Evolution is a process of incredible growth and change. Species are constantly dying off and coming into being, adapting into myriad forms. Over vast stretches of time, there have been many planet-wide upheavals. These are termed “mass extinction events,” defined as times when the rate of species extinction is greater than the rate of species creation. While scientists debate the exact number of such events, there is general agreement that Earth has experienced five “major extinction events,” in which over 75 percent of species went extinct. Now, many believe, human activity has led us into a sixth catastrophic loss of species, the Holocene Extinction.

◊

When Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859, there was no way he could have known just how long evolution had been at work – the billions of years of biological change cascading throughout geological history. How would he have guessed that the finches he studied so diligently in the Galapagos were descended from towering reptiles, spread across shifting continents. It would have taken a madman to imagine the early Arthropods, including massive “sea scorpions” over eight feet long, hunting beneath the surface of vast oceans. All of this from the most minimal of beginnings when, 3.5 billion years ago, microscopic creatures such as bacteria inhabited the oxygen-rich oceans, so small they were practically indistinguishable from inanimate molecules.

Not only was Darwin correct about evolution, he also drew remarkable conclusions about humanity’s impact on the natural world. He writes in Origin: “Man selects only for his own good; Nature only for that of the being which she tends.” While Darwin was originally referring to domestication and selective breeding, the quote takes on a double meaning in the modern era: Humanity benefits only itself, while life around it suffers. By the very nature of our advancement for our “own good,” nature’s attempts to tend to itself are constantly interfered with.

The species that have been lost forever because of human activities are victims of a mass extinction event known as the Holocene Extinction (sometimes referred to as the Sixth Mass Extinction or the Anthropocene Extinction).

The Holocene is potentially catastrophic, and it’s not the first event of its type in Earth’s history. To understand what the Holocene is, and what makes it so devastating, you first need to look back at the previous five major extinction events: massive changes which collectively wiped out 99 percent of all species that have existed on our planet.

Ordovician Extinction: 541 — 443 Million Years Ago

Our journey back through time begins with the Cambrian Period, which saw the first vertebrate life on Earth. The microscopic multicellular organisms that were the first living things spread across the planet wherever water collected, diversifying and growing large enough to be visible to the human eye.

The beginning of the period was marked by the Cambrian Explosion, with intense species diversification occurring across the planet. This growth was driven by the increasing oxygen in the atmosphere and rising sea levels, which created warm shallow-water environments. The increased oxygen also led to thriving plant life, particularly algae, which blanketed the sea floor in these new habitats. Because of this steady supply of food for smaller organisms, life grew in diversity but not size, measuring in inches if not smaller.

Most of the fauna from the Cambrian period have forms reminiscent of modern crustaceans like shrimp and lobsters. Although the vast majority were tiny, some like the recently discovered Titanokorys gainesi could grow to over a foot, making them titans at the time.

Moving into the Ordovician, many species evolved in more niche environments, with forms that were as bizarre as they were beneficial. Take the aptly named Hallucigenia, with its multitude of protruding spines, theorized to function as protection. The remarkable Opabinia with its projecting proboscis, used for hunting smaller creatures like the plentiful ancestors of shrimp. And lastly but certainly not least insane-looking: Kootenayscolex barbarensis. Barbensis was a type of bristle worm, aptly named for the hairs covering its body, which it used for locomotion.

Modern bristle worm, an ancestor of Barbensis (Credit: Alexander Semenov/Creative Commons license, via Flickr)

While shallow-water areas were great incubators for creatures that would have left H.P. Lovecraft feeling inspired, they wouldn’t last forever. The Ordovician ended with a continent-sized ice cap developing on the South Pole. Global temperatures cooled and water levels fell; the warm shallow environments were quickly destroyed, leading to 86 percent of species going extinct.

Late Devonian Extinction: 444 — 358 million years ago

With the Cambrian and Ordivician periods ended and dramatically different conditions on this colder Earth, life began to rebuild its marine diversity. The next two periods, the Silurian and Devonian, also gave rise to larger creatures than ever before.

