Olympic Games in the spirit of peace could not keep these athletes from going to war.

◊

While “manpower” is perhaps not the most applicable term these days, every combatant country has contributed a large human element to its role in war, and that does not seem likely to change any time soon. Historically, professional soldiers and other military personnel have represented only a small percentage of combatant forces. The rest, volunteers and conscripts, come from all walks of life, amateur and professional athletes among them.

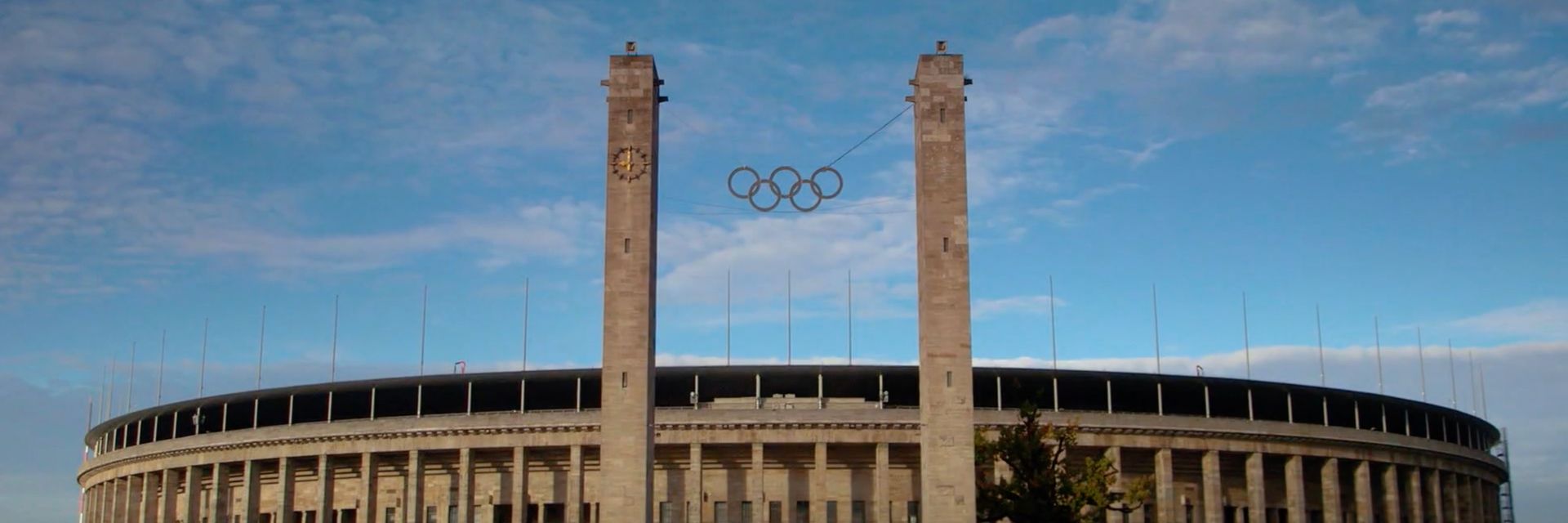

The story of how the 1936 Olympics, and particularly the Summer Games in Berlin, became a politically charged spectacle is well known. It does not take away from the outstanding level of competition. Among medal winners were military veterans and those who would shortly enter the service of their respective countries in World War II. Many other athletes who participated in the games but did not place also served, and even died, during World War II. A number of competitors, mostly in the equestrian and shooting events, were active military officers. There are even a few connections to the First World War in the personalities of the Berlin Summer Games, including the initially reluctant host, Adolf Hitler.

The eyes of the world were on the spectacle. A growing new wave of journalists, benefiting from increased technological access, brought the Olympics to a global audience, hungry for the news of the competition. Politicians and scholars watched the developing controversies arising from Germany’s handling of the games, when host city Berlin went from being the least volatile of the finalist cities to the capital of the increasingly dangerous Nazi regime.

Watch this MagellanTV documentary for a deep dive into the 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics.

The Competitors

Politics and media were nothing new to the Olympians who arrived in the summer of 1936 to compete in any of 129 events, covering 19 sports and six other demonstration matchups. Most were seasoned athletes who had competed at college and amateur meets many times before, including previous Olympic games. They recognized the value to their sports and themselves of exhibiting good public relations behavior. Even in 1936, humble and gracious superstar Jesse Owens, from rural Alabama, had mastered the art of celebrity engagement before setting foot in Germany.

