A universal social practice, music has long been understood to have mysterious properties that can, as needed, help energize, calm, and heal troubled bodies and minds. While music’s therapeutic benefits have been used in medical settings since the 1940s, it wasn’t until the development of light-weight fMRI scanning in the early ’90s that researchers were able to watch in real time what melody and rhythm do to the human brain. The volume and density of neural engagement astounded them. Music is literally an integrating collective phenomenon that, more than any other activity, defines what it means to be human.

◊

One morning in late 1964, a 22-year-old Paul McCartney awoke with a tune in his head. It was lovely, and, sitting at his piano sounding it out, he was pretty sure he was only remembering something written by somebody else.

After playing it for the other Beatles and assorted friends, he eventually realized that the dream melody was his alone. After a little more work, and with lyrics added, it became “Yesterday,” one of the most recorded songs in history.

Something might have been in the air back then, because around the time “Yesterday” was hitting the pop charts, The Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards woke up one morning (or maybe it was the afternoon) and noticed his cassette tape recorder had been switched on overnight. He had apparently awakened, hit “record,” and played a three-note riff on his handy acoustic guitar. He had also mumbled “I can’t get no satisfaction” into the microphone before falling back to sleep.

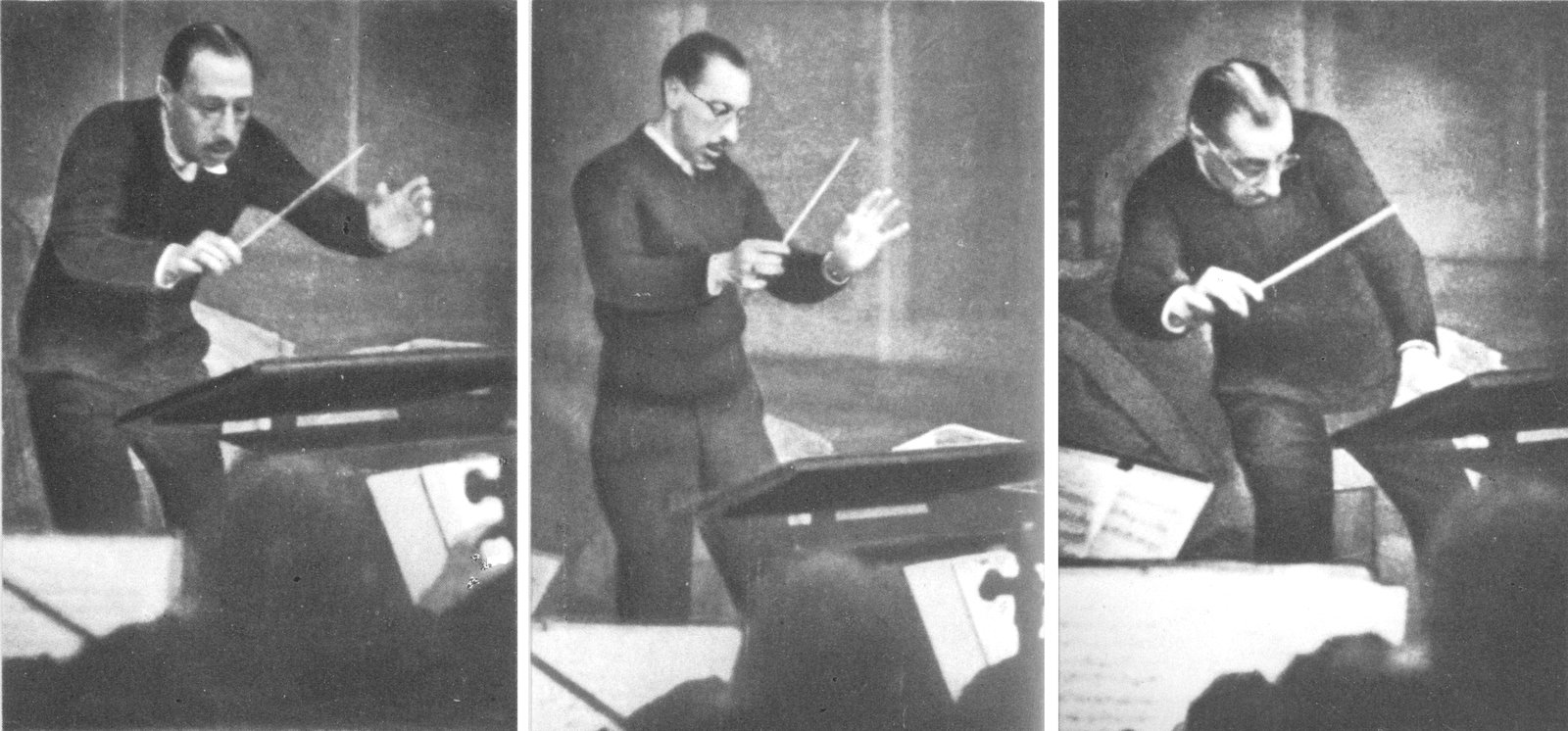

Two dreams, two colossal hit songs. While amazing, in the history of classical music, composing while asleep is apparently common enough. Handel, Mozart, Chopin, Brahms, Stravinsky, and Ravel all spoke of receiving music in dreams. While the stone deaf Beethoven may or may not have composed in his sleep, he certainly could “hear” complex music deep in his mind.

Igor Stravinsky was just one composer who said he drew music from his dreams.

(Image Credit: F. Man, via Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, all of the composers mentioned above are geniuses. It may be that they benefited from innate abilities far beyond those allowed the average person. But sometimes things happen to people – shocks or head injuries that appear to unlock unexpected, and unprecedented, musical ability.

Music’s Neural Depths

The late neurologist and author Oliver Sacks wrote of a fascinating case in his book Musicophilia, a collection of essays on how music affects the brain. A 42-year-old doctor was struck by lightning at a picnic and would have died without prompt CPR. Two months following his ordeal, Sacks reports, the doctor was otherwise fine, except for one big change: He felt an overwhelming urge to listen to classical piano music.

