Philosophers have been dreaming about a universal world brain – something that could synthesize and democratize all human knowledge ? for centuries. The Internet may be the closest we’ve come to realizing this ambition, but its rise has also led to unprecedented complications, including one dramatic copyright-related lawsuit that resulted from Google’s World Brain project.

◊

H. G. Wells spent much of his childhood escaping his family’s poverty by immersing himself in the world of books. Perhaps it makes sense that Wells was responsible for conceptualizing the most ambitious information system of all time.

In a series of essays dating from 1936-1938, Wells outlined what he called the “World Brain.” His vision: a massive, exhaustive encyclopedia that would consolidate all human knowledge, making all books universally available and eventually ushering in an era of world peace.

Flash forward to the 21st century. World peace certainly has not been achieved, though war has changed form. The Internet allows people around the world to access almost any information as long as they have an electronic device and a WiFi connection. Even so, it’s become clear that the Internet tends to proliferate fake news and often reinforces human biases (a far cry from any utopian vision of a universal information source).

However, in the early 2010s, Wells’ dream of a universal library nearly came to life, thanks to the Internet’s greatest search engineers – the tech gurus at Google. Inspired by his vision, they decided to create a digital World Brain that would consolidate all the books in the world onto Google’s database. Somewhere along the way, though, something went very wrong. By the end of Google’s efforts to create its version of the World Brain, it found itself slammed with lawsuits, having enraged countless people who didn’t want Google uploading their copyrighted work to the Internet.

In a way, Google’s library project was like so many utopian ideals – it sounded promising in theory, but, in practice, it wound up authoritarian and oppressive. So what went wrong with Google’s efforts to create their own version of a World Brain? And what can it teach us about the Internet (and even ourselves?)

Before the World Brain: A Brief History

H. G. Wells was a pioneer, but he wasn’t the first or last to theorize a concept like a World Brain. People have always been fascinated by the idea that there might be some kind of interconnected force, something capable of consolidating and universalizing all human knowledge.

H. G. Wells, c. 1890 (Credit: Frederick Hollyer, via Wikimedia Commons)

H. G. Wells, c. 1890 (Credit: Frederick Hollyer, via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1737, Andrew Michael Ramsay described one of the objectives of freemasonry as “... to furnish the materials for a Universal Dictionary.” According to Ramsay, “By this means the lights of all nations will be united in one single work, which will be a universal library of all that is beautiful, great, luminous, solid, and useful in all the sciences and in all noble arts. This work will augment in each century, according to the increase of knowledge.”

Ramsay’s argument was the genesis of France’s Encyclopédist movement, which aimed to consolidate all the world’s resources into one entity. Like many Enlightenment philosophers, the Encyclopédists promoted secular thought and valorized reason and tolerance. They ultimately created the Encyclopédie, a massive 17-volume reference work that – due to its general preference for science over religious ideals – enraged the Church.

All these movements may have ostensibly been trying to codify the world’s knowledge, but they also speak to a much deeper human desire: the imperative to connect with others. This was inherent in the ethos of what would become H. G. Wells’s World Brain.

H. G. Wells Conceptualizes the World Brain

From the time he was a boy growing up in Kent, England in the 1860s, H. G. Wells was envisioning alternative futures. In his writing, he was an early science fiction pioneer, creating some of the foremost early works about time travel and invisibility. His first novel, The Time Machine, brought him instant success, and further works uploaded topics like alien invasions into the mainstream consciousness. In addition to his love of alien life forms and sci-fi drama, Wells often wrote about politics and class struggle.

A lifelong socialist, Wells campaigned as a Labour Party candidate in England and met with Leon Trotsky and other foremost far-left leaders during his lifetime. In his writing, Wells allowed his visions to truly take flight. The Time Machine depicts a future with only two races: the Capitalist and the Labourer. In The New World Order, Wells also advocated for a single, global, non-central government.

“Wells was appalled by the decentralised nature of America’s locally oriented party and country-courthouse politics. He was aghast at the flamboyantly corrupt political machines of the big cities, unchecked by a gentry that might uphold civilised standards. He thought American democracy went too far in providing leeway to the poltroons who ran the political machines and the ‘fools’ who supported them.” — Fred Siegel, H. G. Wells: The Godfather of American Liberalism

Wells’s desire for a universal power structure pervaded all his work. Like many philosophical people, the believed that humans are fundamentally interconnected, and he believed that our existence is not random; rather, he thought, it exists in patterns that have the potential to cohere and even unify.

