This year, 2020, marks the 50th anniversary of a milestone in the progress of the feminist movement, a political event that demonstrated the power and reach of feminist organizing around social goals. Along with other organized feminist street protests in that era, the event, the Women’s Strike for Equality, galvanized the movement and even resulted in President Nixon declaring the date of the strike – August 26 – as National Women’s Equality Day.

◊

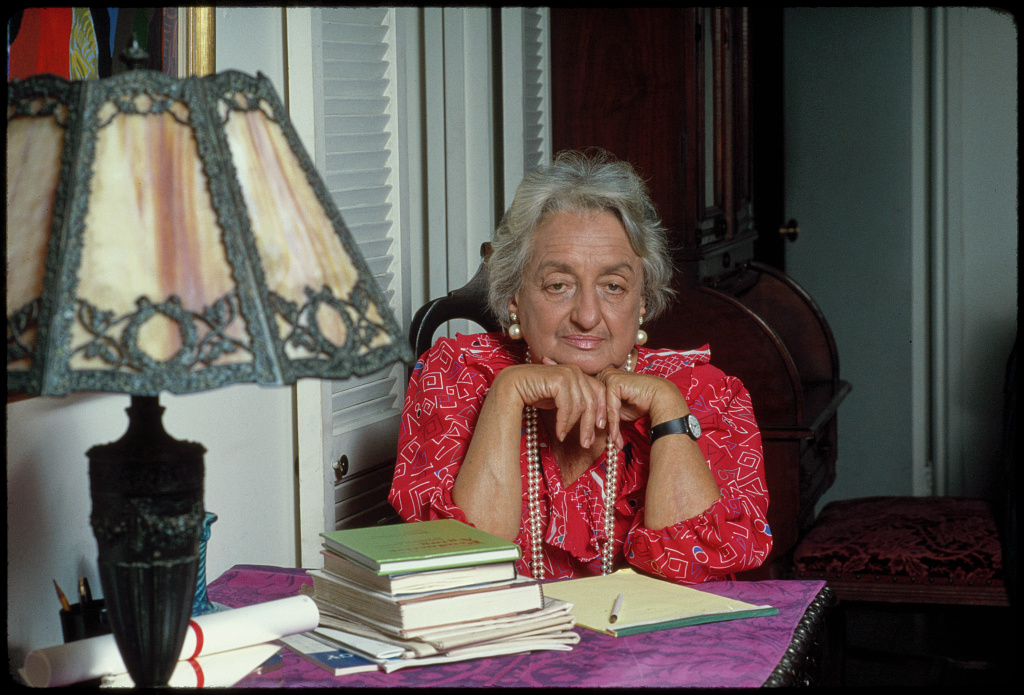

“This is not a bedroom war, this is a political movement,” proclaimed Betty Friedan from the stage of Manhattan’s Bryant Park where, by some estimates, as many as 50,000 women had gathered for a rally following the Women’s Strike for Equality march down Fifth Avenue on August 26, 1970. It was the 50th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the United States, and a prime day for women to exert their power.

Betty Friedan, whose 1963 book The Feminine Mystique can fairly be said to have sparked “second-wave” feminism to life, was a co-founder of the National Organization for Women (NOW) and had been the first president of the group. At the end of her term as president she had called for the strike, echoing a section of her well-known and well-read book.

(Source: Public Domain, via Wikipedia Commons)

Now, at the fruition of her call to action, after five months of high-stakes planning and strategizing, Friedan saw her vision come to life. A large cadre of women, along with some male supporters, gathered at 59th Street and Fifth Avenue, forming huge waves of people marching nearly 20 blocks southward on Fifth through midtown Manhattan to their goal, Bryant Park.

At the podium in the park, Friedan gathered with her fellow speakers, including Gloria Steinem, Bess Myerson, and Bella Abzug. In her speech, Friedan reiterated her condemnation of the undervaluing of women in society and demanded changes to allow women to compete on a level playing field for opportunity in many fields, from the office to the kitchen.

