Between 1933 and his suicide in 1945, Adolf Hitler embarked on audacious – and deadly – programs to establish Germany’s supremacy. But his unprecedented campaign of destruction and murder is not the focus here; rather, it’s his plans to remake – literally, to rebuild – his adopted homeland of Germany. In particular, he planned to establish Berlin, renamed as “Germania,” as the center of his thousand-year Third Reich. The Führer’s expansive fantasies of imperious, extravagantly scaled structures led directly to forced relocations and slave labor, resulting in, at minimum, tens of thousands of deaths.

◊

Young Adolph Hitler was on the run from Austria-Hungary’s military draft when he landed in Munich in 1913. And the 24-year-old would-be artist was virtually out of options. His failed attempts to gain entrance to the Vienna Academy of Art reduced him to selling hand-painted picture postcards to tourists. He even applied to the School of Architecture, but this attempt also came up short.

Fatefully, the advent of World War I, the “Great War,” profoundly changed Hitler’s ideas about military service, and, in 1914, he enlisted in the German Army’s infantry. Although his wartime experience was hardly exemplary, it was instructive. And only two decades later, he grabbed control of the German military and, within a shockingly few years, of German society as a whole.

It's clear, too, that Hitler never lost his fascination with architecture; nor did he shed his inflated self-image as a creator and maker of things. Once in power, he gathered around him a circle of sycophantic believers to institute his grandiose vision of an architecture that would anchor the Third Reich’s physical spaces.

Hitler elevated his architectural plans to the status of a primary directive of the Nazi administration, creating an Office of Construction to bring his many ideas to reality. He made sure that there would be no shortage of manpower, materials, and financial resources in the creation of an imperial architecture for the new Germany – an architecture rooted in the Führer’s admiration for the ideals and the conquests of the Roman Empire.

For an incisive view of Albert Speer and his complex relationship with Adolf Hitler, check out "Hitler's Architect," an episode of the MagellanTV documentary series, Last Secrets of the Third Reich.

The Führermuseum Introduces the Nazis’ ‘Starved’ New Classical Building Style

Hitler was obsessed with the Roman empire – its reach, its values, and seemingly, its size. The derivative style Hitler preferred for Nazi public buildings hewed close to its predecessors in the architecture of the Greek and Roman Classical eras. Nazi designs retained the grandeur of the earlier structures while stripping them of their many images of emperors, rulers, and gods and goddesses. With the decorative elements removed, the style has been called “starved neo-Classicism” by historians. Its designs became, in essence, tributes to the power of the state that created such out-of-scale monuments to the ego of the Führer himself.

Hitler appointed an architect – like himself, not a distinguished one – named Albert Speer to plan and oversee building construction in 1934, and then commenced a program as audacious as any since the great sprawling empires of the Classical Era. The newly minted Führer planned projects in numerous cities that came under his control.

