Working on the Moon was no walk in the park for the Apollo astronauts. But they kept working, overcame the obstacles, and succeeded in making history.

◊

“No single space project in this period will be more impressive …

and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish."

President John F. Kennedy, May 25th, 1961

Watching the Apollo astronauts bounce around the Moon and listening to their easy banter with CAPCOM in Houston, you could be forgiven for thinking each lunar landing mission was “a walk in the park.” But it wasn’t. Not one of them.

MagellanTV’s original documentary, Apollo’s New Moon, chronicles how the crews gathered the hard evidence that would completely overturn our understanding of the Solar System’s birth. Those twelve moon-walking astronauts – and their six orbiting pilots – embodied the tough, cool reserve expected of NASA personnel. They seldom complained. They only joked about discomfort. But each was juggling several perilous challenges at every moment, not least of which was simply getting around in the space suit.

Resistance Is Futile: Space Suits on the Moon

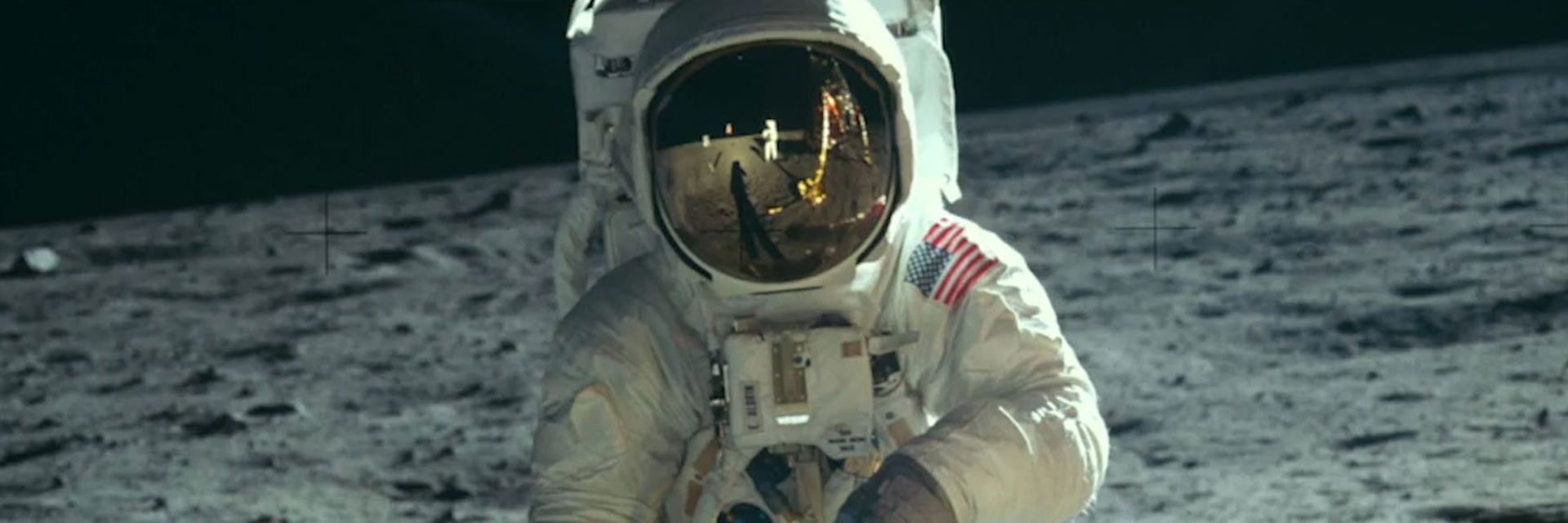

Made less flexible by the very air pressure needed to survive, it was awkward to bend the suit’s elbows, knees, and waist. Silicone rubber-tipped gloves, made of metal fabric, limited manual dexterity and prevented all but the most gross approximations of touch. The helmet faced only forward, restricting vision up and down and from side-to-side. “Alligator head,” the astronauts called it. More than one pulled loose vital cables because they simply couldn’t see their feet.

Apollo astronaut, Buzz Aldrin, on the moon.

(Image courtesy of NASA, via Wikimedia)

Even on the Moon, gravity wants to topple you over. The Portable Life Support System (PLSS) backpacks, combined with their emergency Oxygen Purge Systems (OPS), weighed 58 kg (127lbs) on Earth. So much mass, up high, made astronauts lean forward, constantly counterbalancing. They sometimes stumbled under the awkward weight. Occasionally, they actually fell down, especially when exerting force on a tool. Or while trying to dance around the wires connecting experiments.

