Lise Meitner was an extraordinary physicist, one who broke through many of the strictures applied to women scientists of her time. Her career took her from her home in Vienna to Berlin, and then, once Hitler annexed Austria in 1938, to Sweden, where she spent the remainder of her career. She played an instrumental role in the discovery of nuclear fission, which quickly led to the creation of the atomic bomb. This was a scientific advance that Meitner always regarded with regret, as she never wanted her research to be used for destructive ends.

◊

The dais at the 1944 Nobel Prize award ceremony was packed – with men. And when the award for the prize in Chemistry was announced, one person stepped forward – a man, Otto Hahn. Only Hahn was on the stage that day to receive the award for the discovery of nuclear fission, despite the monumental contribution made by his partner in the research – a woman physicist named Lise Meitner.

Overlooking Meitner for her work with Hahn was something that, unfortunately, she had gotten used to over time. Not only was she working in a male-dominated field, she had also been a Jewish professor of physics in Nazi Germany until she was forced to flee. And, despite her research unlocking a key discovery that eventually led to the development of the atomic bomb, Lise Meitner was a pacifist.

Otta Hahn & Lise Meitner, 1912 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Regardless of her status as a woman scientist, she was recognized in some quarters for her work and her expertise. Albert Einstein was an admirer, and included mention of her in a letter he wrote to President Franklin Roosevelt encouraging the president to beat the Germans in the race for the A-Bomb. Roosevelt reached out to Meitner requesting her assistance, but Lise Meitner was adamant: “I will have nothing to do with a bomb,” she wrote.

She never reconsidered her opposition to the destructive uses of nuclear power, and she remained actively opposed to nuclear weapons for the remainder of her life. Much like J. Robert Oppenheimer, who did participate in the invention of the atom bomb – and even to an extent Albert Einstein, whose theories facilitated its creation – she was afflicted with guilt for the role she and her colleagues played in its development and ultimate deployment at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Lise Meitner: Physics Prodigy

Meitner's indirect participation in the research that led to the creation of the atomic bomb positively drips with irony. How did she become so closely associated with nuclear weaponry, while personally finding warfare and its weapons abhorrent? A look back at Meitner’s development as a scientist in her native Austria and her first adopted home of Berlin may prove instructive.

Meitner was born in 1878 to a middle-class Jewish family in Vienna, just at the time when Vienna was an emerging capital of culture, science, and the arts. Her father was a hard-working man of his time, one of the first Jewish attorneys in Austria. He had a vision for his family, and he pushed all his children to achieve success both educationally and professionally.

Lise was precocious from the start, and was inspired to study in the sciences by two-time Nobel Prize winner Marie Curie, whose experiments with radioactivity were well known throughout Europe. Curie faced discrimination due to her sex; yet she was able to break through many barriers due to her accomplishments and the sheer force of her intellect.

Meitner Overcomes Hurdles to Academic and Scientific Achievement

The young Meitner also faced obstacles to her progress. For example, once she completed her primary education, she was expected to end her academic pursuits. In Vienna as late as 1900, women were not allowed access to higher education. But with the help of her father, and the family’s wealth, all the children of the Meitner family, male and female, were afforded a good education.

Over the course of her career, Lise Meitner became aware of the work of Albert Einstein, and he of hers. Because of her work with uranium, Einstein playfully called her the “German Marie Curie,” a sobriquet that stuck despite her not being German. And Meitner used Einstein’s famous E=mc2 equation to jump-start her research into nuclear fission.

Since girls could not attend college or graduate school, the family paid for private tutors that would qualify them for advanced degrees. Lise benefited greatly from this exposure to academic study. In 1905, she became the first woman to receive a doctoral degree in physics at the University of Vienna.

