A century after Andrew Carnege’s death, a small town in Montana still prizes his gift of a public library.

◊

Early one Montana winter morning a few years back, I saw from my living room window our head librarian clearing snow from the sidewalk and long flight of front steps to our town’s Carnegie library. It was my first winter there, and, being neighborly, I went to help, something I’ve done most big snow days since.

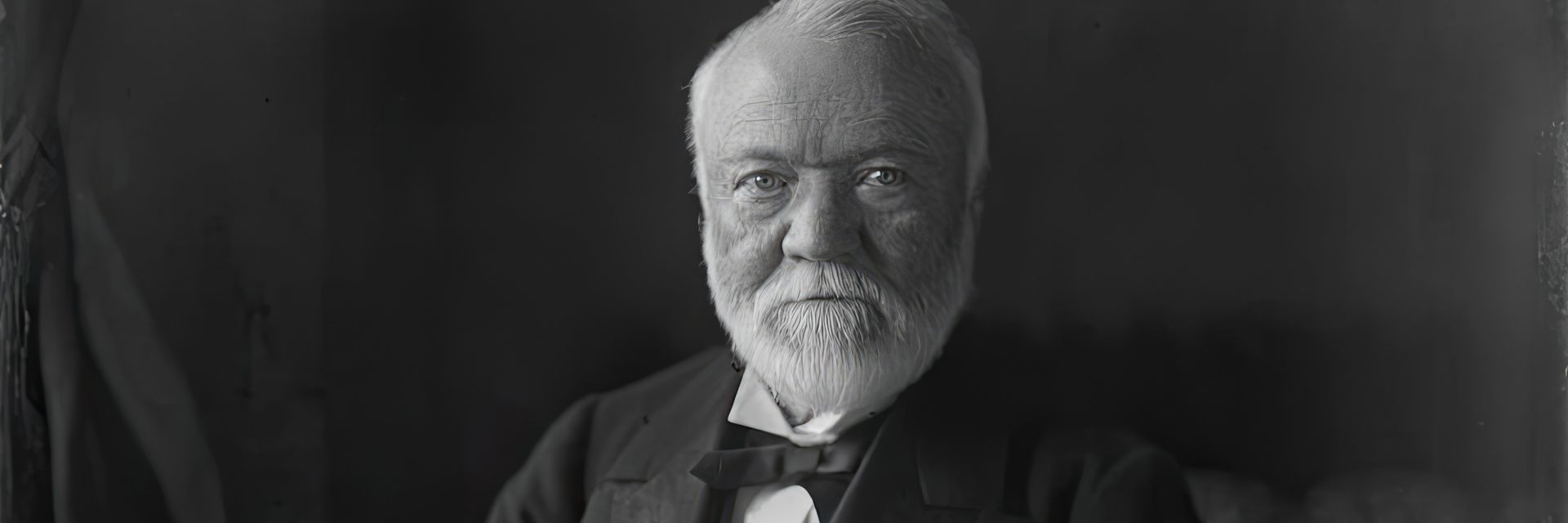

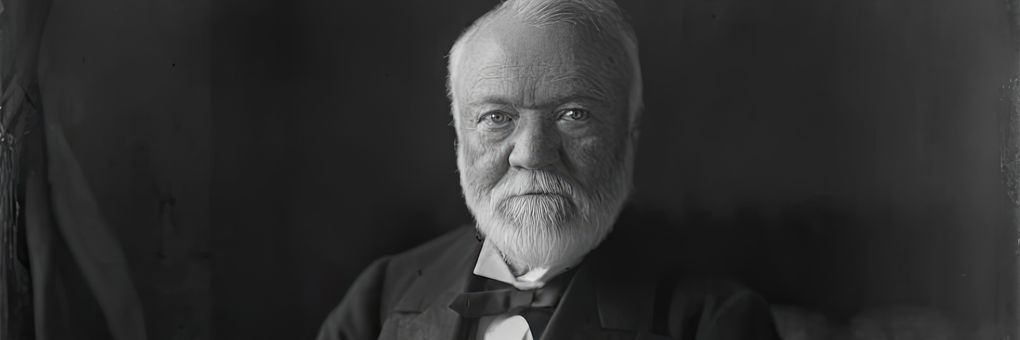

In a state famous for stupendous scenery, my view of the library lacks natural drama. It makes up for that with a sight rich in American history, a symbol of aspiration no less than the surrounding mountains. Opened in 1904, it is one of the hundreds of library buildings donated by the steel mogul Andrew Carnegie, the richest man in the world back then, who vowed to give away nearly as much money as he made.

