an archaeological dig uncovered a cockfighting amphitheater most likely built to inspire young soldiers with the valor and bravery displayed by roosters bred to fight to the death.

The chicken’s genetic ancestors, red and grey junglefowl, share a strong need to dominate their flock and are built for brutality. In particular, they have sharp beaks for jabbing and razorlike bone spurs for kicking and slashing. They are aggressive and highly social, seemingly unafraid to be tested for dominance of the flock, and willing to fight through pain and injury to succeed.

Most countries, including the U.S., have outlawed cockfighting. The putative “sport” was last permitted legally in the U.S. in 2007, in Louisiana. In ancient times, however, fighting cocks were important to the structure of society and its peoples’ needs for socialization and entertainment.

In addition to fighting, chickens were also important for activities of the spirit and were utilized in religious rites, including fortune-telling. The practice termed haruspicy in ancient Greece was a way to divine the future by slaughtering a chicken (or other small animal such as a goat or sheep) and examining its entrails, particularly the liver, for signs to foretell coming events. Blood offerings to the gods were highly desirable public displays of fealty, and chicken sacrifice was common to seek guidance prior to a battle or other challenge.

‘Hen Fever’: Chicken’s Rise, from Food for the Poor to a Plaything of Royalty

All this talk of chicken innards, and yet chickens were not yet viewed as edible. Surprising as it may seem to modern protein seekers, neither the meat nor eggs of the chicken was consumed by humans for thousands of years after it was domesticated. Chickens performed functions in ancient cultures that didn’t have anything to do with scrambled eggs or fried drumsticks . . . until the Greeks. No earlier than 1500 B.C.E. did humans first become accustomed to the taste of chicken meat. While it was sometimes consumed, in small portions, after a religious ceremony, the wide-scale consumption of chicken as food started with poor people in Greek lands. Later, as the Romans expanded their empire, chicken meat was exported throughout the realm as a cheap and plentiful food source.

Which came first, the chicken or the egg may be an unsolvable riddle, but we can say with some assurance which was eaten first. Though it wasn’t deemed to be haute cuisine, chicken meat made it to the palates of human beings prior to the advent of the “incredible edible egg.”

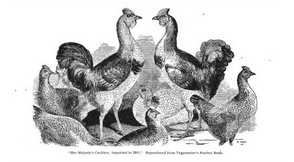

These Cochin chickens, imported from China in the 19th century, were highly favored by Queen Victoria of England.

(Source: Biodiversity Heritage Library)

Hens eventually came to be prized for their prowess in egg-laying, and even came to the attention of the crowned heads of Europe. Queen Victoria of England was given an egg-laying chicken from China. She was so delighted with it that she kicked off a British, and eventually European, craze for collecting “layers” and their eggs. It was greatly desired, and deeply appreciated, to receive a gift of an egg from one of Victoria’s layers. Egg-trading became quite the frenzy, and the period came to be known as the time of “Hen Fever.”

The fashion of exchanging eggs seems to have combined with the Christian tradition of decorating eggs to celebrate the season of Lent and Easter in Russia in the mid- to late-1800s. A fine jeweler in St. Petersburg, Russia, taking note of the Russian imperial family’s propensity to exchange decorated eggs, was given the task by a royal relative of creating bejeweled “eggs” to serve as gifts from one Romanoff family member to another.

Peter Carl Fabergé crafted these eggs under a special arrangement to supply them to the tsar’s family. Part of the desirability of these “Fabergé eggs” is their scarcity. Fabergé abruptly ended his jewelry-making venture for the Romanoffs at the outbreak of the Russian Revolution of 1917, and a mere 50 or so of the eggs exist today.

The Enduring Popularity of Chicken

The allure of chickens – and their appetizing product, eggs – has only grown since the early 20th century. Now, worldwide, 50 billion chickens are used annually for meat and eggs. Two distinct variations of chicken – layers and broilers – have been bred for specific purposes and, as they say, form is function. Layers are lean, while broilers have very large breasts and are meatier overall.

Alternatives to factory farming, such as this free-range chicken farm, are growing in popularity. (Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture, via Wikimedia Creative Commons)

Factory farming is a fact of life in the U.S. and most industrialized nations. Chickens are raised in tight quarters and are given hormones to produce big eggs and bigger capons. But since the end of the 20th century, healthier practices have become more popular. Today, in the U.S., a full quarter of all chickens raised are so-called “free-range” (or, more accurately, “pasture-raised”) chickens. This means they have open space to roam and are not confined in an enclosure for 24 hours each day, as are most, less fortunate, factory chickens.

What do you hear when a rooster greets the day? Well, it depends on your native language. In English, the rooster sings, “cock-a-doodle-doo.” But in Portuguese the sound is “cucurucu.” In Italian, it’s “chicchirichi,” and in Turkish, “git-git-giddak.”

Maybe it wasn’t always this way, but their popularity – not only as food, but as pets! – is now undeniable. Maybe one day they’ll even solve world problems. In an episode of the popular American adult animation show The Simpsons, “The Greatest Story Ever D’ohed” (2010), Homer Simpson has a vision after becoming stranded and dehydrated in the desert around the holy city of Jerusalem. Once he makes his way back to civilization, he has a message for the masses assembled around him. It’s a message of peace – plus one additional ingredient:

“Let us celebrate our commonalities. Some of us don’t eat pork. Some of us don’t eat shellfish. But we all eat chicken. . . . So spread the word: Peace and Chicken.”

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title image: Chicken by MabelAmber via Pixabay.