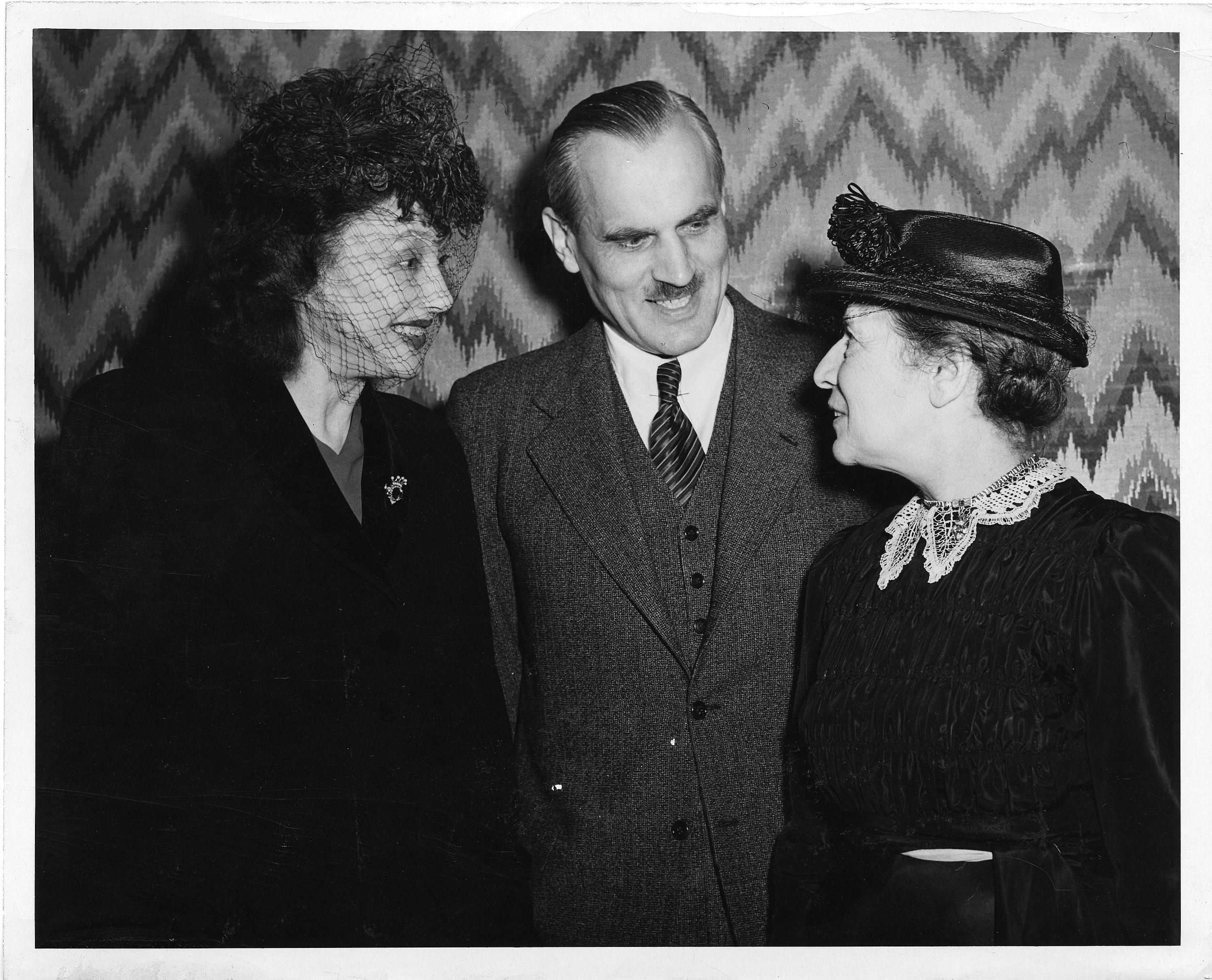

Lise Meitner (right) with actress Katherine Cornell and physicist Arthur H. Compton, National Council of Christians and Jews award ceremony, 1946 (Source: Smithsonian Institution, via Wikimedia Commons)

Despite this remarkable achievement, there were very few opportunities for Meitner to advance in a career. Although Vienna was the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, it was not cosmopolitan enough at the time to offer women academic or research fellowships. She soon realized that she would have to relocate to a larger, more advanced city to accomplish her professional and scientific goals.

