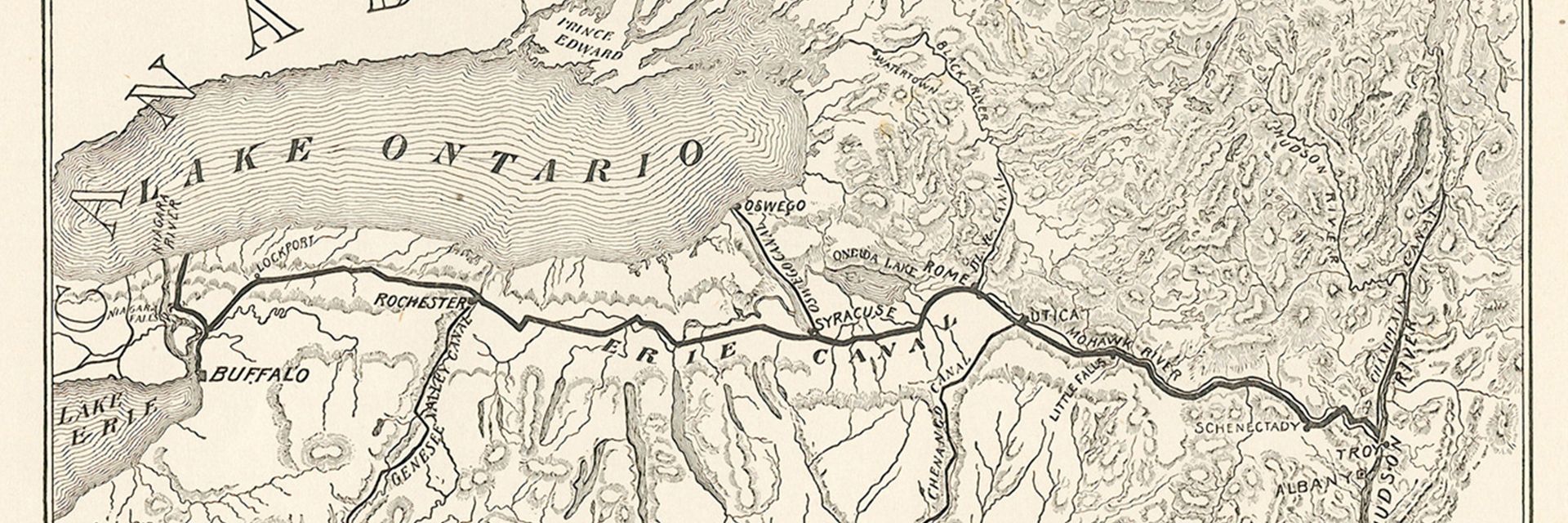

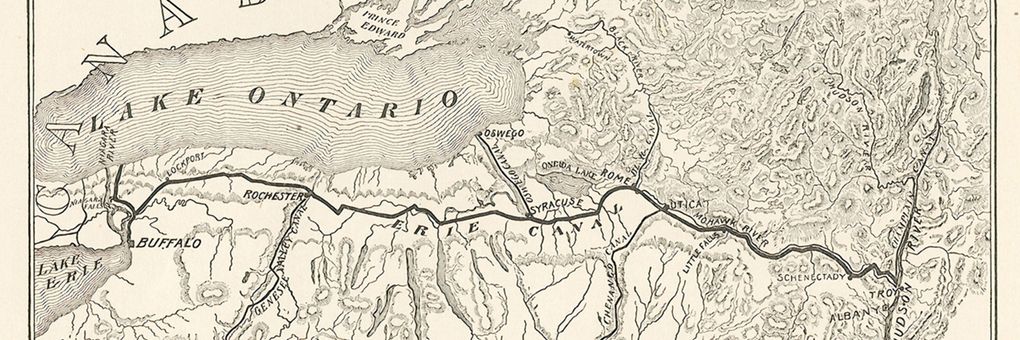

Now an overlooked part of the country, much closer to Canada than its state’s signature city, western New York was once young America’s Wild West. Indian wars, pioneers, boomtowns, religious upheavals, and rapid economic expansion from the late 18th to the early 19th centuries set in motion changes that would eventually sweep across the continent. Energizing it all was the new Erie Canal, considered far and wide to be the engineering marvel of the modern world.

◊

Having grown up in western New York State, I’ve had trouble explaining to people from other parts of the country where it belongs in the rest of the nation. It is not the East Coast (my hometown of Rochester is 350 miles from New York City), and it certainly isn’t New England.

