A decade before William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, took England in 1066, another Norman conquest was underway in the south of Italy. And though the reign of Norman kings in Sicily wasn’t as long-lasting as in England, it was arguably the greater achievement. There they created a kingdom renowned for its beauty, riches, and culture, an island of unprecedented tolerance among northern European, Greek, and Arab peoples amid a war-torn world.

◊

The way to Palermo, Sicily, is through a crescent of orange groves on its surrounding hills. Arriving, I found the city dotted with broad palm trees. There’s a grand public square and narrow streets leading from it with small wine bars and walk-up espresso counters. Bakeries and candy vendors beckon with sweets – from licorice, my particular favorite, to fritters dusted with powdered sugar, frosted fig cookies, and custard-filled tarts.

Don’t let the sweets mislead you, though. Palermo owns a bloody history reaching from the recent past to ancient times, one written with swords, bombs, and guns of mafia chiefs and killers, invading armies and ruling tyrants. But while there, I was amazed to find one of the architectural glories of Western civilization: a medieval chapel of other-worldly beauty built by one of history’s most remarkable rulers, the Norman king of Sicily, Roger II.

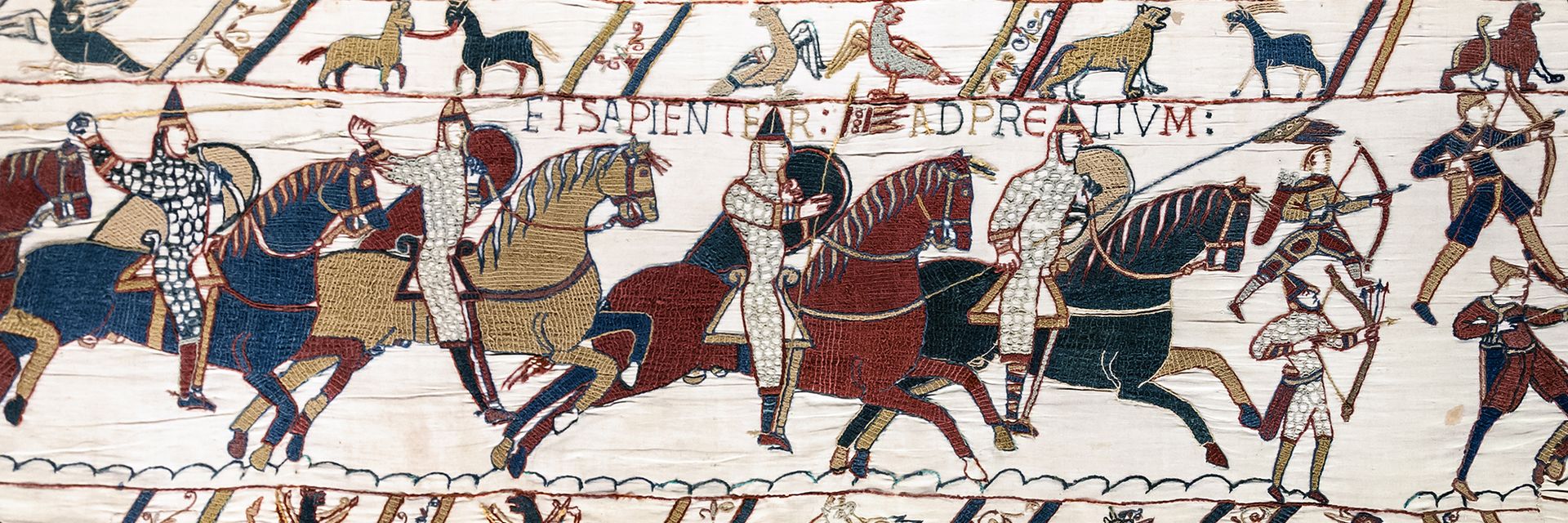

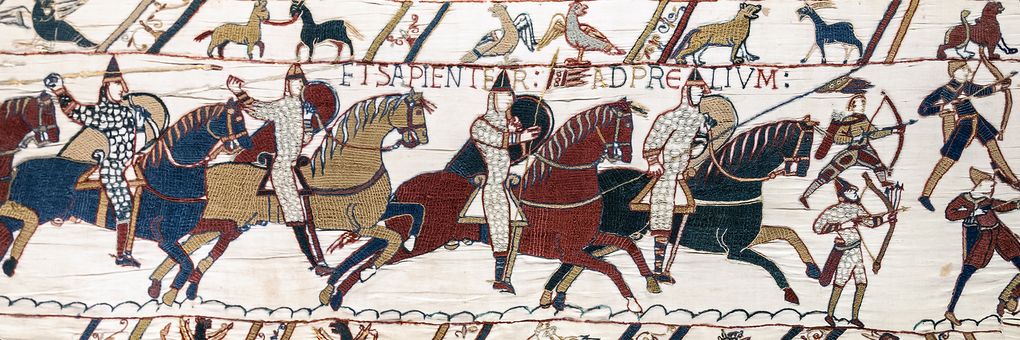

You might not have heard of King Roger, but if English is your native tongue, you’ve almost certainly heard of William the Conqueror. In 1066, he and his Norman troops crossed the English Channel from their native Normandy and defeated the Anglo-Saxon nobles at the Battle of Hastings, a victory that made William King of England. You are probably aware, too, of the Bayeaux Tapestry, which might be history’s first graphic novel, describing the Norman campaign in vivid detail with fighting men stitched across yards of linen. There is also the Domesday Book, that voluminous and detailed survey of William’s new kingdom. And certainly everyone’s familiar with the Tower of London, the castle and prison William built to reign over his conquered subjects.