Discrimination and vilification were present at the games, with Jewish participants (those that were allowed to compete) and Americans of African descent being targeted. For example, Wolfgang Fürstner – not a competitor but an Olympic official – was a Heer (army) captain who served in World War I. He was assigned to build the Olympic Village and became its commander, a task he performed well and without reprimand. That is, until it was discovered he had Jewish ancestry. Fürstner was then demoted to vice-commander with the invented explanation that he did not “act with the necessary energy” to prevent damage when 370,000 visitors toured the village before the Games commenced.

No doubt the competitors were aware of the discriminatory atmosphere, and some were uncomfortable with it. Being athletes, however, they were there to compete and win medals, with injury and bad luck being their principal concerns. At the Olympic level, most were capable of extreme focus, shutting out all the noise and controversy. Many did discuss the issues among themselves or with others at the time. But most of those with strong feelings about the political atmosphere either stayed home or expressed their opinions later. Those primary problems they faced were largely out of their control. After all, injuries happen, and bad luck, including incidents of bad officiating, cheating, and doping, are always part of sports competitions.

Sydney Charles Wooderson was a U.K. runner known for his diminutive size. In Berlin, he suffered an ankle injury that kept him from qualifying for the finals in the 1,500-meter event. When the war came, his poor eyesight excluded him from active duty, so Sydney joined the Royal Pioneer Corps and acted as a firefighter during the Blitz. Later in the war, he joined the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers in the radar service. In 1944, he contracted rheumatic fever, and doctors did not think he would ever be able to run again, But he did.

Nikolaus Anton “Toni” Merkens was a well-known German racing cyclist when he took the gold medal in the men’s 1,000-meter match sprint event. In the first race of the final, he interfered with Arie van Vliet of the Netherlands, but the interference was not called by the officials. When the Netherlands team protested, Merkens was not disqualified, but was instead fined 100 marks. He was drafted into the German army in 1942 and took a shell splinter in the chest while fighting the Soviets on the Eastern Front. He died in a hospital of meningitis.

