Long before the era of televised trials, a 1920s murder case gripped the nation.

◊

On January 24, 1995, viewers worldwide were glued to their screens awaiting the verdict in the O.J. Simpson trial. Between the notoriety of the defendant and the trial’s ubiquitousness on home televisions worldwide, the case was unparalleled in the sway it held over the American public. But decades before Simpson was found not guilty for the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman, another notorious case enthralled the populace.

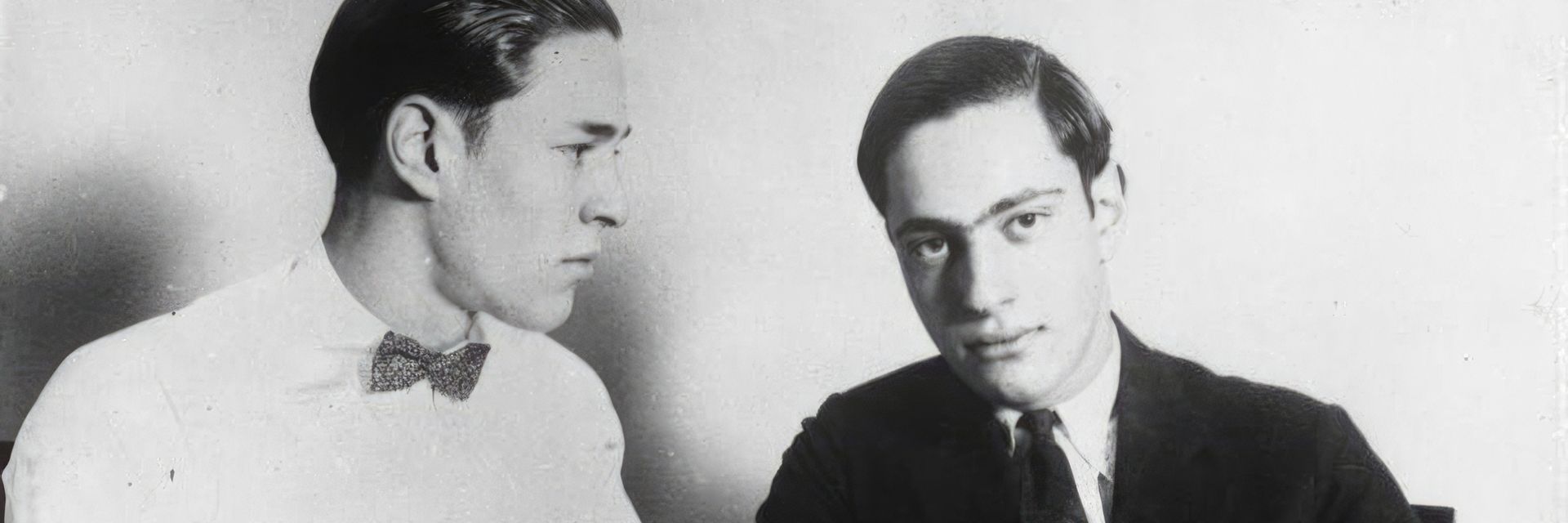

In 1924, 19-year-old Richard Albert Loeb and 18-year-old Nathan Freudenthal Leopold were two wealthy, intelligent college students who seemingly had their privileged lives on track. Both were raised in the moneyed Kenwood neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side but, while they casually knew one another as children, it wasn’t until they both enrolled at the University of Chicago that they formed an unbreakable, if decidedly troubled, bond.

For more about the most notorious homicides in modern history, watch MagellanTV's Murder Maps.

Although the men shared a Jewish heritage, on the surface they were quite different. Richard, the son of a retired Sears Roebuck vice president, was outwardly charming, social, and attentive to his looks. Nathan, the child of a wealthy box manufacturer, was smaller in stature and awkward, with a brooding nature. While Richard studied history and indulged in reading detective stories, Nathan was a skilled linguist and ornithologist; he was particularly interested in the parasitic nesting strategies of brown-headed cowbirds. Nathan was also preoccupied with philosopher Friedrich Nietsche, particularly his concept of the Übermensch (“Overman” or “Superman”).

