World’s Fairs captured the public’s attention for generations thanks to the events’ fascinating nature – but the novelty seems to have worn off.

◊

World’s Fairs of the past brought together great minds and inventions that the average person would never encounter otherwise. At one time, information traveled past the communities where it originated through published books and word of mouth. That was revolutionized in the Age of the Steam Engine with the advances wrought by railroads, steam-powered boats, and eventually the automobile. In today’s age of community libraries, free museums and, of course, the Internet, information is almost overwhelmingly accessible.

Over 100 World’s Fairs, also known as international expositions or exhibitions, took place over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries. These highly orchestrated festivals gathered people from all over the world to share their most recent inventions in manufacturing, design, urban planning, and chemistry. In recent decades, they have become less frequent due to increasingly strict regulations from the Bureau International de Expositions (BIE) and a waning public interest in them. The rise and fall of World’s Fairs happened over the course of just a few centuries and are more complicated than you might think.

The City of Lights lit up for the Exposition Universelle of 1900. Get the full story in this enlightening MagellanTV documentary.

Early Fascination with Fairs

While multinational expositions took hold of the public’s attention in the mid-19th century, fairs and large cultural events have been a staple of human history. The word “fair” is derived from the Latin term feria, which alludes to holy days observed by taking off work. Fairs in Medieval Europe usually lasted three days to make time for vigils, feasts, and a little bit of rest.

Once Renaissance ideals gained traction, powerful families began investing in secular institutions that furthered science and art, instead of just sponsoring local celebrations for religious holidays. Sites of cultural investment became more permanent and offered people from a specific community and others visiting from far away the opportunity to engage with artifacts year round.

The Creation of Cultural Hubs

Museums and cultural expositions grew in popularity alongside the rise of industrialized economies. The factory system and advances in energy production transformed manufacturing, making it possible for the growing middle and upper classes, who had more disposable income, to become patrons of museums and cultural institutions. Increased private patronage breathed new life into both sacred and secular cultural institutions.

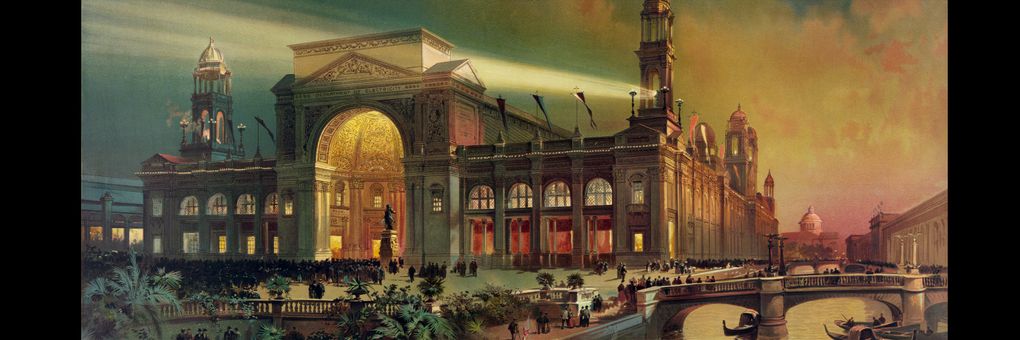

In England, in 1754, a group of like-minded men called themselves the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. They were united by a common goal to further the development of creative ideas with the aim of helping the public. In 1760, the organization hosted the first exhibition of contemporary art. Funds were pooled to offer a prize. Participants showcasing their work were motivated to try new techniques and to present their best possible work.

Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Adelphi (Credit: Thomas Rowlandson et al., via Wikimedia Commons)

Agricultural Fairs in North America

Many American businessmen and traders, traveling frequently between the U.S. and Europe, would identify ideas and practices to bring back to North America. On one of his frequent trips abroad, a well-traveled agriculturalist named Elkanah Watson noted the differences between American husbandry and the methods used in Europe. After bringing over a few Merino sheep to his farm in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, Watson invited people to see the animals and learn about the unique type of wool they produced. Records indicate around 3,000–4,000 people flocked to his farm.

Watson established the first agricultural society in the U.S. in 1810, creating an educational community specifically for farmers to support their apparent interest in keeping up with the latest industry practices. As had been done at some art fairs in the past, Watson suggested awarding prizes for premium inventions, practices, and livestock to encourage new ideas and quality work. These gatherings created a platform for experts to discuss innovation in general.