Things were better in Berlin in the early years of the 20th century, but not ideal. Her work, including a 1907 paper she published on the “nuclear atom,” got the attention of the renowned physicist, Max Planck, and he extended an invitation to study with him at the Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin. Despite his reluctance to work with women, her intelligence got his attention, and within a year he had asked her to join his scientific staff as an (unpaid) assistant.

Men Took Credit for Meitner’s Accomplishments

In 1922, while working independently on the effects of electron emissions on atoms, Meitner became the first scientist to describe electron behavior that resulted in the release of energy. One year later, as part of his Ph.D. research, French physicist Pierre Auger separately described the same physical process. Despite Auger being the second scientist to publish these results, it was his name that became associated with the “Auger effect.” Meitner’s contribution was overlooked.

Meitner may have succeeded in facing down sex discrimination, earning respect for her diligence, but money didn’t follow. In fact, she worked without a salary until the age of 35, when she was made a full professor at Friedrich Wilhelm University.

Nevertheless, she persisted. In 1926, she became the first woman in Germany to be named as a full professor at the same Berlin university where her mentor Max Planck taught. Her research into the behavior of atoms, particularly in the “heavy metals” (radioactive elements such as uranium), brought her into a research partnership with chemist Otto Hahn. Together they would go on to make the monumental discovery of nuclear fission, the process by which a metal such as uranium when bombarded by neutrons would release massive amounts of energy.

