Bridges of all shapes and sizes have been connecting communities for millenia. They’ve also been known to tear us apart.

◊

Few innovations have changed the world as fundamentally as bridges. With an impact on par with humans’ harnessing of round objects as wheels or the creation of sea-worthy vessels, bridges have facilitated travel through parts of the world that don’t geographically align.

Humanity puts a lot of pressure on bridges – physically and metaphorically. There are millions of bridges all over the world. Billions of people cross over them every day, but with radios blaring or podcasts playing, many of us might not even notice how often we traverse them. Connecting communities has been appropriated as a cliché catchline for countless marketing campaigns, but the reality is that not all bridges receive a warm welcome.

Conflicts over the communities connected by bridges, the traffic they redirect, and who owns bridges have plagued countless elevated pathways for millennia. Beyond that, images of snapped cables, suicide nets, and collapsed structures can circulate worldwide within a matter of seconds in the modern world – reminding us of the precariousness of the roads we travel and what’s beneath them.

See how a spectacular bridge in the South of France has overcome the challenges of nature to connect people and places in MagellanTV's Millau Viaduct: The Bridge in the Sky.

The Evolution of Bridges

The bridge is a natural phenomenon that long predates humanity’s creation of them with stone and steel. For example, ant colonies have evolved to create “living bridges.” Researchers from Princeton University and the New Jersey Institute of Technology conducted experiments to understand the impetus behind a group of ants’ decision to form a suspended path with their bodies, rather than finding an alternative route. While no single ant has the length or strength to bridge a divide, when dozens of them work together, they can form a solid structure in a matter of seconds.

Ants creating a bridge out of their bodies (Credit: Igor Chuxlancev, via Wikimedia Commons)

Granted, human beings don’t form living bridges, and few communities today seem to want to project an image of themselves being a part of a “hive mind.” The closest any of us may get is being a part of a human net catching another human being during a trust-fall exercise. The general human inclination toward individualism may not make us wish to morph into temporary living structures in our landscape, but it has enabled great thinkers to move the needle on what we could build – not with our bodies but with the tools we’ve created.

Stone Dominates Early Bridge Designs

Bridges have come a long way since the early days when stacks of stones were used to span creeks and streams. Many of humanity’s earliest bridges have fallen into disrepair, become casualties of war, or been modernized to accommodate changing traffic patterns and weight loads. The very earliest bridges were made of wood logs laid across a gap. Sometimes they were accompanied by vine ropes to facilitate crossing, but over time our ancestors moved on from the thin, easily degradable designs.

The Arkadiko Bridge in Greece is one of the oldest bridges still in existence. It has survived more than three millennia since its supposed creation around 1300 BCE. At about that time, clapper bridges were created by layering long, thin stones on a series of pillars across a body of water or valley. As an easily replicable and affordable bridge type, these were still being built as late as the 19th century.

Arkadiko (or Kazarma) bridge, Argolis, Peloponnesos, Greece (Credit: Zde, via Wikimedia Commons)

Stone has historically been one of the most common building materials for bridges, but its potential far exceeds the rudimentary designs of early clapper bridges. That can be seen in the southern Hebei province of China, where The Great Stone Bridge was constructed. Still standing today, it is the world’s oldest open-spandrel arch bridge, predating open-spandrel European bridges by over 1,000 years. This bridge deviated from the more common style of cantilever bridges that were used throughout Asia at the time. These bridges used heavy weights to prevent bridges from collapsing.

Arches and New Materials Permit Greater Complexity

About 700 years after the Arkadiko Bridge was built, the Mesopotamians started manufacturing bricks specifically for use in arch bridges and aqueducts. Later, the Romans led the way in bridge engineering in ancient Europe.

The Romans are renowned for their enduring architecture, and much of that can be credited to their use of arches, which made it possible to create longer, more structurally sound bridges. Soon, guilds were established with the sole focus of building longer and stronger bridges to support imperial armies on their way to conquer new territory.

Most bridges are crossed quickly, but Ponte Vecchio in Florence, Italy, the city’s oldest bridge, is home to stores cantilevered on the bridge’s sides, which makes for a more leisurely stroll. (Credit: Perituss, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the next few centuries, truss bridges caught on, leveraging a series of triangular load-bearing beams. By the time the Industrial Revolution arrived, these tried-and-true designs provided the right blueprints for bridge-building to progress, both in terms of how quickly the bridges were built, and also in terms of the weight they could bear.

