LSD, psilocybin, ketamine, DMT: These psychedelic drugs might be associated with hard-partying deviant or hippie types, but recent research has found that they might be formidable treatments for chronic and challenging mental illnesses. To better understand how these effects are possible, we’ll explore how these drugs actually work in the brain while also traversing some of the most fascinating research and stories about their complex histories and immense potential.

◊

On April 19, 1943, Albert Hoffman rode his bicycle home from his laboratory. Already seeing strange images and odd kaleidoscopic effects, Hoffman was panicking by the time he arrived at home. “Everything in the room spun around, and the familiar objects and pieces of furniture assumed grotesque, threatening forms,” he said of his experience. “They were in continuous motion, animated, as if driven by an inner restlessness.”

Hoffman dosed himself with 250 micrograms of a chemical called lysergic acid diethylamide-25, which would become known as LSD. Hoffman thought the substance might treat respiratory and circulatory issues, but what happened was much stranger. This was actually the second time he (or anyone else in the world) ever took the drug; he took the first dose three days before, on April 16, when he tried a substance he had synthesized from a fungus called ergot.

But that day on his bicycle, Hoffman was terrified. Eventually, with the help of his assistant, he was able to relax. “Now, little by little I could begin to enjoy the unprecedented colors and plays of shapes that persisted behind my closed eyes,” he recalled. The morning after, he awoke with a renewed sense of wonder and vigor.

Over the coming decades, LSD would become more widely popular than Hoffman could’ve ever expected. Like many other hallucinogenic drugs, it would be feared, condemned, and even blacklisted; for 70 years, academic research on them was completely banned. Lately, though, psychedelics have emerged at the forefront of medical innovation as a potential miracle cure for complex mental illnesses.