Much of Wells’s work is scattered with seeds of the idea that would become the World Brain. In his essay “Brain,” Wells wrote of a “world synthesis of bibliography and documentation with the indexed archives of the world.” This synthesis, he wrote, “foreshadows a real intellectual unification of our race. The whole human memory can be, and probably in a short time will be, made accessible to every individual.”

Wells was careful to emphasize that his World Brain encyclopedia should not be a continuation of the already oppressive and restrictive university structure. Rather, it should allow information to reach all people, no matter their status or class. “The encyclopaedias of the past have sufficed for the needs of a cultivated minority. They were written ‘for gentlemen by gentlemen’ in a world wherein universal education was unthought of, and where the institutions of modern democracy with universal suffrage, so necessary in many respects, so difficult and dangerous in their working, had still to appear,” wrote Wells in a statement that certainly resonates today.

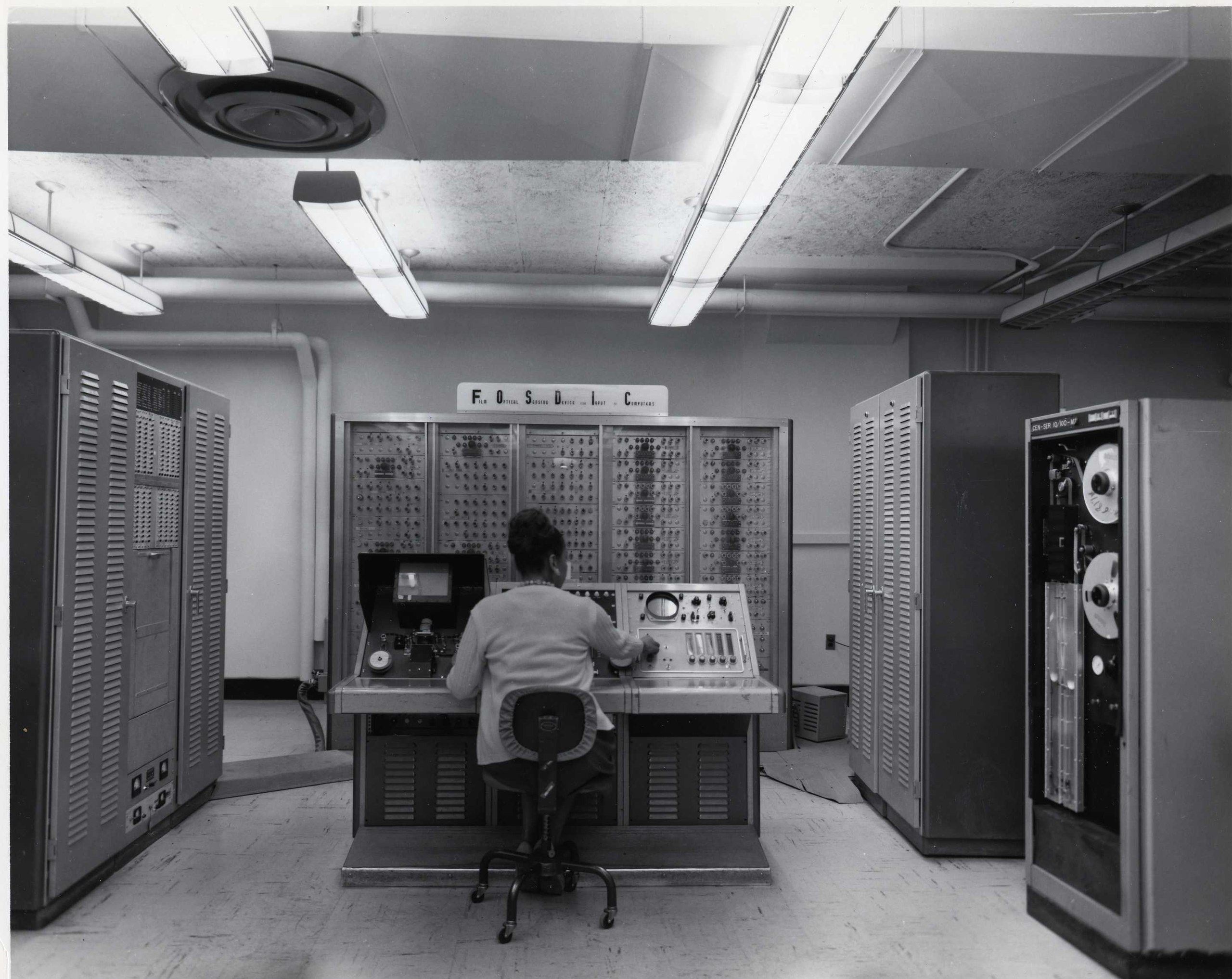

Film Optical Sensing Device for Input to Computers (FOSDIC), 1960 (Credit: U.S. Census, via Wikimedia Commons)