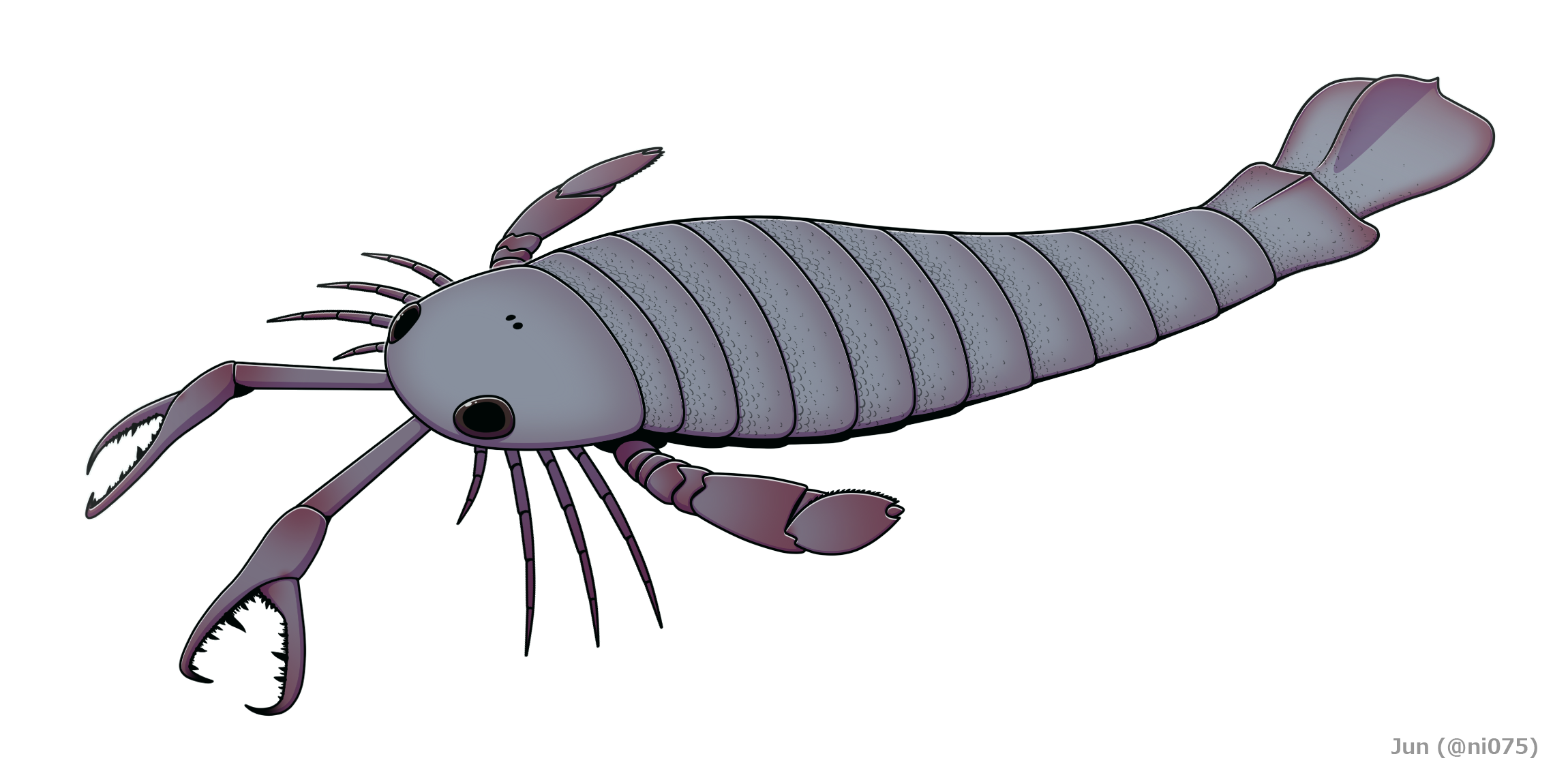

Predatory armored marine life, known as Eurypterids, reigned supreme. The largest of which, Jaekelopterus, grew to more than eight feet in length. Remaining mostly near the sea floor, using their long jointed arms and jagged claws to hunt, these massive vertebrates had no natural predators. The constant eating and moulting of their shells, coupled with the evolution of a lighter exoskeleton, led to an extreme level of gigantism.

Rendering of Jaekelopterus (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Despite the dominance of the Eurypterids, not every major predator in the Devonian was of the crustacean variety. Dunkleosteus was an early species of fish, notable for its massive size and armored jaws. These jaws not only allowed for massive bite strength (like modern sharks) but a remarkably quick bite time, snapping shut on prey within 60 milliseconds. This enabled Dunkleosteus to hunt the abundant armored species, like Jaeklopterus’s smaller relatives.

The Devonian period was brought to a slow end. While the exact cause is a subject of constant research, the massive decline in species is theorized to have arisen from several coinciding sources.

The expansion of floral life was not favorable to the fauna, as oxygen and carbon levels were disrupted to such an extent that the smaller species couldn’t find enough food, causing a lack of prey for top predators. In addition to the expanding plant life, underwater sediment was disturbed by massive earthquakes, volcanoes, and continental drift. This activity released elements and minerals that changed water chemistry within highly populated environments. The changes killed off an estimated 75 percent of species alive at the time.

‘The Great Dying’: 358 — 252 million years ago

Although life on Earth was devastated by the Late Devonian Extinction, it would rebound to diversify on a new level. The following two eras are known as the Carboniferous and Permian, with creatures moving out of the oceans to evolve into new arthropods like insects and the first reptiles.