How LSD Works In The Brain

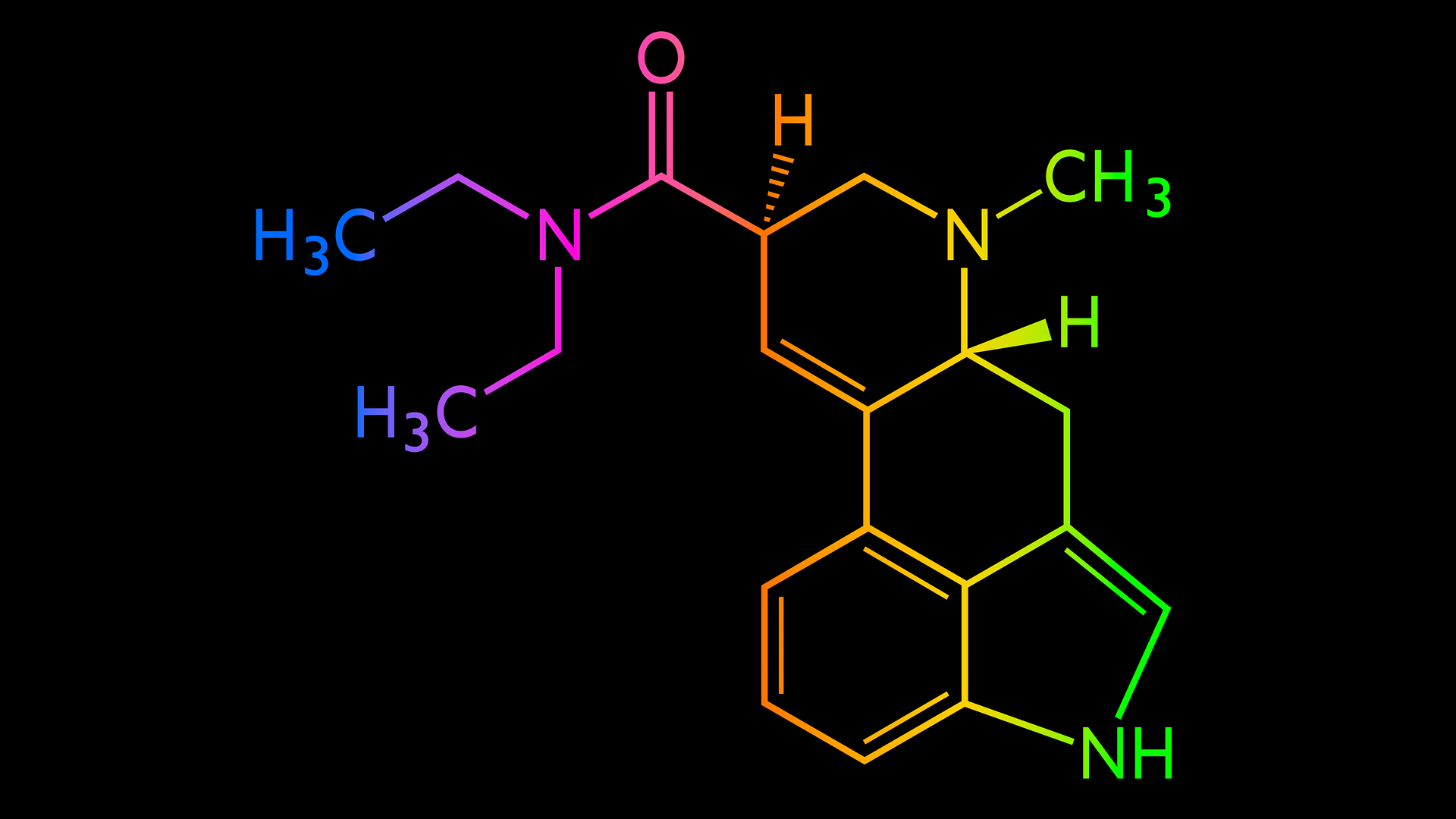

The majority of psychedelic drugs – LSD included – achieve their effects by interacting with serotonin, a protein that lies on the surface of brain cells and helps them communicate.

A study by David Wacker and colleagues at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, found that when LSD binds to a receptor in the brain that typically detects serotonin, the receptor closes around the LSD molecule, trapping it inside. This might explain the extended length of LSD experiences, commonly known as trips, and it also indicates that even trace amounts of the drug can influence the brain.

Chemical structure of LSD-25 (Credit: Colin Behrens, via Pixabay)

So what happens when LSD binds to that receptor? While everyone’s experience is different, there are some common themes. People on LSD often report a feeling of ego death, or losing their sense of self, and frequently also experience shifts in long-standing beliefs. Sometimes these experiences can be positive, leading people to feel a deeper sense of connection to each other, to nature, or to spirituality, while other times they can be negative, causing people to question the meaning of their life or the nature of their reality.

“We observed brain changes under LSD that suggested our volunteers were ‘seeing with their eyes shut’ – albeit they were seeing things from their imagination rather than from the outside world. We saw that many more areas of the brain than normal were contributing to visual processing under LSD.” – Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris

The “ego-dissolution” that occurs during acid trips is connected to how LSD dissolves the default mode network (DMN), which is the structure of communication that our brain uses to process information and control consciousness. The DMN’s disappearance allows for increased communication between parts of the brain that are often disconnected, and this can lead to a feeling of increased interconnectedness and to a dissolution of the ego.

It can also lead to a lot of other wild experiences and sensations. Without the DMN, parts of the brain that are typically not involved with vision are suddenly allowed to contribute to the brain’s perception of visual reality, which can lead to the hallucinogenic visions that trippers often experience.

Expanded Consciousness: The Science of Mushrooms

Another popular hallucinogenic drug is psilocybin, an ingredient found in certain mushrooms (often referred to as “magic mushrooms” or “shrooms”). Around 180 different species of mushrooms produce psilocybin.

Psilocibyn mushrooms (Credit: TherapeuticShroom, via Pixabay)

Ethnobotanist Terence McKenna’s intriguing “stoned ape theory” proposes that psychedelic fungi may have been integral to the origins of human consciousness. Around 40,000 years ago, a so-called “creative explosion” occurred in homo sapiens, sparking a massive leap in cognitive abilities. Suddenly, early humans were able to reflect on life, but the catalyst for this change remains a mystery. Psychedelic mushrooms could be an appealing explanation.

“Psychedelic mushrooms appear advantageous for adaptation to new circumstances because they de-pattern the mind/brain, alter modes of perception and induce synaesthesia. [Some] argue that these mushrooms may have allowed our ancestors to forge connections between sounds, symbols and meanings, which is the essence of ‘the creative explosion’...” – Dr. Thomas Falk

So, how do magic mushrooms actually influence the mind? Like LSD, psilocybin binds to serotonin receptors in the brain and opens up new avenues of communication between parts of the brain that typically do not interact. Specifically, shrooms affect the brain’s prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain that is responsible for regulating thinking, interpreting thoughts, and controlling mood and perception.