His reasons for doing so lay in a working class childhood defined by poverty, and a fortune made at the expense of cheap labor and union busting.

For a deeper dive into the life of Andrew Carnegie, watch MagellanTV's “Andrew Carnegie: Rags to Riches.”

Carnegie’s Hard Work, Good Luck – and Insider Trading

Carnegie came to the United States with his destitute parents in 1848 at the age of 12. He died in 1919 after donating to many causes an amount equal to $65 billion today. He was not an inventor, like Thomas Edison, or a manufacturing and marketing innovator, like Henry Ford and George Eastman. Instead, his quick mind, focused work ethic, and the good luck to be at the right place at the right time, time after time, took him from messenger boy to the executive ranks of the high-tech businesses of 1850s America: telegraph and railroad companies.

Carnegie credited his success to books he borrowed as a teenager from the private library of a man concerned with the education of working boys in Carnegie’s new hometown, Allegheny, Pennsylvania.

Carnegie spent the Civil War as the civilian manager of the Union Army’s vital rail network. After the war, he benefited from insider stock purchases that today would be grossly illegal. He used the profits to make a substantial investment in a new industrial process that refined iron into steel.

Railroads, skyscrapers, bridges, battleships and cars, even housewares made of steel defined and symbolized America’s rising industrial power. For decades Carnegie controlled and profited from more than half of this colossal production.