Suspending Disbelief with New Designs

Bridges now carried more than just pedestrians and carriages – they supported trains carrying heavy cargoes and serving as essential infrastructure of national and international economies. The invention of the steam engine and, later on, the Bessemer Process for mass producing steel, facilitated the production and transportation of iron and steel all over the world. These materials, along with concrete, provided inspiration and means for engineers to attempt more ambitious designs.

Then came the Menai Bridge, a structure that would fundamentally change the future of bridge-building worldwide. When it was erected in 1826, this suspension bridge connecting Anglesey Island with the Wales mainland was the first modern bridge of its kind. Although the fundamentals of the suspension bridge go back to bamboo and vine structures, this 579 foot-long bridge made use of wrought iron and a timber deck to cross the Menai Strait.

At this point, aspiring engineers like John Augustus Roebling decided to build their careers around the principles of the suspension bridge. Roebling went on to create wire rope suspension bridges, including the Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge between New York and Canada, the John A. Roebling Suspension Bridge across the Ohio River at Cincinnati, and, most famously, the Brooklyn Bridge.

Roebling is known as the mastermind behind the Brooklyn Bridge, but he never saw it completed. While he was surveying the site for the bridge, a ferryboat crushed his foot, resulting in its amputation and, shortly thereafter, a deadly bout of tetanus.

More recent bridges have continued to push the limits of bridge design. When San Francisco’s iconic Golden Gate Bridge was completed in 1937, it was the longest and tallest suspension bridge in the world. The record for the longest bridge has since passed on to the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge in China – a 100-mile-long high-speed rail bridge that was built in just four years. The world’s tallest bridge today is the Millau Viaduct.

Burnt Bridges (Mostly Metaphorical)

For the most part, the story of bridges is one of ingenuity, invention, and an insatiable drive to do more and more impressive things. However, with the building of bridges came questions about site selection, costs and how communities would change in the aftermath of construction.

Catalysts for Disputes

The construction of bridges takes years, if not decades, after the idea is initially proposed. Not only do engineers and architects have to file an incredible amount of paper and craft structurally sound plans, they have to work within budgetary constraints and stay compliant with regulations – sometimes, two sets from two different nations.

Another sore spot for bridge-building is whether a bridge will be public or private. In the U.S., there are more than 620,000 public bridges over 20 feet long. Belonging to the public and being a part of public roads, those bridges are maintained by federal, national, and local governments. While proportionally smaller in number, private bridges in the U.S. are bone of contention for local communities that want to utilize the spans but recoil at expensive tolls.

Ambassador Bridge at the Detroit/Windsor Border. (Credit: Alyssa Black, via Wikimedia Commons)

For example, the Chicago Skyway between Illinois and Indiana was leased to a private entity by the City of Chicago in order to secure cash for the city. The current majority owner of the Skyway is an Australian operations group, which has prompted many to question the role international entities should play in bridges that don’t affect their communities.

Likewise in Detroit, Michigan, the privately owned Ambassador Bridge connects the U.S. to Windsor, Ontario, in Canada. This bridge’s prime location makes it one of the busiest border crossings between the two countries. A new publicly owned bridge, the Gordie Howe International Bridge is currently under construction in close proximity, providing an alternative to the private toll bridge that has dominated the border.

Tempting Targets in War

Bridges have been, and likely will always be, targets during times of war. Taking one out can be a strategic move that limits an enemy’s ability to navigate and get necessary supplies. Because the world wars in Europe had both civilian and military targets, destroying bridges was a tactical move used by all sides.

