Is Pluto a planet? While planetary scientists insist it still is, astronomers named it a “dwarf planet” in 2006. Who is right? Resolving the question means agreeing on what a planet is.

◊

Pluto is not a planet. Well, not exactly. Its classification by the International Astronomy Union (IAU) changed in 2006 from “planet” to “dwarf planet,” along with a few other orbiting orbs floating beyond Neptune, the last of the eight “classical” planets in our Solar System.

Now, what accounts for this – let’s call it what it is – demotion? All our lives (or most of our lives) until 2006, children were taught about the nine planets of the Solar System, from fiery Mercury all the way out to icy Pluto. And so what if tiny Pluto was the smallest of the lot? Great things, like our planets, can come in small packages. Even though Pluto is just half the size by diameter of Mercury, the smallest of the remaining eight, its minuscule scale wasn’t found to be objectionable . . . until it was. Here’s what happened.

Explore the Pluto controversy and more in Pluto Rediscovered, from the Naked Science series on MagellanTV.

The Life of Pluto, the Planet: b. 1930 – d. 2006

One day in February 1930, Clyde Tombaugh, an astronomer at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, using a new technique involving photographic plates and a microscope, spotted an anomaly in the heavens beyond Neptune. Its movement proved to him, and then the world, that there was something interesting out there. And so it happened that Clyde Tombaugh serendipitously discovered Pluto, which was recognized as the ninth, and most distant, planet of the Solar System for more than 75 years. But sometimes things change, right? And this is especially true in science.

Clyde Tombaugh in 1928. (Wikimedia Commons)

By the 1990s, astronomers learned that Pluto lies in a zone called the Kuiper Belt – and it has lots of company. Virtually countless icy orbs left over from the formation of the Solar System inhabit the belt, and Pluto joined a classification known as “trans-Neptunian objects.” When another floating body was found that was even larger than Pluto – but wasn’t considered an actual “planet” – an outcry arose among astronomers to address how “planethood” was defined. Either loosen the definition to expand the number of objects called planets, or change it expressly to exclude this growing class of large “plutinos.”

What is a plutino? They are trans-Neptunian objects that look and act like Pluto, are generally in the range of Pluto’s mass, and would likely become planets if a definition that included Pluto were approved.

This clamor for clarification led to calls in the early 2000s to refine the definition of “planet.” So at the IAU’s 2006 conference in Vienna, competing proposals were brought up for a vote. One faction called for adding many more objects to the planetary roster; the other called for a tighter description that would keep the number of classical planets small. The advocates for a tighter standard prevailed. As a result, Pluto and several objects formerly labeled asteroids were officially reclassified as “dwarf planets,” a new category meant to satisfy people on both sides of the debate.

But the result was far from satisfying to opponents of the new standard. Within days, a group of 300 planetary scientists from institutions worldwide had signed an open letter to the IAU protesting the redefinition and petitioning that the decision be rescinded. And it seems that, to date, the intensity of the controversy has not waned.

Planetary Scientists vs. Astronomers in a Battle over a Definition

Founded in 1919 and headquartered in Paris, the International Astronomy Union oversees standards for the practice of astronomy. Astronomers observe the Solar System and the vastness of space beyond to uncover the mechanics of the Universe. They are joined in their search for knowledge by planetary scientists, who primarily focus on the geological and chemical processes of the planets orbiting the Sun.

In the corner of the astronomers, we have Mike Brown, a professor at the California Institute of Technology, who identifies himself on social media as “plutokiller,” and who notably wrote the self-explanatory How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming. In the 1990s, Brown was on the team that discovered the object now named Eris, the dwarf planet larger than Pluto, which piqued his interest in clarifying the definition of a planet and led him to lobby the IAU to make it happen.

Mike Brown is deeply involved in the search for another as-yet-undiscovered planet beyond Neptune. He calls it Planet Nine.

In the corner of the planetary scientists, we have numerous challengers. One who is mentioned repeatedly is Dr. Philip Metzger, a professor at the University of Central Florida. With a team of collaborators, he is the lead author on a scientific paper arguing that the IAU’s 2006 decision was erroneous and supported by specious data.

