Mars, the Red Planet, has fascinated humans for as long as we’ve watched the stars. Its appeal is so great that even as science learned more about it, Mars became a realm of fanciful speculation, of engineering feats on a dying planet made by a civilization perhaps advanced enough to attack and colonize Earth. Humans are now the invaders of Mars, with sophisticated probes and fantastic plans to create a new planetary home.

◊

There was always something different about Mars. Early astronomers noted its reddish hue – the result we now know of a surface extremely rich in oxidized iron. Ancient observers, from China and India to Samaria, Egypt, and Greece, sensed something ominous in this wandering “star” tinged blood red.

The Greeks named it for Aries, their god of war. The Romans associated it with their war god, Mars, and dedicated a month of the year, March, to him. The Ides (the middle days of every Roman month) of March were especially ominous, as the bloody assassination of Julius Caesar on March 15, 44 BCE attested.

Nearly every culture linked the planet to conflict, anger, blood, and especially for the well-armed Greeks and Romans, battle. We should also note that, due to its pronounced elliptical orbit, which ranges between 128 and 155 million miles from Earth, the Red Planet appears to brighten, apparently in anger, before calming down. This pulse repeats every two years.

What’s more, Mars appeared to early skywatchers to reverse course in the night sky less frequently than any other “wandering star” (called planeton in Greek) – also about once every two years. This apparent retrograde motion indicates the period when the Earth’s orbit “catches up” with Mars’s wider circuit around the Sun. The two are at that time closest to one another, neck and neck, so to speak, in their cosmic race.

Mars Attracts!

The biannual periods of maximum brightness naturally attracted astronomers equipped with the first telescopes. Even at the dawn of the scientific age, Mars remained a source of awe and speculation. For some reason, the planet attracted more intense observation than Venus, the planet of love and peace, or Mercury, which represented the god of trade and communications.

Earth’s next close encounter with Mars will be during the first week of December 2022. After that, amateur astronomers will get the best view of the planet between January 12 and 16, 2025.

Where the 1500s had been the century of global exploration and mapping, the 1600s, which early-on saw the development of precision telescopes by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, very naturally brought this expansion of knowledge and measurement from the Earth to the heavens. We should not be surprised that those early astronomers were keen to find new lands and civilizations.

The past, present, and future of Mars exploration is presented in the fascinating MagellanTV documentary, Mars Calling 4K.

And we should keep in mind that those doing the speculating were among the leading astronomers of the day. Even as they produced solid scientific observations about our Solar System, many felt they also had found hard evidence of Martian life.

To Early Observers, Mars Looked a Lot Like Earth

In 1649, the Dutch polymath Christiaan Huygens produced the most sophisticated telescopes to that point. They were sensitive enough to resolve geographic features of Mars which Huygens then sketched, revealing what he called a vast “marsh.”

Around the time of Huygens’s initial discovery, Giovanni Cassini determined the length of the Martian day, only slightly longer than the Earth’s 24 hours. Both Cassini and Huygens noted what appeared to be the planet’s polar ice caps. In 1698, Huygens proposed the possibility of intelligent beings living on Mars.

The Cassini-Huygens spacecraft, a project between U.S. and European space agencies, was launched in 1997. It provided pictures and data from Venus and Jupiter on its way to Saturn. Once there, it dropped a lander on one of Saturn’s moons, and orbited the planet for 13 years before being sent on one last mission into its atmosphere in 2017.

In 1781, British astronomer William Herschel determined that Mars’s axial tilt was comparable to Earth’s, meaning that the planet experienced greater and lesser degrees of heat and cold on a seasonal basis very much like our own.

Based on these early observations, a working model of Martian conditions developed over the next century. As telescopes and other technologies became more sophisticated, Mars appeared more and more to resemble Earth. It was a planet with 24(ish) hour days, annual seasons, polar ice caps, and, thanks to early spectral analysis, an atmosphere with the likely presence of water. The possibility of intelligent Martians was hard to reject.

This notion was given further life in 1877 when Giovanni Schiaparelli produced the first richly detailed map of the planet. His chart, though absolutely accurate given the available technology, took the liberty of giving the names of Earth’s rivers to irregular lines that the Italian Schiaparelli called cannali. Though meaning “channels” in his native tongue, the word was mistranslated into English as “canals.”

A portion of Schiaparelli’s 1877 map of Mars (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Other broad observations seemed to indicate the presence of yellow clouds above a mostly desert landscape that underwent extreme day and night temperature shifts. Though a few scientists analyzing the spectral data proposed that Mars more closely resembled the barren Moon, and not Earth, academic speculation about Martian life took off, closely followed in the popular imagination.

It is probably not accidental that the excitement over Martian intelligent life began in the Age of Exploration and climaxed during the Age of Imperialism, which saw tremendous feats of European engineering, specifically the Suez and Panama canals, built on annexed foreign lands.