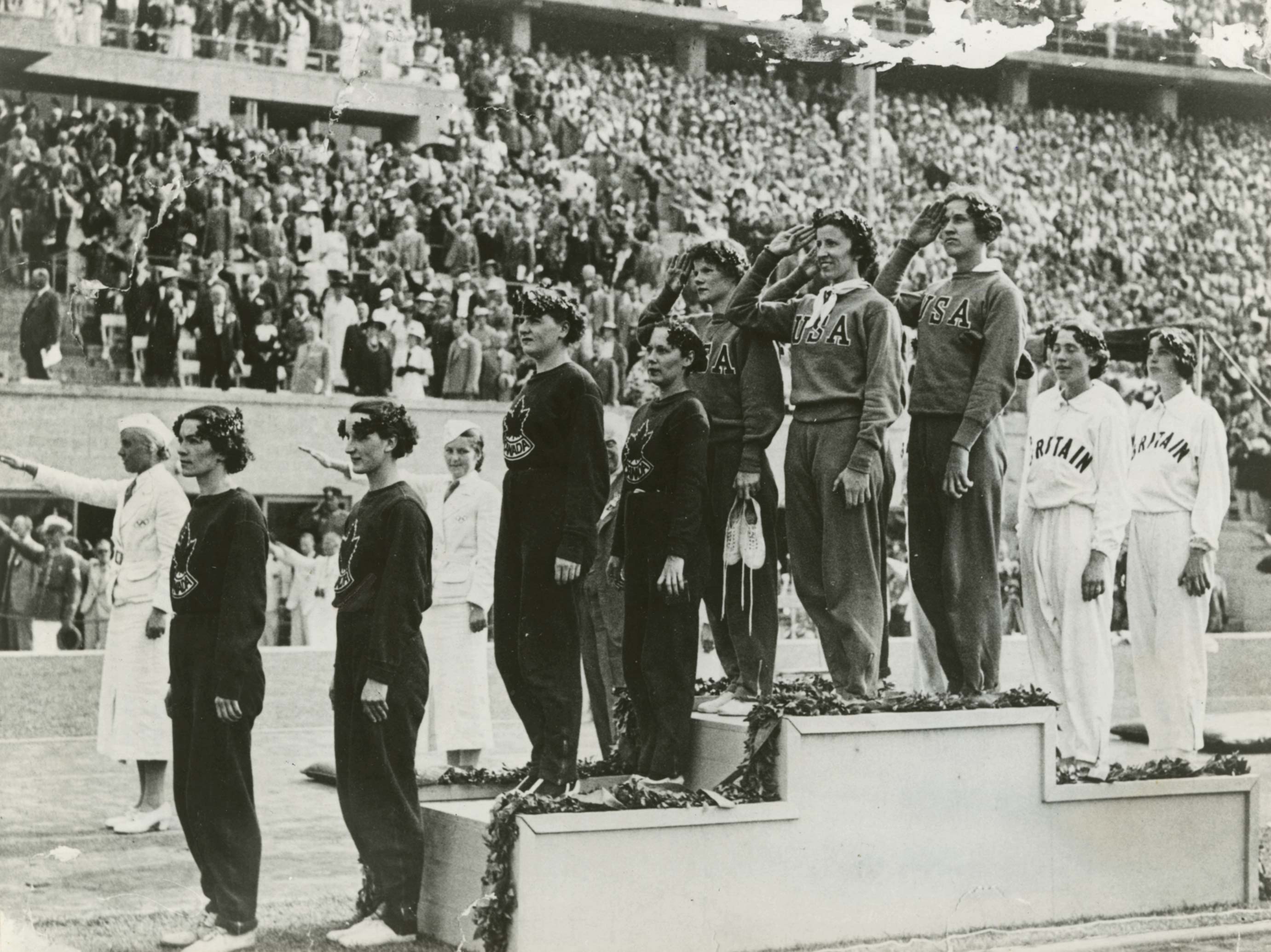

Canada (Bronze), American (Gold), and British (Silver) women’s 4x100 meter relay teams accepting medals. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Canada (Bronze), American (Gold), and British (Silver) women’s 4x100 meter relay teams accepting medals. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Known as the “Fulton Flash,” Helen Stephens was a popular figure from the Games when she returned to her native Missouri. She had been a member of the U.S. women’s 4 x 100 relay team, which won the gold medal against the heavily favored Germans in the event. Back in her hometown of Fulton, she operated some professional women’s sports teams. In 1941, Helen became a “Rosie the Riveter,” when she worked at the Curtiss-Wright airplane factory in St. Louis. Later in the war, she worked for the Army Audit Branch of the General Accounting Office.

U. S. government official poster to recruit women to work in war industries during WWII (Credit: J. Howard Miller, restored by Adam Cuerden, via Wikimedia Commons)

U. S. government official poster to recruit women to work in war industries during WWII (Credit: J. Howard Miller, restored by Adam Cuerden, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Jesse Owens Connection

The story of Jesse Owens and his record four gold medals is the best-known story of the 1936 Olympic Games. Having already established many track and field records, his performance in Berlin was much anticipated and did not disappoint. Returning to the U.S., racial discrimination and other factors led to him struggling to survive financially, even as he remained a celebrity. Owens did not serve in the military in World War II, but some with whom he started long-term friendships at the ’36 Games did.