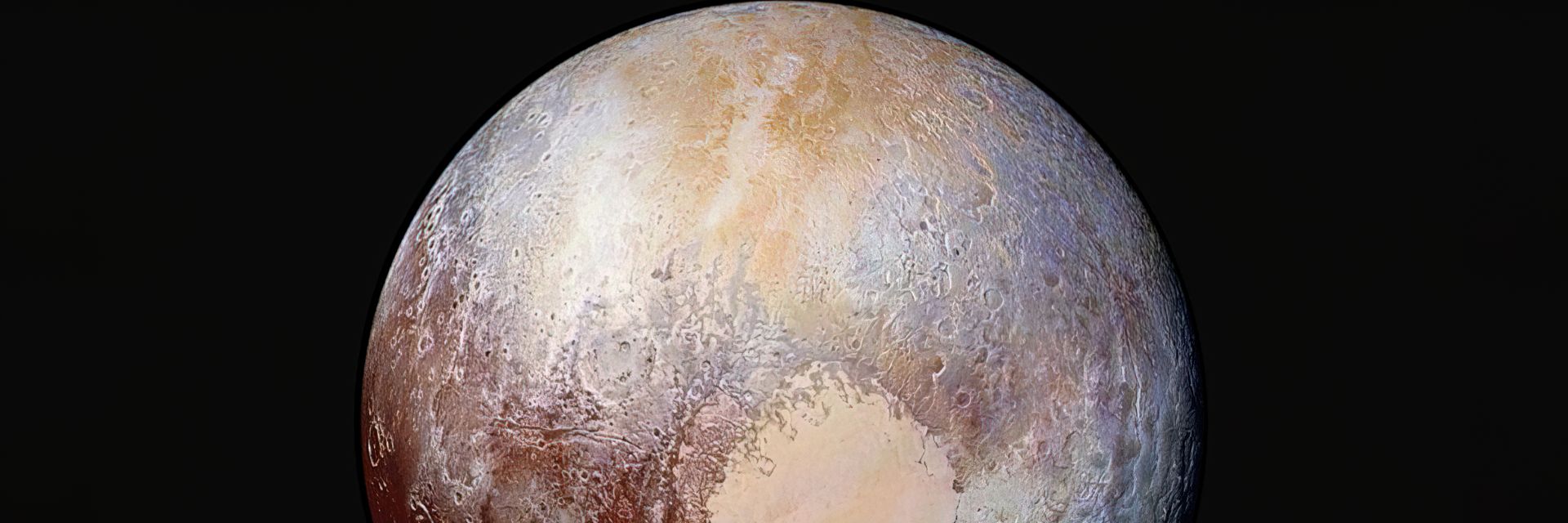

Joining Metzger in his crusade is space scientist Alan Stern, principal investigator of NASA’s 2015 New Horizons mission, which studied Pluto and returned stunning images from its flyby that emphasize Pluto’s many intriguing features. Stern signed Metzger’s paper as a co-author on the research.

“True color” image of dwarf planet Pluto. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Alex Parker)

The Crux of the Argument Is This

The dispute all boils down to the divergent perspectives of the two separate groups of scientists. Stern and others argue that complexity should be the prime qualifier, and Pluto, with its possible underground ocean, wispy atmosphere, and abundance of frozen methane glaciers, makes it a prime candidate for planethood. Metzger says Pluto is “the second-most complex, interesting planet in our solar system,” even more complex than Mars. It is surpassed only by Earth.

While Metzger believes his paper successfully refutes the IAU’s decision, even claiming it is “harmful to science,” astronomers look at the Pluto question quite differently. Rather than basing classification on an orbiting object’s complexity, astronomers approved a tripartite definition of “planet” that neatly excises Pluto from the list. To qualify, an entity must:

- Orbit the Sun;

- Be round, or nearly so, as a result of gravity and mass; and

- Clear its orbital neighborhood.

It’s that last qualifier, “clearing its orbit” of other things in its path, that excludes Pluto and places it in a league with hundreds of other Kuiper Belt objects. Because of its insufficient mass, Pluto (and its similar “dwarves”) just doesn’t qualify as significant enough to have a cleared orbit and qualify for membership in the exclusive club of eight “classical” planets.

Should Pluto Be a Planet? Is There a Clear Winner?

Metzger has the support of other planetary scientists, as well as a broad swath of top scientists and administrators at NASA. In 2019, then NASA chief Jim Bridenstine said, “In my view, Pluto is a planet. . . . It’s the way I learned it, and I’m committed to it.”

On the other hand, astronomer and former IAU president Ron Ekers has tried to tamp down the disagreement by stating, “This is not a vote about science. The vote . . . is about an agreement on how you name things.” On the same side, but for different reasons, is famed astrophysicist and science educator Neil deGrasse Tyson of the Hayden Planetarium, who strongly supports Pluto’s reclassification on the grounds that the dwarf occasionally crosses paths with Neptune. As he told Stephen Colbert on his late-night program, “That’s no kind of behavior for a planet. No!”

Analyzing the differences in the arguments of both sides, it’s evident that planetary scientists are much more expansive in their definition of the Solar System’s planets than are astronomers. If they were to prevail in persuading the IAU to rescind its 2006 decision, there would immediately be upwards of 450 more objects that qualify as planets, with no distinction in essence between gas giant Jupiter and tiny, icy Pluto and its fellow plutinos.

Astronomers have a vested interest in the taxonomy of cataloged space objects. They see a clear distinction between planets from Mercury to Neptune and those smaller objects further out in space. In the end, perhaps it’s a matter of classification. It seems unlikely that the IAU will revisit its definition anytime soon. And, are we really ready to include hundreds of other objects in orbit around our Sun as planets on an equal footing with Earth and Saturn? If so, studying for that grade school science exam on the planets becomes exponentially more difficult. If not, maybe we are ready to allow Pluto to be the leading dwarf planet in its new classification – until the next one comes into view.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image: Pluto, as captured by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft. (NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)