The Golden Age of World’s Fairs

Between 1851 and 1916, the popularity and frequency of World’s Fairs peaked. Some, however, were of greater historical interest than others. Here are a few of the most significant expositions:

London, 1851

“The Great Exhibition,” held in 1851 in London’s Hyde Park, laid the foundation for World’s Fairs. The event was pioneered by Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert, who was head of the Society of Arts at the time. As the British Empire flourished in the age of industrialism, he wanted to elevate the status of industrial design to the same level as fine art. Albert worked alongside architects, urban planners, and arts patrons to create visually stunning objects and exhibitions to exemplify the intersection of art and design in an industrialized economy.

The Great Exhibition in 1851 (Credit: J. McNeven, via Wikimedia Commons)

Mostly housed within the Crystal Palace, a glass and iron structure complete with indoor gardens, fountains, and sculpture that was built expressly for the event, the Great Exhibition was a neutral coming together of nations, showcasing the best of international design, engineering, and art. The sheer excitement surrounding the construction of the Crystal Palace drew an estimated 6 million visitors to see the 100,000 exhibits.

Philadelphia, 1876

The World’s Fair was held in Philadelphia in 1876 to commemorate the centennial of the founding of the United States. This event was a monumental financial investment and was designed to encourage national pride by showcasing the best in American ingenuity. From the telephone to the world’s largest steam engine, 10 million people gawked at both the technological advances presented in this exposition.