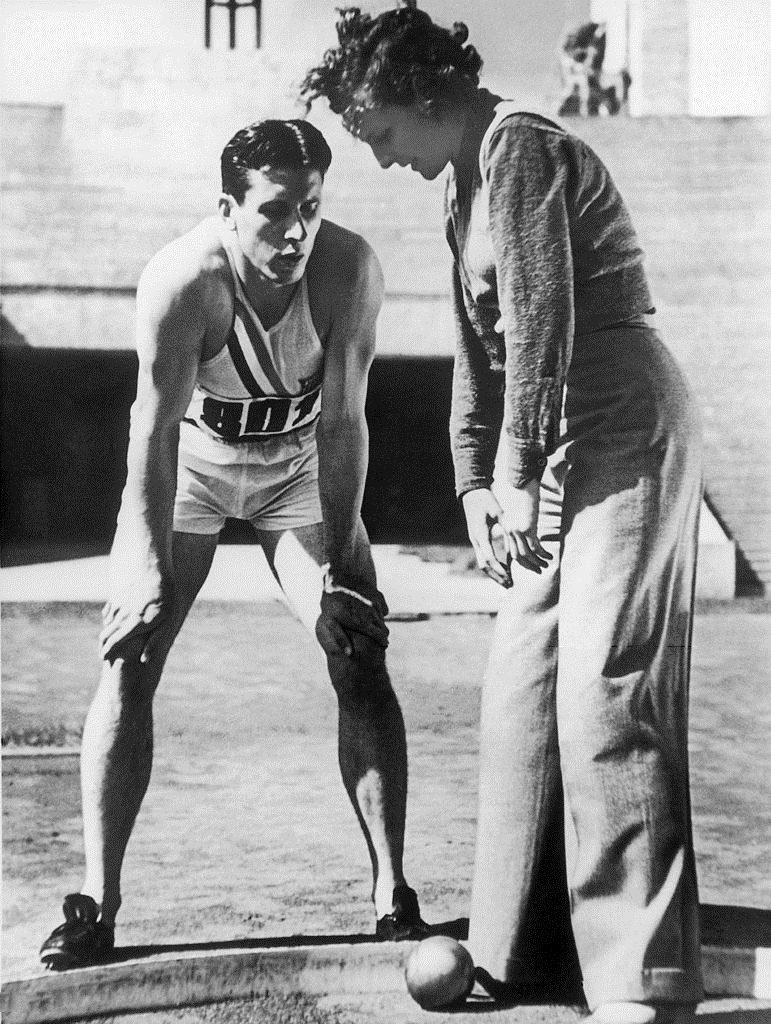

One of them was Carl Ludwig “Luz” Long, a German competitor in the long jump. He studied law at the University of Leipzig and became a practicing attorney. And, as a member of the Leipziger Sports Club, he won the German championship six times in the 1930s. While the legend that he gave Jesse Owens a tip to help him beat Long (by 10 centimeters) in the long jump finals isn’t true, the two did become fast friends after Owens took the gold and Long the silver. The friendship continued after the Games ended. Long was drafted into the Wehrmacht and served as an Obergefreiter (enlisted) soldier during the Allied invasion of Sicily. He was wounded on July 10, 1943, in the battle for the Biscari-Santo Pietro airfield and died four days later in a British military hospital at Acate. He is buried in the German war cemetery at Motta Sant’ Anastasia. In a well-publicized postwar visit to Berlin, Owens met Long’s son, Kai-Heinrich Long.

Luz Long and Jesse Owens walk arm-in-arm at the Berlin Olympics after competing against each other. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Luz Long and Jesse Owens walk arm-in-arm at the Berlin Olympics after competing against each other. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Ralph Metcalf of Chicago took the silver medal, behind Owens, in the 100-meter race. He, Owens, and two other Americans won the gold medal in the 1 x 100-meter relay, beating Italy and Germany. Competitors on the track, Metcalf and Owens were lifelong friends. Metcalf joined the U.S. Army Transportation Corps in World War II and rose to the rank of first lieutenant in the European Theater. He was awarded the French Legion of Merit award for service on the Red Ball Express.

Olympic Pride, American Prejudice is a 2016 documentary by Deborah Riley Draper that deals with the discrimination against Black 1936 Olympic athletes at home. Included in the film is high jump gold medalist Cornelius Johnson, who joined the U.S. Merchant Marine in 1945.

Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympic Movie Stars

One of the best-remembered aspects of the Berlin Games was the production of Leni Riefenstahl’s film Olympia. The widely studied documentary, a masterpiece of propaganda, is the most complete visual document of the Games. Riefenstahl was everywhere with her cameras looking for the best subjects for her film. By her own account, she also invited at least one American into her bed, Glenn Morris.

Morris was a 24-year-old Colorado farm boy, Denver used car salesman, and Colorado State University star athlete who won the gold medal in the decathlon. He also reached celebrity status during the games and caught the eye of Riefenstahl, who featured him in various shots using her innovative camera techniques. During WWII, Morris was a commissioned U.S. Navy officer, commanding amphibious landing craft in the Pacific Theater. However, he suffered from psychological trauma issues and was committed to a naval hospital for several months. After the war, he drifted around the San Francisco Bay area, seemingly not the same man he had been as the pre-war Olympic champion. Friends wondered if his affair with Riefenstahl contributed to his melancholy.

