Fungi form a web under our feet that we often do not see, but it might have the potential to revolutionize the world around us. They could heal our most confusing diseases and could solve our most confounding ecological issues. “Magic mushrooms” could also help heal illnesses like depression and anxiety, and certain fungi can even break down plastics and help land regenerate after nuclear disasters. So why haven’t we tapped into their powers yet?

◊

They’re below our feet, in the air we breathe, in what we eat and drink, in our clothing, and in our medicine. Some of them can kill us, while others can make us see strange, dreamlike visions. They can survive on the outsides of rocket ships and can eat through titanium quartz. Some people think these invisible warriors have the potential to save the world.

They’re fungi, a kingdom of species that is as bizarre as it is magical.

"If it weren't for fungi, we wouldn't be here." (Credit: Dandip Katel, via Wikimedia Commons)

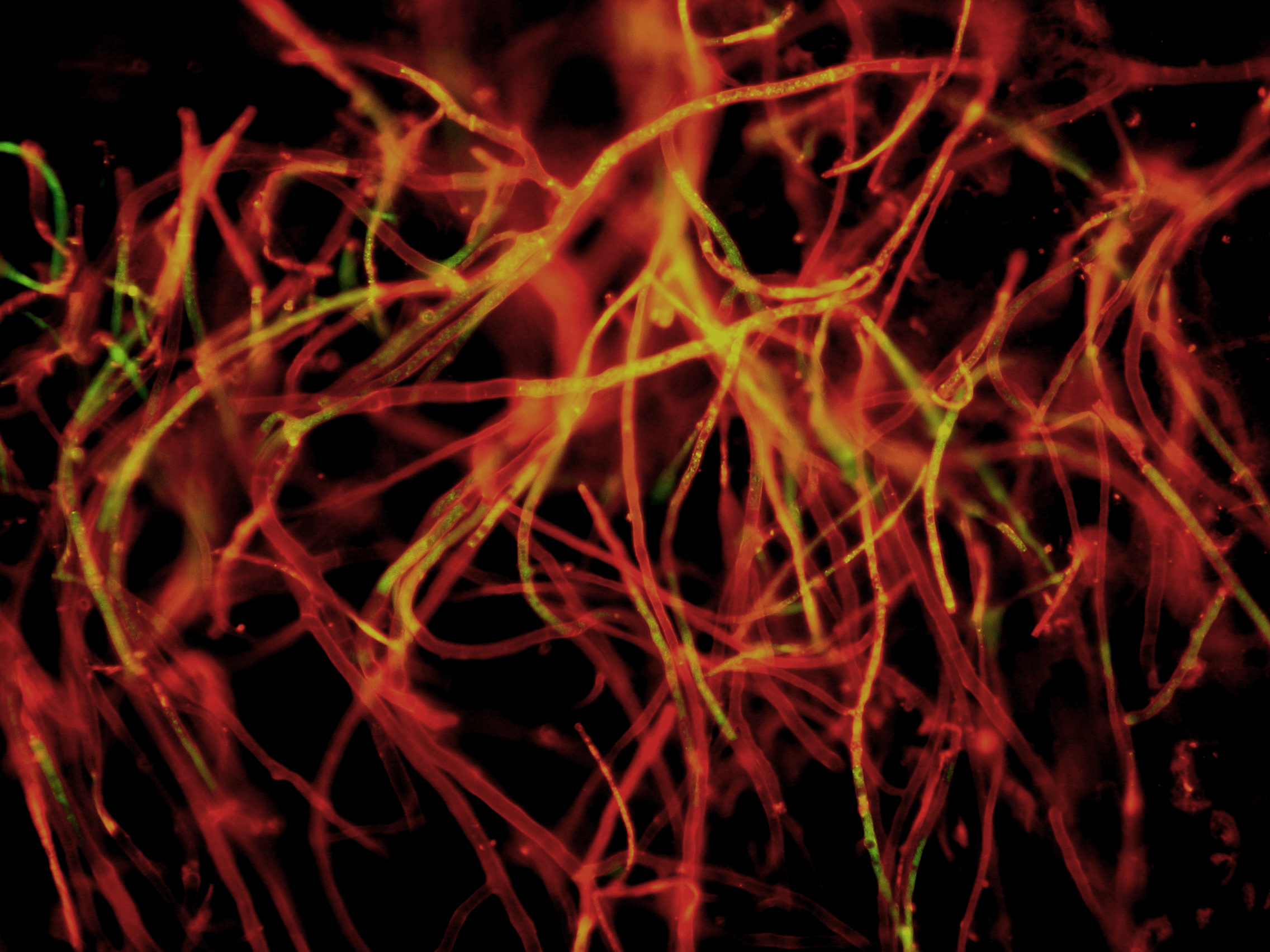

Fungi exist in fibrous, lattice-like webs called “mycelium,” which often connect entire forests and pass messages across vast distances using chemical signals. These mycelium webs are all around, yet most of us hardly ever notice them, though in the words of Paul Stamets, one of the world’s leading mycologists, fungi can “save our lives, restore our ecosystems and transform other worlds.”