When they tumbled, they had to invent ways to get upright. As you can see in Apollo’s New Moon, this sometimes meant bouncing back and forth between knees and hands to build inertia, until they bounded high enough to swing their feet under their centers of mass.

Apollo 16’s Charlie Duke – the youngest moon-walker – said the only moment of panic he had on his entire moon-trip was when falling. With most of their task objectives complete, Duke and crewmate John Young were, in true test pilot fashion, pushing the envelope; competing to see how high they could jump in the low gravity. Duke shot up but began to arc over onto his back. The slow-motion trajectory gave him time to think dark thoughts: Visions of smashed life-support plumbing filled his head. Depressurize your suit and you’re dead, he thought. Instinct made him drop one shoulder and roll to his right, protecting vital suit systems just in time. Had Duke landed on his back, even if the pumps and regulators and piping held together, he might have needed Young’s help to stand.

Time Keeps on Ticking: The Packed Work Schedule of Apollo Astronauts

Always the moon-walkers felt the pressure of the clock. Each crew-member was carefully selected and highly trained to execute the task load without bitching. Apollo transcripts are (mostly) clean of cursing. But that doesn’t mean they didn’t bite their tongues a lot.

Listening to Apollo 11’s communications from the lunar surface, you may get the feeling Neil Armstrong was a man of few words. While that is a fair description of his personality, the fact is he was very busy! Though given only minimal training in geology, Armstrong set a very high bar for accurate and significant scientific sample collection – but only by improvising on the fly.

It had been Mission Control’s desire to keep a close eye on the crew through a slow-scan TV downlink. Armstrong, however, noticed terrains and individual rocks that differed from those in the immediate landing area. He had no time to reposition the TV camera. He wasn’t reckless but, to get better science, Armstrong ventured beyond view for more than seven nervous Houston minutes.

Buzz Aldrin had his own challenge: deploying the complex and massive Early Apollo Scientific Experiment Package (EASEP). All that should have been needed was to set it down on the flat ground. Trouble was, there wasn’t any. For many minutes, Buzz couldn’t get the small level indictor to settle down and center up. He doesn’t know how it happened, but when he and Neil came back a few minutes later, the EASEP was perfectly level.

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin

(Images courtesy of NASA, via Wikimedia)

Watching that downlink of the Apollo 11 surface EVA (extra-vehicular activity), you can feel their tempo pick up. They were hustling to make the timeline. Houston had budgeted two hours and twenty minutes of “stay-time.” But, just eight minutes from the planned end, Neil still had not acquired the all-important “Documented Sample” of lunar soil. This job required him to photograph carefully, then make notes of the specific context of, several scoops of material as he maneuvered them into pre-numbered bags. Tick, tick, tick . . .

A recent Georgia Tech study found that every Apollo lunar EVA ran longer than planned, except one. And that one, Apollo 15’s first sortie, was behind schedule for almost all of its timeline. Astronauts used much more of their suits’ consumables – like oxygen and water – than was thought likely. Georgia Tech found cases where they were up to 20% “in the red.”