People who take psilocybin often report synesthetic effects, like seeing sounds or hearing colors. Users sometimes report a feeling of closeness to nature or a feeling of oneness with the world around them. But the effects of psilocybin can last much, much longer than just the ten or twelve hours the drug stays in your system. People who use psilocybin sometimes report feeling heightened happiness and creativity for months or years after they’ve taken the drug.

Ketamine: From Party Drug to Therapy Tool

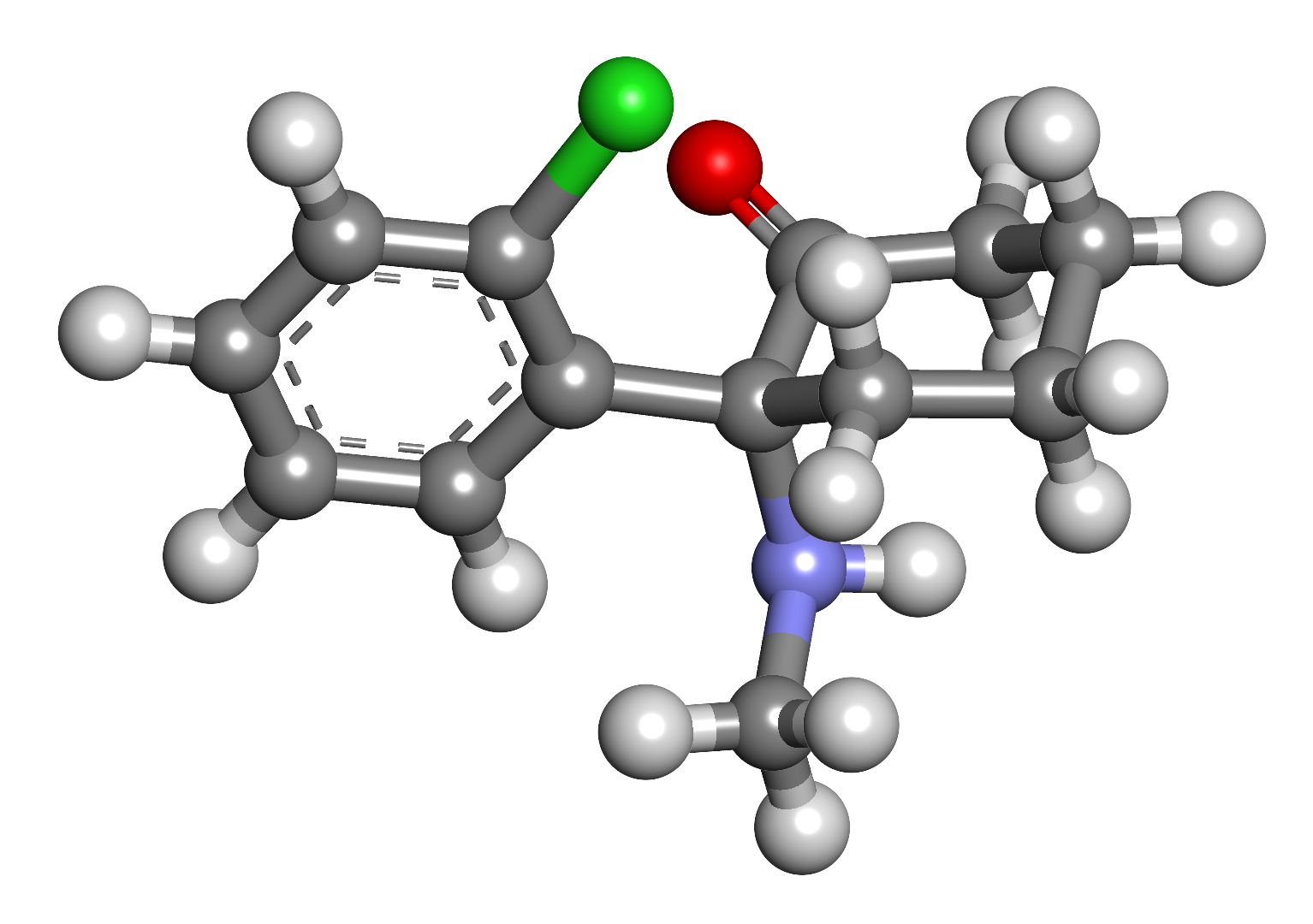

Ketamine is a drug that was first synthesized in the 1960s and was originally used as a battlefield anaesthetic. It became a popular club drug in the 1990s, and today ketamine therapy is gaining traction as a potential cure for depression and other mental illnesses.