How, you ask? Could a mushroom really be a door to life’s mysteries? We’ll have to start by looking down at the worlds beneath our feet.

What Are Fungi?

A fungus is any member of the kingdom of fungi (which is separate from the kingdoms of plants and animals). There are about 144,000 known species of fungi, ranging from mushrooms to puffballs to slime molds. (A 2011 study proposed that there might actually be a total of around 5.1 million species.) Unlike plants, fungi cannot perform photosynthesis, so they ingest their energy like humans: by digesting organic substances. In fact, fungi split from animal eukaryotes about 9 million years after plants did, meaning that we’re more closely related to them than we are to the plant kingdom.

Some fungi are single-celled organisms, like yeast, but multicellular fungi (such as mushrooms) are composed of tangles of cells that resemble branches of trees. Each tangle is called a “hyphae,” and when a bunch of hyphae band together, this forms the aforementioned mycelium.

"Without this fungal web my tree would not exist. Without similar fungal webs no plant would exist anywhere. All life on land, including my own, depended on these networks. I tugged lightly on my root and felt the ground move." —Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures

Though they’re made up of tiny parts, mycelium are some of the largest living organisms in the world. Oregon’s 3.5 mile-long honey fungus stretches across the Blue Mountains; it is also probably around 2,400 years old. Invisible and yet resilient, the honey fungus – which can survive on dead organisms as well as living ones – might just survive climate change, even if the natural landscape around it dies.

Mycelium (Credit: Christian Scheckhuber, via Wikimedia Commons)

Yet judging by fungi’s ability to treat ailments of all kinds, the honey fungus isn’t trying to be the last living organism on Earth. Instead, fungi might be trying to keep us all alive.

The Healing Powers of Fungi

In 1928, the bacteriologist Alexander Fleming discovered a mold called Penicillium notatum. By the 1940s, scientists had converted the Penicillium fungi into the first mass-produced antibiotic. Some scientists warn that due to chronic overuse, we may be developing resistance to penicillin’s antibacterial properties, but they also believe that the key to our next major antibacterial vaccine lies in the Penicillium fungi. So essentially this bacteria-devouring fungus is a gift that simply keeps on giving.

Bioluminescent mushroom (Omphalotus subilludens) (Credit: Alexey Sergeev, via Wikimedia Commons)

And it’s not alone. Fungi have often given us incredibly powerful medicines. The fungi commonly known as ergot (also a primary source of the psychedelic drug lysergic acid diethylamide) is capable of inducing labor and controlling hemorrhage after birth. Fungi have also given us the drug cyclosporine, which helps prevent transplant rejection. It was vitally important in the discovery that genes control the expression of enzymes, a revelation that won the scientists George Beadle and Edward Tatum the Nobel Prize in 1958.

Fungi helps us heal physically, and for thousands of years, they’ve helped people heal and grow mentally, too – perhaps even contributing to the development of human consciousness itself. Ancient cultures believed in vision quests, divine mushrooms, and psilocybin trips that could provide windows into the world of the gods.

The healing effects of psilocybin have been well-documented, albeit distorted by some proponents. Unfortunately, a crackdown on recreational drug use beginning in the late 1960s prevented psilocybin from being rigorously studied by mainstream medicine, but recently there’s been renewed interest in the drug. Modern medical researchers have been studying psilocybin (the active psychoactive component of so-called “magic mushrooms”) for its potential to help combat some of our trickiest and most devastating diseases.

"Magic Mushroom" (Gymnopilus purpuratus) (Credit: Mycellenz, via Wikimedia Commons)

Over the past several decades, psilocybin has been used successfully as a treatment for OCD, depression, and PTSD, among other ailments. In particular, it appears to show great potential in the treatment of patients suffering from major depression. It seems that psilocybin can help people with almost incurable depression more effectively than other medications. In November 2019, the FDA designated psilocybin as a “breakthrough therapy,” which means its medical use is expected to explode in popularity over the coming years.

“When we look within ourselves with psilocybin, we discover that we do not have to look outward toward the futile promise of life that circles distant stars in order to still our cosmic loneliness. We should look within; the paths of the heart lead to nearby universes full of life and affection for humanity.” —Terrence McKenna, True Hallucinations

Now, this isn’t meant to advocate for recreational drug use. But under the proper circumstances, and if taken with care, “magic mushrooms” can be powerful and healing, even when not taken in an explicitly medicinal context. Psilocybin can, supposedly, increase humans’ feelings of connection and kinship with life and nature, sometimes leading people to develop a sense of responsibility to the planet.

In our world of anxiety, missed connections, and isolation from each other and nature, fungi might be what we need – in more ways than one. Knocking out existential dread, waking us up to climate change, and modeling compassion and mutuality? It sure sounds like fungi might have the answers many of us have been looking for.

