The horrifying flashfire that took the lives of three American astronauts in January 1967 shocked the world. It didn’t have to happen.

◊

There has been a lot written and discussed about the Apollo space program. Numerous books, television programs, and feature films have kept alive the amazing story of humans’ first journeys to the Moon. But Project Apollo, as NASA called it, wasn’t without tragic losses. The generation that watched this epic story unfold in real time on black-and-white television remembers well the catastrophe that befell the first Apollo mission before it even left the ground – the fire in the command module during a launch rehearsal, killing three brave astronauts.

Would the Apollo program have succeeded without the disaster? Would astronaut Gus Grissom have eventually walked on the Moon? Who knows? But most agree that the fire was a pivotal moment for the American space program. In fact, many would argue that the resulting changes to the program and the re-evaluation of the spacecraft design led directly to the successful Moon landings.

Let’s take a closer look at the story of Apollo 1 – and how NASA was able to overcome the tragedy and successfully – and safely – transport astronauts to Earth’s enticing satellite.

Check out the MagellanTV original documentary The Incredible Journey of Apollo 12.

Project Apollo Had an Ominous Link to a Greek Myth

The American program to land men on the Moon was named Apollo by NASA engineer and manager Abraham Silverstein in 1960. The ancient Greek god Apollo was an apt namesake for the project, as he was a multitalented god of many things: god of the Sun, light, prophecy, philosophy, archery, truth, poetry, music, manly beauty, and medicine, to name just a few. And NASA was going to need experts in a broad array of fields to make good on President John F. Kennedy’s vow to land American astronauts on the Moon before the end of the 1960s. Winning the Space Race as part of the ideological Cold War with the Soviet Union became a primary goal of the United States.

Although Silverstein probably didn’t think of it, there was another Greek myth involving Apollo that could have been taken as an ominous sign. Apollo had a particularly active role in accounts of the Trojan wars. For example, he was said to have guided the arrow shot by Paris that pierced the vulnerable heel of Achilles.

He also had a rather passionate desire for a Trojan princess, Cassandra, whom he gifted with prophetic visions in return for her love. When she reneged on her promise of a relationship, he retaliated with a curse: Her visions, although true, would not be believed by anyone; and when she foresaw the defeat of Troy, her warnings fell on deaf ears.

Which brings us back to the 1960s, when there were plenty of “Cassandras” warning that Project Apollo was rife with serious issues that urgently needed to be addressed – but no one was listening.

The Ill-Starred Crew of Apollo 1

At the 1966 press conference announcing the Apollo 1 crew, the mission commander was asked if their flight were to be a lunar mission, who would go down in the Lunar Module to the surface of the Moon. The astronaut responded with a smirk: “If it was this crew, it would be me and somebody else.” He drew a hearty laugh from the gathered audience.

That was the dry humor of space-mission veteran, engineer, and U.S. Air Force Lt. Colonel Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom. And, if events had turned out differently, he most likely would have walked on the Moon.

In 1961, Grissom had flown the second sub-orbital Mercury program flight and survived by the skin of his teeth after static electricity build-up prematurely triggered explosive bolts on the capsule’s hatch. He almost drowned and the capsule sank; it was retrieved from the ocean depths some 35 years later. Grissom went on to command Gemini 3, in 1965, the first manned mission of the three-step space program. He had developed a no-nonsense reputation as a determined astronaut and engineer, and was a natural to be named commander of Apollo 1.

The U.S. manned space program progressed through three distinct stages: Mercury, the first set of flights carrying solo astronauts; Gemini, with two astronauts per orbital mission; and Apollo, which carried three crew and eventually landed the first men on the Moon.

The senior pilot for the mission was fellow USAF Lt. Colonel Edward H. White, whose public claim to fame was having been the first American to walk in space on the Gemini 4 mission. Ed was strong, fit, and experienced, and if you wanted someone in your corner when the chips were down, you’d choose Ed White.

The third crewman and pilot was U.S. Navy Lt. Commander Roger B. Chaffee, a space rookie, one of the new astronaut intakes. He had the “smarts” and was integral to managing the new and very complex Apollo space capsule.

Apollo 1 astronauts Ed White, Gus Grissom, and Roger Chaffee (Credit: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Apollo Contract Goes to North American Aviation

Apollo 1 was to be a “shakedown” mission, in which the newly designed capsule and all of its systems would be tested in orbit around the Earth. The Apollo capsule was by far more complex and technically challenging than the previous Mercury and Gemini capsules, which had been produced by McDonnell Aircraft. The idea was to find and fix the inevitable bugs in the design before a mission was launched to the Moon itself.