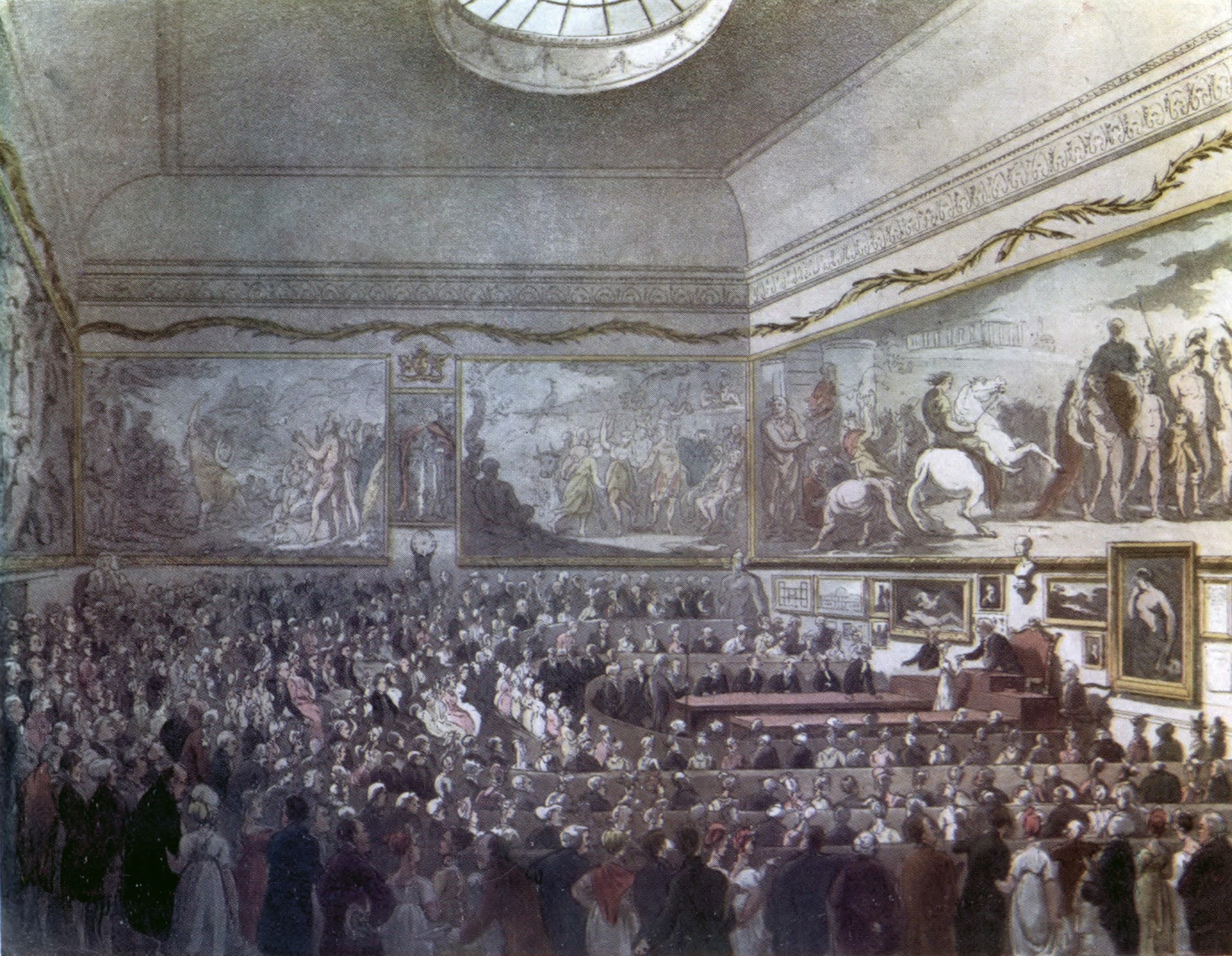

Paris, 1889

The 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris coincided with the hundred-year anniversary of the start of the French Revolution. While initial plans featured a 300-foot tall guillotine, the idea was axed in favor of Gustave Eiffel’s iconic tower. Although several nations refrained from participating for fear of associating themselves with a nation celebrating a democratic revolution, France gained economically and politically by hosting the event.

Some exhibitions at the fair paid homage to the nation’s colonial power. In the Javanese Village, for example, the French had imported several structures directly from Java as well as indigenous dancers for performances. A French architect recreated a pagoda reminiscent of the temples of Angkor Wat to celebrate the breadth of cultures under the French empire.

Pagoda of Ankor, Paris Exhibition. Paris, France, 1889 (Source: Library of Congress)