Not everyone who listened that day agreed with the women’s demands. On CBS News that evening, commentator Eric Sevareid paternalistically noted that “most men, and a great many women, feel baffled. . . . The instruction manual for this has not yet been written. It is . . . impossible to separate one’s personality from one’s sex.”

Empowering Women to Set the Conversation: “No More Miss America!”

Indeed, many men did feel “baffled,” and not only those in the media. While “women’s liberation” used the framework of, and shared strategies with, those who protested racial discrimination and the Vietnam War, even many of the leaders of those protest movements were unfamiliar with – and resistant to – a women’s mobilization movement.

Most protests of the time, including those in favor of civil rights and opposed to the Vietnam War, were well-attended by young women. And the more theatrical protests – such as the Yippies nominating a pig for president outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention – offered lessons to nascent feminists, who were often turned off by the male domination of political groups and the male chauvinist posturing of protest leaders.

One such leader was Stokely Carmichael, of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), who infamously declared, “The only position for women in SNCC is prone.” In response, women activists started banding together, developing their own agendas and priorities for protests. Mild-mannered picket lines were out, replaced by more aggressive, dramatic demonstrations demanding equal rights for all.

The first of numerous large-scale feminist street protests was the controversial rally and demonstration against the Miss America pageant of September 1968. That protest took place outside – and inside – the annual Miss America contest in Atlantic City, New Jersey, provoking jeers as well as cheers.

