After a rocky, war-interrupted birth that caused the cancellation of the entire first festival, it took seven years and the death of one of the founders to bring the Cannes International Film Festival back to life in 1946. This is the story of the star-crossed attempt to mount that first festival premiere, the fraught background to the planning, and the eventual true first Cannes Festival in 1946, following World War II.

◊

By any standard, the pre-premiere gala ball for the first Cannes International Film Festival, in late August 1939, was an unmitigated disaster. Gale-force winds and torrential rainfall visited chaos upon Cannes, France, that evening, ruining the outdoor décor, toppling seaside tents, and causing a complete shutdown of the evening’s festivities.

But that wasn’t nearly enough to capsize the entire three-week festival. The seismic shock that leveled the event rolled in from the north, centered in Germany. It caused the cancellation of the entire festival just days before the date of its planned start – September 1, 1939, the day Hitler invaded Poland.

Not surprisingly, the crowds gathered in Cannes for the festival had already begun to scatter in the days preceding the blitzkrieg, as Germany’s intentions became clear. The festival organizers, too, foresaw the portents clearly and canceled the event on August 27. Yet their plans had begun with lofty intentions. This was to be the festival of, by, and for “free nations,” with scorn in particular for Nazi-controlled Germany and, even more for Benito Mussolini’s fascist state of Italy.

The Role of the Venice Film Festival in the Creation of Its Cannes Rival

One year prior, in September 1938, the Venice International Film Festival, in its sixth year, was the site of an international scandale. This incident reverberated for months afterward and sparked the idea for an alternate festival – sponsored by the then-free nation of France – that promoted the ideals of liberty, equality, and freedom. What was the source of this international outrage?

At the closing ceremony in Venice, when the award for best film was announced as a tie, eyebrows were immediately raised. This had never happened before! Then the winners were announced: German and Italian films shared the award! And an uproar ensued.

Both films were despicable acts of propaganda. From Germany was Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia, a loving (and sometimes lustful) look at the Aryan race’s finest specimens. The film was essentially a big, two-part follow-up to her masterpiece of Nazi propaganda, Triumph of the Will (1935). And the Italian co-winner, which also was awarded the Mussolini Cup, was Luciano Serra, Pilot, a film celebrating the noble workers of fascist Italy made with the involvement of Mussolini’s son, Vittorio.

The sheer gall of it was too much for many in the auditorium. Olympia, in fact, shouldn’t even have been in competition, as it was not a narrative feature, but rather a documentary (if it can be dignified with the term). The violation of the festival's rules could have meant only one thing: The decision had the thumbprint of the Nazi Party all over it, and specifically of Joseph Goebbels, the Party’s Minister of Propaganda.

Many individuals exited the hall immediately to register their disgust for the charade. In addition, the entire delegations of Britain and the United States vacated their seats en masse.

What is to be Done? The Creation of a Film Festival in Cannes, France

Two Frenchmen who had been at that scandalous award-night disaster soon met and realized that they shared a vision. Philippe Erlanger was the head of France’s Department of International Artistic Exchange. Appalled by what he’d encountered in Venice, he sought to build a community of artistic, freedom-loving citizens to come up with a creative response to what he saw as the “barbarity” of fascism and Nazism.

Jean Zay pledged to create a new international film festival representing the world’s free nations. (Source: Gallica Digital Library, Meurisse Press Agency, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

Erlanger was soon introduced to Jean Zay, at that time France’s youngest-ever Minister of Education and the Fine Arts. Zay had also witnessed the artistic atrocity in Venice and was immediately sympathetic with Erlanger’s aims. Together they pondered what an appropriate response would be. Soon it became apparent to both that it was imperative to fight a Nazi/fascist film festival with a free countries’ film festival.

Erlanger and Zay were a uniquely well-situated pair to organize an international film festival. First, both were effectively officials of the French state, and both had a stake in international fine arts. They moved quickly, and their enthusiasm was infectious. Before long, the French government agreed to officially sponsor its first international film festival. The southern French resort town of Cannes, near Nice, was selected to be its home.

Their own propaganda (or, let’s say, informational) needs would be met by aiming squarely at Venice – and shooting. If the Venice Film Festival was scheduled for early September, then so would Cannes. They even went so far as to set the same date, Friday, September 1, for their opening night festivities. And whereas Venice’s film selections were full of nationalistic propaganda, Zay declared that there would be no war propaganda – no propaganda at all – allowed in their official selections.

For a deep dive into the drama behind the failure of the first Cannes International Film Festival, and its aftermath, seek out the documentary Cannes: The Freedom Festival on MagellanTV.

Plans for a Film Festival Greater than Any Other – Especially Venice

To make this festival particularly noteworthy, even spectacular, Zay spent time visiting the U.S. in the spring and early summer of 1939. He met with President Roosevelt, who declined to give the festival official government support due to the U.S. position of neutrality at that time.

Zay was more successful with the American film industry. What he lured the moguls with had to stir their nationalistic pride as well as their quest for expanded profits. Zay offered American film studios a four-point program for the festival:

- Promote the festival as a large-scale film diplomacy event.

- Establish it as a symbol standing against the fascist (and corrupt) Venice Film Festival.

- Bring together films of the “free nations.”

- Affirm the essence of French cultural policy.