To the surprise of some – and the dismay of others – North American Aviation was awarded the lucrative contract to build the Apollo command capsule and service module. Many suspected influence-peddling or good old-fashioned political pork-barrelling in Washington, DC, to be involved.

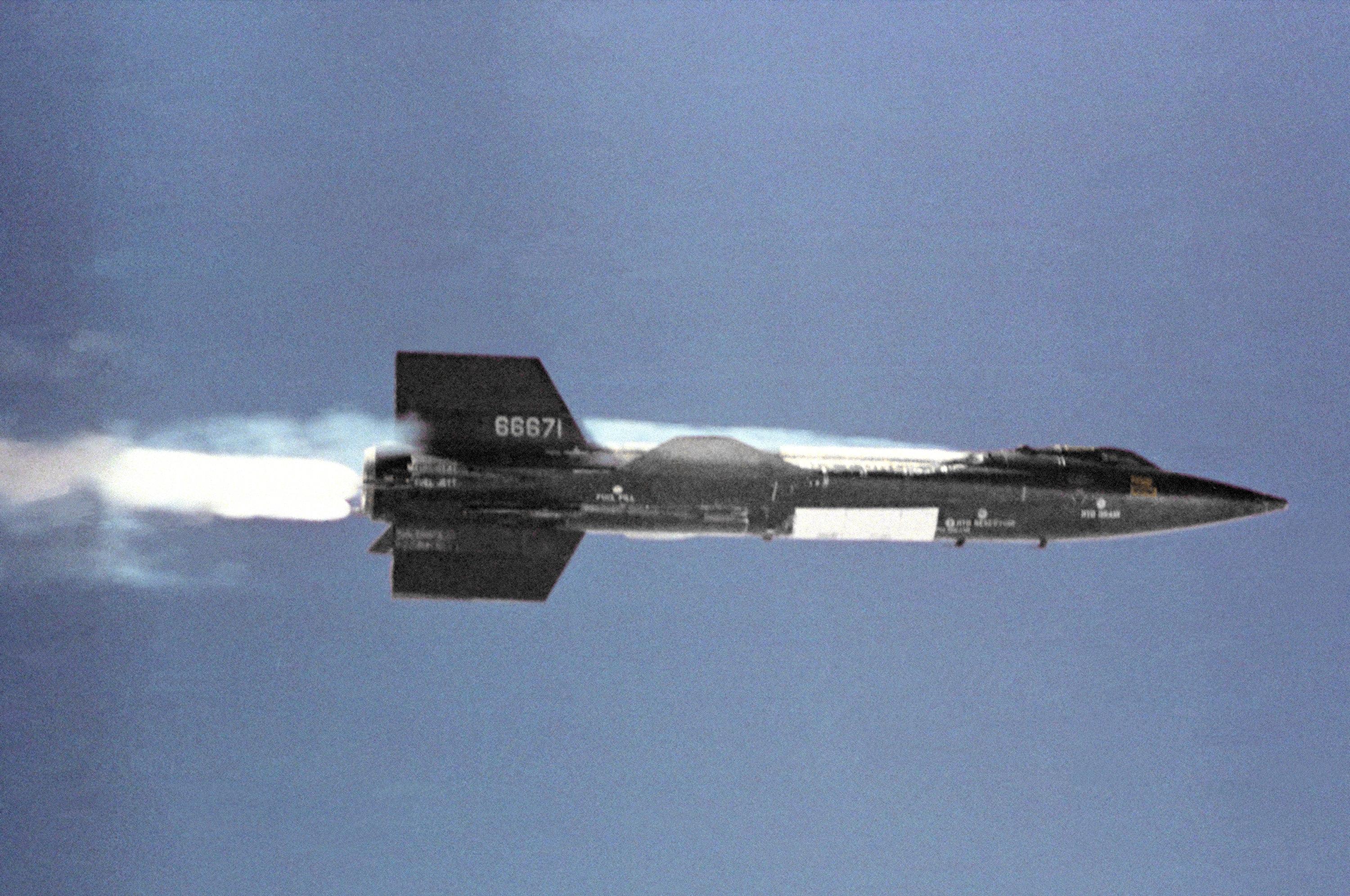

North American made its name building warplanes like the B-25 bomber during World War II and the superb F-86 jet fighter during the Korean War, but it had no experience with capsules for space flight. Its nearest relevant project was the X-15, a small rocket-propelled aircraft that flew to the edge of space at a speed of more than 4,000 miles per hour – impressive, to be sure, but a far cry from producing spacecraft to carry astronauts to the Moon.