Buying a shelf of records was not enough. The man then got a piano and bought sheet music. Though he’d had a few piano lessons as a child, he essentially taught himself to play, eventually reaching an advanced amateur level. He told Sacks he also “heard” music in a never-ending stream in his head and began to transcribe what came to him.

While most of us are familiar with an interior monologue, a stream of impressions and thoughts that mainly manifests in a verbal way, this inner process can be experienced by some people as complex varieties of tones and rhythms. Medical researchers have come to recognize that a capacity for musical expression exists in almost everyone, encoded in diverse areas of the brain unrecognized until very recently.

A grasp of music and rhythm has been revealed to reside in our brains on a level at least as fundamental as language, and is perhaps even more essential. This new understanding of the neurological depth and breadth of music holds tremendous implications for the treatment of an array of disorders, from Alzheimer’s to heart disease.

Though the healing power of music has been a feature of nearly every human culture from the dawn of time, it received little scientific attention until the Second World War, during which musical performances at Army hospitals showed significant positive results among severely “shellshocked,” what’s now termed PTSD, patients.

What is Music Therapy?

Codified as a therapeutic practice in the 1950s, music therapy employs several related processes to engage patients with a range of neurological, physical, and emotional disorders. From simply listening to recordings, attending live performances, and group singing, to songwriting sessions, drumming groups, and dancing, the broad umbrella of treatments have been found effective in calming the nervous system, processing emotions, re-patterning brain circuitry, and inducing movement in injured or stressed muscles.

Though not a cure, music therapy has been found very effective in treating anxiety and eating disorders, symptoms of dementia, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s Disease, as well as being useful in grief counseling, comforting premature infants, even regulating high blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory problems.

Though music therapy has been an accepted form of mental health treatment since the 1950s, it wasn’t until the development of wearable fMRI brain scanning equipment in the early 1990s that researchers were able to see in real time what was happening when people listen to music. The findings were astonishing.

Rather than activating limited parts of the brain as did other particular activities such as speech, memory recall, or muscle movement, experiencing music enlivened diverse areas in both the left and right hemispheres. Areas of the brain responsible for emotion, memory, movement, language, even regulating blood pressure, all fired at once. So next time you hear a favorite tune that gets you tapping your foot and singing along, just know that your brain is getting a better workout than from nearly any other activity.