Unlike the aforementioned drugs, which target serotonin, ketamine has a significant effect on glutamate, the brain’s primary chemical messenger. Glutamate influences how a person processes thoughts and emotions, and is also influential in memory and learning.

3D model of ketamine (Credit: Nerdking2015, via Wikimedia Commons)

It also produces and balances Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA), a neurotransmitter that calms and regulates emotions. High levels of GABA can lead to anxiety, while low levels can lead to depression. Low doses of ketamine can actually treat GABA imbalances by restoring glutamate levels to normal, which can stabilize and even “reset” the depressed brain. Particularly effective for people who struggle with suicidal thoughts, ketamine therapy has also become a popular potential treatment for a variety of mental illnesses.

Ketamine also affects the brain’s lateral habenula, the part of the brain that is responsible for processing difficult emotions and feelings. A 2017 study found that in depressed patients, the lateral habenula can “over-fire,” leading to a flood of negative feelings. Ketamine may actually also “reset” the lateral habenula to its healthy default state, easing symptoms of anxiety and depression. In 2019, the FDA approved a ketamine nasal spray for adults suffering from treatment-resistant depression.

In spite of all this, there are many risks to ketamine, which is addictive and has similar qualities to opiates. Ketamine can also cause high blood pressure, dizziness, bladder issues, and other effects, and currently it is only being prescribed for people with depression who have tried at least two other medications with no success.