Of these newly land-dwelling reptiles, few are as striking as Dimetrodons, with their low stature and massive spinal fins. These animals could grow to 13 feet long, and the fin is theorized to have been used for courtship or for regulating body temperature. This would have kept the cold-blooded reptiles from becoming sluggish while they exercised their power as apex predators, hunting fish in the shallows and smaller land reptiles.

Dimetrodon (Credit: Creative Commons)

Not only were land reptiles growing in size, but the insects appearing in prehistoric jungles were of impressive measure. Massive ancestors of modern dragonflies, called Meganeura, were plentiful, ruling the skies in the absence of flying reptiles or birds. Meganeura were not only gigantic, with wingspans over 2 feet, but carnivorous, using jagged mandibles to ensnare prey. (If you encountered one of these on a hike through the Permian era, bug spray wouldn’t quite cut it.)

The Permian-Triassic extinction that would follow was so extreme that historians refer to it informally as “The Great Dying.” The Great Dying is theorized to have been driven by geological upheavals like the Siberian Traps. These massive northern volcanic eruptions released abundant carbon dioxide and raised temperatures planet-wide, and changed air and water composition. This increase in CO2 also led to a decrease in oxygen, which had deadly effects for most land animals. Approximately 90 percent of all species were wiped off the face of the planet.

Triassic-Jurassic Extinction: 252 — 200 million years ago

The Great Dying decimated most land-dwelling life, but some reptiles survived. These creatures would spread and diversify, becoming not dinosaurs but their precursors: archosaurs. These archosaurs are largely gone today but survive in the form of crocodiles.

Abundant vegetation gave rise to massive herbivores, notably a monophyletic group known as Sauropods, the largest land animals to ever exist and good examples of why you should always finish your vegetables. They were surely an impressive sight, striding through the prehistoric jungles, using their long necks to eat easily from the canopies of the aptly named Giant Sequoias.