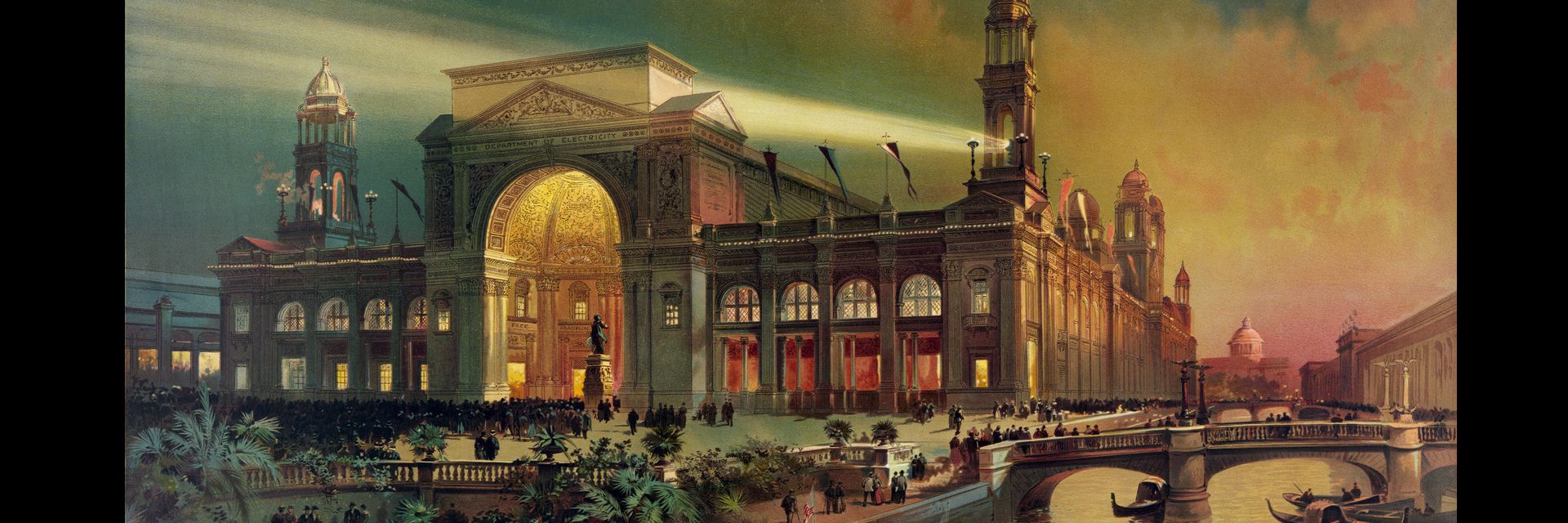

Chicago, 1893

The Columbian Exposition saw the city of Chicago transform into the “White City,” a nickname inspired by the beaux-arts and neoclassical style of white exteriors that brought the city to life. In a triumphant display of technological advancement, 160,000 light bulbs powered by George Westinghouse’s alternating current lit the streets. The fair also introduced the world to fun inventions such as the Ferris wheel, Juicy Fruit chewing gum, and brownies. Although many buildings were erected on a temporary basis, the huge investment in beautifying Chicago and creating infrastructure to support 150,000 daily visitors brought the city back to life following the devastating Great Fire of Chicago in 1871.

The first recognized serial killer in the United States, H.H. Holmes, relied on the bustle and excitement around Chicago’s Columbian Exhibition to draw attention away from his “Murder Castle,” which was most certainly not a part of the city’s beautification efforts.

Paris, 1900

The 1900 World Expo in Paris built upon the pre-existing infrastructure from earlier World’s Fairs hosted in the City of Lights. The capital city positioned itself as a cultural hub in 1900 by hosting the Olympic Games as well. Fortunately, a priority of the Expo was showcasing short-distance transit solutions. The city’s first Metro line carried passengers across the city, and moving walkways facilitated quick walks from one exhibition to the next. This World’s Fair gave nations from all around the world a platform to showcase cutting-edge inventions, cultural advancements, and social developments. However, many communities were under colonial rule and were presented as exotic oddities on display, rather than as intellectual contemporaries.

Eiffel Tower under construction

Among the more notable exhibitions was the Exhibition of American Negroes, a pavilion led by internationally acclaimed sociologist W.E.B. Dubois. The display presented patents awarded to Black inventors, books by Black scholars, and images of Black communities that challenged stereotypes of African Americans being under-educated and living in squalor. While the exhibition was one of the first of its kind to celebrate the contributions of African Americans on an international stage, it received little attention.