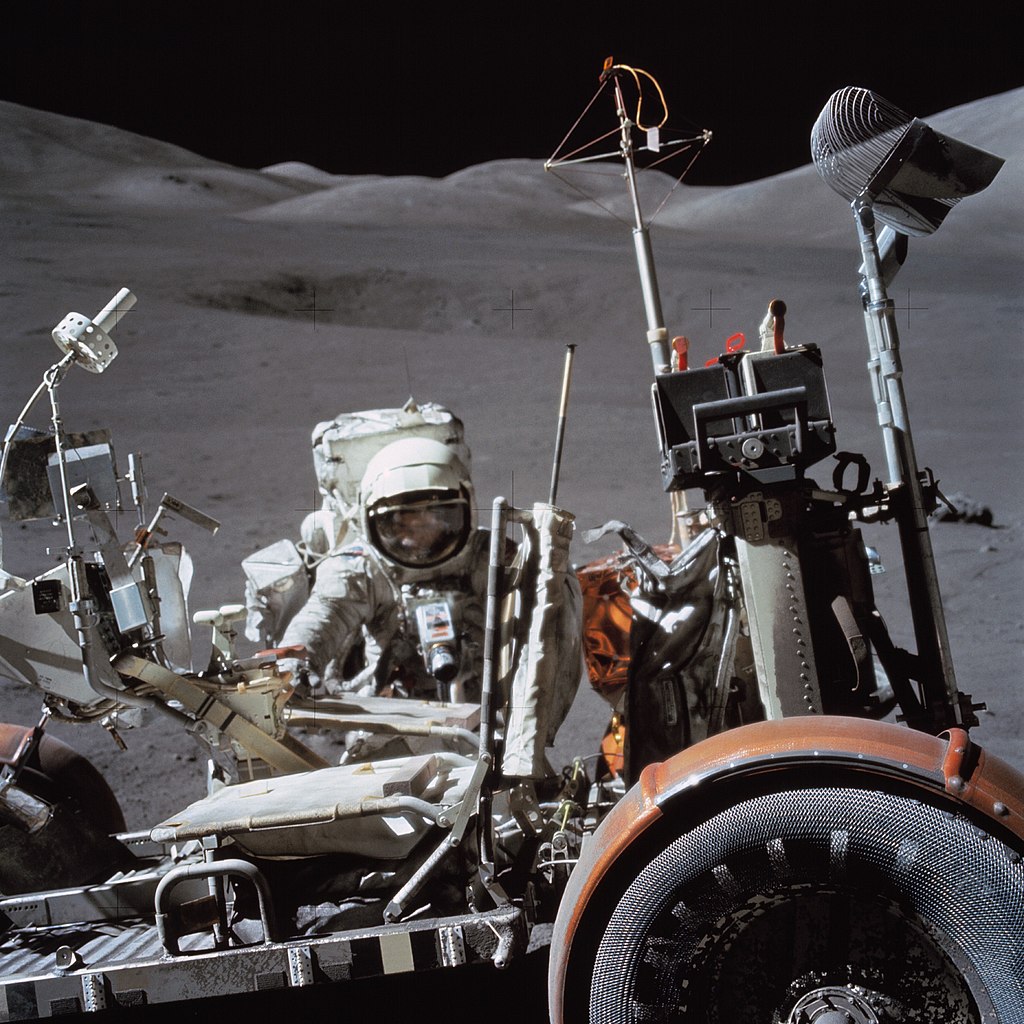

The “time-bandit” throughout all of Apollo turned out to be simple movement from site to site. Whether on foot, or in the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV), it took longer for astronauts to navigate and arrive on station than anyone predicted. This despite each mission’s contribution to refining the learning process.

The Lunar Roving Vehicle.

(Image courtesy of NASA/David R. Scott, via Wikimedia)

In the future, operating on the lunar far-side – or out at the time-delay of Mars – will put surface astronauts out of touch of Earth-bound managers. Choreography will have to be managed by the dancers themselves. Space enterprises of the future take heed: On alien worlds, stuff takes longer!

Sunshine on My Shoulder: The Sun’s Impact on Lunar Surface Conditions

It’s always a sunny day on the Moon. Even with slide rules and pencils, it was possible for Apollo planners to accurately predict the angle of sunlight for every mission. Each was timed to put the Sun low in the East. Why? Because long shadows made it easier to determine the relative height of objects on this utterly alien landscape. But those shadows created other problems.

Apollo 16’s Charlie Duke was the only moon-walker to comment on the heat of the Sun during any mission: ”Boy, it’s hot out here today!” With the higher angle of sunlight, he and Young had to turn the suit-cooling system up to its higher-than-normal Intermediate setting.

With no atmosphere to moderate temperatures, moving gear between the hot sunlit areas and the cold shadows caused a few malfunctions with cameras, a Cosmic Ray detector, and one Surface Electric Properties experiment. But excellent planning and diligent attention by the astronauts kept most thermal issues at bay.

Click the image to stream now!

While all the Apollo missions landed relatively close to the Moon’s equator, operating near a lunar pole – NASA’s next destination – will present additional challenges. And some advantages, too: for example, the ability to collect solar energy from peaks that are always lit, while also being able to utilize the largest reserves of water-ice from nearby valleys that have never seen the Sun.

“Rad-Hot” Hazards of Traveling to and Working on the Moon

For Apollo astronauts and their gear, a bigger risk from the Sun was radiation. With no protective magnetic field or atmosphere, the Moon gets the full brunt of incoming solar energetic particles (SEP). If a large solar flare or coronal mass ejection (CME) had occurred during any of the Apollo missions, the effects could have been deadly. During the Apollo program, only one such event happened, and it fell, fortunately, on August 4, 1972, right between Apollo 16 and 17.

Even just flying in an airplane over Earth’s poles puts you in increased danger of “rads.” Coming from – and going to – the Moon dramatically ratchets up that risk. About ten hours out from Earth (at ~4.5 Earth radii), our planet’s magnetic field traps high energy particles. This keeps them from hitting the ground, but it presents a hot-zone for transiting astronauts to cross. The faster they pass through, the less dose they get. But then the spacecraft must bleed off all that speed to make landings, which means using a lot of propellent to counter Earth’s gravitational pull.