Neither is it the Midwest. Ohio’s eastern border is 120 miles from Buffalo, New York State’s westernmost city. Rochester and Buffalo are closer to Toronto than Cleveland. Overwhelmingly rural, a land of cloudy, deep winters, upstate New York is a long drive from anywhere else, a place apart.

Though overlooked now, known for blizzards and a luckless football team, it was for a time America’s first far west. It’s where Western boomtowns, armed conflict with indigenous people, and the notions of American expansion and Progress (with a capital P) first appeared, a wild landscape that gave way to industrial and agricultural development in less than a generation before 1840.

An “Artificial River” Tames a Wild Landscape

It all happened because of the Erie Canal. Now remembered, if at all, for an old song, the canal opened fully in late 1825 and was hailed immediately as the engineering marvel of the early 19th century. Constructed by the state of New York to aid private enterprise, it was the model for every large-scale transportation project to come, from railroads to the U.S. highway system.

The Appalachian mountain chain ends in New York where the Catskills give way to a wide valley through which the Mohawk River runs east-west to join the Hudson River near Albany. It is the broadest gap in a mountain chain that stretches to Alabama, a natural barrier to settler expansion for two centuries.

In the War for Independence, the Continental Army mounted a two-year campaign through the valley to wipe out England’s Iroquois indian allies from outside Albany into what’s now Ontario, Canada. A 1797 treaty with the main Iroquois Seneca nation consigned it to reservations, mainly on large tracts of land south and east of Buffalo.

When the conclusion to the War of 1812 ended all British designs on western New York, settlement began in earnest. Development was first clustered at Rochester, where the Genesee River drops 200 feet, including a nearly hundred-foot waterfall, in the space of only a couple miles before it enters Lake Ontario. This geological quirk favored the establishment of water-powered mills for grain and lumber.

Buffalo, 60 miles to the west, where the Buffalo River enters Lake Erie, had been an outpost for the fur trade for more than a century. And Syracuse, 90 swampy miles east of Rochester, was the site of vast salt deposits, the residue of an ancient ocean, that comprised the country’s main source of that crucial food preservative.

New York Governor DeWitt Clinton proposed connecting the three settlements to Albany via an artificial waterway – and from there to New York City, 150 miles down the broad Hudson River. As a result, by 1840, Buffalo had grown from a village of 200 people to a city of 18,000.

The Erie Canal at Rexford, New York (Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The Erie Canal: An Engineering Marvel of the Age

Clinton’s canal project, begun in July 1817, paralleled the Mohawk River westward before turning north to link the three frontier towns. Sections were opened as they were completed, with the full 363 miles of the canal finished in October 1825. Dug by work crews of mainly Irish immigrants, “Clinton’s Ditch,” as skeptics called the project, was 40 feet wide with a water depth of four feet. A decade later it was expanded to 70 feet wide and seven feet deep.

Moving west, the canal raised and lowered boats through 83 locks. More impressive to contemporary witnesses were the 18 aqueducts that carried the canal above chasms and rivers. It crossed the Genesee River in Rochester by way of a stone arch bridge slightly over 800 feet long, then considered one of the engineering marvels of the world.

As canal construction progressed, engineers developed new methods to clear timber efficiently and pull up stumps in the canal’s path, and a concrete that could harden underwater was invented to fix the problem of leaks.

The total cost of the canal was a little over $7 million (some $114 million today). DeWitt Clinton had the last laugh over canal skeptics the first year of operation. Even with the canal closed in winter months, the toll collected on shipped goods exceeded the construction bill. The state’s canal debt was fully paid in 12 years.

The waterway created a new class of wealth based on industrial development, not agriculture or trade. An Irish immigrant, William James, who ran an Albany tobacco business and dry goods store, became one of the nation’s first millionaires. An early canal backer and cagey investor who developed the salt works around Syracuse, his fortune was, at the time, second only to that of fur magnate John Jacob Astor.

James’s grandsons, the psychologist William James, and his brother, the novelist Henry James, are central figures in American philosophy and literature. Both received regular income from rents paid on inherited property in downtown Syracuse.

Rochester’s grain works and sawmills produced most of the canal boats and much of the flour and lumber that was mainly sent east. German immigrants arrived in Rochester in the 1840s, bringing the trades of lens grinding and cabinet making. The combination of the two led the city to become the country’s leading center for optics – the Bausch & Lomb company being the most prominent – and the manufacture of cameras. Rochester was a center for photography decades before a young bank clerk and amateur chemist named George Eastman started his dry plate – later named Kodak – company there in 1880.