Nietsche advocated for shedding restrictive and outmoded systems of belief, but he warned against acts of immorality masquerading as self-actualization.

An intense friendship soon turned into a sexual relationship fraught with jealousy and dysfunction. It seemed Richard and Nathan both yearned for and despised one another, with Nathan being the one more driven by sexual desire; Richard acquiesced. During one especially testy argument, Nathan suggested they settle it via poker – the loser, he declared, would commit suicide. When Richard refused, Nathan threatened to kill him.

In addition to these volatile dynamics of their relationship, the men shared a mutual affection for vandalism, theft, and arson. Together, they set fires to abandoned buildings and robbed fraternities. But these lesser crimes shortly evolved into fantasies of violence that the pair would put into terrible action.

The Murder of Bobby Franks

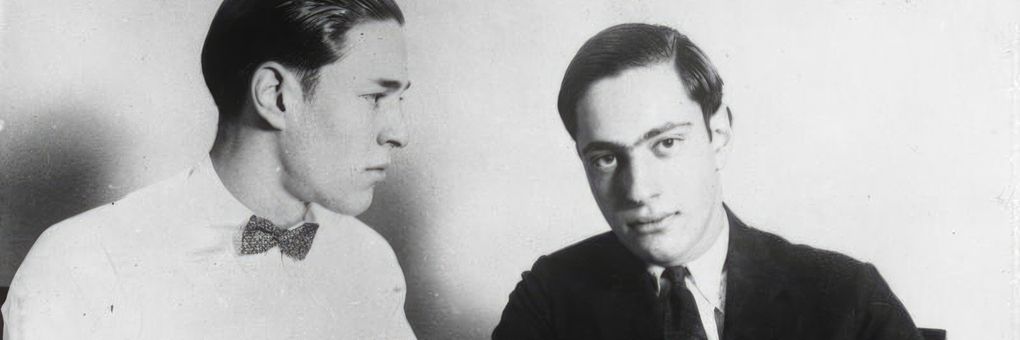

On May 21, 1924, Richard and Nathan kidnapped Richard’s second cousin, 14-year-old Bobby Franks, as he was walking home from a baseball game. In the back of their rented car, they beat Franks with a chisel and suffocated him by putting tape over his mouth. They then drove 25 miles to Hammond, Indiana, where they dumped his body in a marshy culvert and splashed hydrochloric acid on Franks’s face and genitals to obscure his identity. To throw off law enforcement, they staged a ransom plot, with Nathan posing as a kidnapper, calling Bobby’s mother, and mailing a ransom letter to the family. The plan was foiled, however, when the victim’s body was discovered.

Bobby Franks (Source: Wikemedia Commons)

In their attempts to find the perpetrators, investigators studied the ransom note, determining that it was written by someone with a “more than ordinary education.” Analysts were also able to trace the type to a specific typewriter. The most significant clue, however, lay beside Franks’s body: a pair of glasses with a distinctive hinge manufactured by a Brooklyn-based company. The glasses were then traced to three potential wearers, one being Nathan; he was taken in for questioning by State’s Attorney Robert Crowe.

The ransom note (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

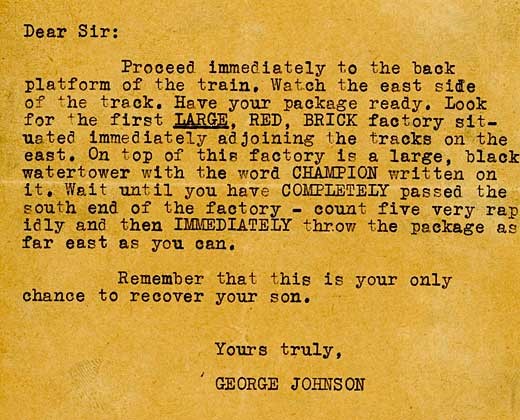

Nathan’s alibi was shaky. He claimed that he and Richard had been drinking and seeking the company of women. Crowe’s suspicions rose after discovering letters in Richard’s bedroom that Nathan had written to Richard. One letter pointed to the young men’s sexual relationship, which raised doubts about the claim that they were picking up girls at the time of Franks’s murder. Believing Richard to be the weaker-minded of the two, Crowe interrogated him. Richard confessed to the murder on May 31, and Nathan did so shortly after.