Sixty years after Hastings, Roger II consolidated another Norman kingdom, this one comprising the lower half of Italy’s “boot,” the incomparably rich island of Sicily (whose population was mainly Greek and Arab), and most of the north African coast. The lands were an astonishing multicultural network of wealth in trade, the sciences, and philosophy.

Roger’s enduring monument is not a notorious castle prison like the Tower of London, but that beautiful chapel I visited one sunny afternoon. It’s called the Palatine Chapel, a narrow and high-vaulted gallery at Roger’s Palermo palace that is literally a dazzling synthesis of Latin, Greek, and Muslim art and design symbolizing the glories of his reign.

The stories of Roger, William, and other great Norman leaders are told in The Normans, a riveting three-part series available on MagellanTV. The skills in arms and governance of these remarkable warriors and wanderers changed the course of Western history.

Who Were the Normans?

The Normans, literally “Northern men,” had been Viking raiders who eventually settled in what came to be called Normandy – the “Northern men’s duchy” – soon after 900 C.E. The invaders gladly accepted Christianity as a term offered by the helpless French king who ceded to them an enormous state along France’s northwestern coast.

Norman interest in Mediterranean affairs came about 40 years later. As related in a chronicle by the medieval monk Amatus, a group of about 40 young Normans, returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, took it upon themselves to repel an attack by Arabian pirates on the Italian port of Salerno. Richly rewarded for their enterprise by the local prince, they returned home with tales of the profitable opportunities available in what historian John Julius Norwich calls the “great cauldron of South Italy.”

The Normans were, Norwich writes, “materialistic, quick-witted, adaptable, eclectic, still blessed with the inexhaustible energy of their Viking forebears and a superb self-confidence that was all their own.” They were “natural wanderers – not just of necessity but by temperament as well … fearless, footloose young men looking for somewhere else, where the pickings would be better still.”

Italy Beckons the Hautville Brothers: Robert and Roger

Substituting the horse for the longboats of their recent ancestors, Norman bands headed south in the decades before William the Conqueror set his sights on England. Their progress was a gradual mercenary campaign of shifting loyalties amid dozens of competing warlords, a Game of Thrones without any magic. The most able of these northern freebooters proved to be 12 sons from a minor noble family, the Hautvilles. With no prospects in France, they drifted south after gaining adulthood, the younger ones seeking employment from their successful elders.

The greatest of the Hautvilles was Robert, a middle child who appeared at the doorstep of an elder brother, by then the count of Apulia. That brother finally posted him to a remote Calabrian castle where Robert and his crew gained a reputation as very capable bandits, preying upon the local barons and monasteries. The campaign earned Robert the added honorific name of Guiscard, best translated as “the Crafty.” According to the Shorter Cambridge Medieval History, he was “a fair, blue-eyed giant,” immensely strong with a voice like thunder. A contemporary, the Byzantine princess Anna Comnena, described him, “in temper tyrannical, in mind most cunning, brave in action, very clever in attacking the wealth and substance of magnates, most obstinate in achievement, for he did not allow any obstacle to prevent his executing his desire.”

The new Pope Leo, having had quite enough of the demands and incursions of the Norman warlords south of Rome, raised an army to drive them out. This proved unwise, and Robert Guiscard was a key commander in the defeat of that papal army in 1053. Leo, now a semi-prisoner in his palace, was resigned to the inevitable and gave the still devout Normans a new assignment – to drive the Byzantine Greeks from the lower Italian peninsula. In the process, the Pope invested Robert Guiscard as Duke of Calabria

Duke Robert set to his new task with enthusiasm, leading to a string of successes, aided now by another young Hautville brother, Roger. Clearing Calabria of Byzantine cadres by 1069, the two then embarked on a campaign to take Sicily.

Palermo: The Prize of Sicily

Peopled by Greek settlers from ancient times, Sicily was one of the first acquisitions of the expanding Roman empire. Soon it became the breadbasket of the nation, and wheat and olive oil from its vast slave estates became the indispensable ingredients for feeding and ruling the city of Rome. Greek remained Sicily’s main language and grain production its central mission after the fall of Rome. It was taken first by the Carthaginian Vandals, then by the Ostrogoths, who were in turn ousted by the Byzantine Greeks. The Greeks retained pride of place until the Arabs landed in 827 C.E., advancing across the island in gradual steps until, by 902, it was entirely theirs.