Despite the clarity of his statement, Wells’s ideas are often used to justify an irrational faith in an aristocratic, exclusive and intellectual class. It’s ironic (though perhaps not surprising) that Wells’ World Brain – a concept born out of socialist ideals – was eventually usurped and distorted beyond recognition by a little corporation known as Google.

The World Brain in Modern Times

By the 1960s, people were already beginning to imagine that Wells’s World Brain would look something like a giant supercomputer. In Profiles of the Future, Arthur C. Clarke predicted that the World Brain would involve a universal library and a superintelligent computer that humans could work with to solve problems.

“The idea of society as being similar in many respects to an organism or living system is an old notion. In this metaphor, organizations or institutions play the role of organs, each performing its particular function in keeping the system alive.” —Francis Heylighen, Conceptions of a Global Brain

By the 1980s, as the digital landscape was gaining power, Wells’ World Brain took different forms. The term “global brain” was first coined by Peter Russell in The Global Brain. He argued that human beings have reached an evolutionary crossroads. He theorized that humans were close to reaching a collective consciousness, and he proposed that, in conjunction with a global spiritual awakening, these developments could save the human race from ourselves.

By the ‘90s, the concept of a massive, universal web of documents was being realized with the World Wide Web. Media theorists began to imagine a world where all information was available for free, where individualism could be replaced by collectivism, and where humans essentially worked together.

The World Brain in the Internet Age: Google Attempts to Consolidate All Information

