What do you know about Hawai’i and its pre-statehood history? Are you aware that the islands’ last monarch, Queen Lili‘uokalani, was forced to give up her throne by American interests, backed by the U.S. Marines? Since then, there has been a long-standing tradition of resistance to U.S. power, and even to statehood itself, among many native Hawaiians. How did these aspirations arise, and how will Hawai’i’s future be determined?

◊

A Coup in Paradise

Perhaps no moment was more pivotal and portentous to Hawai‘i’s legacy than this one:

The dawn of January 17, 1893, could not come soon enough for Queen Lili‘uokalani. Her night had been restless, and her concerns lay heavy on her mind. The previous day, January 16th, had brought unprecedented schisms into stark relief. She had been informed that professed enemies of the monarchy – who called themselves the “Committee of Safety” – were arming themselves to an extent that suggested self-protection was not the goal. Rather, violent conflict seemed to be imminent.

The Queen’s marshal and members of her armed guards were dispatched to confront and arrest the Committee members, but before they even arrived – and witnessed the distribution of arms themselves – word arrived from the Queen’s quarters to stand down. Rather than arrest the 13 or so men, confiscate their arms, and charge them with sedition, the guards were informed to observe but take no action. The Queen and her advisers were afraid of what would happen should violence break out.

In the early hours of the 17th, the Queen knew that an event was soon coming that would drastically change her relationship to her beloved home, the home of her ancestors: The island nation of Hawai‘i.

Hawaiian Sovereignty vs. American Protection

Queen Lili‘uokalani’s fear for her homeland was well-founded. Within hours of ordering her guards to withdraw, members of the so-called Committee for Safety, flanked by about 500 U.S. troops, entered the palace grounds and placed the queen under house arrest. Just five years earlier, in 1887, the so-called “Bayonet Constitution,” which limited her powers and restricted voting rights for native Hawaiians, was imposed by wealthy landowners (called haoles because of their non-native backgrounds). And later, in 1898, Hawai’i was annexed by the United States as a protectorate. In 1959, it became a full-fledged state.

Queen Liliuokalani, c. 1898 (Credit: George Prince via Wikimedia Commons)

In the runup to statehood, many landholders, surprisingly, were opposed. They feared that statehood would force them to abandon their highly lucrative practice of importing large numbers of foreign workers to toil on their plantations. In the end, however, industry continued to thrive after statehood.

You might think that statehood and the extensive ties that have grown between the islands and the mainland ended Hawaiian independence once and for all, but the fact is the dream of a return to sovereignty has not died. Since the 1960s and ’70s, as revealed in director Luis Castro’s documentary Hawai‘i: The Stolen Paradise, groups have formed to organize and promote a return to an idealized Hawaiian past.

Some groups have as their goal the expulsion of American interests from the island and a restoration of Hawaiian self-rule. Others, inspired by the mainland’s American Indian Movement, want native Hawaiians recognized by the U.S. government as an indigenous group and given political sovereignty in the same way that Native Americans have limited self-rule.

Hawai‘i’s Unheralded History of Independence

The islands that comprise Hawai‘i have been inhabited for more than a millennium, most likely originally by seafarers from Tahiti. Over centuries, interconnected but independent societies developed on each of the main islands in the archipelago, and these societies evolved into separate kingdoms until the end of the 18th century, when Kamehameha of O‘ahu began a quest to unify the separate island kingdoms in often-bloody conflicts.

By this time, the islanders were accustomed to visits by Western trading ships, which began with British explorer James Cook in 1778. In fact, historians believe that Kamehameha was aided in his efforts to unify and rule the islands by weapons he received from Cook.

Over the course of the 1800s more trading ships arrived, bringing with them Hawai‘i’s first Western settlers. These immigrants to the islands were attracted to the plentiful, rich land and the potential for production of sugar, fruits, and other tropical goods, including sandalwood.

The Non-Natives Are Restless

As settlers reaped financial rewards by shipping Hawaiian products to eager mainland traders and consumers, the transformation of undeveloped land for crops proceeded apace – and immigration increased. Migrants from around the world arrived en masse to work the land and build infrastructure.

By the mid- to late-19th century, there were quite a few wealthy American landowners on the islands who had set up their property in a manner influenced by the plantations of the American South. These new Hawaiian plantations were very lucrative – for their owners – and the American businessmen began to desire more return on their investments.

Christian missionaries, too, were enthusiastic about their prospects in this new land, and they were well received by American landowners there, if not by the native population. Missionaries set up churches, schools, and hospitals but undermined their “good works” by banning Hawaiian dress and, infamously, the Hawaiian language from being taught or used.

The Americans who resided in Hawai‘i during this era were insistent on forging continuously closer relations with their trading partners on the U.S. mainland. They were not going to be discouraged or deterred by the inconvenient reality that they were operating in a sovereign, internationally recognized nation. Soon enough, the bloodless coup against Queen Lili‘uokalani was launched, and the American land-owners got their way.