The Sicilian Arabs, known to history as Saracens to distinguish them from the Arab Moors of Spain, transformed the capital of Palermo, which they called al-Madinah. The Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi described a city of “many gardens, beautiful houses, and canals of fresh running water, brought from the mountains that surround its plain.” The Saracens introduced new crops – lemons, oranges, and sugarcane (as noted above, the Sicilian sweet tooth is well-supplied to this day) – and brought traders of goods from across the world to its ports.

Sicily remained, however, a land of parts – rich but missing a central ruler, its districts overseen by a patchwork of competing emirs and their private armies. This weakness was exploited skillfully by the brothers Hautville when they crossed the narrow Strait of Messina to seize the irresistible island prize.

Palermo, Sicily

After capturing Palermo, Robert left the balance of Sicilian conquest to Roger. He returned to Calabria, from which he launched an invasion of Byzantium, his goal nothing less than capturing Constantinople. Given his track record, he may well have done so, but he had to leave that project for a while to retake Rome, then under the grip of the German Holy Roman Emperor. He succeeded, sacking the city in 1083. Returning to Greece, Robert died of fever in 1085, an era-defining general and ruler unequaled until the advent of Napoleon seven centuries later.

Norman Sicily: Three Cultures, One King

Back in Sicily, the no-less-able Roger secured the last Muslim holdout, the majestic fortress hill city of Enna at the island’s center, in 1087. From Enna’s highest point, it’s possible to see clear across the island, as I was able to do one day, sighting the long line of smoke drifting from the burning peak of Mt. Etna, Europe’s only active volcano, on Sicily’s eastern shore.

At a truce conference, history says Roger promised the besieged city’s emir a vast Calabrian estate and peaceful retirement should he and his troops have, say, the unfortunate luck to be surrounded and disarmed in a nearby mountain pass. Turns out, a few days later that’s exactly what happened. Roger now ruled the entire island and, as Robert’s heir, most of the Italian south. Under his reign, Sicily became renowned for its wealth, learning, and tolerance, an outcome all the more astonishing in a Mediterranean world of endless wars for religious and cultural domination.

.jpg)

Enna, Sicily (Credit: Michal Osmenda, via Wikimedia Commons)

In contrast to William the Conqueror, who ruled England with a mix of might, pervasive bureaucracy, and an official language and legal system imported from France, Roger Hautville chose a different tact. Without an overwhelming armed force, he knew his rule depended on the acquiescence of the existing legal and economic structures – Greek and Muslim bureaucrats and traders. Therefore, Sicilian daily life went on as before: All were allowed to worship as they chose; Saracen brigades served in Roger’s army; and Arabic and Greek remained official government languages, alongside French and Latin. Roger’s son, the future Roger II, grew up fluent in all four.

Though never crowned monarch of Sicily, Roger Hautville left a kingdom to his son, who ruled it as King Roger II.

Hautville’s Norman knights avidly accepted Saracen customs, dressing in long robes and turbans and keeping harems. Neither Roger nor his son supported the two Crusades to the Holy Land undertaken during their reigns, instead capitalizing on Sicily’s position at the crossroad of three cultures. It was a nexus of trade, translation, and scientific study. This remarkable culture of mutual respect was poured into the Palatine Chapel, consecrated in 1140, a Catholic church of dazzling Arabic architecture and ornamentation, and richly adorned Byzantine mosaics.

Where Roger had been the consummate soldier, his son was the quintessential scholar king. Though able to act as ruthlessly as any Norman ruler when opposed, Roger II was by every account handsome, personally warm, highly intelligent, and very fond of what a more decorous age called wine, women, and song. He died, it’s said, of all three in 1154, only 58 years of age. In great credit to his skills as a monarch, Roger II’s son and grandson (both named William) carried on the royal line until the lack of a male heir gave the Sicilian throne to a German cousin at the end of that century. Sicily’s golden age was over.

The Normans Fondly Recalled

Either in spite or because of its long and violent history, Sicily’s paternalistic culture places a high premium on mutual respect, perhaps a vestige of Norman rule. What can’t be denied is the obvious regard Sicilians continue to hold for their former Norman rulers. They are the subjects of festivals and epic poems, their legends told in Palermo’s remaining puppet theater, where I watched Norman knights in armor wield broadswords against giant Saracens armed with scimitars and shields – turbaned heads flying off robed bodies.

Puppet Theater, Palermo, Sicily (Credit: Dennis Jarvis, via Wikipedia)

I was in Sicily retracing family origins. Three of my grandparents were born in a hill town halfway between Palermo and Enna, one of them from a supposed Norman family. One uncle, uniquely fair-haired and blue-eyed, was evidence that might be so. Last year, a genetic test likely settled the matter – I share three percent of my DNA with the population of northwest Europe, where Normandy lies. True to the line, my people quit Sicily for greater opportunities some time ago.

Ω

Title Image: Bayeux Tapestry (detail), 11th century, Musée Tapisserie de Bayeux