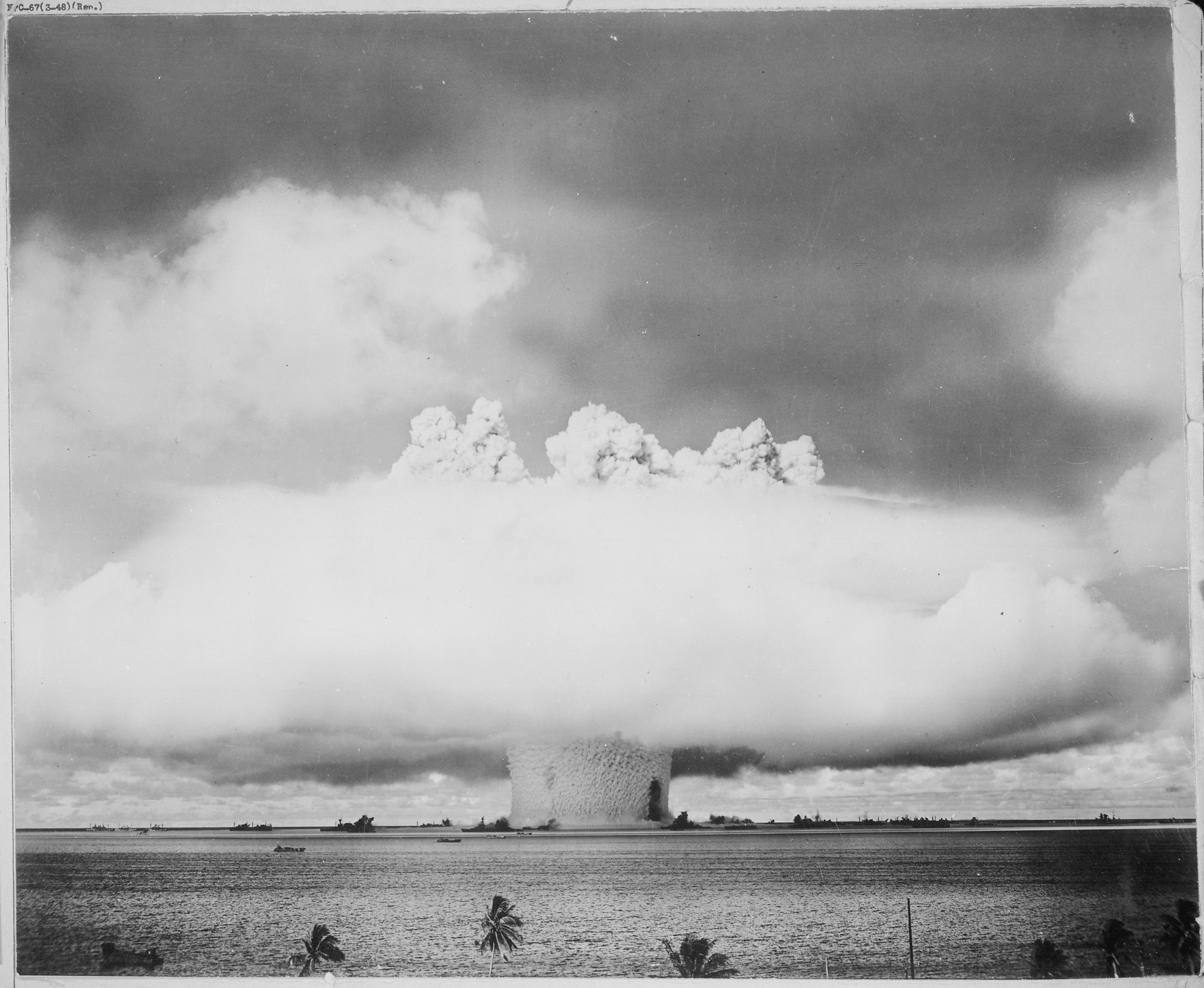

Atomic bomb test, Bikini Atoll, July 25, 1946 (Credit: U.S. National Archives, via Wikimedia Commons)

Hahn and Meitner were interested in the possibility of creating even heavier metals by bombarding these elements with neutrons. However, the result of their preliminary investigations showed that the resulting elements were lighter, not heavier. This was a conundrum: How could a “heavy” atom become lighter after adding a neutron?

Meitner had a flash of insight – what if the application of neutrons to uranium caused the uranium atom to break apart rather than fuse with the neutron? If that were the case, she theorized, then what they were witnessing was a new condition, which she named “fission,” meaning that the atom split and would then release energy as a result.

Even after beginning her collaboration with chemist Otto Hahn she still faced discrimination. In her time in Berlin, she was never allowed entry into Professor Hahn’s all-male lab space. She toiled in a makeshift basement carpentry workshop with its own entrance.

Hahn confirmed her theory, and Meitner later wrote that this discovery, nuclear fission, “opened up a new era in human history.” This history was to be darker than Meitner imagined.

Meitner Resists the Blinding Light of Atomic Weapons

It’s not possible to discuss Lise Meitner and her work without contextualizing it within its time period – the 1930s and ’40s. Meitner was a Jew working in a prominent position at a university in Berlin. As an Austrian citizen, she was somewhat protected when Hitler rose to power in 1933 and began his series of purges of Jews and other “undesirables” in German society.

Even after her nephew, Otto Frisch, who also worked at the university, was forced to resign, Meitner did not stop working or seek to protect her academic position. She apparently suffered from a delusion shared by many prominent Jews in the early days of Nazi control that the value of her work would save her.

For a deeper examination of her life in Hitler’s Germany, and its aftermath, watch the documentary Lise Meitner: The Mother of the Atom Bomb on MagellanTV.

It did not. In 1938, her position as an Austrian Jew working in Germany became tenuous once Hitler annexed her home nation. Finally comprehending the crisis she faced, Meitner fled her adopted home surreptitiously, leaving with little money and virtually no possessions, and eventually resettled in Sweden, where she was able to continue to consult with Otto Hahn, who stayed in Germany.