American decathlon gold medalist Glenn Morris and filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl at Berlin Olympic Stadium, August 1936. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

American decathlon gold medalist Glenn Morris and filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl at Berlin Olympic Stadium, August 1936. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Another American who Riefenstahl’s camera favored was handsome blond diver Marshall Wayne, the gold medal winner in the 10-meter platform dive. He enlisted in the Army Air Corps (later AAF) and was commanding officer of the 7th Photo Reconnaissance Group based in Mt. Farm, England. In 1945, Colonel Wayne parachuted out of his damaged plane over Italy and landed in a tree, injuring his leg. He was taken in by an Italian family and later smuggled out of Italy, returning to England.

Sports television made its debut when German cameramen covered the events at Olympic Stadium with giant cameras on a closed-circuit system that fed the Olympic Village and other venues.

Other Notable Olympians Who Fought in WWII

There were 591 known 1936 Olympic athletes killed in action in World War II. The list of them included athletes from many of the participating countries and from all theaters of the war.

Canadian John Wilfrid Loaring of Winnipeg won the silver medal in the 400-meter hurdles as the youngest competitor in the event. Loaring enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve when World War II began. He served as a radar officer on Royal Navy ships and was part of a destroyer rescue team that saved passengers of a torpedoed ocean liner. When the light cruiser HMS Fiji, on which he was serving, was torpedoed and sunk by German submarines off Crete, Loaring survived by swimming among the ship’s debris until he was rescued.

John Edward “Jack” Lovelock was a popular New Zealand athlete who was captain of the country’s Olympic team. He was the gold medalist in the 1500-meter race. Lovelock had previously obtained a degree in medicine and was a major in the Royal Army Medical Corps in World War II.

Alfred Schwarzmann was already in the Wehrmacht when he competed in the 1936 Olympics for Germany. He won three gold and two bronze medals, adding to Germany’s overall domination. When the Germans invaded the Low Countries and France on May 10, 1940, Schwarzmann was one of the paratroopers dropped into the Netherlands. He helped take the key bridge at Moerdijk but was badly wounded in the action. He survived the war and competed again, winning a medal in the 1952 Olympics.

The gold medal in the modern pentathlon went to German Gotthard Handrick. Handrick’s post-Olympics military career was prolific. He was a Luftwaffe pilot in the Spanish Civil War, and, later, during World War II, he quickly rose through the ranks of Luftwaffe fliers, becoming Wing Commander of Fighter Wing 77 on the Eastern Front and then Fighter Wing 5 in Norway and Northern Russia. He received the German Cross in Gold. By the end of the war he was commanding a division in Austria.

Louis Zamperini and damage to his B-24 bomber “SuperMan” in the Pacific, 1943 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Louis Zamperini and damage to his B-24 bomber “SuperMan” in the Pacific, 1943 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Though he did not win a medal, Torrance, California’s Louis Zamperini, a long-distance runner, gained attention at the games when, lagging behind in the 5,000-meter race, he made up time with a 56-second final lap. In World War II, the 13th Air Force B-24 in which he was navigator was shot down while flying a mission in the Central Pacific. He and several other crewmen survived a long, isolated ordeal until picked up by the Japanese. Until liberated, he was an unwilling and defiant POW in a compound on the Japanese Home Islands. Zamperini’s inspiring story is told in the book and film Unbroken.

The 1936 Olympic Games saw men and women come together to represent their countries and elevate their own athletic excellence. A staggering number of new world records were established during the Berlin Summer Games in many sports. The competitors pushed themselves relentlessly. The challenges of athletics and war are very different, but it often takes men and women of determination and courage to excel at both.

Ω

Jay Wertz is an award-winning author, publisher, and filmmaker. He has written seven books, including four volumes in the War Stories: World War II Firsthand™ series. Other books include The Native American Experience; The Civil War Experience 1861–1865; and Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, co-authored with Edwin C. Bearss. He is the editor and a primary contributor to D-Day 75th Anniversary – A Millennials Guide and other works for Monroe Publications. He has been a columnist and online contributor for Civil War Times Illustrated, America’s Civil War, Aviation History, Armchair General, and America in WWII magazines. He is also the producer-director-writer of the documentary series Smithsonian’s Great Battles of the Civil War for The Learning Channel and Time-Life Video.