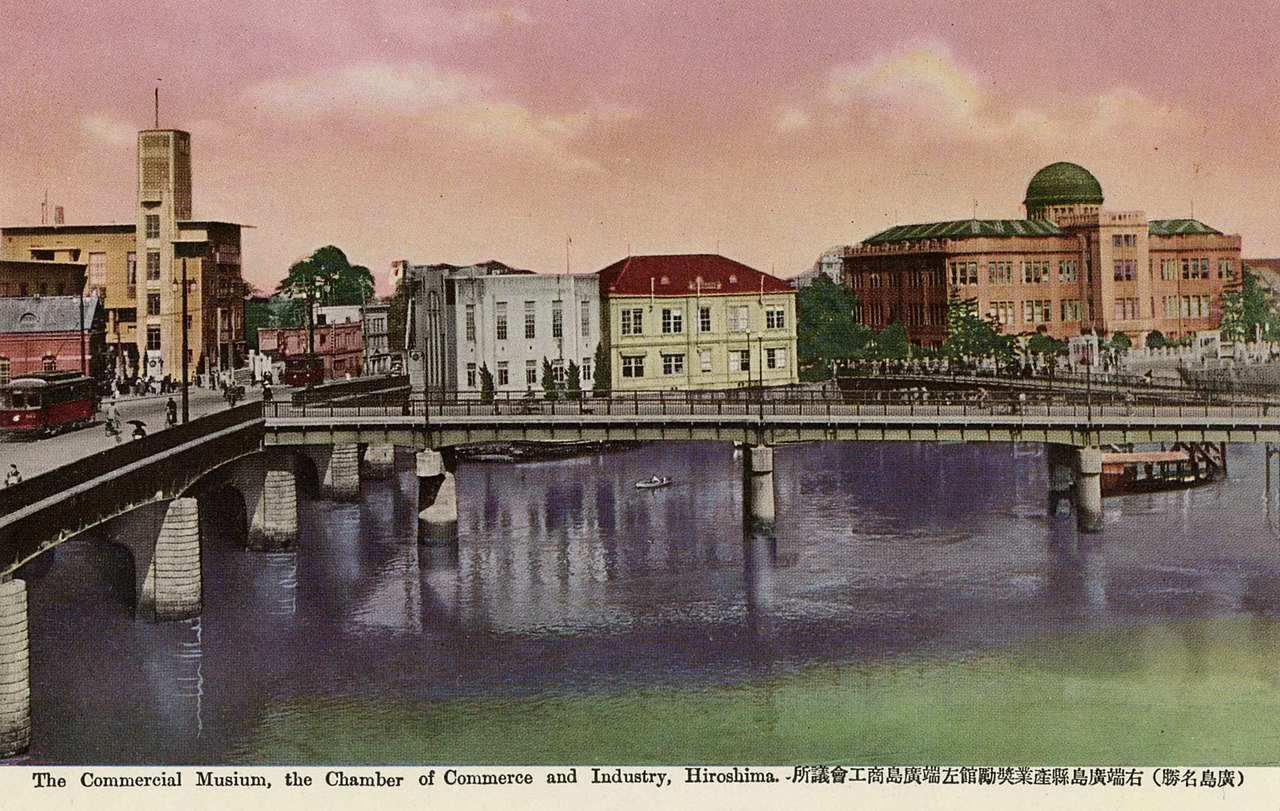

For example, during World War II, many bridges in both the European and Pacific theaters were destroyed. At one point, the Nazis even tried to blow up one of their own bridges, the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen on the Rhine, before it fell into Allied hands. They caused enough damage that it did eventually collapse, but not until after it had been captured. The Allies also bombed many bridges during the war, notably including the Recco Bridge in Italy and the Bridge on the River Kwai in Thailand. And when the Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the Aioi Bridge was the bombardier’s target for its proximity to the city center.

Aioi Bridge, Hiroshima, pre-WWII (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

More recently, a 12-mile-long bridge between Russia and Crimea has been attacked repeatedly by Ukrainian forces. The target has both symbolic and strategic importance to both sides in the war, and it is vital to Russia's ability to supply its troops in Crimea.

Potential for Negative Economic Impacts

While bridges can attract hordes of newcomers to areas in which they might otherwise have never set foot, they can also redirect traffic away from certain areas. Towns like Drawbridge, California, that were designed around the railroad traffic coming through them were abandoned once new bridges were built making travel to cities faster than ever before.

Ghost town of Drawbridge, California, seen from train tracks passing over the Don Edwards Wildlife Refuge (Credit: Dargasea, via Wikimedia Commons)

Another downside to being home to a bridge is the potential for collapse. Examples include the I-35W Mississippi River bridge and Atlanta’s I-85 bridge, both of which collapsed during rush hours about 10 years apart. And, in 2024, Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge was damaged by a cargo ship that lost power. The single blow from the ship to one of the bridge’s pillars resulted in the collapse of the 8,636 foot-long bridge.

The history of bridges involves advances in materials, methods, and technologies. It is also a story of construction and destruction, connection of communities and division between them, Yet, humanity’s harnessing of natural resources, crossing of raging rivers, and spanning of deep ravines remains something most everyone can marvel at. No matter the politics, the targeted attacks of war, or the devastating accidents, the grandeur of bridges prevails.

Ω

Daisy Dow is a contributing writer for MagellanTV. Originally from Georgia, she now works in Chicago as a tour guide and freelance writer focused on history, small businesses, and marketing strategies.

Title Image: Stone bridge in Rakotszee, Germany (Source: Unsplash)