Black cats, broken mirrors, four-leaf clovers. Superstitions are all around us. Heck, you can’t even spill some salt without summoning bad luck. But why do we have these collective beliefs and rituals? To begin to understand, we’ll take a look at some of the most popular superstitions in America, today. Many people believe in them. Do you?

◊

Growing up in an Italian household, my childhood was filled with tales of the past. My grandparents shared stories of evil eye curses, strange deaths, and village jealousy. For me, superstition was not out of the ordinary. And I’m not alone. No matter where you’re from, you probably have a few superstitions of your own. Each culture, each country, and each time period comes with a set of weird behaviors and beliefs to promote good luck and to ward off misfortune.

But in a more secular and jaded time, do these superstitions maintain their hold? Strangely, yes. According to the MagellanTV documentary Superstitious Minds, the percentage of people who identify as superstitious has risen by almost a quarter in the past decade, with people under 30 most affected.

For a fascinating dive into this world of irrational behavior, check out MagellanTV's Superstitious Minds.

Superstitions Have No Age Limits

It’s not unusual to see children hold their breath as they pass by cemeteries, or for adults to play “lucky” numbers when they purchase a lottery ticket. Irrational behaviors and rituals surrounding superstitious beliefs know no boundaries. Superstition is all around us. And while such beliefs are not limited by age, it is striking to see how different generations follow different rules.

Millennials, for instance, tend to focus on superstitions that invite good luck. Crossing their fingers for good luck and believing in “beginners luck” are two of the most widely held beliefs in superstitious, millennial minds. Baby boomers, on the other hand, are more likely to concentrate on avoiding bad luck. They fear the number 13, black cats, and open umbrellas indoors. It’s even reported that boomers avoid stepping on the cracks of sidewalks. (After all, who wants to break their mother’s back?) Generation X follows its own assortment of quirky rules. You’re unlikely to find a Gen Xer walking under a ladder or breaking a mirror, but, when they do, watch out for the salt they might throw over their left shoulder.

Age isn’t the only factor when it comes to superstitious beliefs. Trends also vary by region, with the South being the most superstitious. Of the Southerners surveyed, 42.7% admitted to being superstitious. The Northeast was close behind, with 42.2% reported. The farther west you move, however, the fewer superstitions seem to follow. In the Midwest, 38.4% of those surveyed reported being superstitious, and the number drops to 37% in the West. Perhaps the behaviors are regional, or perhaps some people are simply more likely to admit to their beliefs. Besides, everyone has some superstition in them. In the memorable words of The Office’s Michael Scott, “I’m not superstitious, but I’m a little stitious.”

5 Popular Superstitions in the U.S.

Whether you find yourself a believer or not, there is a large population of people who let superstitions influence their actions. In fact, common behaviors today are rooted in past superstitions (like saying “bless you” after a sneeze, or constructing new buildings without a 13th floor). Don’t believe me? Here are five of the top superstitions in contemporary America.

1. How Do You Solve a Problem like “13”?

Throughout human history, the number 13 has crept up as an infamous number. But how did it get such a bad rep? The origin of unlucky 13 can be traced back through millenia to different civilizations. For example, 13 was deemed unlucky by the ancient Sumerians. When they developed their numerical system, 12 was deemed to be the most “perfect” number. But that wasn’t lucky for the number 13. Because it followed in 12’s shadow, people began to think of 13 as lacking and strange – even unlucky. This belief stuck and found its way into the New Testament in the form of Judas – the betrayer – who was the 13th guest to arrive at the Last Supper.

Scared of Friday the 13th? Maybe Friday isn’t the day you should be worried about. Some countries (like Greece and Spain) actually believe Tuesday the 13th is the unlucky day.

While some have turned the superstition on its head and consider 13 a lucky number, it’s more commonly still feared. In fact, it is estimated that one third of people believe that bad things happen on Friday the 13th. The belief is so common there’s even a word for people with this fear: Paraskevidekatriaphobia. (Try saying that three times in a row, or even once!) People avoid traveling on Friday the 13th, stop doing business, and even refrain from getting married or celebrating special events. According tothe MagellanTV documentary Superstitious Minds, it’s avoided so much that up to $2.4 billion a year is lost in the global economy. Is that just unlucky for the economy, or is it because people avoid business ventures and work on this day?

2. Who Spilled the Salt?

Has anyone you know ever spilled salt, only to pause what they’re doing and throw the salt over their shoulder? You know, to ward off bad luck? I know I have (which was particularly inconvenient during my stint as a waitress). And I’ve seen many people do this, automatically without knowing why.