The Destruction of Native Culture and the Rise of the U.S. Military

Native Hawaiians not of European descent were hit hard by the change in status. They became second-class citizens ruled by haoles who controlled the government. Their lands were appropriated, and they were denied voting rights. In 1896, the new, non-native government that overthrew Queen Lili‘uokalani officially banned the use of the Hawaiian language in education and government.

Once the Americans secured their hegemony, the U.S. military was eager to establish bases. This led to strategic superiority in resources and armaments, and extended an empire that now spanned both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

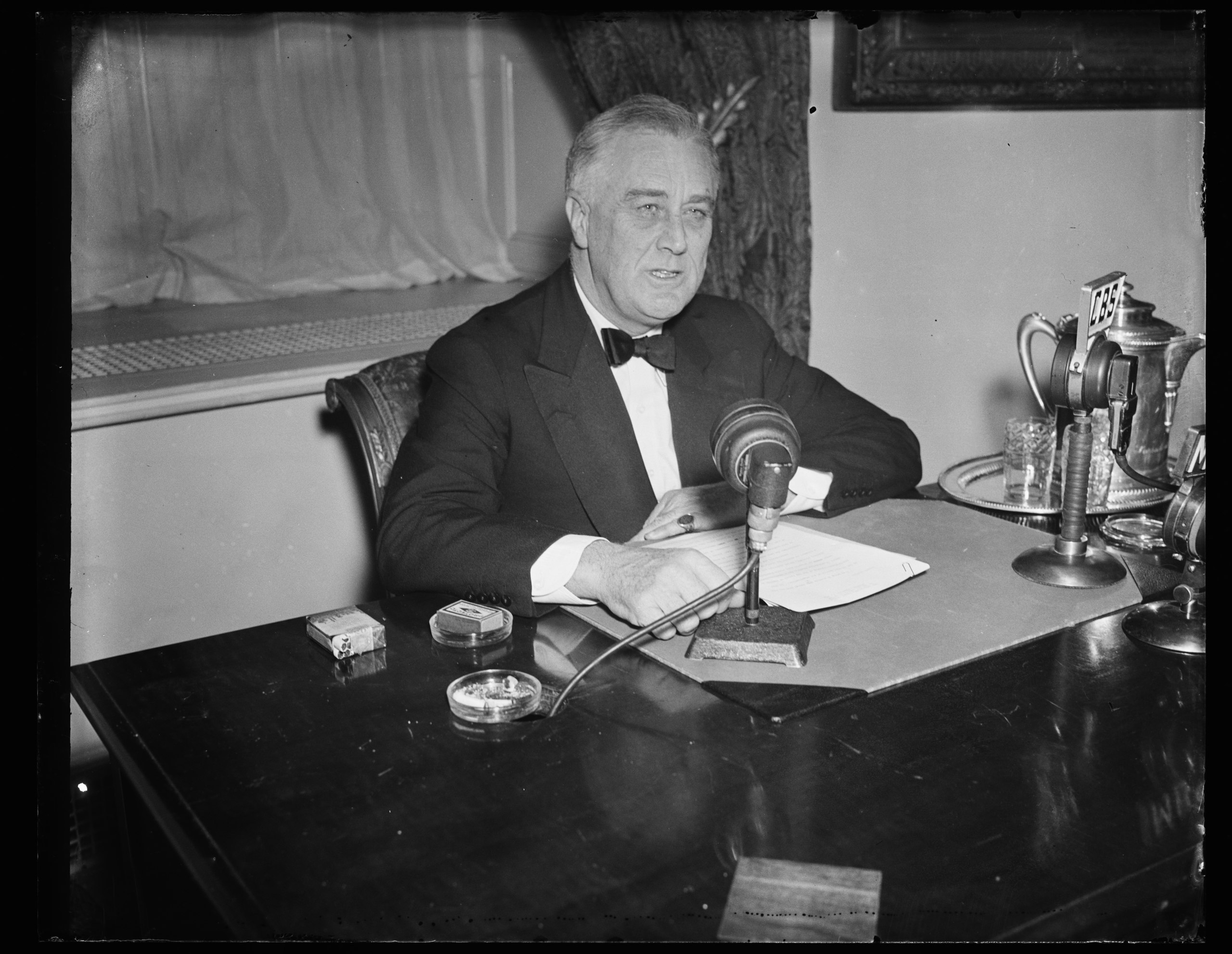

Pearl Harbor, which had been an important welcoming port for traders and visitors alike, was entirely taken over by the U.S. Navy. The scope and scale of the naval installations there expanded substantially over the early decades of the 20th century. The U.S. Army was amply represented, as well. By 1939, during the build-up to war under President Franklin Roosevelt, there were more than 50,000 military personnel stationed in the territory.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt radio broadcast, 1933 (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

RECOMMENDED: THE WHEELCHAIR PRESIDENT

During World War II (and after), military exercises were virtually continuous. The armed services needed not only the open ocean for these training activities, but also land. So they occupied property on numerous small islands and atolls where they operated.

Over the years, the buildup of military waste and spent munitions transformed some islands from breathtaking beauty to a state of total despoilment, off-limits for safety reasons to Hawai‘i’s native population.