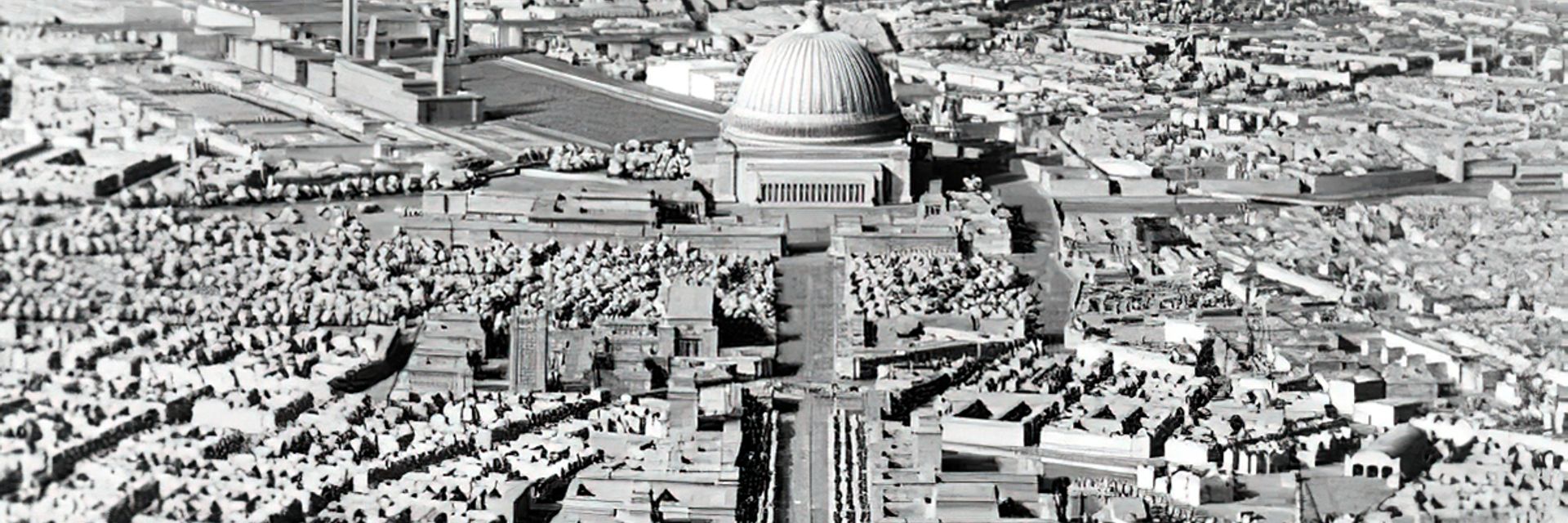

One such location was Linz, Austria, which he fondly regarded from his youth. Among the plans for that site was a massive Führermuseum, the jewel within a complex to be devoted to the mighty, mythic Aryan culture. Filling the museum depended on a massive plot to amass the world’s greatest collection of classical and neoclassical artworks through theft and plunder.

Model for unrealized Führermuseum, to have been located in Linz, Austria.

(Image Credit: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv)

As early as 1925, before he had ever visited Rome, Hitler produced a sketch for an imperial “palace of the people” that aped the design, while outdoing the scale of Rome’s Pantheon. He held onto that architectural rendering and gave it to Speer in 1934 as inspiration, if not clear direction, for Hitler’s grandiose vision of a Volkshalle (“hall of the people”) or Grosse Halle (“grand hall”).

Speer returned with a rendering for a building that had a seating capacity of 180,000, dwarfing any structure in existence at that time. It was to rise to a dome a height of 660 feet and width of 820 feet, making it 16 times larger than the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. In fact, the proposed oculus for this domed indoor arena, 151 feet in diameter, could have accommodated the Basilica’s dome being dropped through with plenty of room to spare.

In English, translating the Volks in Volkshalle as “of the people” hardly does justice to the racist undertones of the term. Die Volken, in context, has nationalistic undertones that imply racial exclusiveness, if not supremacy.

Also termed Speer’s Monsterbau, or monster-building, the structure was conceived to inspire, or even provoke, feelings of awe based on the majesty and outsize scale of the building to a human standing onsite. But rather than associating that awe with a spiritual or religious feeling, as Rome’s Pantheon did, this was instead intended to tie into the seemingly infinite power of the machinery of the Nazi state. Its proportion ran opposite to the values of humane, or human-scale, architecture.

The Oppressive Majesty of Germania’s Volkshalle, the Star of Hitler’s Nazi Dreams

This “people’s temple” to the master race was designed to be the central focus of what Hitler envisioned as the resurrection of Berlin. He wanted to herald the German city’s rebirth as a premier world capital of the “new order” for civilization, with the German people and their supposed Aryan heritage astride the apex of the rest of the subjugated world. This plan was called Welthauptstadt Germania, literally “Germania, world capital.”

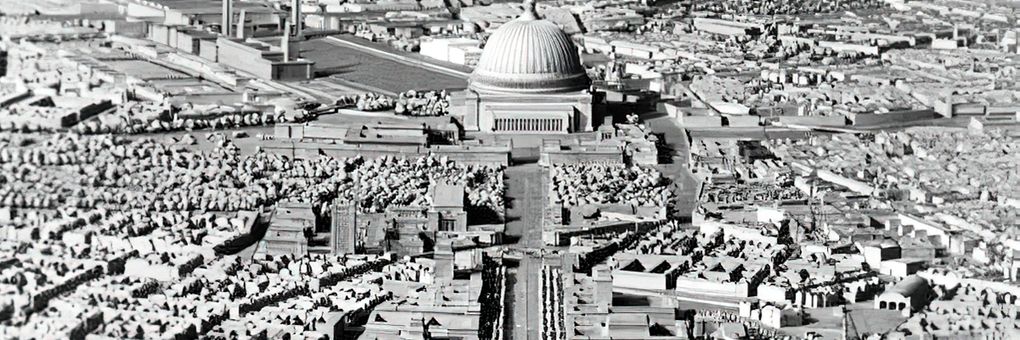

The massive urban renewal project was intended to replace a huge swath of Berlin from the ground up, with structures demolished block by block and neighborhood by neighborhood. Speer gladly ran with this grand plan to the point of constructing room-filling architectural scale models for his detail-obsessed boss. Hitler was said to have been so pleased with these models that he would spend hours crouched next to them, envisioning how the perspective of these grand structures would affect its imagined throngs of visitors.