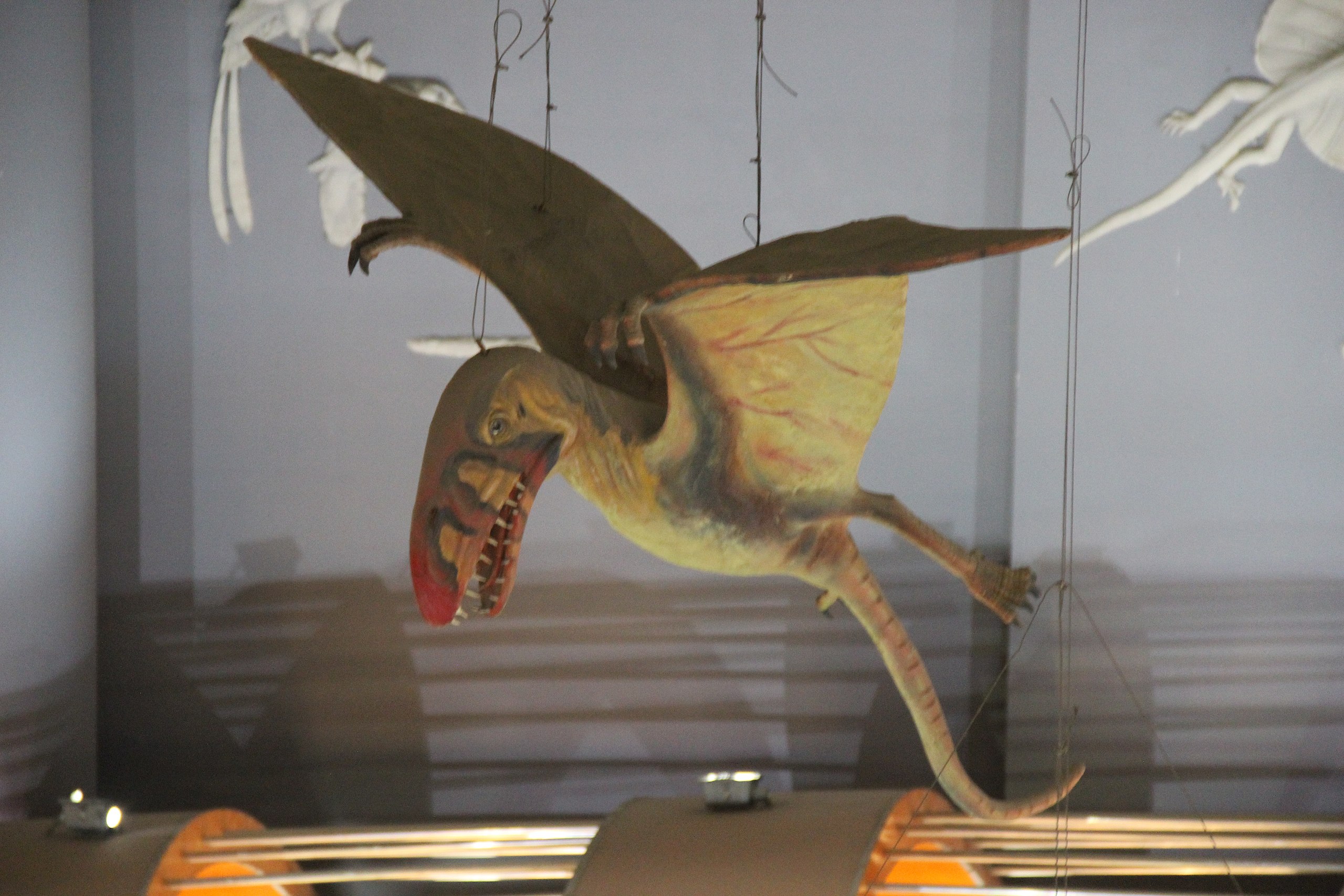

The Triassic is also when reptiles took to the skies. Pterosaurs were the first vertebrates to develop flight, with the largest having wingspans comparable to small planes. They generally evolved long necks and mighty beaks, capable of swallowing their prey whole.

A lifesize model of the pterosaur called Dimorphodon. Henan Geological Museum, China (Credit: Gary Todd, via Wikimedia Commons)

Like the Great Dying and Devonian extinctions, the Jurassic came to an end because of temperature and chemistry differences. Carbon dioxide was released in massive lava flows, big enough to cover the continental U.S. in a quarter-mile layer of magma. This warmed the Earth between five and eleven degrees Fahrenheit and acidified the oceans. Unable to catch a break that would last much more than 100 million years, life was set back once again, losing 80 percent of species at the time. However, many plants, mammals, and early dinosaurs were untouched.

Chicxulub Event: 200 — 66 Million Years Ago

The remarkable reptile growth of the previous 50 million years set the stage for even bigger things to come in the Jurassic period. A much warmer planet and rebounding reptile life would combine to give rise to the most well known of ancient animals: dinosaurs.

Many of the most dominant species of dinosaurs are also the most recognizable. Tyrannosaurus Rex, with its massive jaws offsetting its powerless arms. The horned Triceratops, an herbivore with the power to contend with most predators. And the distinctive Ankylosaurus, covered by armored plates and wielding a club-like tail.

Massive reptiles not only roamed the land but swam in the seas. With the largest discovered fossil measuring 49 feet, Liopleurodon was an apex predator in its environment. Some paleontologists even theorize that it would hunt dinosaurs drinking at the water’s edge, bursting out of the water to drag them into the depths – a rude but effective hunting tactic.

Artist’s depiction of a Liopleurodon (Credit: DiBgd, via Wikimedia Commons)

The most recent mass extinction is also the most well-known: the meteor that killed the dinosaurs. That cataclysm is known as the Chicxulub event, after the area of the Gulf of Mexico where the six-mile-wide meteor impacted. The collision was so massive it threw up millions of tons of dust and sediment into the atmosphere, which clouded the skies for months or even years, leading to massive temperature drops and the destruction of most of the ecosystems created up to that point.

In recovering from the disaster, a new form of dominant life emerged. One species of the warm-blooded mammals that survived the temperature drop evolved over the next 65 million years, eventually walking upright, using tools, forming civilizations, and writing blogs about themselves.

The Holocene Extinction

Even by Darwin’s lifetime, in the mid-1800s, there were plenty of examples of human-caused extinctions, largely as a result of demand for food. The iconically goofy Dodo, wiped out in 1681 to feed Portuguese sailors and their settlements. Eurasian Aurochs, massively imposing ancestors of modern cows, prized for their meat and gone by the 16th century. And who could forget the legendary Woolly Mammoth, whose towering strength was no match for prehistoric hunters in the reaches of Northern Siberia.

These examples of animals wiped out before the industrial era only serve as evidence that humanity’s insatiable appetites are nothing new, but the real problem is the destruction of habitats. Even before humans realized the effects of greenhouse gasses on the planet at large, life had been contending with large-scale disruption as a result of these gasses for billions of years.

Despite how precarious the situation of modern plant and animal life is, we can find a small amount of comfort. The march of evolution is far from over. As long as Earth is intact, life will continue through natural and unnatural devastation. If you lose hope, think of the once-mighty dinosaurs. Many died, yes, but they also changed – evolving feathers, dropping size, and gradually transforming into the lovable birds we hear chirping in the trees.

Ω

Wallace Burgess is a Contributing Writer for MagellanTV. He is a recent graduate of Syracuse University (go Orange!) where he earned Bachelor of Arts degrees in both Writing and Rhetoric, and Sociology. He lives in New York City and enjoys playing poker and video games.

Title Image Credit: Musee Cantonal de Geologie, Lausanne/Roman Deckert/Wikimedia Commons