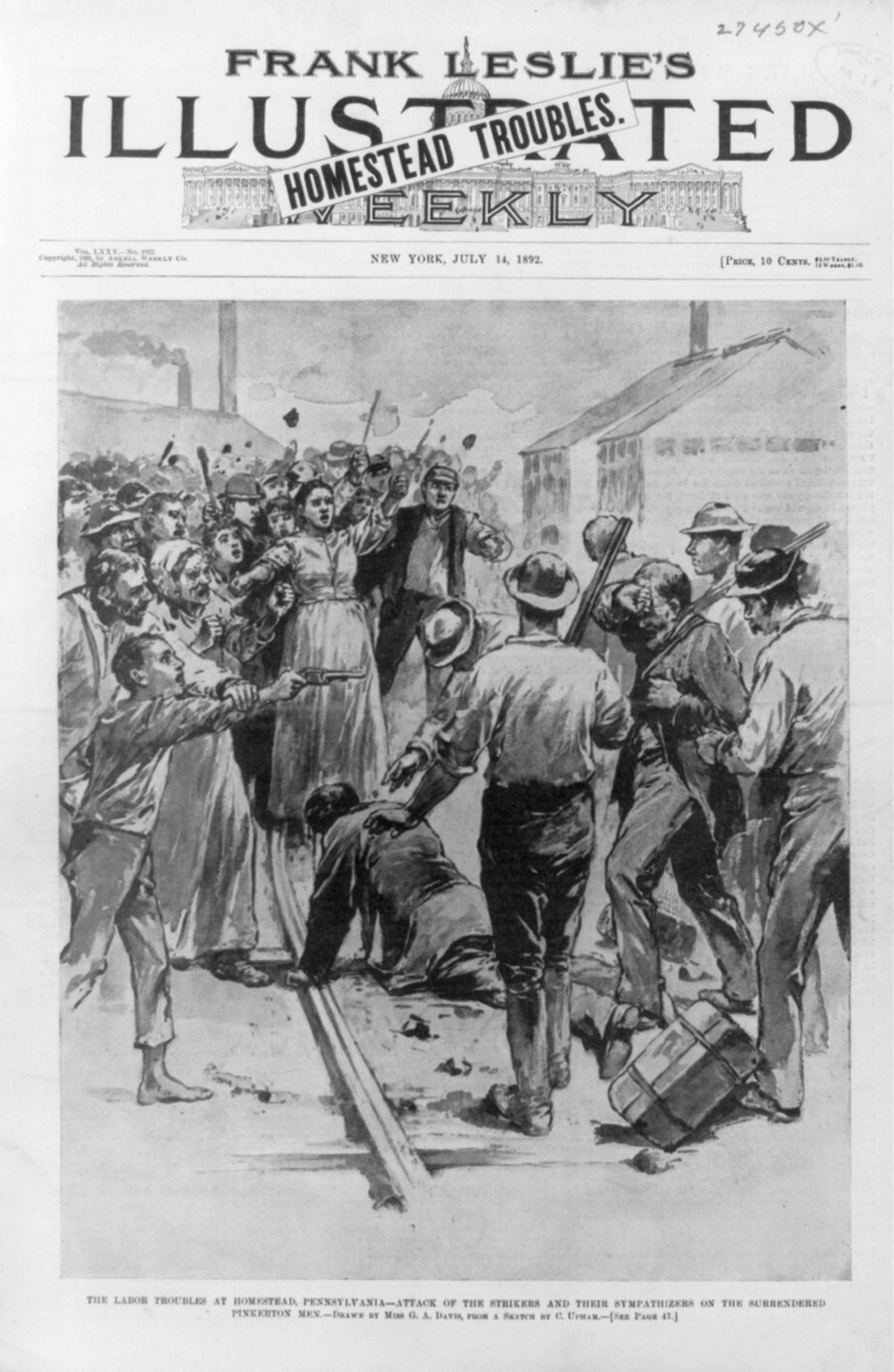

As his wealth accumulated, Carnegie, the son of a handloom weaver made penniless by machine textile production, became a dedicated foe of organized labor. He was ultimately responsible for the infamous, violent crushing of a strike at his Homestead, Pennsylvania, mill by Pinkerton agents in 1892, something that many never forgot or forgave.

The labor troubles at Homestead, Pa. - Attack of the strikers and their sympathizers on the surrendered Pinkerton men - drawn by Miss G.A. Davis, from a sketch by C. Upham, 1892

(Image courtesy of Library of Congress, via Wikimedia)

Why Carnegie Chose Libraries as His Mission

Carnegie saw the bettering of working people’s lives as a nearly sacred duty. Whether from religious conviction or guilty conscience, he firmly resolved to give away his fortune. His greatest priority was the cause of world peace. After that came the establishment of civic institutions across the English-speaking world, including concert venues (New York’s Carnegie Hall being the most famous), public baths, and, especially, libraries.

Carnegie put down his thoughts on philanthropy in an 1889 essay known as “The Gospel of Wealth.” In it he called upon the very rich to divest their assets for both the broader social good and the welfare of their immortal souls. “The man who dies thus rich,” he wrote, “dies disgraced.”

The library-building project got well underway in 1899. Before then, American public libraries were mainly located on the East Coast, housed in large downtown buildings many working people found intimidating to enter. There were very few neighborhood branches, and small-town libraries usually housed a small selection of books in a room at the City Hall, or as part of a general store.

Carnegie’s library program was managed by his executive assistant. It provided construction funds so long as the community would then contribute 10 percent of that cost annually to maintain the structure. So, a typical $10,000 grant required $1,000 yearly upkeep. To get a grant, towns first had to ask, prove a legitimate need, and show a building site. Once approved, the money was sent in thirds – the first at groundbreaking, the second once the foundation was laid, and the final payment on completion.

Because accepting a Carnegie library donation also involved a tax levy to pay local costs, the decision was usually put on the ballot. As women were often community leaders in library campaigns, many towns allowed them the opportunity to vote for the first time on this issue, decades before universal suffrage.