Albert Speer’s plan for the Volkshalle was designed to dwarf every building around it.

(Image Credit: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv)

The massively imposing Volkshalle would be surrounded by broad avenues, a capacious plaza, and expansive areas for the display of 'people power' as well as military might. The coming of Germania would celebrate victory and lionize the leader who inspired the newly reborn city. And since, in Hitler’s mind, all cities of note had a symbolic structure to commemorate their victorious destinies, his city would build its own Triumphal Arch.

Speer’s father was also an architect, though not caught up in the madness of Nazism. When Albert proudly showed his father the plans for Germania, his father pronounced both architect and client crazy.

But, of course, this arch had to make all other arches look puny in comparison, so Speer was instructed to make it the biggest, most massive arch the ground could withstand. And so, after conducting tests to determine how much weight the ground could support without the foundation failing, Speer felt confident in planning a structure so enormous that France’s entire Arc de Triomphe could be positioned within the archway created by Speer’s design.

The bizarrely out-of-scale dimensions of the proposed German arch were designed to dwarf observers, even to make them feel insignificant against the expressed power of the Nazi state. But there was another purpose of this grand archway even closer to Hitler’s heart. It would also serve as a prominent memorial to the German war dead from the Great War that preceded the rise of the Third Reich. His intention was that the names of those servicemen all be inscribed on the walls of the arch. This would have transformed the story of that war from one of defeat to a more palatable one of glory and triumph.

Nuremberg's ‘Cathedral of Light’

Compared to the Nazi’s ambitions for it, the actual accomplishments of the Nazi building program under Speer’s direction are rather meager. They primarily include the “new” Reich Chancellery, built on an accelerated schedule in 1939-40, and one truly intriguing project, the Nuremberg airfield and parade grounds.

Captured most vividly in film-maker Leni Riefenstahl’s stunning piece of Nazi propaganda, The Triumph of the Will, the staging of the Nuremberg sites to enable Riefenstahl’s dramatic camera angles showed Speer’s prowess as a manipulator of light, space, and motion to create theatrical spectacles.

To add power to nighttime scenes, he pulled strings to get access to all of the German military’s anti-aircraft searchlights. Massing these in parallel vertical beams above the enormous crowds of military and civilians was a genius stroke. Called the “Cathedral of Light” for its celestial associations, Speer used similar lighting arrangements in numerous night rallies around the country, wherever he could amass enough light and power.

Speer used military searchlights to illuminate the parade grounds in Nuremberg and elsewhere around Germany.

(Image Credit: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv)

Considering his lack of lasting portfolio, Speer’s bit of trickery with light manipulation is perhaps his most lasting achievement. Contingent, transparent, ephemeral yet spectacular, maybe this is a metaphor for the failed dreams of the delusional Nazi state.

The Cost, Both in Human Blood and in Treasure

To prepare the way for the planned Germania, thousands of acres of prime, high-density, urban real estate had to be cleared. Typically, Hitler was unconcerned about the cost, both to his treasury and to human life. To him, the Nazi building project was of equal importance to the war he had brought crashing down upon Europe. The latter would allow Germany to avenge its loss in the Great War; the former would assure its future glory as the world’s dominant power.

The program for transforming Berlin into Germania started with relocations. Thousands of city residents had to be separated from their property and removed from their homes. Social rank and influence guided the process, with upper-class residents taking over middle-class Jewish homes, while Jews themselves were marked with yellow stars of David and corralled into ghettos and concentration camps.

Albert Speer worked closely with Adolf Hitler on many projects related both to construction and destruction.

(Image Credit: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv)

At the program’s height in the late 1930s, lower class Berliners were utilized to beef up the ranks of prisoners sentenced to hard labor. Quarries and brick manufacturing plants were opened close to the forced labor camps, and another 130,000 prisoners worked at demolition sites where land was being cleared for the construction of Germania. The labor was brutal, beyond hard, and many of the prisoners were literally worked to death.

Only a few years later, the course of the war turned against Hitler, and that reality undermined his maniacal plans to create a sparkling, faux-Classical city of his fevered dreams to redeem the catastrophic defeat of the Great War – and to sate the appetite of his monstrous ego. Germany’s once-invincible armies fell back, losing battle after battle. It’s cities, bombed from above, collapsed into rubble. Berlin lay in ruins.

No Aryan Germania would rise from the flames. Hitler, who fancied himself a creator of art, of architecture, of empire, huddled in the secret Führerbunker Speer had prepared for him beneath Berlin’s chancellery grounds. The rumble of explosions above and around his lair was incessant. The Nazi program to rebuild the city – and, indeed, the world – according to his delusional fantasies was over. As Russian soldiers closed in on his hideaway, he put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger.

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image Credit: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv