Riding a wave of American social anxiety brought on by the disrupting changes of new technologies and mass immigration, the Ku Klux Klan reappeared on the American scene in the 1920s. It was promoted by a pair of public relations executives who profited richly from its national expansion, and relied on popular myths of white supremacy drawn from a blockbuster movie. But the new Klan soon collapsed from a mix of hypocrisy and corruption at severe odds with the highly moral vision of American values it presumed to uphold.

◊

In 1915, the movie director D.W. Griffith released a work that is both a landmark of cinematic art and a rabid work of racist propaganda glorifying some of the worst aspects of the American character.

Birth of a Nation was the first feature-length film, set in the years immediately following the Civil War. It bestowed a heroic status on terrorists and murderers who, masked and at night, inflicted lethal violence on those African-Americans living in the old Confederacy who presumed to vote, own property, or otherwise challenge the apartheid system of black servitude that quickly replaced the smashed slave economy.

The film was both part of, and reaction against, technological and social transformation of American society. Movies, phonographs, the automobile, and radio remade the social and media landscape. They provided exciting new opportunities for mobility – and therefore sexual freedom – and a tidal wave of unfamiliar images and music, especially jazz, at odds with traditional notions of Protestant morality. Needless to say, many conservative citizens, in small towns and big cities, found these developments deeply upsetting.

The Klan so glorified by Griffith was mainly crushed by U.S. Army troops under the express direction of President Ulysses S. Grant. But that defeat did not stem the tide of laws and court decisions in the late 19th century that effectively enacted Jim Crow segregation across the South, something that lasted into the 1960s.

The son of a southern slaveholder, President Woodrow Wilson loved Birth of a Nation, and made it the first movie ever shown at the White House. He said “it is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is also terribly true.”

Capitalizing on the phenomenal success of Griffith’s film, and using its thrilling images of powerful and righteous enforcers of white supremacy, an Atlanta physician and itinerant preacher named William J. Simmons founded a new version of the Klan based on his many memberships in other fraternal organizations.

A better joiner than leader, Simmons’ early Klan went nowhere until, in 1920, he hired Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Clarke, two Atlanta executives in the new field of public relations. Promised 60 percent of all proceeds, Tyler and Clarke took the Klan nationwide. Their calculation was to promote it not as a loose organization of small-town terrorists but a broad-based social club on par with older, very popular fraternal groups like the Elks, Masons, and Rotary.

Mass Spectacle for a Mass Market

From a newspaper family – Clarke’s father owned the Atlanta Constitution, where his brother was an editor – he employed the reach of print media to greatly expand the Klan’s appeal. He used newspaper ads to provide membership applications, press releases, and special publications that promoted Klan values without mentioning its name. He also organized a network of speakers by giving free memberships to preachers skilled at reaching large crowds on an emotional level.

As detailed by historian Linda Gordon in her book The Second Coming of the KKK, the project was, from the start, intended as a money-making enterprise. It was essentially a system of local franchises established from a national office in Atlanta requiring a steady income stream from initiation dues, and the sale of branded merchandise. The fees ensured that most Klan members were from the middle class, the biggest moneymakers being the official robes and hoods that could only be purchased from Klan headquarters.