Their work on nuclear fission caught the attention of Albert Einstein, who immediately saw its import and strategic value for whoever could first harness the power of the atom. As a Jew who had escaped to the United States, Einstein’s primary concern was to beat the Germans in what he imagined would be a race to weaponize Hahn and Meitner’s discovery.

Meitner wrote of her “sorrow and despair” at the wartime application of her scientific research. Not so with Einstein, who wanted to participate in the development of a weapon. He was rejected, however; despite his prominence, he couldn’t obtain a security clearance.

He wrote of his concerns to President Roosevelt, who understood the potential consequences and agreed to fund research into the development and eventual deployment of the atomic bomb. This top-secret plan was named the Manhattan Project.

Meitner Is Overlooked by the Nobel Prize Committee

Hahn, Meitner’s research partner, published his findings on nuclear fission in Germany in 1942. Meitner was not mentioned in the paper. It’s widely believed that her role was omitted from Hahn’s publication because Hahn couldn’t risk the possible repercussions from having a Jew’s name on this piece of research. Others see it as merely one more example of sex discrimination in academia. Probably it was both.

This erasure continued when the Nobel Prize committee awarded its 1944 Prize in Chemistry solely to Otto Hahn, “for his discovery of the fission of heavy nuclei.” Despite calls for the Nobel Prize committee to reconsider its oversight after the war had ended, Meitner’s contribution was never acknowledged by the Nobel committee – nor by Otto Hahn himself. Nonetheless, throughout the remainder of her life, she never spoke in less than admiring terms about her research partner.

Physicist Otto Stern and Lise Meitner, c. 1937 (Source: Wikipedia)

Meitner was, however, especially critical of fellow scientists who collaborated with the Nazis during the war. Speaking after the war about noted German theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg, and referencing Nazi-run concentration camps, she said, “Heisenberg and many millions with him should be forced to see these camps and the martyred people.”

Lise Meitner and the Legacies of Overlooked Women Scientists

Despite her unfortunate moniker “mother of the atom bomb,” Meitner can fairly be said to have played a key role in introducing the era of atomic power to the world. Her work was certainly ground-breaking, and it can’t be underestimated. Had she been able to continue working in Germany without having to flee for her life, her reputation and the accolades she received might have been dramatically different.

As it stands, however, Meitner represents the powerful determination of a woman whose scientific interests and achievements could not be silenced or held back due to her position as a woman in a misogynistic society. In this regard, her reputation stands firmly alongside other women in the sciences who did not let discrimination hold them back from seeking, and accomplishing, great things.

Lise Meitner’s experience has echoes in the careers of other women scientists in the 19th and 20th centuries. For example, astronomer Annie Jump Cannon was plucked from classes at Radcliffe College to become an unpaid assistant to renowned astrophysicist Edward Pickering at the Harvard Observatory, much as Meitner was taken under the wing of Max Planck only 30 years later.

And Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who co-discovered the first radio pulsar (a type of rapidly spinning neutron star) in 1967, was overlooked for the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physics that recognized the discovery; the prize was awarded to male colleagues (Antony Hewish and Martin Ryle, under whom she was a post-graduate researcher at the University of Cambridge at the time) much as Otto Hahn alone received the Nobel for work he did jointly with Meitner.

Lise Meitner was a conflicted scientist, one who was aware of her work’s importance and yet was not blind to the moral and ethical consequences of the application of pure science to the pursuit of bigger and more destructive weaponry. When she died, her nephew Otto Frisch made specific instructions for the epitaph on her headstone. It reads simply, “Lise Meitner, 1878–1968 – A physicist who never lost her humanity.”

Ω

Kevin Martin is Senior Writer for MagellanTV. He writes on a wide variety of topics, including outer space, the fine arts, and modern history. He has had a long career as a journalist and communications specialist with both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. He resides in Glendale, California.

Title Image source: Wikimedia Commons