If we expect people to live on the Moon, we’ll need to give them shelters from Galactic Cosmic Rays and SEPs. Burrowing a meter or more under lunar soil should do nicely. But workers and explorers – and eventually vacationers – must be willing to accept the ever-present risk of being caught out in the open, with nothing between them and the angry universe.

A Fall of Moon-Dust

If you compare images of astronauts starting out their first moon-walk to pictures taken toward the end of that EVA, you’ll immediately see it: The Moon is a dirty place!

Meteors – from huge asteroids to microscopic flakes – have been impacting the lunar surface for 4.5 billion years. As a result, the surface has been pulverized to a fine powder. If you’ve baked at home with milled flour or 10x confectioners’ sugar, you know the approximate consistency of lunar soil. It’s just as clingy, but it’s dark and sooty. Buzz Aldrin described it as “a grayish-cocoa color.” But don’t try to make tea with it; moon-dust is toxic! Apollo 17’s Jack Schmitt had a sneezing fit when he doffed his space suit inside the Landing Module.

Jack Schmitt (Image courtesy of Project Apollo Archive, via Wikimedia)

And all that dust seems to want to go everywhere and get into everything. As you watch John Young drive across the Moon, you see sprays of soil arcing off the rover’s wheels. Astronauts had to stop what they were doing frequently, get out a brush, and clean lenses – including the live TV camera, which noticeably improved the images seen all around Earth.

Aldrin – and, in fact most of the moon-walkers – noted that once back inside the pressurized LM, the soil on their suits and sample bags had the scent of spent gunpowder. Jack Schmitt believes this aroma to be the product of electrons in moon-minerals reacting with oxygen in the cabin, just like what happens in a freshly fired firecracker, or a gun barrel.

The last Apollo moon-walker, Gene Cernan, entered the LM looking like a coal miner. His appearance was, perhaps, prophetic: The next generation of moon-walkers are likely to be miners; not of carbon, but of hydrogen and oxygen.

Sleeping on the Moon

Sometimes, it’s the little things. None of the 12 Apollo astronauts slept very comfortably on the Moon. The possible reasons for the sleep deprivation are many: Maybe it was the unfamiliar “partial” gravity, after traveling several days to get there in weightless conditions. Perhaps the lack of a sunset or noises from a glycol pump and other machinery inside the Lunar Module. Occasional radio crackle and cold temperatures didn’t help. Not to mention close quarters filled with gear and funky hammock-hanging arrangements (which Apollo 11’s crew didn’t even have).

The first three crews had the added challenge of being required to stay in their EVA suits. Apollo 14’s Alan Shepard and Ed Mitchell may have had the worst experience: They hadn’t gotten good sleep on the trip out to the Moon, and they’d landed on sloped terrain and couldn’t shake the feeling the LM might tip over.

.jpg)

Apollo 14 (Image courtesy of Project Apollo Archive, via Wikimedia)

Apollo 15’s Dave Scott and Jim Irwin got to try sleeping in just their cooling underwear. But even the light tug of lunar gravity pushed lumpy liquid tubes up against their skin. Apollo 16’s John Young simply took his off, and got the best rest yet.

We can imagine each crewmember lying awake, feeling the emotional weight of the mission, reciting the “astronaut’s prayer”: “Please, Lord, let me not screw up tomorrow.”

Looking Back to See the Way Forward

As Project Apollo recedes in the rear-view mirror, it’s easy to lose sight of what’s important.

Wasn’t it just a political stunt? A marketing-move by a shrewd young President to prove American supremacy? An expensive warning shot to demonstrate that the United States could catch up and surpass any challenger? A clandestine strategy to keep together a network of military contractors, seeding their payrolls through Cold War downtimes?

It may have been all of those. But, from a half-century on, we can see that the most valuable work Project Apollo did was actually just the simple collection of samples. Thanks to the moon-walkers’ disciplined field geology – and the painstaking science analysis that followed – we now understand how the Solar System was built, how Earth formed, and what lies waiting for us on the Moon should we choose to go back.

A lot of additional hard moon-work will be needed to extract and process all that Earth’s one natural satellite has to offer humanity. But, because of what those first Apollo prospectors did fifty years ago, under truly death-defying circumstances, we now have a good idea what to do next.

Title image courtesy of NASA, via Wikimedia.