Human beings have long wondered if we’re alone in the Universe. For ancient Greek philosophers, this turned into a zero-sum debate.

◊

Here we are, specks in our little sliver of the Universe, thinking about whether life exists somewhere else. Let’s take a moment to consider scale, and the fact that our little home, Earth, is teeny tiny when compared with the Sun.

Now consider the fact that scientists estimate the Universe consists of trillions of galaxies. Trillions! Our own, the Milky Way, is pretty huge. So, trillions of galaxies means the Universe is … indescribably enormous.

Add to that the fact that our observable slice of the Universe is pretty small compared with all there is, which is estimated to have a diameter of something between 92 billion and 23 trillion light years, depending on who's counting. (According to Astronomy.com, we can see to about 46 billion light years away.) Within that slice, consider the possible permutations of galaxies and all the stuff that makes up a galaxy, which is, NASA tells us, “a huge collection of gas, dust, and billions of stars and their solar systems, all held together by gravity.” So, perhaps it’s not a stretch to guess that Earth’s life forms are not the only ones in such a vast cosmos.

Though the Universe is 13.8 billion years old, we can see up to 46.1 billion light years away because the Universe has been expanding since the Big Bang.

Of course, we don’t need to look far from home to begin thinking about life. Here on Earth, we find life in places humans – and loads of other creatures – can’t survive. For example, scientists have found microbial life in tar, and a certain type of bacteria resists massive amounts of radiation. Various creatures live in the waters around hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the Pacific, where the crushing weight of the water would flatten most things, let alone the scalding water near the vents. Oh, and the Dead Sea isn’t really dead – there are microbes that happen to love all the salt that would kill off most aquatic life.

But we didn’t know about most of these organisms until relatively recently. Ancient peoples couldn’t have known about them. And when they looked to the heavens, did they wonder whether there might be anything alive – like us – up there?

Check out Other Earths on MagellanTV.

To Debate Life, Philosophers First Define It

In fact, the Ancient Greeks, those extraordinary influencers of Western and Middle Eastern thought and culture, were among the first to theorize about life on other planets. The ancient Greeks, in other words, are not just ancient history!

As we do today, ancient Greek thinkers disagreed about the possibility of life elsewhere in the Universe. Some argued that we here on Earth are alone, while others argued that we’re likely not the only life in the cosmos. These positions emerged out of theories about what there is and how it got that way – you know, the sort of thing most people think about at the weekend.

One of the most influential of ancient Greek concepts is that nature isn’t random, and one of the most famous adherents of this view is Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BCE. Everything, Aristotle argues, seeks its end. In other words, nature is purposeful. Consider it this way: Aristotle thinks a thing has within itself the potential to actualize its ultimate end. Hence, the frog is in the tadpole, essentially directing its development in advance.

We could describe the process this way: The tadpole aims at becoming a frog, which is its goal or telos. (It doesn’t aim, for example, at being a kitten, since it doesn’t have the potential to be one.) Even inanimate objects have purpose; a stone “goes to ground,” because it seeks its natural place, which is the center of Earth. Aristotle didn’t have the concept of gravity as we know it, let alone the mathematical formula, but he provided an impressively thorough theory explaining how a thing’s “internal principle” moves it toward its “natural place.”

Aristotle, University of Freiburg, Germany

(Credit: 1195798, via Pixabay)

To help us understand the concept, we can follow Aristotle’s distinction between instrumental (a means to a further goal) and final ends (the goal itself). Take, for example, human teeth. Considered in isolation from the whole body, the purpose of teeth is to tear and grind. In connection to the whole, teeth are a means to securing nourishment. So, Aristotle’s view is that nourishment is itself a means to a further end, and so on until the goal is achieved. In the case of a human being, that purpose is the good life, or eudaimonia, which is loosely translated as happiness but is more accurately understood as flourishing.

Not all the Ancient Greeks endorsed this sort of teleological view. Epicurus, who also lived in the 4th century BCE but was younger than Aristotle by about 20 years, held that the Universe is mechanical. Epicurus adapted this view from his predecessor from the previous century, Democritus, who claimed that reality consists of atoms moving about in the void.

Epicurus, Musei Capitolini, Rome (Credit: BBC.com)

Epicurus thinks a mechanistic account of events obviates the need for divine causes. So, since divine causes are often associated with thinking about ultimate ends, Epicurus’s view dispenses with teleology. That said, it’s worth noting that Epicurus also has a vision of human happiness, which is the pleasure associated with freedom from physical and psychic distress.