X-15 in flight (Credit: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons)

Right from the start, at the very early stages of development, North American had difficulties in fulfilling the contract. Cost overruns, manufacturing delays, missed key performance indicators, and managerial issues became a major concern. For the crew of Apollo 1, it was all smiles and handshakes in front of the camera, but behind the scenes it was a different story.

Concerns Are Raised

Gus Grissom was particularly vocal about the spacecraft’s shortcomings in both design and workmanship. He complained to the engineers, fellow astronauts, and management. He didn’t mince his words and labeled the spacecraft a “lemon.”

Engineers at NASA and North American itself were also concerned about the project. In late 1965, NASA became so concerned with the operations at the company that George E. Mueller, head of the Office of Manned Space Flight, sent his right-hand man, General Samuel C. Phillips, to North American’s facility in Downey, California, to take a look. He returned with a scathing report on the company and its manufacturing process.

Left to right: Robert Seamans, James Webb, George Mueller and Samuel Phillips testifying before the U.S. Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Services, May 9, 1967 (Credit: NASA on The Commons, via Wikimedia Commons)

Mueller and Phillips made direct recommendations to North American senior management to improve the situation or else. But even with managerial changes and improved oversight, progress was still under par. Technical problems continued, along with faulty communications and wiring, and the environmental control system (ECS) leaked flammable glycol coolant. In fact, engineers had the ECS unit removed and replaced several times.

A North American quality control and safety inspector, Thomas Baron, compiled a long list of issues but his reports to management went unanswered. In 1966, Baron went over the heads of North American and supplied a 55-page report to NASA on irregularities in manufacturing and fitting out the Apollo capsule. Items in his report included shoddy workmanship, the use of non-certified materials such as certain adhesives, and substandard wiring.

The Baron Report had merit, and NASA took the matter up directly with North American. However, Baron was unhappy with the response from both the space agency and the company, so he leaked his report to the public and was fired in late 1966.

The List of Issues Grows Alarmingly

The list of problems with the capsule grew as the launch deadline neared. Major issues were left unaddressed: Despite the presence of flammable materials in the capsule, no thought had been given to fire suppression, compartmentalizing for fire control, or any fire-fighting equipment. In addition, communication equipment was beset with issues; the ECS continued to leak flammable glycol into the cabin; and the wiring looms were often left exposed, some even frayed.

The capsule’s hatch-system was another point of contention, as the Block 1 design was not intended to be opened in flight. It consisted of three hatches. The first was the air-tight internal element that had to be lifted into place and secured from the inside by the astronauts. The outer hatch was then bolted in place by ground crew, which took several minutes with a torque wrench. Finally, there was the third element – the shroud hatch, which was part of the capsule’s outer protective cover during the boost phase of flight.

Apollo 1 hatch on display at Kennedy Space Center (Credit: Iraq vet, via Wikimedia Commons)

The last and potentially most problematic element in the capsule itself was the internal atmosphere: pure oxygen. In space, the cabin would be pressurized at 5psi. However, at sea level, the cabin pressure was set to 16psi, 1.3 psi greater than outside the capsule, which allowed it to be checked for leaks.

And then there were the astronauts’ spacesuits. They were essentially hand-me-downs from the Gemini program. The G3C suit with a few minor modifications became the A1C suit. With an outer layer of nylon, they had been designed with the Gemini escape system in mind, not the Apollo system. Worse, they were flame rated for just five seconds and not at all fireproof.

Everyone was aware of these shortcomings, but the rapid pace of the program seemed to overtake the need to rectify the issues.

Catastrophe Strikes Apollo 1 on the Launch Pad

Despite the many unaddressed, predictable problems, in late January 1967 the Apollo 1 mission was on schedule for a February launch, and final training and testing was underway. The command capsule and service module were mated to the top of the Saturn 1B rocket on the launch pad.

One of the final tests was the ‘Plugs out’ test on the launchpad, to test all the systems under pre-launch conditions. “Plugs out” meant the capsule would be sealed, running on its own internal power, and utilizing radio communications and telemetry. It was considered a “safe” operational test, as the Saturn rocket was not fuelled and the craft’s pyrotechnic systems were disabled.