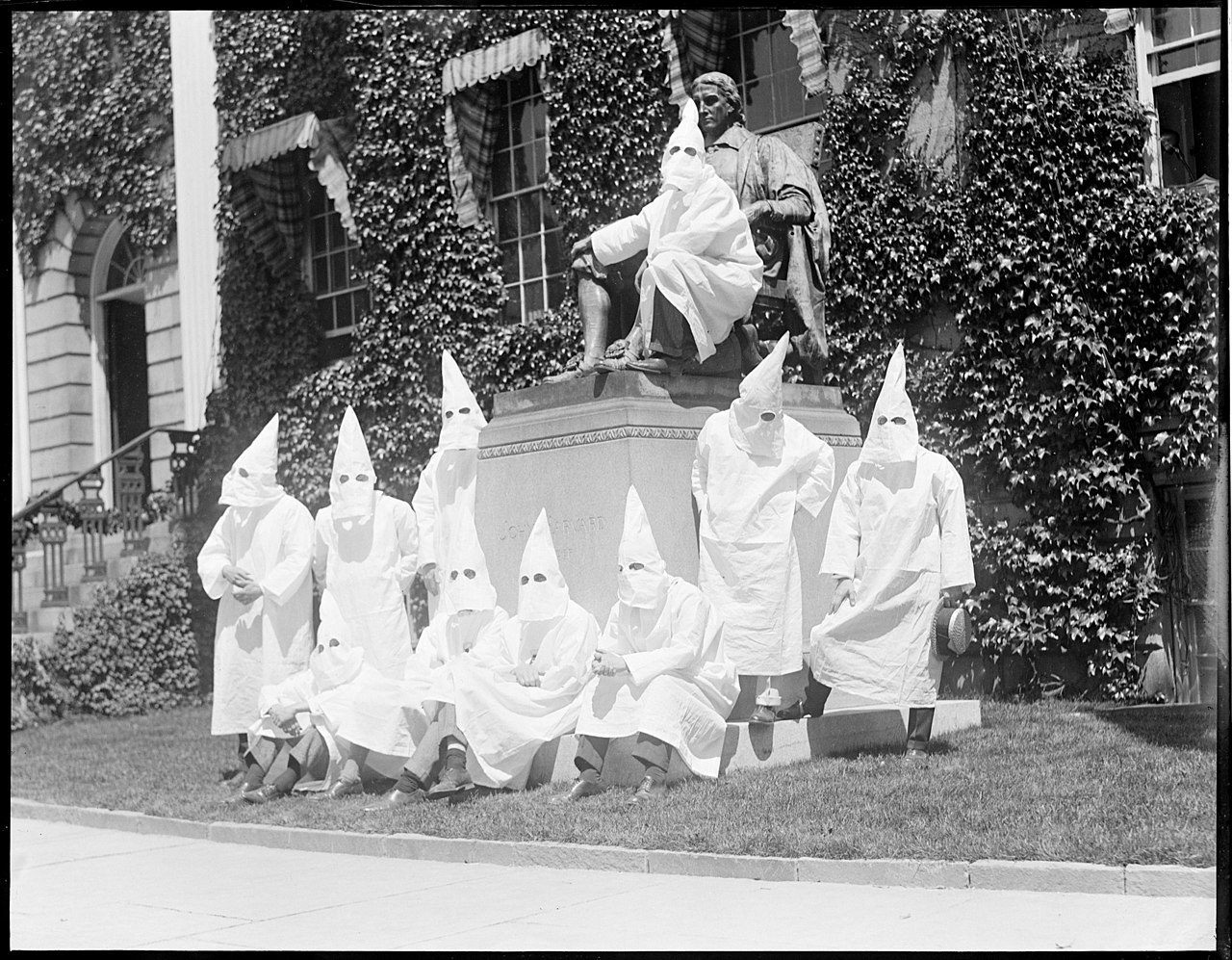

Klan members at a 1922 rally in Muncie, Indiana – in robes purchased from KKK headquarters (Source: William Arthur Smith, via Wikimedia Creative Commons)

The revived Klan, though absolutely grounded in images drawn from the increasingly influential movie technology and taking advantage of expanded media connections, was promoted as a moral bastion. It presented itself as a vanguard of white, Protestant, middle-class citizens opposed to what they saw as the nation’s ongoing moral decline – a patriotic, upstanding movement exclusively for people like themselves, not anti- anyone.

The Klan Targets the Newest Americans

And because the subjugation of black people was at full strength in the 1920s, as it expanded across the country, the Klan mostly paid scant attention to African-Americans, targeting instead those they considered the enemies of true American order – Catholics, Jews, labor unions, and immigrants of every type but especially “nonwhite” Italians, Asians, and Mexicans.

The new Klan supported, at least publically, Prohibition and women’s suffrage. The former was seen as a stand against the social pleasures of German, Irish, and Italian immigrants. The latter was a tactic to bring more Protestant white voters to the polls.

These prejudices were never far from the American mainstream. And the fondness of Americans to join social clubs was seen as a hallmark of the country’s unique brand of democracy. The revived KKK’s success came from combining these two elements of national life and giving them a dazzling new spin with dramatic costumes and public spectacles.

Once a Klan franchise was established anywhere, local parades, picnics, and large nighttime ceremonies that climaxed in cross burnings were a large part of its appeal. While the southern Klan mainly used cross burnings to target specific victims on private property, the expanded Klan held these events in public parks, often at the highest elevation in town. Klansmen insisted these grim occasions were nothing more than displays of civic pride, certainly not broad efforts at intimidation.

A City Fights Back

As popular as the Klan became, plenty of people did not buy what it was selling. The NAACP, founded in 1909 to pursue racial justice for black people, immediately criticized Birth of a Nation and kept a light shining on lynchings and KKK activity. Big-city newspapers, with large immigrant readerships, called out the Klan’s un-American nativism. And at least one city, Buffalo, New York, literally fought fire with fire to drive the Klan out of town even as it was becoming established elsewhere.

As was so often the case with immigrants, when Italians came to America they moved to the same cities, towns, even neighborhoods where they could be with earlier arrivals from home. Whole villages of neighbors and relatives could be reconstituted in tight proximity in a strange and sometimes hostile American landscape – on the Hill in St. Louis, say, or Boston’s North End, or, for my six Sicilian great-grandparents and their children, around Mechanic St. in Buffalo.