A Zero-Sum Debate on Life Arises

To start the debate, let’s talk about atoms. At the turn of the 20th century, physicists thought that the atom was the smallest material unit. Indeed, “atom” is the transliteration of (you guessed it!) the Greek word for “uncuttable.” Long before physicists thought about the fundamental stuff of the Universe, the ancient Greek thinkers, Leucippus and Democritus – the so-called Atomists – developed a strikingly sophisticated theory of the cosmos.

According to the Atomists, the Universe is constituted by atoms and the void. Atoms continuously move through the void, which is “the empty” (but not nothing). Moreover, atoms are materially uniform; the only differences among them are size and shape. They can be as large as the cosmos or too small to see, and their shapes vary, which is why their collisions with each other as they move about the void have different results. Upon collision, atoms either bounce off each other or cluster together. When they combine, they are still separated by the void, and so do not become a new, larger uncuttable. In this way, all observable objects are constituted and are disintegrated.

Despite a lack of sophisticated instruments, the ancient Greeks anticipated a variety of contemporary scientific theories.

Aristotle rejected Atomism. For our purposes, his chief criticism was against the Atomists’ view that the Universe is mechanical, rather than teleological. That’s because the atoms do not have a reason for being, an essence to actualize. Instead, they merely bump into each other and move away as necessity – not purpose – dictates.

Aristotle’s own geocentric view of the cosmos held sway for centuries. Indeed, it was not until Copernicus proposed a heliocentric Universe in 1543 that the Aristotelian picture was upended. Aristotle’s teleological view of (earthly) nature extends to the rest of the cosmos. It is in heavenly bodies’ natures, Aristotle thought, to move as they do. So, while on Earth, things like rocks move in a straight line toward the center, celestial bodies move in circles. Earth, also spherical, sits at the center of the cosmos, surrounded by planets and stars.

(Credit: University of Rochester, Dept. of Physics and Astronomy)

Earth is at the center of the Universe, Aristotle contends, because it is constituted by the heaviest element. According to Aristotle, and following the 5th century BCE Greek thinker Empedocles, there are four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. The heaviest elements are closest to the center, while the lightest are farthest away. Were the Universe infinite, Aristotle thought, there would be no center, and so no clear goal toward which the stuff of the Universe moves. Fair enough, except that, as we know, Aristotle was wrong. But does this mean he was also wrong about the possibility of life elsewhere in the cosmos? First, let’s find out what he thought.

Given the geocentric picture Aristotle paints in On the Heavens, no other Earth is possible. The Sun and Moon – everything out there – move around Earth, which is fixed and stationary at the center of it all. Aristotle’s view, therefore, is that life is exclusive to what Joni Mitchell calls our “marbled bowling ball.”

Not so for Epicurus. “There are infinite worlds,” Epicurus writes, “both like and unlike this world of ours.” The possible permutations of such worlds imply life elsewhere. To put it another way, the endless atomic collisions mean that worlds come to be (and pass away).

Following Democritus, Epicurus conceived the Universe as both infinite and eternal. It is infinite, Epicurus thought, since setting a limit suggests an “other side.” More specifically, given that an infinite number of atoms are made of one kind of stuff, and, given that these atoms move about in an infinite void, it follows that the same material stuff exists everywhere. So, since Earth is just a particular configuration of atoms, it’s plausible, at least in principle, that there could be life elsewhere in the Universe.

Epicurus is the source of Epicureanism, a philosophy best known for advocating pleasure, which Epicurus does not equate with gluttony.

Moreover, since something cannot come from nothing, Epicurus argues, the Universe must always have existed. On this latter point, both Epicurus and Aristotle agree – to a certain extent. Aristotle argued that the cosmos must be eternal, since it is perfect; and it is perfect, because it is unique, finite, and spherical – the most perfect shape. Epicurus did not claim perfection for his Universe, from which we might infer a Universe that is effectively incomplete – it is without boundaries. An infinite Universe consists of all possibly existent things.

It’s All Greek To Me

Though today’s cosmologists have largely left the likes of the ancient Greek philosophers to the history books, only the intellectually reckless would dare to underestimate their profound influence on our theoretical frameworks. We owe many of the advances in our understanding of the tiny sliver of the Universe we call home to those thinkers who arrived at their conclusions without the aid of extraordinary technologies and mathematical systems. How we conceive the nature of the Universe (teleological or mechanical?) means that Aristotle and Epicurus are still very much with us – and will likely be for generations to come.

Ω

Mia Wood is a professor of philosophy at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, California, and an adjunct instructor at Bentley University and the University of Rhode Island. She is also a freelance writer interested in the intersection of philosophy and everything else. She lives in Little Compton, Rhode Island.

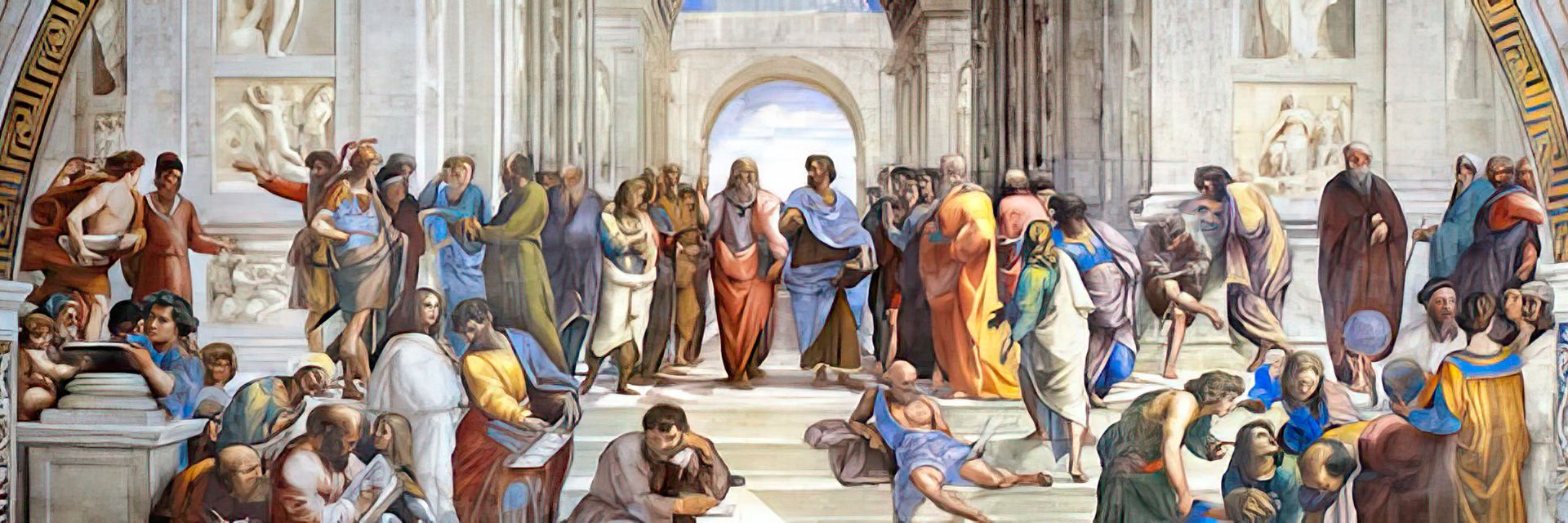

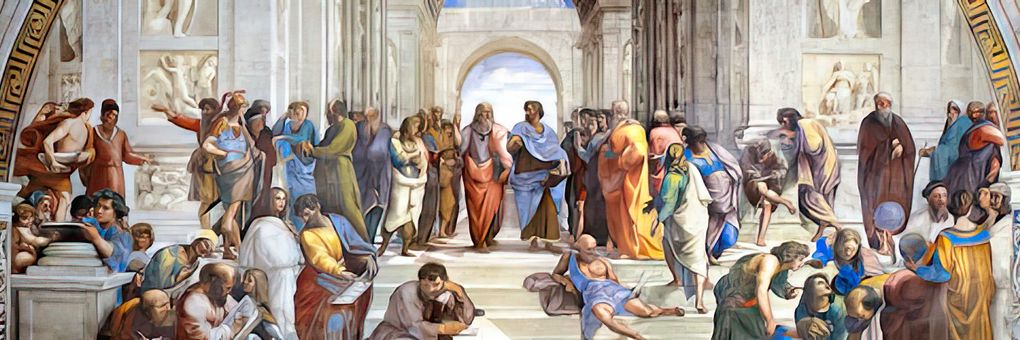

Title Image: Detail of The School of Athens, painting by Raphael (Apostolic Palace, Vatican City), via Wikimedia