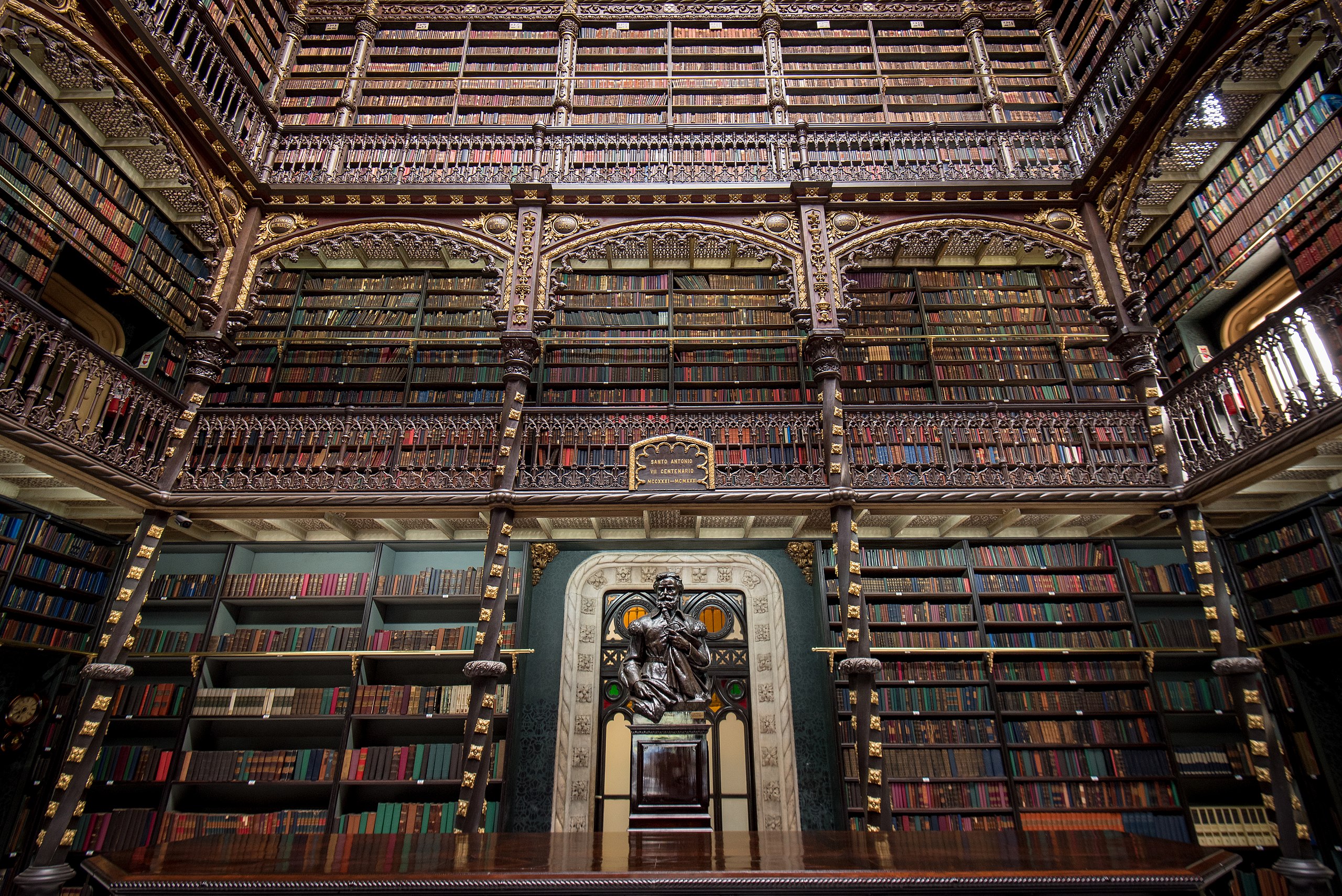

Around 2002, Google was well on its way to achieving its current status—and it had scanned a lot of books. So far, Google has scanned over 30 million volumes, but their original plan was to scan a lot more. As part of their Google Books Library Project, the company collaborated with major universities like Stanford and Harvard, planning on melding entire libraries into their database. Eventually, the company wanted to scan every volume ever created, and to upload even out-of-print books and old periodicals to one massive, searchable entity.

Royal Portuguese Cabinet of Reading, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Credit: Donatas Dabravolskas, via Wikimedia Commons)

Not surprisingly, when Google began scanning books, it ran into copyright issues almost immediately. In 2005, they were sued by the Authors Guild. By 2008, the company had reached a “Proposed Settlement Agreement”—which also had its critics, sparking protest among organizations including the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

By 2013, the Authors Guild Inc. Vs. Google Inc. was dismissed in court, and Google was officially allowed to upload parts of certain books to the public domain. While this was read as a victory for Google, it still left them with certain restrictions, which you can see on the database you might now know as Google Books.

Why did Google’s attempt to codify and disseminate all knowledge fail, and what does this failure mean for Wells’s World Brain idea? One of the main reasons Google’s philosophy foundered is simply the fact that Google – a deeply secretive for-profit company – appeared to be developing a monopoly on information. The profound suspicion its initiative faced revealed that achieving a truly equitable World Brain might be impossible when the brain is being run by a secretive corporation, or by an entity invested in monetary gain at all.

The Future of the World Brain

Today, you can get almost any information you want for free on the Internet, and every day more information is uploaded. Perhaps we already possess something close to a World Brain. Maybe you are reading an article on it right now.

Lately, the World Brain idea (often referred to as the “Global Brain” concept) is having a resurgence. As the AI revolution looms, people are wondering how artificial intelligence might allow us to connect more deeply with the world around us. Many believe that Wikipedia – a democratically created and universally free source – is the closest thing on the Internet to Wells’s Word Brain. But others have even more ambitious interests. The MIT Center for Collective Intelligence has started to study the concept of how a global digital brain might be programmed to best synthesize all human information. And Elon Musk has founded the company Neuralink, which aims to create a machine that is implanted in the human brain and lets users instantaneously access all the information available on the Internet.

If all this sounds a little creepy to you, you’re not alone. Despite the beauty of the World Brain concept, it’s hard not to imagine that a World Brain might be used as a mechanism for surveillance, groupthink, and profit. After all, every invention is a reflection of its maker, and technological World Brains will inevitably reflect human biases. Why should a World Brain be any more ethical and responsible than the human mind itself?

Ω

Editor's Note: Two sentences in the opening section of this article that referred to and included a link to a MagellanTV documentary that is no longer available have been removed.

Title image: The concept of the human brain by Tryfonov via Adobe Stock.