Hollywood especially liked Zay’s other offer to the U.S., which was to seal a commercial accord to give U.S. films unfettered access to the French market. This opened the floodgates of American cooperation with Cannes. Though each “free” nation was invited to enter at least one film in the fest (Germany and Italy pointedly refused to participate), the U.S. had nine films in competition at Cannes 1939. In addition, there were submissions from other free (at that moment) nations, including France and the U.S.S.R., as well as Britain and the Netherlands.

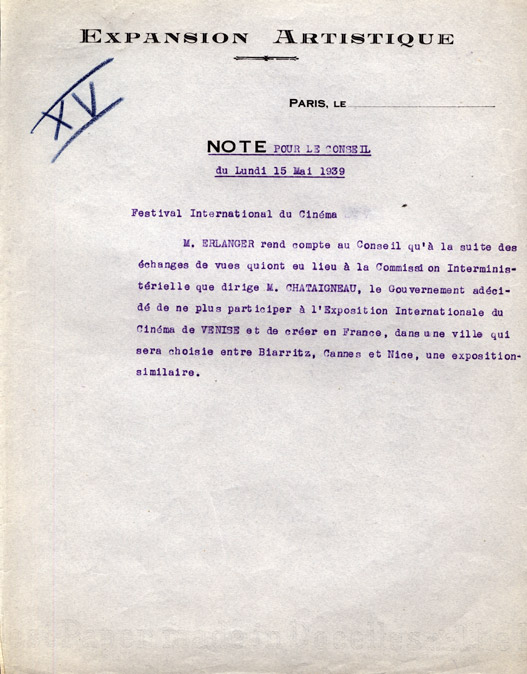

Note from 1939 proclaiming the French government's decision not to participate at the Venice Film Festival, but to host its own festival (Source: French government, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

MGM was so enthusiastic about this new international festival that they hired a cruise liner to take American film stars by Atlantic passage from New York directly to Cannes. Celebrities booked on this ship included Barbara Stanwyck, Spencer Tracy, James Cagney, Cary Grant, George Raft, Tyrone Power, and Gary Cooper, among many other stars of the time. But the packed ocean liner beat a hasty retreat to NYC when fears of war became increasingly apparent in Europe. It was certainly no ship of fools!

Festival Founders Caught Up in Chaos and Tragedy of War

The founders of the Cannes Festival were soon caught up in the burgeoning world war. Philippe Erlanger spent part of the conflict hiding out after France was conquered by, and began to collaborate with, Nazi Germany. A Jew, Erlanger managed to survive in Cannes at the Grand Hotel, and later holed up in a small bedroom in Gascony to avoid capture by the Germans, who were sweeping southward through France.

Jean Zay took the declaration of war as a personal call to serve his country and signed up immediately with the French military, for which he was commissioned as a second lieutenant. He retained his government position during his military service, at least until the fall of “free” France in 1940. Tragically, Zay soon found his official positions wouldn’t save him from the antisemitism of Marshal Pétain and the Nazi collaborators of the Vichy government.

Zay had a Jewish grandfather, and though he was raised Christian, his family history in Orléans made him suspect – and one-quarter Jewish. Following the fall of France, Zay attempted to flee to North Africa to join a group of French patriots who were planning to set up a state in exile to oppose Vichy rule. The plot was not successful and Zay, identified now as an enemy of the new government, was arrested, charged with desertion of his military post, and imprisoned.

Although Zay was allowed to communicate by letter with family members, and was by all accounts a model prisoner, his position within the government deteriorated rapidly. He was denounced as a “radical” and there were calls for his execution.

In his private writings preserved by his family, Jean Zay mused about his fate behind bars. Taken out of commission as a free and outspoken defender of liberty, he said, “My freedom was amputated.”

Finally, one day in 1944, a year before the end of the war, Zay met his shameful and ignominious demise. Removed from prison under false pretenses by agents of the government pretending to be freedom-fighters, he was driven to a wooded area, shot to death, and hidden under rocks, not to be discovered until 1946.

In the aftermath of the Second World War’s tragic toll of millions of victims, Philippe Erlanger was shocked and elated to be contacted by the restored free French government after the war. He was invited to revive the Cannes Film Festival – as if no time had elapsed since the dark days of 1939. And so, in September 1946, France again unveiled its annual international festival and, with a few hiccups, the event has run annually since then. Over the years, it has become the world’s largest commercial film festival, responsible for introducing many film stars, as well as a long chain of influential films, to the world.

80 Years Later, Jean Zay’s Legacy Is Reborn

In November 2019, in Orléans, France, the town of Jean Zay’s birth, and a full eight decades from its originally scheduled date, the “1939 Cannes Film Festival” was finally held. Endorsed by Zay’s two daughters, and lovingly reconstructed by fans and scholars of film and film history, the entire roster of 30 films was screened.

A similar, smaller event sponsored by the Cannes Film Festival, in 2007, screened 17 of the original 30 films. An honorary “Palme d’Or,” the festival’s highest honor, went to Cecil B. deMille’s saga of Western development, Union Pacific.

.jpg)

Actors Jimmy Stewart (r.) and Claude Rains (l.) in a crucial scene from the award-winning 1939 feature, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. (Source: Columbia Pictures, Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

Notably, in 2019, when all the original films were presented, another honorary Palme d’Or was awarded to Italian American director Frank Capra for his masterpiece of “the human comedy” and American classic, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

No doubt, the late Jean Zay, who fought tirelessly for the spirit of freedom in the art of filmmaking, would have been pleased. After all, as American hero Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title image: Hand-tinted postcard of Canne, 1930s (Source: Public Domain, via Wikimedia)