The entire Territory of Hawai‘i, including all its islands, was declared to be under martial law in December 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This existing government under its governor was suspended, and martial law was not lifted until April 1944.

A Call to Restore Self-Determination

In the aftermath of the Vietnam War and the many other cultural upheavals of the 1960s and ’70s, there was growing unease with the status quo among many Hawaiians of native descent. They began to openly counter and challenge the military-industrial takeover of the islands that had started so long before, back in the days of Lili‘uokalani. Their demands were many, and included:

- The return of self-rule to the islands, including setting up a new government structure

- The removal of military waste and munitions from the islands

- The return of military-held lands to the people for restoration

- Secession from the U.S. and the return of sovereignty for this island nation

Despite a contentious relationship with both the government and the military, the movement has stayed active from the 1970s to now. And it has not been without its successes. In the notorious case of Kaho‘olawe Island, which the military had appropriated for exercises, sustained protests in the 1970s and ’80s – and the deaths of two protesters – led to the military abandoning the island (unrestored, incidentally) in 1990. This allowed native Hawaiians to return legally to the island, which was historically revered as a sacred site and used for religious ceremonies.

There are 768 military-contaminated sites across the Hawaiian islands.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton signed what has become known as the Apology Resolution, which acknowledges that the overthrow of the queen in 1893 and the subsequent annexation of the islands were illegal acts. In addition, Hawaiians of native heritage have won the right to organize a representative political entity that they refer to as the “Lawful Hawaiian Government.” This unofficial governing body promotes native Hawaiian culture, the traditional hula, and the Polynesian language spoken on the island prior to 1896.

But what comes next?

An Uneasy Peace (Capitalism Wins Out)

Despite these tentative steps toward self-rule and sovereignty, it’s highly unlikely that the U.S. will be losing a state anytime soon. The ties between Hawai‘i and the mainland are just too strong. Tourism would take a huge hit – particularly among state-siders – if the islands were not an American state. But it’s just not possible to underestimate the passion and tenacity of the native Hawaiians involved in this cause. They may never gain true sovereignty, but they have achieved self-respect for themselves and certain concessions from the government – and for now that’s enough to keep them motivated. Queen Lili‘uokalani would be proud of them.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

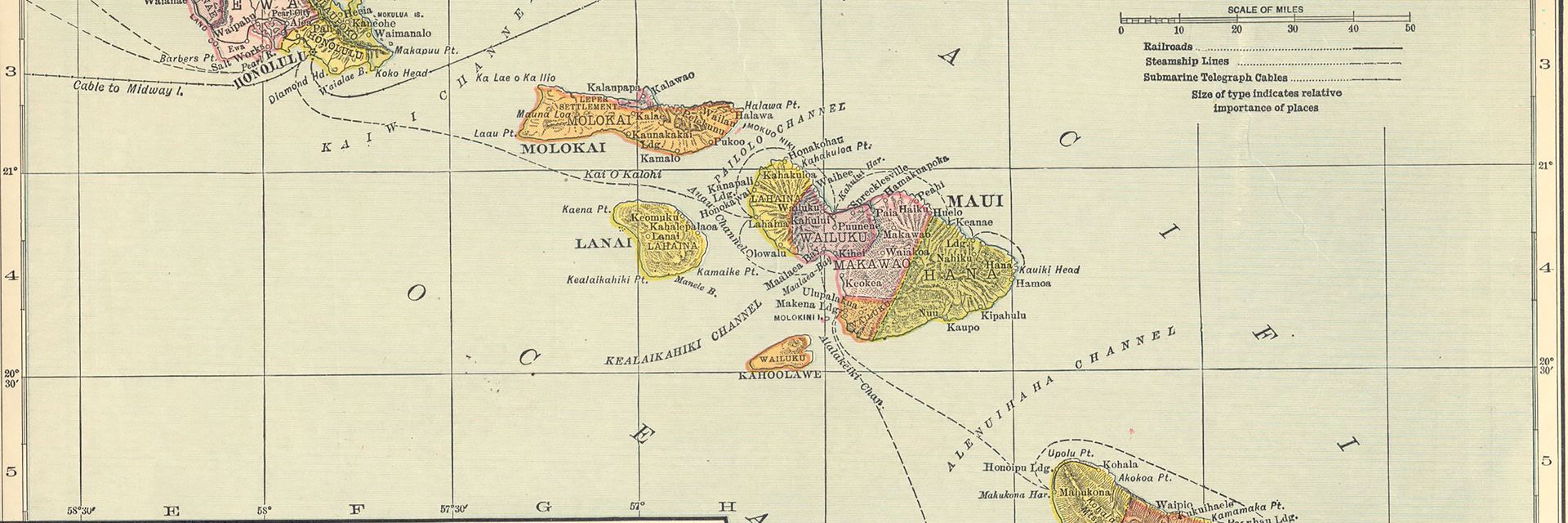

Title image: Hawaii, Hammond 1910 Map. (Credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)