Carnegie’s library program ended upon his 1919 death. It created a total of 1,609 buildings in the U.S., over half of which are still operating. The grants effectively built New York City’s branch library system. Most of the other structures, 1,110, were located from Ohio to the Pacific coast (as well as a grand one in Honolulu, Hawai’i). The greatest number of grants (slightly over 200) were awarded in 1903.

His gift that year to the town where I live has been prized ever since.

Livingston, Montana’s Carnegie Public Library. (Credit: Picryl.com)

A Rowdy Western Railroad Town Gets Its Library

At the start of the 20th century, Livingston, Montana, was a Northern Pacific Railway town, with a big switching yard and locomotive shop. Once a raw Western settlement, a home to Calamity Jane, and gateway to Yellowstone Park, it was then in the process of rebuilding its business district, replacing wooden buildings and sidewalks with substantial brick and concrete commercial blocks and hotels.

Also, typically, Livingston was home to a population of single working men prone to leisure time distraction in saloons, pool halls, and other, more intimate, entertainment establishments. The town library consisted of two rented rooms behind a downtown storefront.

Desiring a more wholesome civic atmosphere, the town clerk wrote Carnegie’s office, saying he had “noticed from time to time that certain cities and towns [were granted] liberal donations for public libraries.” Replying to a request for more information, Livingston’s mayor wrote that a need was “very keenly felt [by the] large number of unmarried men who desired good books” as well as many young families. A grant of $10,000 was approved in March 1903.

The new library site was on a corner lot between downtown and the “respectable” residential district. The Iowa architect Charles Bell, fresh from his commission for Montana’s state capitol, was hired to design the edifice. (His next job was the capitol building of South Dakota.) He delivered a Classical-styled gem constructed of contemporary American materials.

Possibly because of the ill will many people felt toward Carnegie for his brutal, anti-union campaigns, only a third of the libraries he paid for carried his name on the outside.

Bell’s plans worked elegantly around the constraints imposed by a modest budget and remote locale. Decorative Doric pillars, along with the pediment they pretend to support, are wood, painted marble white. Sandy yellow bricks, cheaper than stone, nicely background the columns that appear to emerge from them. Above the arched entry are raised, gold-painted Roman numerals marking the year construction began, MDCCCCIII (1903). The pediment top above them frames smaller gold letters reading CARNEGIE LIBRARY.

The Livingston/Park County Carnegie Library in July 2020 (Image Credit: Joe Gioia)

The Library’s Symbolic Architecture

Bell’s tidy plan drew upon existing symbolism for library design intended to elevate, in many cases literally, civic welfare. Long front stairways represented the climb above everyday life to a world of learning and philosophy dwelling behind Classical temple columns. The doorway of every downtown building in Livingston (except the New Deal–era post office) is on street level. The Carnegie, however, sits on a man-made rise that accommodates twelve steps (for the Apostles? months of the year?) up from the sidewalk to its front entry. Inside, four more vestibule steps (the seasons? Evangelists? aces?) lead to the main floor.

Our Carnegie underwent a major, $1.3 million expansion in 2005 that more than doubled the interior and provided full handicap access. Like any modern library, it offers Internet, scanning, and printing services, DVDs, and audio books. Yet connections remain to its frontier past. Locals can, for example, still borrow the 1885 two-volume first edition of the Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, along with vintage westerns by Zane Grey, Max Brand, and Louis l’Amour. Also on the shelves are signed books by Montana authors Thomas McGuane, Jim Harrison, and James Welch.

The downside to the library’s corner lot is having to keep the long stretch of sidewalk around it clear of snow. When doing so, the head librarian and I talk about books, movies, certain writers, and some philosophy – his college major. He helped me understand deflationism, a way to test the truth of a statement. I filled him in on Henry James. In all seasons, most adults pass the library without much thought, but kids sense the building’s mythic design. After school, they climb to the narrow ledges between the pillars to sit or play. The boys sometimes grapple dramatically before jumping off; the girls might practice gymnastics or dance – young heroes on a classic stage.

Ω

Title image courtesy of Library of Congress

Contributing writer Joe Gioia is the author of The Guitar and the New World, a social history of American roots music. He lives in Livingston, Montana.