San Francisco, 1915

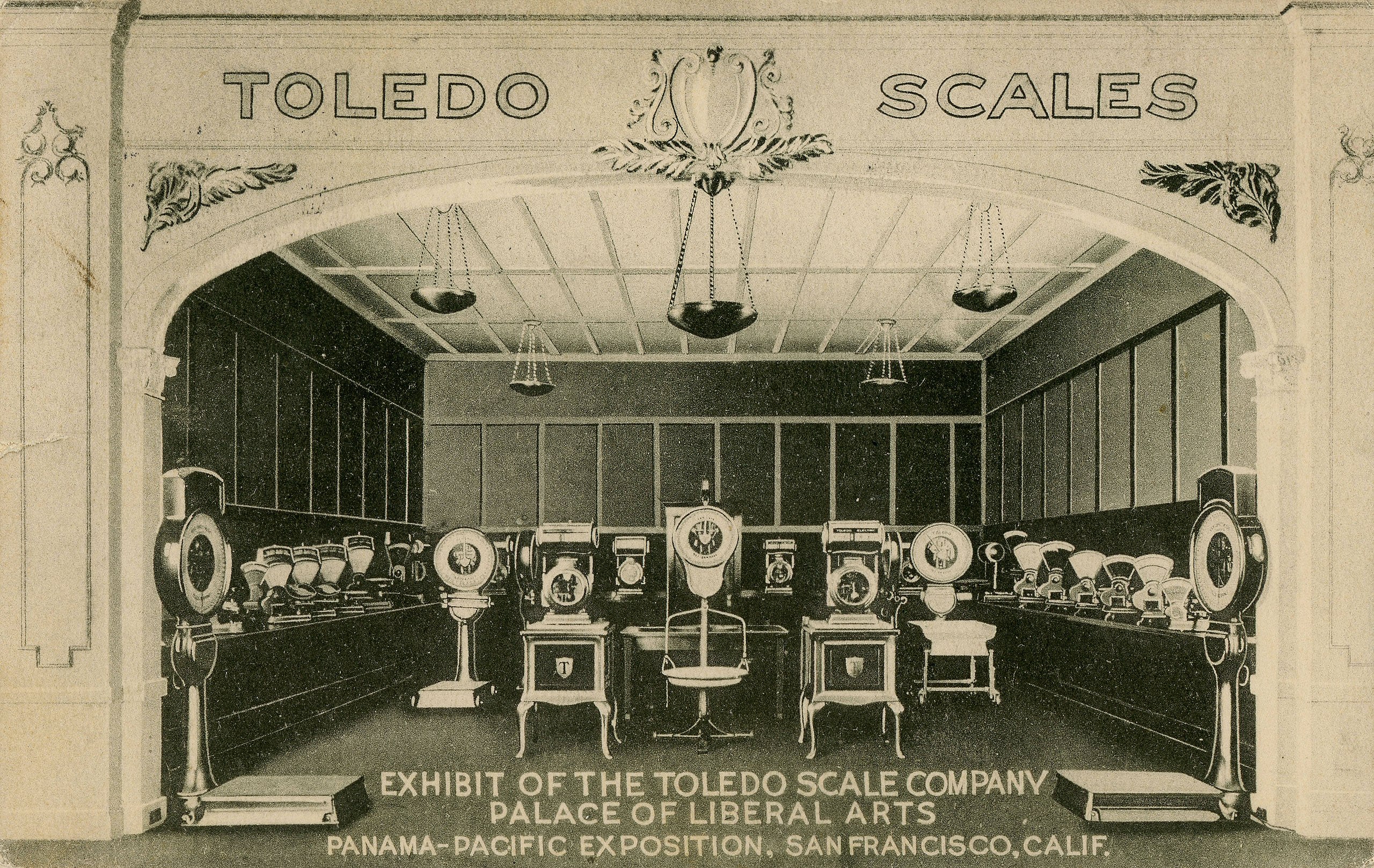

The Panama Pacific International Exposition celebrated the completion of the Panama Canal, which created a revolutionary passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans to facilitate international trade. This fair spanned 600 acres across Northern California’s coastal landscapes and marshlands. During the event, engineers demonstrated a transcontinental phone call and wireless telegraph communications. Eighteen million people passed through the area, taking part in one of the last World’s Fairs before the world wars would forever alter the dynamics of international gatherings.

Exhibit of the Toledo Scale Company, San Francisco, CA (Credit: Toledo-Lucas County Public Library, via Wikimedia Commons)

Losing Steam in the 20th Century

From their beginning up until 1915, World’s Fairs had been held every three and a half years on average. A 13-year gap between expos took place in the early 20th century for what are perhaps obvious reasons during World War I. World’s Fairs were revived in Barcelona in 1929, but a much smaller number of visitors than usual – only about 6 million people – attended.

Shadowed by the Great Depression, in 1933, the World’s Fair returned to Chicago. Rather than depending upon government funding, however, this event was backed by private investors and corporations that used their participation for marketing. This set a precedent wherein World’s Fair attendees were seen as captive audiences for corporations’ marketing agendas – a striking shift from the national sponsorships of decades past.