Fungi: An Ecological Powerhouse

We’re in the middle of an ecological catastrophe on Earth. Climate change is causing more and more disastrous floods, storms, and fires, and many of our ways of life are clearly unsustainable.

While no one solution will help fix the climate problem, fungi (that fabulous kingdom of life!) could potentially play a major role in addressing some of the worst consequences of environmental degradation. Among its many properties: Fungi contain rich stores of minerals and require very little energy to grow, so they could also present a great alternative to the environmentally devastating process of livestock farming and factory farms. Mushrooms can increase garden and soil health, reviving ecosystems and improving sustainability.

“If fungi already function as sensors, processing and transmitting information through their networks, then what could they potentially tell (or warn) us about the state of our ecosystem, were we able to interpret their signals?” —Hua Hsu, “The Secret Lives of Fungi,” The New Yorker

Fungi are experts at destruction and transformation. Some species of mycelium are capable of digesting toxins like PCBs and petrochemicals, and converting these poisons into healthy energy. Mycelium can also break down plastic, converting one of our most dangerous and poisonous substances into something that can even be eaten by humans. The fungus Pestalotiopsis microspora is capable of surviving entirely on polyurethane (the main ingredient in plastic), and can even break plastics down into new, safe fungal tissues.

So fungi can convert toxins and plastics into fertile soil. Fungi are capable of taking our worst creations and turning them into something good. The moldy spores that grow on piles of agricultural waste, or on cardboard and carton-filled dumps, can generate a material that inventors around the world are now using to build compostable packing materials, vegan goods, home equipment, and more. That’s nothing less than magic, isn’t it?

Regenerative Culture: Paul Stamets’s Visions of Radioactive Healing

All these miraculous possibilities are part of a field called “mycoremediation,” which is becoming a popular way to restore ecologically devastated landscapes.

It’s hard to discuss this field (or to mention anything about fungi’s powers) without mentioning Paul Stamets, a mycologist who has spent decades studying fungi’s regenerative qualities. As a teenager, Stamets was able to cure his stutter during a magic mushroom-induced trip, and his fascination began. Today, his TED talk, “6 Ways Mushrooms Could Save the World,” has been viewed over 10 million times, and Stamets has played a major role in bringing fungi’s magic to the mainstream.

He’s conducted tons of experiments, including many that explored fungi’s abilities to convert ruined landscapes into lush, livable ecosystems. Currently Stamets is looking into planting fungi at the sites of chemical leaks, forest fires, and nuclear catastrophes.

Fungi has a way of appearing on the sites of such disasters. After the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, for example, the very first vegetation to sprout was a matsutake mushroom. After the disaster at Chernobyl, fungi also leapt into action, growing out of radioactive waste and on reactor walls, converting poison into new life.

“We are stuck with the problem of living despite economic and ecological ruination,” writes Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing in The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. “Neither tales of progress nor of ruin tell us how to think about collaborative survival. It is time to pay attention to mushroom picking. Not that this will save us – but it might open our imaginations.”

When you look at fungi’s ability to grow in the midst of an apocalyptic scenario, or when you examine the interconnectedness of a mycelium network, it’s easy to see why Stamets and many others see deep, even spiritual significance in fungi.

Digging Deeper: Fungi, the Internet, and Beyond

Fungi are often described as “nature’s Internet” due to mycelium’s uncanny resemblance to early prototypes of the World Wide Web. We know that some fungi even “hack” other fungal networks to stay alive. But mostly, these networks exist in a constant state of mutual aid, rushing signals and nutrition to each other as needed, passing messages through trees as easily as we volley text messages off into the distance.

“What’s the haunting phrase I’ve heard used to describe the realm of fungi? The kingdom of the gray. It speaks of fungi’s utter otherness – the challenges they issue to our usual models of time, space, and species.” —Robert McFarlane, “The Understory,” Emergence Magazine

Fungi’s magical interconnectedness has even inspired a field called “radical mycology,” which explores the ways fungi can expand humans’ horizons. Founded by Paul McCoy, a conference called the Annual Radical Mycology Convergence now draws hundreds of people each year. Activists, scientists, and psychonauts join together to explore fungi’s secrets, asking questions like: What can fungi teach us about our own brains? Could they shed new light on our relationships with each other?

Most come to similar conclusions. Fungi – and mycelium, specifically – are a sign that even if we can’t see it, all living things – including us – are parts of a great interconnected web of life, whether you see it as a global brain or a giant forest, an Internet or a tangle of vibration and waves.

This idea is not a new revelation. Many Indigenous peoples have always described the forest as a living entity of which we are just a small part. Now more than ever, it’s clearly time to listen to these old stories. And of course, it’s time to listen to the fungi.

Ω

Title image: Edible Mushroom in Basket by George Chernilevsky via Wikimedia Commons.