The Monterey Pop Festival, an unprecedented gathering of people and performers, many under the influence of LSD, helped create 1967’s Summer of Love, and was instrumental in how millions experience live music today.

◊

“The Summer of Love” was an attention-grabbing headline thought up by two hippie journalists to describe what they saw happening in San Francisco in 1967. The term now stands for a brief, watershed moment when American history, pop culture, and modern media were joined together for the first time.

That summer of ’67 offered a brief respite from a conservative and corporate social order responsible for the 20 previous years of Cold War regimentation and paranoia, and an escalating hot war in Vietnam. Crucial for what was to come, a countercultural refuge was created, not by religious crusaders, popular politicians, or esteemed artists, but by a handful of young musicians and publicists, mostly Californians, mainly unknown to adults over the age of 30.

Stream 1967: Summer of Love on MagellanTV now.

These organizers benefited from a climate of ideas unique to the Golden State’s traditional bohemian values of independence, free expression, and a desire for experimentation and innovation. In doing so, they created a performance space in a small oceanside town that not only launched the careers of artists who changed the trajectory of what was possible in popular music, but also developed ideas of collective action that both powered the ongoing peace movement and provided a template for how live music is enjoyed by millions today.

LSD Hits the Scene

Strangely enough, it all began in 1966, when California made possession of LSD a crime. The powerful hallucinogen, synthesized in Switzerland in 1938, was by the late 1950s increasingly used in both legitimate psychological treatments, and as a possible secret anti-personnel weapon in army experiments. By 1962, the LSD genie escaped the research bottle when medical insiders were themselves transformed by undergoing what was called the psychedelic experience. Some began distributing the drug, most notably in California, to curious outsiders.

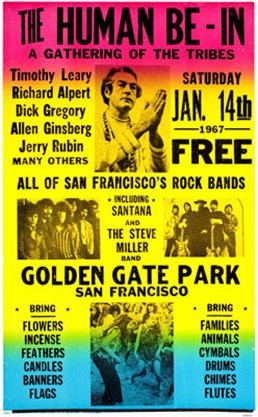

Soon, amateur chemists were producing the drug wholesale, making batches that were then sold as low-cost “hits” or, in many cases, dispensed for free for increasingly popular performance “happenings” in the Bay Area. By 1966, California authorities had seen enough. In October that year, on the day the drug was legally forbidden, a small and peaceful political gathering, called the Human Be-In, was held in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco.

Poster for San Francisco’s Human Be-In, January 1967 (Source: https://thehumanbein.com/human-bein-1967)

A mix of music and poetry, it rallied a sense of an alternative community that led to a larger, far more organized event in January 1967. The second Be-In was held in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, a free concert by local musicians before an estimated crowd of 30,000. A counterculture was born.

Down the coast in Los Angeles, two young promoters were planning a music festival of innovative pop music acts like the Beach Boys and Simon and Garfunkel for a June weekend at the fairgrounds site of the venerable Monterey Jazz Festival. The two contacted singer/songwriter John Phillips and record producer Lou Adler. Phillips and his folk band the Mamas & the Papas had recently charted enormous pop hits with “Monday, Monday” and “California Dreamin'.” The latter gave a quasi-mystical sound to a musical subject already popularized by the Beach Boys – the Golden State as a radiant destination for a new legion of seekers.

Phillips had noted the magnetic draw of the Be-In, 100 miles north of Monterey, and resolved to create an event that would bring dozens of performers to a live audience of tens of thousands, something far beyond the scale of the town’s laid-back jazz fest.

There was a big difference between California musicians who, like Phillips, lived and worked in Los Angeles and those, such as the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead, headquartered in San Francisco. Los Angeles, with its recording studios and session musicians, was all about the serious business of popular music. In San Francisco, the players were rougher, rowdier. They were steeped in folk music and the blues, and fond of loud, live performances characterized by hypnotic light shows and improvised ensemble playing that aptly mimicked the flowing, un-cohesive nature of an acid trip.

The San Francisco contingent liked the idea of a festival, with just one catch: They would perform only if all the musicians would play for free, with proceeds going to designated charities. Phillips and Adler agreed, and now had seven weeks to draw the event together. Helping them was the Beatles’ former manager, Derek Taylor, who added a few British imports to the lineup.

“I was just surrounded by this unbelievably extraordinary [acid rock] music. It seemed like a tidal wave. I felt engulfed by it.” —Pete Townshend (The Who)

To promote the event, Phillips wrote the treacly ballad “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair).” Recorded by Phillips’s friend Scott McKenzie, it was a nationwide hit that May. ABC television paid $200,000 (the equivalent of over $1,600,000 in 2022) to air event performances filmed by a crew equipped with the latest sync-sound cameras and headed by the in-demand documentary cameraman D.A. Pennebaker. Sound engineers created an amplifier design for the outdoor amphitheater that offered unprecedented volume and clarity for the performers and audience. Literally nothing like it had ever been heard before.

Joplin and Hendrix Become Overnight Sensations

Starting Friday night, June 16, the program unfolded in afternoon and evening sessions, each requiring a separate ticket to the 7,000-seat venue. The music, however, could be heard by thousands more on the festival grounds.