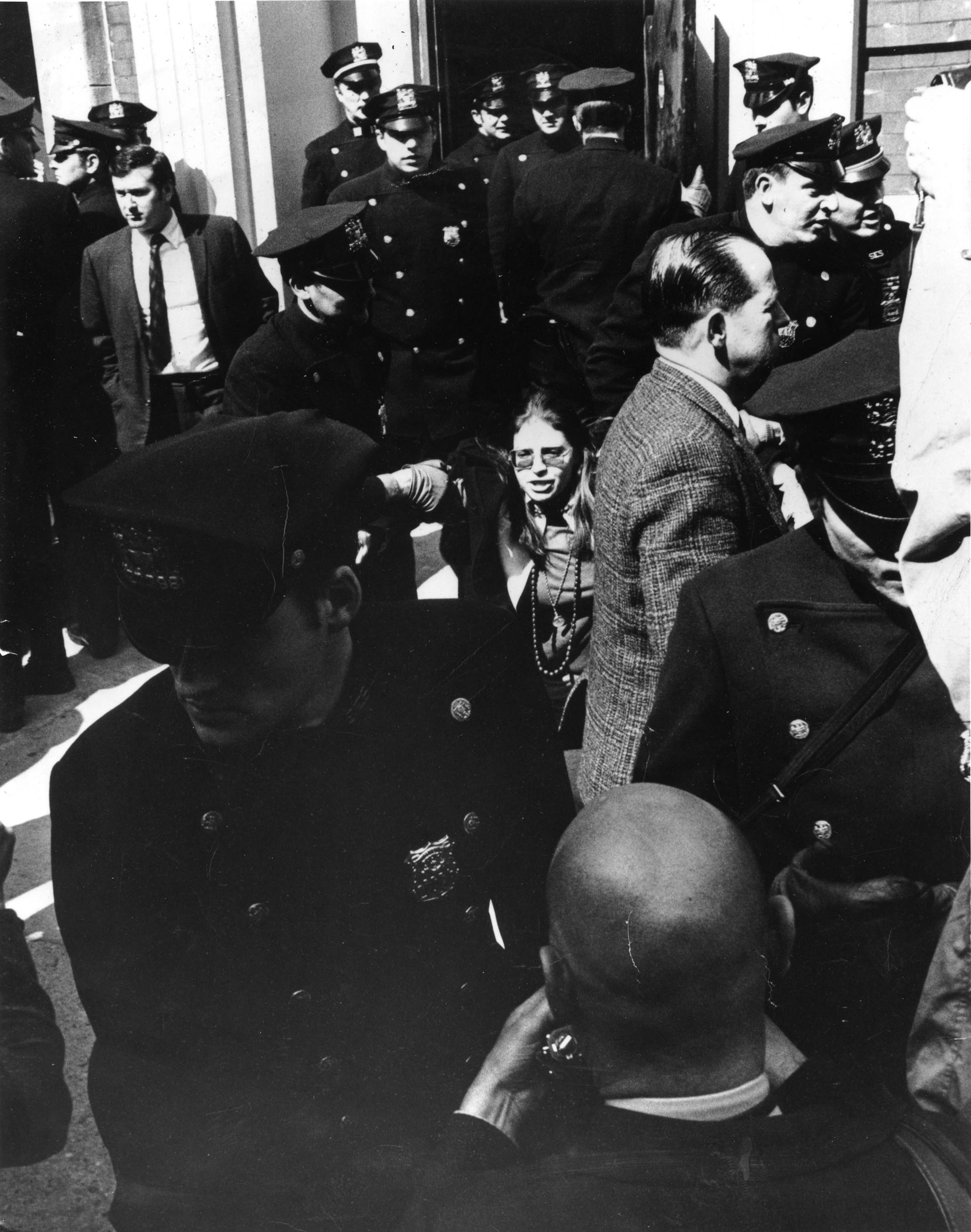

The Miss America protests were largely the brainchild of radical feminist Robin Morgan, a veteran of the 1960s movements against racial segregation and the Vietnam War. Morgan centered her focus on women’s issues in part because she found the antiwar and antidiscrimination movements to be stultifyingly sexist, with women shunted to the sidelines.

Robin Morgan being placed under arrest (RMBMphotos, via Wikimedia Commons)

Morgan and her fellow members of New York Radical Women envisioned a political – and theatrical – protest that would capture the attention of the public and the imagination of like-minded women everywhere. Their critique of the Miss America pageant was that it was sexist to the root, dedicated to objectifying women like pieces of meat and focused on a vision of femininity that was outdated and dangerous to women. Beyond that, women criticized the racist policies of the pageant, which excluded black women, and women of color generally, from competing in the pageant.

Women’s Power on the Atlantic City Boardwalk – and the Origin of the Myth of the “Bra-Burning Feminist”

With a flair for street actions gained from radical “guerrilla theater” performances in anti-Vietnam War protests, the women organizers of the anti-Miss America event aimed for maximum visibility to their demonstration. They anticipated being covered in local papers around the country to spread their message.

The protest action had three elements:

- A boardwalk protest outside Atlantic City’s Convention Center, where the Miss America pageant was held; protesters held placards and enlarged photo images showing a woman’s body marked like cattle. A sheep was paraded through the area, representing the dehumanization of women into livestock for judging and grading.

- The “Freedom Trash Can,” into which women tossed objects that represented the oppression of women, including high-heeled shoes, bras, girdles, pots and pans, and Playboy magazines. Despite the enduring belief that feminists burned their bras at this demonstration, no such burning took place – the Atlantic City police had refused the organizers’ request, and the protesters complied.

- Women unfurled a banner inscribed with “Women’s Liberation” inside the theater during the announcement of the winner of the competition. Before the activists were ejected, they had time to chant “women’s liberation” as well as “no more Miss America!”

Despite the serious aims of this protest, its theatricality led some in the male-dominated press and media to ridicule the protest participants. In particular, the spectacle of the “bra-burning feminist” – despite it never having happened – lasted for decades as an antifeminist epithet.

Protesting Ladies’ Home Journal’s Male Editorial Leadership

Another powerful – and photogenic – protest that attracted many of the same activists took place on March 18, 1970, in the offices of one of the most widely read and influential “ladies’ magazines” in the U.S., the Ladies’ Home Journal (LHJ). Activists drawn from NOW, the New York Radical Women, and the Redstockings, concerned about the messaging of media directed at American women, targeted LHJ for what they deemed its sexist attitudes as well as its virtually all-male editorial and advertising teams.

Highlighted in the protest action were the magazine’s traditional emphasis on feminine beauty, and its encouragement of women to please their men through self-sacrifice. One prominent feature in LHJ, called “Can This Marriage Be Saved,” drew women activists’ scorn for placing the responsibility for keeping a marriage together squarely on women’s shoulders, and for its frequent advice for women to place their needs second to those of their husbands.