Some historians have suggested that Leopold and Loeb committed additional murders, but these claims have not been proven.

Transcripts of the Leopold and Loeb confessions reveal striking indifference to their victim. In fact, while the crime was premeditated and plotted, the victim they chose to kill was almost an afterthought. Franks simply happened to be a convenient target. According to Richard, while he first felt regretful, “then the excitement, the accounts in the paper, the fact that we had gotten away with it and that they did not suspect us, that it was given so much publicity and all that sort of thing, naturally went to the question of not feeling as much remorse as otherwise I think I would have.” For Nathan’s part, he admitted that he was drawn to the “thrill, the experience” and the chance to attempt to outsmart the police.

Upon their arrest, newspapers splashed their front pages with details of the crime. Articles begged the question: How could two seemingly respectable, upstanding young men be responsible for such a senseless act? The Chicago Daily Journal coined the phrase “dementia jazzmania,” to describe what they deemed to be the amoral, hedonistic lifestyle that led the men to kill. Speculation on the intimate relationship between the men fed the salaciousness of the crime, while their Jewish heritage and wealth also became fodder for antisemitism.

A Senseless Crime?

The men had had every opportunity handed to them, but no life story is without its chapters of darkness.

The murderers (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In Nothing but the Night: Leopold & Loeb and the Truth Behind the Murder That Rocked 1920s America, Greg King and Penny Wilson write that Richard’s parents were aloof and detached, his governess domineering and punitive. Richard largely abided by the rules of his household, while seeking refuge through stories and excitement via the occasional theft. Once he enrolled in college at 14, the freedom was likely intoxicating. He emulated the actions of older boys, including drinking and trolling for girls. Nevertheless, his interest in sex itself was minimal. “I could get along easily without it,” he later stated.

Nathan, though, experienced sexual abuse at the hands of his governess. While she was dismissed once her actions came to light, it’s unlikely the matter was openly discussed and may have been a source of shame for Nathan. In an era in which homosexuality was classified as a mental illness, Nathan also likely felt the burden of concealing his attraction to boys.

Still, these emotional and psychological challenges could not excuse Nathan’s early problematic behaviors, including animal cruelty: Those same birds he studied were often first dispatched by his gun. And, after a sexual encounter with another boy, he discovered an interest in inflicting pain, effectively conflating sexual gratification with violence.

In essence, before forging their relationship, both men harbored internal conflicts, had experienced neglect and mistreatment, and were drawn toward thrill-seeking behaviors. Their magnetic attachment to one another was perhaps less parasitic in nature – with one man manipulating and dictating the actions of the other – and instead more comfortably symbiotic.

Darrow Defends Leopold and Loeb at Trial

Richard and Nathan’s parents spared no expense when it came to their defense team. They hired Benjamin Bachrach and Clarence Darrow, who would go on to serve as the defense attorney for high school teacher John T. Scopes during the Scopes Monkey Trial. Darrow convinced Richard and Nathan to enter a guilty plea. His goal was to spare them the death penalty and felt a bench trial overseen by judge John R. Caverly would benefit his clients.

Clarence Darrow (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

While there was no jury, members of the public attended the proceedings, with hundreds spilling into the corridors of the courthouse. Though the majority of the invested public advocated for a harsh penalty, others were more ambivalent. In a phenomenon far from unfamiliar in notorious criminal trials, Richard was often the focus of female admiration. In Nothing but the Night, the authors explore the “almost romantic portraits of Richard in jail,” and share quotes from infatuated women who savored Richard’s supposed “lambent eyes and tender chin. … His gentle and disarming way and moist, soft-looking lips.” Nathan was not paid the same attention.