The Spirit Molecule: DMT and Ayahuasca

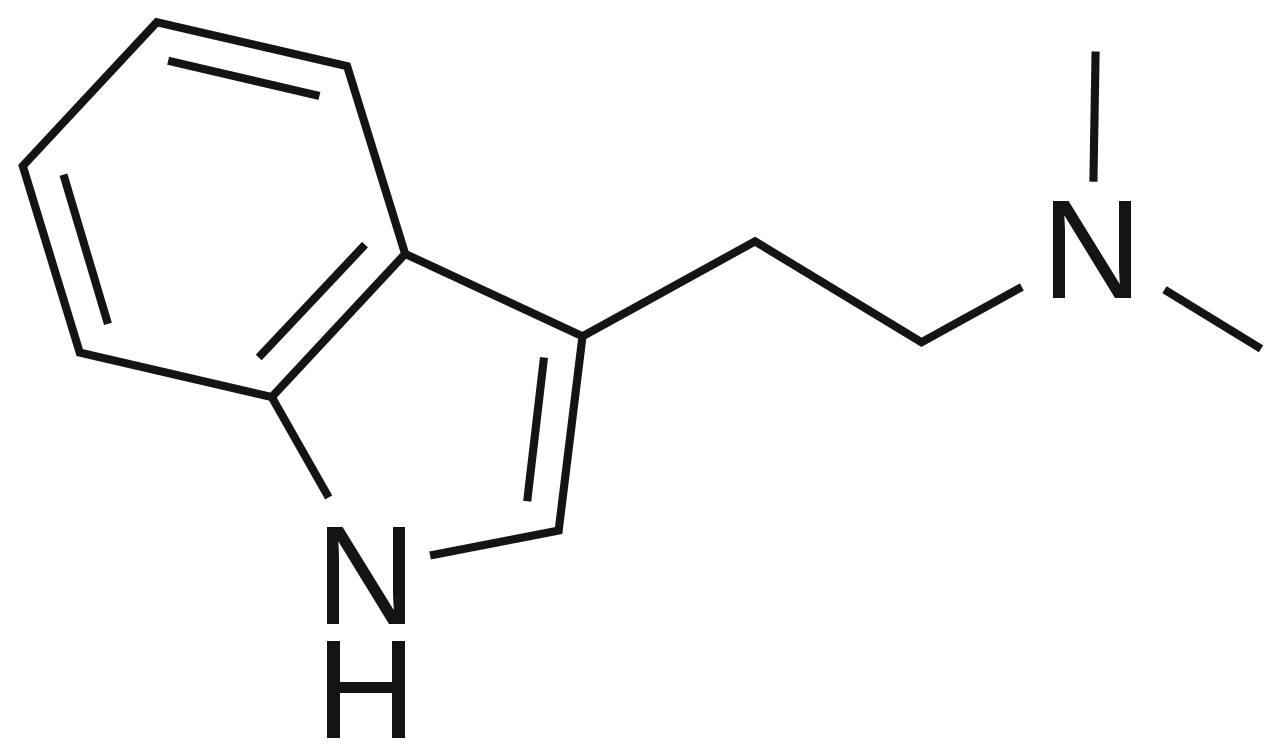

Another popular psychedelic is DMT, also known as N-dimethyltryptamine. Dubbed “the spirit molecule” by Dr. Rick Strassman, it is a hallucinogen with similar effects to LSD but is known for its extremely short-lived and sometimes highly unusual effects. DMT is found in some plants and can be made in a laboratory, and it has been used as medicine in some South American countries for centuries.

The effects of DMT vary, but some people report seeing bright flashing lights, while others report bizarre and sometimes terrifying hallucinations that occasionally include encounters with alien or spiritual beings, many of which apparently resemble “machine elves.”

2D structure of DMT (Credit: Harbin, via Wikimedia Commons)

Intriguingly, DMT actually appears in trace amounts in human blood and urine, leading some to believe that humans naturally produce it. This has produced a number of theories about DMT, some more scientifically verifiable than others. Some have proposed that DMT is naturally produced by the pineal gland, also known as the third eye; others have theorized that we produce the molecule during birth, death, and dreams. While none of these theories have been scientifically confirmed, it’s clear that there is a little DMT in all of us.

A 2018 study found that DMT’s effects on the mind resemble those experienced by people undergoing near death experiences, or NDEs. Both can invoke “the subjective feeling of transcending one’s body and entering an alternative realm, perceiving and communicating with sentient ‘entities’ and themes related to death and dying,” according to the study.

While DMT’s origins and purpose in the body are still largely a mystery, some studies have found that it results in a drop off of alpha waves and an increase in theta waves in the brain, a shift that resembles what happens when we dream.

Like the first two drugs we’ve discussed, DMT works by binding to a specific serotonin receptor in the brain, and most of its effects occur in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, which is an area related to mood, cognition, and perception. And also like the other drugs on this list, DMT has been found to have fast-acting antidepressant effects. It has also been identified as a potential treatment for addiction, reducing drug-craving and increasing introspection and coping skills.

Some indigenous tribes have been using DMT (in the form of ayahuasca, a much longer-lasting brew that includes DMT as its main ingredient) as part of healing ceremonies for centuries. Recently this tradition has become more popular around the world, with thousands flocking to the Amazon rainforest to partake in ayahuasca ceremonies.

One study found that ayahuasca leads to long-term increased connectivity in the brain’s salience network, which can affect how people process sensations. It also found that ayahuasca led to a decrease in connectivity in the brain’s default mode network (DMN), which can lead to a loss of one’s sense of self. Another study found that ayahuasca stimulated the growth of new brain cells in lab mice’s hippocampuses, a part of the brain that influences memory and cognition. The drug can also provoke a whole lot of self-reflection, which can trigger changes in one’s lifestyle.

Alternate Pathways: Dangers and Alternatives to Psychedelics

Of course, DMT and ayahuasca can produce just as many horrifying experiences as life-changing, rejuvenating ones. Research on these substances is still in its earliest stages, and none of this is to suggest people should attempt to treat themselves on their own with any of these drugs.

That said, the amazing therapeutic potential of these drugs can’t be overstated. When used with the proper intent and under appropriate supervision, they can change lives, open minds, and cure some of our trickiest mental blocks.

As we speed toward climate apocalypse, some have theorized that psychedelics could help lead to a deeper sense of empathy and connection that could trigger the last-minute changes we need. Others believe this optimistic view was disproved by the hippies in the 1960s and ’70s (“peace and love” didn’t exactly spring forth despite all the acid they dropped). But certainly, in a world where one in four people suffer from depression and everyone is fighting their own battles, real cures could be invaluable.

Now it’s up to us to decide how best to use the strange, mysterious drugs that flower among us, passing through our hospitals, and the nightclubs and alleyways behind them.

Ω

Title image: Brain Color A.I.-Generated by user vijaypal4171 from Pixabay.