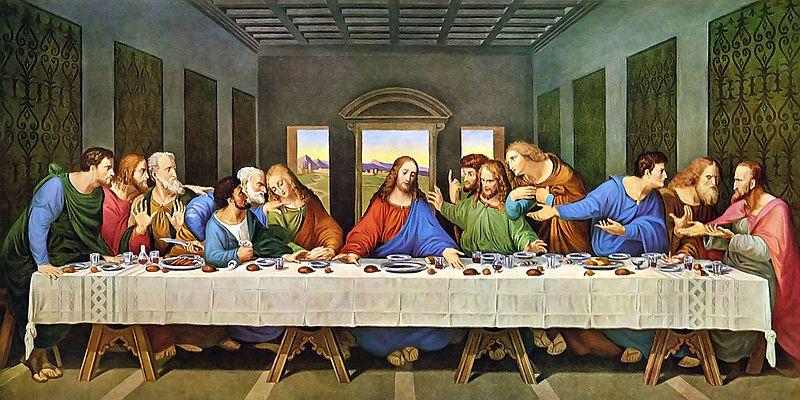

While the origin of this practice is unknown, there are several theories. Let’s take it back to Judas again. We already saw how he may be associated with unlucky 13, and he just might have had a hand in this superstition as well. In Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, Judas is seen knocking over the salt. Because of his Biblical role, people began associating salt with deceit. And, sticking with the Biblical roots, some say that the devil waits behind your left shoulder. So, when you spill salt, it gives the devil an opportunity to step in. What can one do in this situation? Take that salt you spilled and throw it over your shoulder to blind the devil to save yourself!

Leonardo da Vince, The Last Supper, 1496-98 (restored) (Source: Santa Maria delle Grazie church, Milan, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

We don’t know for sure what bad juju spilled salt brings, but if it’s already spilled it won’t hurt to toss it … you know, just in case.

3. Bad News Comes in Threes

Maybe it’s just confirmation bias, but bad news always seems to travel in threes. To this day, when a public figure dies, people wait to see who the next two will be. Why three? What is the significance? It’s really a self-fulfilling prophecy. We are intrigued by groupings of three. One is random. Two is coincidence. Three … well, three peaks our interest. We take this grouping, and we try to find meaning in it.

Is it number mysticism, or is it psychology? Sets of three are appealing and easily delivered. Finding patterns like this give purpose to some. We naturally look for patterns, after all.

While the origin of this superstition is debated, the pattern of three is still a superstition with a strong following to this day. Maybe we’re looking for patterns of three, or maybe there really is some truth behind this superstition. Who’s to say?

4. Brother, Can You Spare Some Luck?

“Find a penny, pick it up. All day long you’ll have good luck.” This simple children’s rhyme rings through the minds of young and old alike. I’ve heard several versions (with some believing that only a penny found heads up is lucky), but the message remains the same: A found penny is a lucky penny. Finding money is lucky, especially if it’s a large bill, but the penny is the currency that shines with special good fortune.

Back in ancient times, many cultures believed metals were gifts from the gods, bringing luck to all that found them. Naturally, metal coins were thought to be especially lucky because they increased your wealth. I know pennies won’t get you very far in today’s world (financially speaking), but I’ll cash in all the luck I can get.

And even if it is just superstition, I still flip over “tails” I find on the sidewalk with hopes of making someone else’s day fortuitous.

5. Don’t Forget to Knock on Wood

Have you ever said something and then quickly “knocked on wood” in order not to jinx yourself? You’re not alone. Perhaps the most common superstitious practice in America today, “knock on wood” is both a widely used phrase and action. In a survey conducted by the Crowdsourcing website, Ranker.com, 18,000 people ranked their top superstitions. Knocking on wood appeared as number one.

While this one is a long held belief, the original source didn’t require individuals to knock on wood – they simply had to touch wood. Medieval churches would often possess wood claimed to be from the Cross itself. By touching the wood, churchgoers would believe that they forged a link to the divine, and that they would receive good luck because of it. But this belief has roots that branch (no pun intended) far outside the Church’s influence.

One of the possible origins of this superstition can be found in pagan rituals. In pagan religions, trees were worshipped and seen as the homes of certain gods. Worshippers would lay their hands on a tree when asking for favors, or would touch the tree as an act of thanks after having good fortune. It was also done to ask for protection.

Both historical instances of this superstition are grounded in the same basic belief – touch a piece of wood to get good luck. It’s a belief that maintains a powerful hold on many people to this day.

So, Are You a Believer?

Of course, these are but a few of the innumerable superstitions that have influenced people from eras and cultures throughout human history. From avoiding black cats to collecting four-leaf clovers, strange traditions are practiced around the world in order to usher in good luck – or to avoid the bad kind.

Maybe these superstitions are just that: superstitions. Or maybe, there is some truth to the myths. Either way, I’m not going to test it. I’ll handle mirrors carefully and continue to toss my spilled salt. And I’d advise you do the same . . . knock on wood.

Ω

Title image: Jari Nyilang. (Credit: Pinerineks, via Wikimedia Commons)