Over 100 women protesters entered the New York City offices of LHJ for a “sit-in” and “teach-in” on women’s issues and how to redress generations of men’s oppressive advice for women. Though rebuffed initially by LHJ’s male editor, John Mack Carter, the women made it known they were prepared for a long occupation. Eleven hours later, the editors conceded that the protesters had a point, and offered to let them develop their own section to be inserted into the pages of a future LHJ.

The women’s section, pointedly, had a feature titled “Should This Marriage Be Saved,” as well as articles on educating female children, and on feminism and childbirth. The publication month of the “raised-consciousness” edition of the Ladies’ Home Journal coincided with the Women’s Strike for Equality – August 1970. Dispiritingly, letters published in a subsequent issue of LHJ ran significantly against the inclusion of these feminist topics, and virtually all the letter-writers were women.

Organizing the 1970 Women’s Strike for Equality

When, at her farewell address to NOW, Betty Friedan proposed the Women’s Strike, the organization became an official sponsor of the event, and Friedan gathered enough fellow activists to her cause to create an organizing committee. This group set about pushing a women’s rights agenda that was further to the left, and more socially progressive, than the mainstream attempts at conversation and conversion from within supported by NOW’s more traditional organizers.

Betty Friedan (Credit: Bernard Gotfryd/Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

After many discussions, often using as non-hierarchical and decidedly non-patriarchal methods as possible – women seated on the floor in a circle, without a named leader – the strike organizing committee developed three fundamental “demands” that, taken together as a platform, were intended to empower women and to provide a pathway to gender parity, even equality, with men.

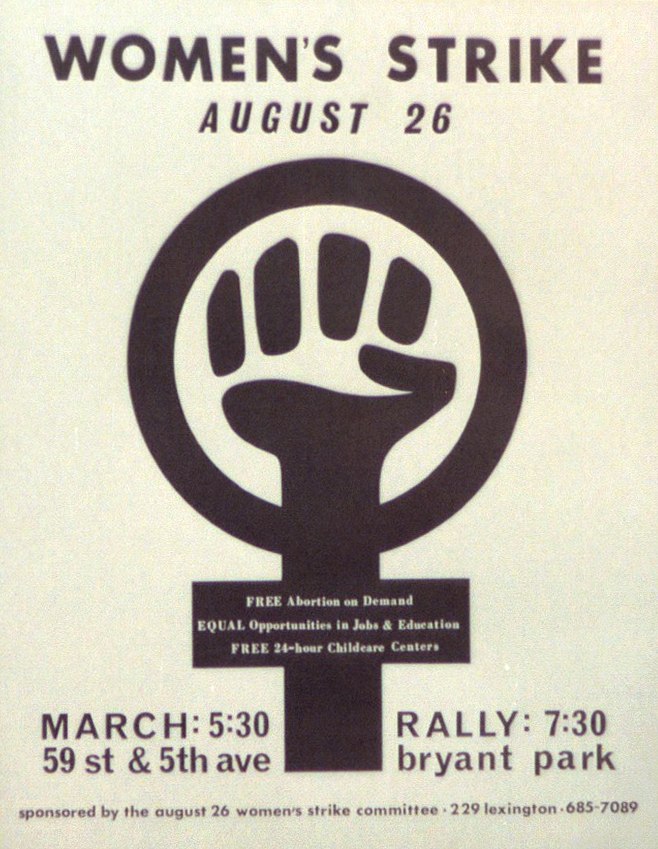

These three goals were:

- Free abortion on demand;

- Equal opportunities in jobs and education; and

- Free 24-hour childcare centers.

Knowing that these goals were more “in your face” than earlier NOW platforms designed to lobby centers of male dominance in government, media, and business, Friedan and her co-organizers worked diligently to expand the strike’s supporters to include men as well as women – and conservative as well as liberal voices.

NOW, the National Organization for Women (emphasis added), was never intended as – and never was – a women-only group. Men were among its earliest supporters and members, including at least three men among its 49 “co-founders.”