Keep in mind that by 1920 Buffalo’s Catholic immigrants had already made their cultural mark on the city and were moving into its professional and political ranks. These confident, self-made men and their children presented a very different picture from the dirty, huddled masses of 19th century caricature. This example of American success is probably what bothered Klan members most.

The new Ku Klux Klan opened an office in downtown Buffalo in 1921, and in October 1922 initiated 800 members in a public ceremony and cross burning. The terminus of the Erie Canal, Buffalo had always been a rowdy inland port town, on par with St. Louis or Chicago. It was an industrial and rail center that for decades drew waves of mainly Catholic immigrants from Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Poland. Hard-working and hard drinking, Buffalo was known for its rich nightlife and, though Prohibition reigned in 1922, untroubled access to Canadian liquor and beer right across the Niagara River, not to mention wine from the many vineyards south of the city.

Buffalo’s civic culture was everything the KKK hated – polyglot, tolerant, and fun-loving, and so it was able to recruit like-minded followers in and around the city. The Klan’s first mistake was to get involved in the 1921 mayoral election that pitted a German Catholic brewery owner, Francis Schwab, against a Protestant lawyer named George Buck. Schwab, campaigning on Prohibition repeal, won a close contest, becoming the city’s first Catholic mayor.

In April 1924, 18 months after the mass Klan initiation, the home of a Klan-supporting minister was bombed. On July 3, the KKK’s downtown office was ransacked. Among the papers taken was a 32-page directory of local Klan members. It was put on public view at police headquarters, where thousands saw it. Many of those listed quickly quit the organization.

Enraged Klan officials sent their own detective from Atlanta to investigate the theft of the membership directory. He soon identified a police undercover agent named Edward Obertean, who had infiltrated the organization. On August 31, 1924, the Klansman confronted Obertean outside a small home on a residential street. The two men exchanged gunfire, killing each other.

The ensuing outrage and police investigation effectively crushed the local KKK chapter. In 1925, Schwab was reelected mayor in a landslide. The Klan closed its Buffalo office that same year.

The Klan’s Political Influence Peaks

Elsewhere in the nation, the organization was at the height of its popularity. On August 8, 1925, a Klan march in Washington brought between 25,000 and 50,000 robed demonstrators to march in a long parade in front of the Capitol building. It was a display meant to flex political power and demand further restrictions on immigration.

There is no question that Klan members were elected to high public office – 11 governors, 16 senators, and dozens of U.S. House members. It was believed President Warren G. Harding was a member. True or not, neither he nor any president from Woodrow Wilson to Herbert Hoover condemned the group.

Other Klan members were future Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, and president-to-be Harry Truman, who quit when he was told not to socialize with Catholics. Another Klansman was sculptor Gutzon Borglum, who worked on the Stone Mountain monument to Robert E. Lee before undertaking his work on Mount Rushmore.

Despite its outsized political power, the revived Klan had two flaws fatal to long-standing growth. The first was that it was fundamentally a pyramid scheme relying on money to flow upward from a constant supply of new recruits. Soon enough, everyone who wanted to join had done so. The KKK reached an estimated peak of five million members, over four percent of the population, but half of that number soon quit, either, like Truman, dismayed by its brutally racist agenda, or outraged by examples of rank corruption among the leadership of a supposedly moral enterprise.

The Ku Klux Klan of Harvard University, 1924 (Source: Public Domain, via Wikimedia)

A Gruesome Murder Leads to the Klan’s Demise

While cases of financial irregularity were common on the local level, the fatal blow to the national organization fell during the sensational trial of David Stephenson, the head of the Indiana Klan. Presumed the most powerful man in the state, he was tried for the gruesome kidnapping, rape, and murder of his secretary, Madge Oberholtzer. Found guilty, he provided a long list of public officials who had accepted Klan bribes, leading to further prosecutions. In the wake of this, the charade of a national, influential, patriotic KKK kompletely kollapsed.

Conceived first in the light of a bright movie fantasy, promoted by mass communication, and exploiting the social dislocations caused by new technologies, a national Klan could not survive the real-world exposure of its fundamentally corrupt and vicious nature.

The pressure of new technologies and social dislocation are built into the American scene. It is wise then to recognize that civic threats like the 1920s Ku Klux Klan revival can and will reappear (as, in fact, it did in the 1950s and ’60s). These recurring infections will always be opposed by other built-in aspects of our sprawling democracy – the force of truth, the rule of law, and a commitment to national ideals of tolerance and inclusion – that a persistent minority of Americans will always have trouble accepting.

Ω

Title Image: March 17, 1922. Members of the Ku-Klux-Klan about to take off with literature which was scattered over the Washington’s Virginia suburbs during a Klan parade by Voice of America via Wikimedia Commons.