In fact, the only thing better for your head than listening to music is playing it. Once researchers were able to fit fMRI sensors onto musicians in the act of performing, the full impact of music on the brain became dazzlingly apparent.

fMRI image of the several brain regions activated by listening to music. (Image Credit: "How music touches the brain," in sciencenordic.com)

This Is Your Brain on Music

If listening to music can be compared to street lights illuminating several dark city blocks, playing music is the mind’s equivalent to switching on Times Square. The nearly total engagement of the two halves of the brain needed to learn and play an instrument may be the reason why the corpus callosum, that part of the brain connecting both halves, is noticeably larger in musicians.

Brain areas integrating music appreciation include the temporal lobe that processes tones, the cerebellum that handles rhythm and limb movement, while emotions and memories are regulated and retrieved through the hippocampus and amygdala regions.

Though an aptitude for music certainly runs in families, and is likely the result of a genetic “gift” of enhanced neural relays, there is no question that the motor and memory skills needed to learn an instrument, coupled with the reservoirs of feeling and expression music performance entails, builds crucial connections in the brain that manifest on a physical level. Sacks notes that “Anatomists today would be hard put to identify the brain of a visual artist, a writer, or a mathematician – but they could recognize the brain of a professional musician without a moment’s hesitation.”

This total brain workout is why music therapy has proved so effective. By activating several different areas at once, music actually helps “rewire” damaged or inhibited portions to create new neural pathways for memories, emotions, and motor skills.

Though it’s tempting to think that highly structured music, such as a Bach fugue, is better for the brain than, say, listening to Elvis Presley croon “Heartbreak Hotel,” the plain fact is that every type of music energizes brain function, at least for as long as it’s playing.

Sadly, an estimated five percent of the population has what’s termed Amusia, that is, no ability whatsoever to appreciate music. One famous sufferer was President Ulysses S. Grant, who admitted: “I know two tunes. One of them is ‘Yankee Doodle,’ the other isn’t.”

In the wake of the fMRI findings in the early ’90s, there was a popular misconception that playing musically complex compositions, such as Mozart symphonies, for sleeping infants would have positive long-term effects on the children’s intelligence. Alas, this was an optimistic reading of the data. While there are undeniable cognitive benefits to studying and playing music, even gifted players need to put in hours of difficult practice to reap the long-term neurological benefits offered by music.

Egyptian lute players are pictured on a tomb fresco, ca. 1800 B.C.E. (Image Credit: wikicommons)

Music As the Essential Human Condition

Thankfully, a capacity to respond to and play music is not at all connected to standard measures of intelligence or brain capacity. Medical literature abounds in case histories of people with severely diminished mental faculties due to illness, injury, or birth defect who still abound in musical ability. In Musicophilia, Sacks reports on several Alzheimer’s patients, professional musicians before becoming ill, who fully retain their musical skills and understanding even as the illness has otherwise wiped away their memories and grasp of everyday life.

Sacks also writes about individuals with the condition known as Williams Syndrome, a severe birth defect that can produce pronounced musical aptitude in outgoing, highly social individuals who otherwise require no small level of care to help negotiate the routine demands of life. Affected individuals thrive in group settings where they can play music both with themselves and conventionally talented musicians.

Examples like these point to a profound and enduring capacity to process and perform music unrelated to cognitive capacity. Because of this, some now consider musical response to be a fundamental definition of what it means to be human. While close, long-term study of the behavior of primates and other highly functioning vertebrates has found examples of basic voiced communication, tool use, problem solving, and self-identity, what has not been observed among even our closest ape cousins are coordinated patterns of communal music making and dance.

There is now a school of thought proposing this essential and exclusively human process is something that evolved before the advent of language – that early humans first communicated by vocalizing song before developing the capacity for speech. Closely connected to an awareness of time, it appears that the ability to make and respond to music might be the defining characteristic that separates humans from the rest of life on Earth.

Buried deeply throughout the recesses of the human brain, the ability to create and respond to music is a shared characteristic that unites every culture on the planet. This means that if everybody is really going to get along, we need to do much less talking and lots more singing.

Ω

Title Image Credit: Wikicommons