If the music was mostly free, so, apparently, was the LSD. Thousands of hits were synthesized, then given away, by the Grateful Dead’s chief sound engineer, Owsley Stanley. In anticipation of people undergoing a psychedelic experience for the first time, a large tent was set aside with a staff to help sufferers on “bad trips.” Remarkably, the festival suffered no deaths or overdoses, and very few arrests. Monterey police were in force on-site, and turned a blind eye to widespread marijuana smoking. The overwhelmingly engaged and peaceful crowd has been estimated to have been somewhere between 25,000 and 90,000 people.

The highlight of the first night was not the superstar folk duo Simon and Garfunkel, but a set of supercharged psychedelic British blues offered by Eric Burden and the Animals. Monterey was where one brand of pop music officially ended and another one began. An immediate divide appeared separating these acts from popular groups, such as the Beach Boys and Sonny & Cher, whose music sounded immediately dated.

Each band was given 35 minutes, with eight bands on each program. A total of 31 acts performed over the course of three days. The breakout set that Saturday was by Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company. A blues shouter from Port Arthur, Texas, the 24-year-old Joplin was already a San Francisco celebrity, having performed at the January Be-In.

Though a management disagreement prevented the film crew from covering her set, Joplin’s performance was so incendiary – no singer equaled her scorching vocal delivery – the band returned the following night, at Joplin’s insistence, to be filmed for posterity.

Something was definitely in the air that final night of the festival. Taking the stage shortly after Joplin, London-based rockers The Who made what was effectively their U.S. debut with a thunderous set that ended with the band’s brand of utter stage mayhem. Under howling feedback, guitarist Pete Townsend slammed his instrument into pieces as Keith Moon kicked his drum set across the stage while setting off smoke bombs.

“It took me a long time to understand that [The Who] was ‘theater,’ rock theater. I’d never been exposed to it before.” —Michelle Phillips (The Mamas & The Papas)

Many confused the antics with the beginning of a riot. Townshend had gone all-out, knowing The Who would be upstaged by another London-based performer, all but unknown in the United States, coming up next – Jimi Hendrix. The two London headliners had flipped a coin to see which one would go on first. A relieved Townsend won the toss.

Michelle Phillips of the Mamas & the Papas performs at the Monterey Pop Festival, 1967. (Source: Wikimedia/photographer unknown)

And, after a short blues set by the Grateful Dead, the Jimi Hendrix Experience indeed stole the show. With drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Noel Redding, the guitarist’s inventive, feedback-heavy playing was just part of an uninhibited performance that definitely added an element of sex to the prevailing atmosphere of drugs and rock ’n’ roll.

“If you sat in the audience for that show, you were devastated, man.” —David Crosby (The Byrds)

Hendrix ended his set with what might be the iconic moment in rock history. In a confident bid to upstage The Who, he told the audience he was going to sacrifice something he dearly loved, just for them. Kneeling before his shrieking Fender Stratocaster, laid flat on the stage, he doused it with lighter fluid and set it on fire.

Jimi Hendrix inflames the crowd at the Monterey Pop Festival with his incendiary theatrics. (Source: GIPHY)

Publicity Kills the San Francisco Hippie Scene

What could possibly follow that? Scott McKenzie, up next, sang “San Francisco” and the Mamas & the Papas followed with an indifferent, anticlimactic set that ended the event. The first and last Monterey Pop Festival was history.

When he saw the footage of Hendrix’s onstage antics, a horrified ABC president released the filmmakers from any broadcast obligation (“Not on my network,” he vowed). Pennebaker edited the film into a feature-length documentary for theatrical release. In the coming months, the documentary music film Monterey Pop was seen by millions.

McKenzie’s hit single, and the overwhelmingly positive publicity surrounding the festival, brought an estimated 100,000 young people to the streets of San Francisco that summer. The newcomers quickly overwhelmed the local bohemian subculture. Most of the musicians and artists who created the scene years earlier left town.

“When the media found us, that was the end of it. [The Haight-Ashbury scene] basically couldn’t continue to happen.” —Bob Weir (Grateful Dead)

In retrospect, we can see that the Monterey Pop Festival did not just launch a new wave of loud, fast, and wildly expressive popular music. Directly inspiring the Woodstock music festival held in upstate New York less than two years later, it debuted a new way for people to experience live performances. Many of the same acts that played in Monterey performed there for an estimated crowd of 500,000.

Sadly, 1969’s Woodstock Music and Art Fair in Bethel, New York, would be a last hurrah. Deadly violence four months later at an outdoor festival organized by the Rolling Stones at an Altamont, California, racetrack ended whatever sense of optimism remained in ’60s hippie culture. Tragically, both Joplin and Hendrix died of drug-related causes within a month of each other in late 1970. An era barely begun had ended.

But outdoor festivals did not go away, and there are hundreds of open-air music events, such as California’s Coachella and Tennessee’s Bonnaroo, held over spring and summer weekends in the United States today. Tens of thousands are drawn into a communal atmosphere that reaches back to the Summer of Love. Pop music and film were linked forever after by Pennebaker’s groundbreaking movie, and even more so by Michael Wadleigh’s film Woodstock a few years later. And, thanks to licensing agreements, the Monterey International Pop Festival Foundation was still dispersing money in 2017 to musical charities around the Bay Area.

Ω

Contributing writer Joe Gioia is the author of The Guitar and the New World, a social history of American roots music. He lives in Livingston, Montana.

Title image: Janis Joplin in performance (Source: Wikimedia Commons/ABC TV)