The Canal’s Success Magnifies America’s Fundamental Problem

This eruption of innovation and outflow of riches did more than benefit the region. New York City became the main depot for dry goods headed west, and receiver of western produce, lumber, salt, and livestock. This commerce allowed it to surpass Boston and Charleston as the most important, and fastest growing, seaport on the East Coast. The industrial expansion and population movement enabled by the canal supercharged the northern economy. It soon looked and felt very different from the agrarian system of the southern slave states.

The canal was celebrated as a boon for independent working people, a feature of a free democratic nation quite at odds with the brutal realities of southern slavery. This difference would only become more obvious in the years to come. The canal became the main conduit for settlers bound for Ohio, Indiana, and points west. This expansion across northern latitudes brought into sharp focus the problem of whether the West would be settled as free or not.

The Erie Canal at Buffalo, c. 1908 (Image Credit: Canal Society of New York State)

In The Artificial River, historian Carol Sheriff writes that the canal’s success birthed the American idea of Progress – the notion that material and technological advancement, of constant improvement, combined with a westward Manifest Destiny, was the driving force of the young nation.

Yet even as those ideals came to define the United States, the project that first energized them faded from view.

Modern America Appears, and Leaves the Canal Behind

After two extensive expansions, the canal remained a useful conduit of freight into the 1950s. But by the middle of the 19th century the New York Central Railroad, which hugged the Erie’s route, was the main mover of passengers, mail, and produce.

But the changes wrought by the old canal indelibly transformed the nation’s landscape, and let loose its spirit. A new commerce beyond old borders and traditions made western New York America’s first West, where old rules didn’t apply and new ideas were set free.

In 1827, in Palmyra, a canal village 20 miles east of Rochester, Joseph Smith had his Mormon revelation of angels and Christ among the Indians. By the 1830s, Rochester became the epicenter of a decade-long evangelical Christian revival of millennial passions that powered movements for women’s suffrage and the abolition of slavery.

The first women’s rights convention was held in Seneca Falls, 40 miles west of Syracuse, in 1848. Four years later, the ex-slave, and anti-slavery crusader, Frederick Douglass moved his abolitionist newspaper, The North Star, to Rochester, where one of his neighbors was Susan B. Anthony.

In Arcadia, another canal town, in 1847, the Fox sisters claimed to have communicated with dead spirits by way of table rapping. They gave theatrical seances in Rochester, and fewer than ten years later the Spiritualist movement had a million believers. The Spiritualist community of Lily Dale was established south of Buffalo in 1879 and remains active today.

A New Era Dawns with a Forgotten Star

One afternoon, on a hometown visit, I went looking for the final resting place of America’s earliest celebrity, the first person to gain widespread fame for doing something unconnected to war, politics, or religion. The canal created a region where daring and skill could render great rewards or disaster, sometimes both, for anyone willing to risk a try. This was true in business, and for a new economy of self-promotion and ballyhoo where fame was earned just by drawing a crowd.

And here, the daredevil Sam Patch, a former mill worker famous mostly for being himself, led the way. In 1828, Rochester was the site of the horrific climax of his brief and unlikely career.

The Genesee River High Falls in Rochester, New York (Photo: Joe Gioia)

He stepped, or rather jumped, into the spotlight at a bridge-raising at the Passaic Falls in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1827. Age 20, Patch lept without warning from a cliff before thousands of people. He hit the water feet first, straight as a rod, and swam away to become famous overnight.

A year later, now promoting himself with handbills, and earning money by way of appearance fees and spectator donations, Patch repeated the stunt at Niagara Falls to greater renown. By then he was traveling the western frontier with a black bear for a pet, and drinking heavily.

In Rochester, headquartered at a tavern, he had a scaffold built above the city’s nearly 100-foot waterfall. His jump on November 11th did not draw enough people or cash, so two days later, on Friday the 13th, he tried again.

This time, before 7,000 onlookers, Patch lost his balance halfway down, hit the water on his back with a slap heard above the roar of the falls and disappeared. The anxious crowd waited in vain for him to surface. Early the next year, Patch’s frozen body was found miles downriver and buried nearby.

Like the canal that brought him west, America’s first celebrity was soon enough forgotten. It took some doing, but I found his grave in a small cemetery, under some trees off a busy street and next to a big apartment building with a view of the Genesee gorge and Lake Ontario.

He has a large headstone now, contributed by history lovers over a half century ago. It replaced a wooden board. “Sam Patch” that one read. “Such is Fame.”

Ω

Title Image source: Wikimedia Commons.