Teams of psychologists testified both for the defense and prosecution, with the defense arguing for diminished capacity based on a host of factors including the men’s childhood neglect, their obsessional tendencies, and even dysfunctional endocrine glands. Defense psychiatrist William White addressed the toxic relationship between the defendants: “Richard needed Nathan’s applause and admiration in order to confirm his sense of his own self. But Nathan also needed Richard to play a role; Richard took the role of a king who was simultaneously superior and inferior. … Nathan would never on his own initiative have murdered Bobby Franks. … And I don’t believe Dickie would have ever functioned to this extent all by himself.”

Meanwhile, the prosecution portrayed the men as villainous perverts. The death penalty, they suggested, was the only reasonable response to such a heartless and horrific crime.

During closing arguments that lasted 12 hours, Darrow claimed the defendants were not fully responsible for their actions. “Nature is strong and she is pitiless. She works in mysterious ways, and we are her victims,” Darrow said. “We are only impotent pieces in the game He plays upon this checkerboard of nights and days. … What had this boy had [sic] to do with it? He was not his own father; he was not his own mother. … All of this was handed to him. He did not surround himself with governesses and wealth. He did not make himself. And yet he is to be compelled to pay.”

Perhaps presaging the “affluenza defense” asserted in a more recent case, the argument angered many. If young men could be excused for their behaviors because of their fortunate life experiences, could the same not be argued for the indigent and unfortunate? However, Darrow’s closing arguments were also praised as a moving indictment of capital punishment.

Robert Crowe had ample opportunity to scorn and repudiate the pair. He said, “I wonder now, Nathan, whether you think there is a God or not … whether you think it is pure accident that this disciple of Nietzsche’s philosophy dropped his glasses or whether it was an act of Divine Providence to visit upon your miserable carcasses the wrath of God.”

Together Until the End

Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold were both sentenced to life imprisonment plus 99 years. Surprisingly, the men spent much of their time housed in the same facility. Nathan said of their interactions, “[we were] as close as it is possible for two men to be. Whatever happened to our individual assignments, we worked together as a team … we made it an invariable practice to have a twenty-minute talk immediately after breakfast each day.”

Nathan Leopold in his cell (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

n 1936, however, Richard’s incarceration came to an end; he was killed in a prison fight with another inmate. Nathan was at Richard’s bedside for his final breaths. Though there was speculation that Nathan had a hand in his murder, there is little evidence to support this claim. In fact, Nathan would later say, “I felt like half of me was dead.”

Incidentally, Nathan also took advantage of Richard’s demise to tell his side of the story, insisting in an autobiography that Richard had been the instigator of Franks’s murder and that he had been under Richard’s bewitching command.

In 1958, after serving 34 years in prison, Nathan was released on parole. He migrated to Puerto Rico, where he married a widowed florist, taught mathematics, and worked as an X-ray technician. He continued to study birds until his death in 1971.

A True Crime Legacy Endures

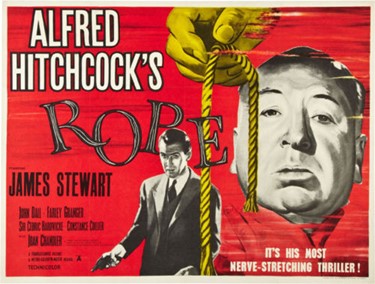

Poster for Hitchcock’s film Rope (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In the 1920s, few trials seized the public’s attention like the Leopold and Loeb case. Beyond the shocking circumstances of the crime, the defendants’ personal characteristics and backgrounds also seemingly went on trial through the media.

The case has had enormous staying power, inspiring numerous works of fiction. They include Meyer Levin’s Compulsion (1924); Patrick Hamilton’s 1929 play Rope, which was subsequently adapted for film by Alfred Hitchcock; and the 2002 film Murder by Numbers. The men also became the unlikely subjects of a 2005 musical, Thrill Me: The Leopold and Loeb Story.

A horrific case of human depravity. A cautionary tale of intellectualism and privilege without conscience. Or, perhaps, one of the strangest love stories ever told. However the Leopold and Loeb case is characterized through our modern lens, it serves as a reminder of how the insatiable appetite for true crime stories was with us long before the era of televised trials.

Ω

Matia Query is a freelance writer and the editor of BookLife, the indie author wing of Publishers Weekly. She lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.

Title Image source: Wikimedia Commons