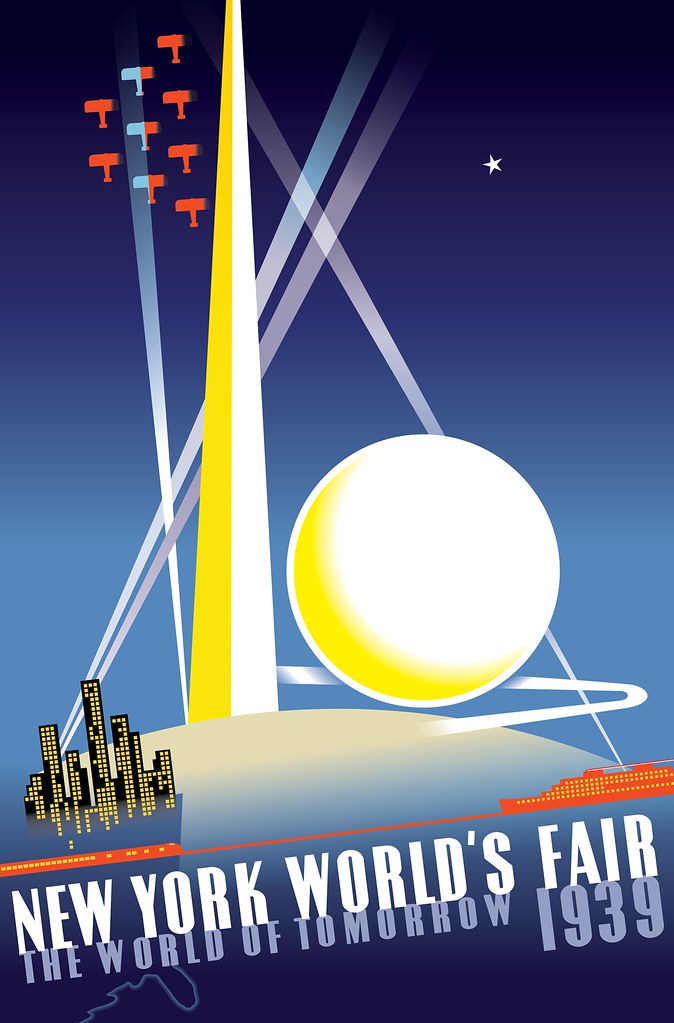

(Credit: Joseph Binder, via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1939, New York City hosted an exposition on the eve of World War II portentously titled, “The World of Tomorrow.” Even though this fair saw the unveiling of television, color photography, air conditioning, nylon, and fluorescent lighting – all inventions that have fundamentally changed day-to-day life – it was soon eclipsed by the horrors of the blitzkrieg and the Holocaust. The Bureau International de Expositions’ plans for upcoming fairs, including plans to host the first international expo in Asia in 1940, were postponed due to the outbreak of another world war.

World’s Fairs after the World Wars

After a 10-year pause, the World’s Fair returned, this time in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. The attendance for “The Festival of Peace” was dismal, with only 250,000 visitors. But highly successful and well-attended fairs backed by the BIE in Brussels (1958), Seattle (1962), and Montreal (1967) breathed new life into the events. (The 1964 New York World’s Fair, which was not supported by the BIE, was also an enormous success.)

With over 64 million visitors, the Osaka International Expo (1970) was the most successful World’s Fair in history, by attendance. The event was titled “Progress and Harmony for Mankind” and aimed to create neutral ground for powers from both the East and West to come together. At the time, Cold War tensions between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. still dominated geopolitics, and many attended the event to compare the relative ingenuity of these rival nations. Japan used the event to reestablish itself on the world stage, but corporate sponsorship combined with international political intrigue to undermine the sense of openness and generosity that once defined World’s Fairs.

The Fuji Pavillion at the 1970 Expo in Osaka (Credit: kouij OOTA, via Wikimedia Commons)

World’s Fairs in the 21st Century

After Osaka, the BIE imposed more stringent criteria for international expos, and the steep cost of hosting the exhibitions became prohibitive for many cities. Meanwhile, specific industries and professional associations began hosting their own highly specialized trade shows to continue with the tradition of showcasing technological advancements – directly competing for the World’s Fairs’ audience. To maintain relevance, World’s Fairs began focusing more narrowly around particular themes instead of appealing to a global community in the name of tradition.

World’s Fairs once preached utopianism through industrialization, but now they feature proposed solutions to the crises spurred by over-industrialization. The 2015 World’s Fair in Milan was themed “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life,” and the 2020 expo in Dubai focused on“Connecting Minds, Creating the Future: Opportunity, Mobility and Sustainability.” The next World’s Fair will take place once again in Osaka. Scheduled for April 13 and October 13, 2025, the theme will be “Designing Future Society for Our Lives.”

While World’s Fairs are still staged, they don’t have the same draw they once had. Although they have their purposes, World’s Fairs haven’t regained the hold they had before the political and economic disasters of the 20th century. Corporations pay a premium for access to the crowds at expos today – for some, expos are no longer about idea-sharing but rather about gaining exposure for their brands. The true legacy of World’s Fairs continues on in the spirit of knowledge-sharing in industry-specific expos, cultural exchange programs, and worldwide educational communities.

Still, remnants of the World’s Fairs define skylines worldwide. Be it the iconic silhouette of Seattle’s Space Needle or the street layout of Chicago, the legacy of bygone fairs is etched into the design of major cities. World’s Fairs will forever be entangled with the history of some of humankind’s most pivotal inventions, but their ironic transition from harbinger of the future to warning of the side effects of those creations is not lost on the paying public.

Ω

Daisy Dow is a contributing writer for MagellanTV. Originally from Georgia, she went to college to study philosophy and studio art. She now works in Chicago as a freelance writer.

Title Image: Electrical Building, World Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1892 (Credit: Charles S. Graham, via Wikimedia Commons)