For the test, the crew was sealed in with the cumbersome hatches, and the cabin was then pressurized with pure oxygen. The astronauts then spent hours going through checklists and performing pre-flight activities, frequently pausing for issues that arose – including an odd smell in their suit air supply. Frustrations built up due to faulty communications systems connecting the capsule and the two checkout buildings, drawing a sarcastic comment from Gus Grissom: “How are we going to get to the Moon if we can’t talk between two or three buildings?”

Moments later there was a voltage anomaly in one of the main bus circuits. Somewhere in the miles of electrical wiring there was a short – an arc of electricity triggering an intense flashfire, which was fueled by the pure oxygen atmosphere and flammable materials that had been soaked in that very oxygen. Investigators later estimated that the temperature in the cabin peaked at 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit. The pressure in the cabin grew so high that it ruptured the capsule’s pressure hull, flames leaping out of the cabin into the white room surrounding the capsule.

Gus Grissom was closest to the source of the fire, and his suit was quickly penetrated by the flames. All three space suits on the single oxygen loop were flooded with high-pressure toxic fumes from the fire, suffocating the crew in seconds.

The charred remains of the Apollo 1 capsule (Credit: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Investigation into the Apollo 1 Disaster

The deaths of Grissom, White, and Chaffee were a terrible shock to all at NASA and, indeed, to everyone who had been following Project Apollo’s progress with such excitement and optimism. That the disaster occurred during a ground test only added to the distress. How could this have happened? Who was to blame?

The entire Moon program was in jeopardy, both technically and politically. The Apollo program was halted, and an investigation by the Apollo 204 Review Board was initiated. The nine-member review board was chaired by NASA’s Langley Research Center director, Floyd L. Thompson. Working with great urgency, the board issued its report on April 5, 1967.

The report noted myriad issues with the Apollo spacecraft. Among its key findings were:

- There had been deficiencies in the command module design, including in its design, manufacture, installation, rework, and quality control of the electrical wiring.

- The environmental control system had a history of removals and technical difficulties. The design of the ECS unit made removal or repair difficult. Coolant leakage at solder joints had been a chronic problem, and the coolant was both corrosive and combustible.

- No vibration test had been made of a complete flight-configured spacecraft. Spacecraft design and operating procedures had required the disconnecting of electrical connections while powered. No design features for fire protection had been incorporated.

Congressional hearings were held, and, predictably, a political blame game ensued. Some in government wanted to shut down the space program altogether. Astronauts, management, and engineers testified before Congress; among them was whistleblower Thomas Baron, who had been fired by North American when he attempted to shine a light on the Apollo spacecraft’s problems. (As fate would have it, Baron and his family died a week after his testimony when their car collided with a locomotive.)

A Safer Project Apollo Rises from the Ashes

NASA management took a severe thrashing but survived. North American Aviation’s responsibility ultimately led to its merger with Rockwell-Standard to become North American Rockwell. The newly formed company continued its contractual obligations and produced the hardware for all 11 Apollo missions.

All the investigative, administrative, and political activity resulted in serious changes to the engineering, manufacture, and safety of Apollo spacecraft. Among the changes:

- Apollo’s Block 1 capsule design was abandoned and replaced by a Block 2 version with over 1,000 corrections hurried into production.

- New fireproof beta-cloth spacesuits were developed.

- The number of flammable items in the cabin was reduced.

- Reworked wiring looms under protective covers and new leak proof plumbing joints were installed.

- A new single-hatch design that could be opened in seconds by the crew was developed, and rapid escape procedures for the crew were instituted.

- A new cabin atmosphere protocol was developed, allowing ambient air to be used at launch and then purged from the cabin during ascent to be replaced with 5 psi of pure oxygen.

Apollo 1 memorial ceremony, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, January 27, 2015 (Source: The Center of the Aerospace Testing Universe, Edwards Air Force Base)

With remarkable and concerted effort, NASA was able to get the Moon program back on track. Apollo 7, the first manned Apollo flight, lifted off in October 1968, completing the mission designed for Apollo 1. Less than a year later, on July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 landed two astronauts on the Moon, fulfilling President Kennedy’s historic vow to get it done before the end of the 1960s.

Ω

Living in Melbourne, Australia, Andrew Thomson is a television production specialist with 45+ years experience in the broadcast and streaming industry. He has run his own production company, Astro Media, since 2004, producing original documentary programs for the international market.

Title image: Apollo1 crew, left to right, Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee (Credit: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons)