A New York dentist and inventor wanted to alleviate human suffering, but his legacy was tarnished by his most recognized invention: the electric chair.

◊

In Buffalo, New York, at the beginning of the 1880s, a steamboat engineer, dentist, and inventor named Alfred Southwick was interested in the possibility of using low-voltage electricity to reduce the pain routinely experienced by his patients. In 1881, his research took a fortuitous, albeit horrifying, turn when he read the widely reported story of a Buffalo dockworker who accidentally died by electrocution while attempting to shut down a power dynamo.

Though tragic for the victim and his family, Southwick discerned a silver lining to the incident: The dockworker had reportedly died almost instantly, and apparently without pain. At a time when capital punishment was common and usually inflicted by hanging – which too often resulted in ghoulish malfunctions – could electrocution offer a more humane alternative?

For more on the history of the electric chair, check out the MagellanTV documentary "The Chair."

Southwick the Overachiever

Born in 1826 into a prominent Ohio family that traced its American roots to the Mayflower, Alfred Southwick demonstrated a keen intellect from an early age. His first career was as a steamboat engineer, a profession at which he excelled even without a college degree, rising to a position as chief engineer.

Later, Southwick turned his interests to dentistry in Buffalo. After serving an apprenticeship, his new career flourished, and he put his engineering experience to use designing appliances and devices for dentistry. Eventually, he became a clinical professor of operative techniques and mechanical techniques at the University of Buffalo School of Dentistry.

Inventing the Electric Chair

For several years after the unfortunate death of the Buffalo dockworker, Southwick worked on his initial designs for the electric chair. In the late 1880s, he was appointed to the New York State Commission on Human Execution, a position from which he advocated for the efficacy and relatively humane method of capital punishment using his invention.

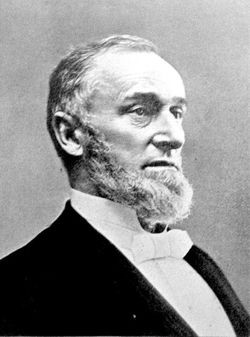

Alfred Southwick (Public domain via Find a Grave)

As it happened, another member of the commission was Thomas Alva Edison, America’s most famous inventor. Edison was locked in a ruthless competition with George Westinghouse to make electricity widely available for both household and industrial use – and to reap the enormous profits that would naturally ensue. When Southwick approached Edison for advice concerning design challenges, Edison suggested that he talk to Westinghouse instead.

The Electric Chair Gains Acceptance

Southwick’s electric chair design faced initial skepticism and opposition. While proponents argued that the electric chair provided a more humane means of execution, critics raised concerns about the potential for pain and suffering inflicted by electricity. Eventually, though, the electric chair was adopted by some jurisdictions for putting people convicted of capital crimes to death.

On August 6, 1890, New York became the first state to use the electric chair for an execution, but it was not Southwick’s design that was used. Rather, a design secretly backed by Edison was employed. And, to make matters worse, the execution did not go well. The victim, a convicted murderer named William Kemmler, was indeed killed, but, despite Southwick’s protestations to the contrary, the execution was a gruesome affair. Still, the electric chair’s use in New York continued until 1963 when it was deemed “cruel and unusual punishment” by state courts.

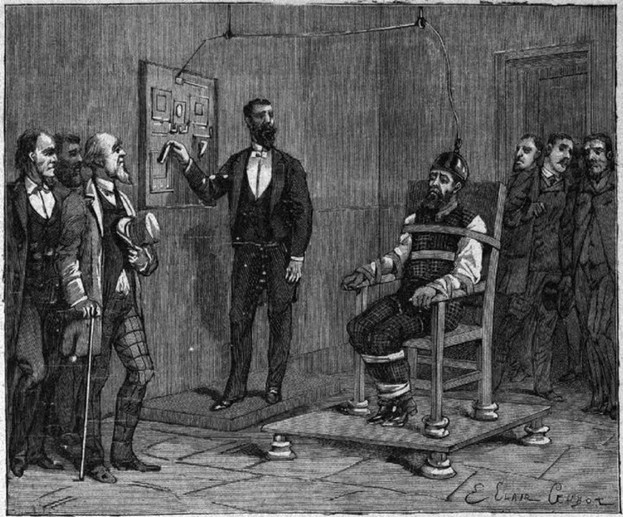

The moment before a condemned man’s execution in the electric chair (Source: Death Penalty Information Center)

Southwick’s Tarnished Legacy

In later life, Alfred Southwick could not escape his association with the invention of the electric chair. He continued to advocate for capital punishment by electricity, arguing that it was more humane than other methods. But critics did not relent. The New York State Dental Society went so far as to decline to recognize the University of Buffalo School of Dentistry, ostensibly because Southwick had not actually earned a degree in dental medicine.

Southwick died uneventfully in 1898 . . . of natural causes.

Ω