As 19th-century science was able to make closer, much more precise observations of the Moon, that satellite lost much of its mystery. It was no longer a reasonable place to discover alien beings and have adventures. Ironically, the more that was known about the Solar System, the more Mars became the focus of fanciful speculation.

A War with Mars? Maybe!

In the 18 years before the 1898 publication of The War of the Worlds, the classic novel about a Martian invasion by the early futurist H.G. Wells, at least eight adventure novels by other authors appeared featuring either visits to a civilized Mars or Martians journeying to Earth. The plot for Wells’s novel was in fact hung on advanced speculation about Martian conditions that mixed mostly legitimate data with what we now know was pure fantasy.

Those Martian canals, so the thinking went, were a civilization’s attempt to bring water from the polar ice caps to a dry, very likely dying, planet. In a neat reversal of the imperial project, what if, Wells proposed, an advanced Martian civilization left their doomed home planet to subjugate humans and colonize the Earth?

The canals of Mars, as sketched by astronomer Percival Lowell (Source: Wikipedia)

This fanciful scenario of an advanced civilization on a dying planet was popularized by the work of Percival Lowell, an American astronomer wealthy enough to commission the building of the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona in 1894. He was convinced he saw well-engineered water courses across the face of the planet and wrote three books on the subject between 1895 and 1908.

Lowell also launched the search for Pluto (then known as Planet X) based on its apparent gravitational effects on Uranus and Neptune. Lowell Observatory astronomer Clyde Tombaugh found Pluto in 1930, 14 years after Lowell’s death.

By the early 20th century, the notion of Martian canals, at least in astronomical circles, had been conclusively debunked – a matter of optical illusion and wishful thinking. The last great Martian adventure stories were written between 1912 and 1940 by master storyteller Edgar Rice Burroughs. He wrote nine novels set on Mars, called Barsoom by the natives, a desert world of strange creatures and tribal societies of sword-swinging warriors.

By the mid-20th century, with a few B-movie exceptions, Mars was no longer imagined as a place of advanced technological menace, or a realm of fantasy adventure. It had become instead an arid landscape waiting for human exploration and, turning the tables on H.G. Wells’s plot, a possible place of refuge from a ruined Earth.

This last proposition was articulated most famously in Ray Bradbury’s 1950 sci-fi classic The Martian Chronicles, the danger facing humanity though being 21st century nuclear annihilation, not environmental catastrophe.

The Martian Reality, and Fantastic New Plans

Three generations of space probes and mechanized exploration have given us an abidingly accurate, computer animated portrait of the Martian surface down to the smallest red rocky ridge. Once a planet with oceans and rivers, Mars apparently lost much of its atmosphere following a colossal asteroid collision over four billion years ago that also left an enormous dent in its surface.

The drastically-reduced atmosphere sent Mars’s water underground and allowed for a deadly bombardment of cosmic radiation. Temperatures range from about 95 degrees above to 225 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. Fierce dust storms and a toxic atmosphere add to a fundamentally inhospitable setting for any future human habitation.

Yet Mars remains the most Earth-like of our planetary neighbors, and still attracts us as a focus of interest, effort, and speculation. Plans for colonies there have been proposed and refined, along with designs for spacecraft able to get people there and back, for over 70 years. Included are ideas on how to recover its vast oceans and eventually produce an oxygen-rich atmosphere.

Somehow, the Red Planet, ancient symbol of conflict, conquest, and command, has drawn us into a new battle, not among ourselves, or versus alien invaders, but against a hostile and brutish environment still very much worthy of a god of war.

Ω

Contributing writer Joe Gioia edited and wrote for several long-gone photography magazines. He is the author of The Guitar and the New World, a history of American roots music, and lives in Livingston, Montana.

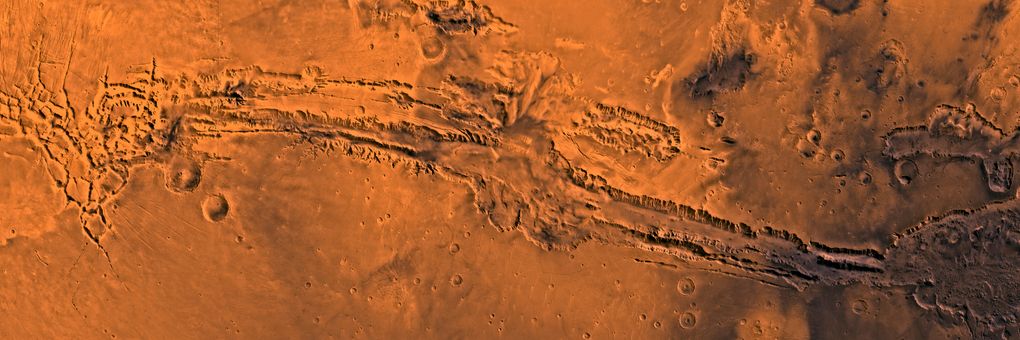

Title Image: The Valles Marineris, a Martian valley ten times longer and seven times deeper than the Grand Canyon – clearly NOT a canal. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/USGS, via Wikipedia)