The revolution of wireless telegraphy interconnected the world in ways previously unimaginable.

◊

Here we are in the 21st century, taking for granted the myriad ways we connect without the aid of wires – Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, and who knows what we’ll come to rely on in the future. When we think about how all this wireless interconnectivity got rolling, a good starting point is to consider the contributions of Guglielmo Marconi, the physicist and inventor who revolutionized communication by developing the first effective system of wireless telegraphy more than a century ago.

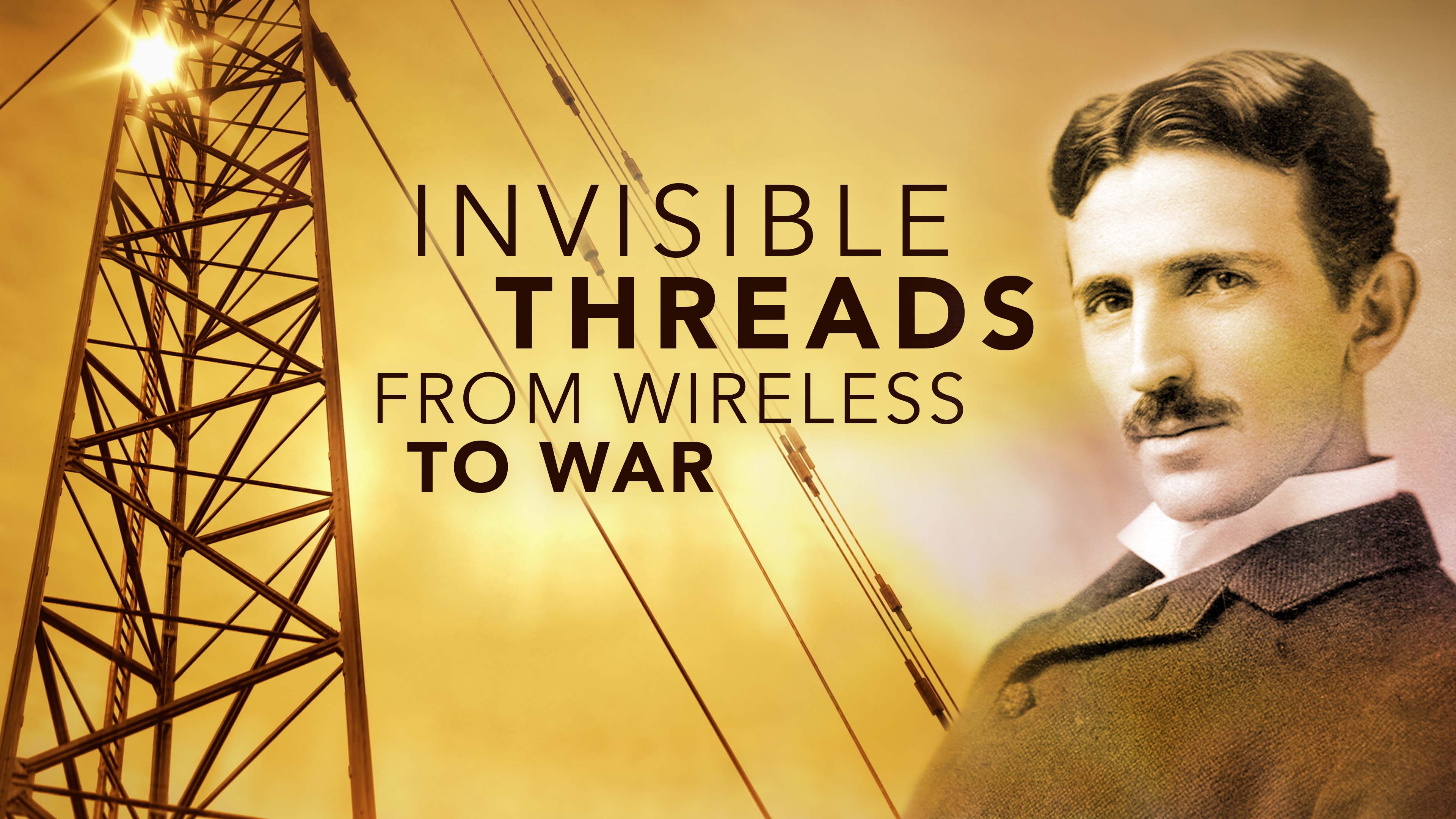

For more on Marconi and others who contributed to the development of wireless technologies, check out Invisible Threads: From Wireless to War on MagellanTV.

Marconi’s Early Life and the Invention of Wireless Telegraphy

Born in 1874, Marconi was of Italian and Irish descent. From a young age, he was fascinated by physical and electrical science, showing a particular aptitude for experimentation. His education, a mix of private tutoring and formal schooling, was complemented by his own self-directed study of the works of scientists such as Heinrich Hertz and James Clerk Maxwell.

Marconi was fascinated by the possibility of transmitting telegraph messages without depending on elaborate and costly networks of wires strung from poles and wrapped into cables to stretch across the floors of oceans. He was particularly intrigued by the idea of using electromagnetic waves to transmit messages after learning of Hertz’s experiments with radio waves.

In 1895, Marconi began his groundbreaking work. He began his experiments at his father’s estate in Italy. The first apparatus consisted of a transmitter and a receiver, using rudimentary antennas and a system of keyed interrupters to send messages in Morse code over a distance of 1.5 miles. With this success, he joined the ranks of late-19th/early-20th century inventors like Thomas Alva Edison, Nikola Tesla, and the Wright brothers.

Marconi Expands His Horizons

Marconi’s ambitions grew, and, in 1896, he traveled to England, where he gained the interest and support of the British Post Office. By July 1897, he had established a wireless communications link between points about 12 miles apart; only a few months later he sent messages 34 miles across the Bristol Channel.

Fame and recognition followed just before the turn of the century, in 1899, when Marconi succeeded in transmitting messages across the English Channel between Britain and France. Naturally, this accomplishment fueled the pace and scope of his work.

Marconi’s most remarkable achievement came in December 1901, when he transmitted wireless signals 2,100 miles across the Atlantic Ocean, from Poldhu in Cornwall, England, to St. Johns, Newfoundland in Canada. In only two short years, signal transmission had leapt from international to intercontinental, opening the way for wireless communication over extremely long distances and practical use for many purposes.

Marconi team preparing to fly kite with receiving antenna, St. John’s, Newfoundland, 1901 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Recognition and Legacy

In the following years, Marconi continued to improve his system. He developed the magnetic detector for telegraphs (a significant improvement on previous detectors) and introduced the concept of tuned or syntonic wireless telegraphy. In 1909, he and Karl Ferdinand Braun were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their contributions to wireless telegraphy.

Not surprisingly, military applications of the new technology took center stage in the run-up to the First World War. The competition among nations included cloak-and-dagger operations, a story told in fascinating detail in MagellanTV’s two-part documentary Invisible Threads: From Wireless to War.

Guglielmo Marconi passed away in Rome, in 1937. His work created the foundation for modern radio technology and opened the door to the endless potential of wireless communications, earning him a place in the pantheon of the greatest inventors and scientists of his time.

Ω

Guglielmo Marconi with wireless transmission equipment in 1890s (Credit: LIFE Photo Archive, via Wikimedia Commons)