What Women Want: The Wide Scope of the Women’s Strike Objectives

The three primary goals were not the strike’s only objectives. In addition, Friedan and her co-organizers wanted to use the Women’s Strike to demonstrate the value of “women’s work,” whether in the professional or in the domestic realm, and whether the labor was paid or unpaid.

Other objectives of the march and rally were to demand more political rights for women as well as to demand an end to sexism in marriage, and to win full equality with men in both marriage and divorce.

At that time, women working outside the home earned about 60 percent of what men did for the same work. In addition, women had virtually no economic rights: It was, for example, challenging if not impossible for a woman, married or not, to gain financial credit in her own name. It was the man who held the property rights and the economic power.

Pulling Off the First Nationwide Action Led by Feminist Activists in the U.S.

The August Wednesday of the Women’s Strike march and rally was square in the middle of the Dog Days, and the sultry weather conditions challenged the protesters who had committed to participate. Though the strike was largely symbolic – the event was scheduled to begin at 5:30 p.m., after most women’s work-shifts had ended – attendance would gauge NOW’s reach into the general populace and serve as a harbinger for future actions.

Betty Friedan need not have lost sleep; her vision was more than rewarded. The marchers were granted one lane of Fifth Avenue to commandeer as they hiked from midtown Manhattan down to Bryant Park, but so many women were in the street that they took over the entire thoroughfare. The size of the crowd made it the largest women’s public gathering since the days of the American suffrage movement.

The crowd in Bryant Park swelled as speakers addressed the assembly. Prominent women from many walks of life spoke. Activist and future politician Eleanor Holmes Norton implored, “Give us the right to compete. Give us the right to live, the right to a job regardless of sex.” Feminist author Kate Millet proclaimed, “Today is the beginning of a new movement. Today is the end of millenniums of oppression.” And lead organizer Friedan advised, “Man is not the enemy; man is a fellow victim.”

Actions took place not only in New York City but in a variety of locations around the country. In Washington, D.C., women marched on Connecticut Avenue and lobbied for the Equal Rights Amendment. In Detroit, there was a targeted protest for improved women’s working conditions at the city’s largest newspaper, the Detroit Free Press. And in Los Angeles, women held a candle-lit vigil for women’s rights. Internationally, women also voiced support in Paris, Amsterdam, and elsewhere.

Bella Abzug (Source: Library of Congress, via Wikimedia Commons)

Within three years, prodded into action by U.S. Representative Bella Abzug, President Richard Nixon declared the anniversary of the event, August 26, to be National Women’s Equality Day.

Reactions and Backlash Reveal the Work Still to Be Done

Not all observers were aligned with the women’s movement. Time magazine summed up its reporting on the event by calling it, “some of the best sidewalk ogling in years.” Male pundits and commentators opined that women had had their say, and now it was time to return to the traditional order. Conventional views on women and femininity were rocked to the core that day, to the dismay of many men and some women. One such woman was right-wing gadfly Phyllis Schlafly, though it would not be until later in the 1970s that she would zero in on women’s rights with her opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment.

Despite having clear aims for the protest, the organizers of the Women’s Strike for Equality did not actually achieve their three most significant goals: free abortion access, equal opportunity in employment and education, and free 24/7 childcare availability. The 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade improved access to abortion and family planning services, but its cost and its uncertain availability from state to state make it less definitive a success than had been envisioned.

Title IX, which passed into law in 1972, enabled women to access educational opportunities with federally mandated penalties for discrimination; on the other hand, women’s wages in American employment still lag unconscionably behind men’s. While improved since 1970, the current earnings gap has women earning just over 80 cents to each man’s dollar. And there is no national policy on affordable – let alone free – access to childcare for the working woman.

While we celebrate the centennial of women’s right to vote in the U.S., and the semicentennial (50 years) of the flowering of second-wave feminism in the Women’s Strike, the old adage still rings true: A woman’s work is never done.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title image: National Organization for Women (NOW) founder and president Betty Naomi Goldstein Friedan with co-chair and lobbyist Barbara Ireton and feminist attorney Marguerite Rawalt via Wikimedia Commons.